Beware of Greeks telling tales

Following the evidence can unravel conventional claims.

I have loved reading history since I was very young.

One bit of ancient history never made much sense to me. It was the sequence that said “there were these Scythians who conquered Media and then there was this Median Empire which suddenly appeared and the Medians overthrew the Assyrians and then Cyrus overthrew that Empire and founded the Persian Empire, which we call the Achaemenid Empire even though the first Achaemenid Great King/King of Kings was Darius, not Cyrus nor his son Cambyses.”

This dizzying cascade of Empires which spring up and are replaced is not how Imperial sequences normally work. Ever since I first came across it, it just seemed a bit puzzling to me.

Well, it turns out I was right to be puzzled because this cascade of Empires coming and going is not supported by the available evidence. Provided the evidence includes rather more than tales told by Greeks.

The historical sequence outlined in Christopher Beckwith’s typically excellent compiling of evidence and scholarship The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China is quite different. There was only one Empire, which was founded by the Scythian conquest of Media and places eastward around 650BC.

A generation after the Scythians created this empire, a local ruler of mixed Scythian royal clan and Median lineage, Cyaxares, seized control. His lineage ruled for a couple of generations and then a local ruler of mixed Scythian royal clan and Elamite lineage, Cyrus, revolted and seized the empire. Like Cyaxares, he did not found any Empire, he seized control of the existing one.

His lineage (which was not Persian, though Cyrus was retrospectively “Persianized” by Darius) ruled for two generations. Both he and his son Cambyses conquered lands westwards (hence impressing the Greeks). When Cyrus tried his hand against steppe Scythians, he was defeated and killed.

After Cambyses died without male heirs, his cousin Darius, of mixed Scythian royal clan and Persian lineage, seized the throne, establishing the Achaemenid dynasty. It was an empire of Medes and Persians, as the Medians (really Scytho-Medes) continued to dominate the administration even as the Persian language became the imperial language and Persian spearmen and foot archers dominated the military forces.

There is no dizzying array of Empires rising and being replaced. There is just the one Empire, ruled by a sequence of dynasties whose common element was descent from the Scythian royal clan. A royal clan known variously as arya, ariya, aria, harya (a later version of which is aryan).

The wars that brought Cyrus and later Darius to imperial power were civil wars within an existing empire. They were very different from the outsider conquest by Alexander the Great which did actually overthrow that Empire and replaced it with a new (albeit very short-lived) one.

Trade and Empire

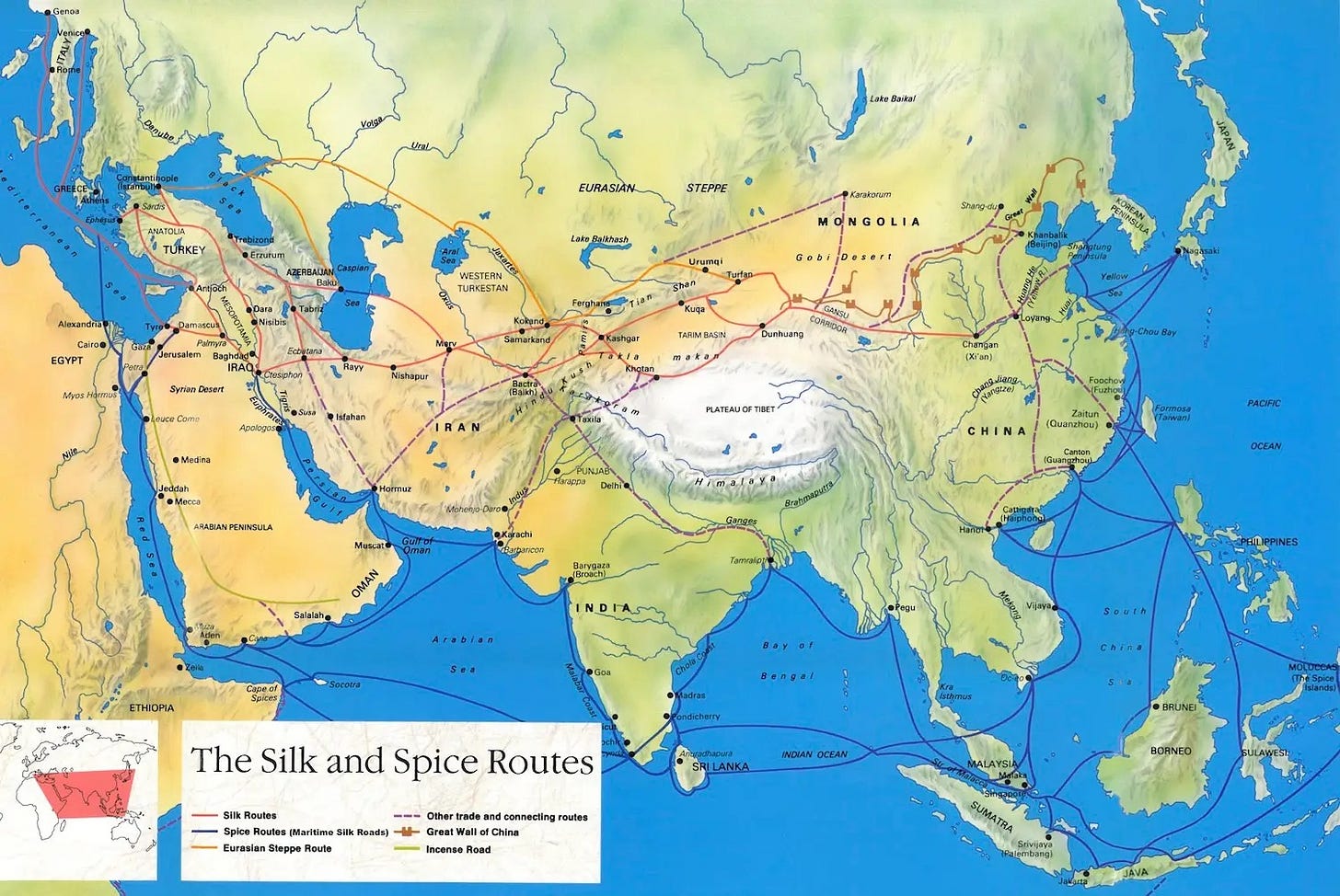

This Scytho-Median-Elamite-Persian empire, that came to be ruled by the Achaemenid dynasty over a century after its founding, is the first (farming) mega-empire (pdf). This makes sense, for what you need to have large empires is lots of trade, pastoralists tend to encourage trade (either on their own behalf, or as revenue source) and the steppes (relatively easy to traverse compared to mountain ranges and deserts) were key trade-routes for centuries.

So, having the steppes unified by the Scythians generates the trade that leads to the first farming mega-empire.

The reason why you need lots of trade to have large empires is that administrative costs have negative returns to scale (they increase faster than does territory) while income from land tends to scale up linearly (twice as much land of a given quality returns twice as much revenue). If you are just relying on revenue from land, you will have lots of small jurisdictions, as rising administrative costs will inhibit territorial expansion.

Trade revenue, on the other hand, can generate increasing returns-to-scale over various territorial ranges. This is particularly so if the ruling authority provides public goods that increase trade, such as protected trade-routes and market places. Part of the way this increases revenue is by increasing the productivity of land through increased specialisation.

We can see the increased-trade-leads-to-larger-jurisdictions effect in the application of steam power to transport in steamships and railways from the 1820s onwards. The dramatic fall in transport costs leads to rising trade and to an era of (European) imperial expansion in Africa and Asia. Especially as the telegraph reduced communication costs (and so administrative costs).

Whenever China was unified, there was a surge of trade and of empire-building across Eurasia, as China importing horses (due to a lack of selenium in the soil of the Chinese heartland) made it a central generator of trade. A unified China was a more prosperous China that bought more horses and exported more silk, porcelain and other trade goods.

Whenever Chinese unification collapses, so do empires across Eurasia. China’s (internal) processes of unification and dissolution generates the rise-and-decline of empires across Eurasia.

For example, the Crisis of the Third Century, which the Roman crisis is only part of, follows the collapse of the Han dynasty. The wider Eurasian crises includes a wave of imperial collapses, overthrows (the Persian House of Sassan overthrows the Parthian Arsacid Dynasty) and declines (the Kushan Empire fades away). Rome only survived as it had the trade revenue of the Mediterranean.

Over 13 centuries earlier, New Kingdom Egypt managed to fight off the Sea Peoples in a series of victories by Ramseses III but still collapsed within a few decades as having most of their trading partners being wiped out in the Bronze Age collapse destroyed the trade revenue “cream” that the New Kingdom had come to rely on. The first recorded labour strike being the workers on Ramseses III tomb downing tools because they had not been paid.

The Qin-Han unification of China led to a situation where you could go from the Atlantic coast to the East China Sea and pass through four imperial jurisdictions* (Rome, Parthia, Kushan Empire, Han China). The Sui-Tang unification of China led to a situation where you could go from the Atlantic coast to the East China Sea and pass through two imperial jurisdictions* (the Abbasid Caliphate and Tang China). The rise of the Ottoman Empire was facilitated by the Yuan-Ming-Qing unifications of China.

The decay of the Tang Dynasty with the An Lushan (755-63) rebellion coincides with the Abbasid Caliphate beginning to shed territory. The revenue importance of trade with Tang China probably explains why the Abbasid caliphate, having fought (and won) the Battle of Talas (751) against Tang China, later sent cavalry to help the Tang suppress the rebellion.

Chariots to lancers

Why would the Scytho-Median-Elamite-Persian Empire based on the Iranian plateau be the first (farming) mega-empire? Be the first trade expansion that enables a mega-empire? Because the Scythians invented the composite recurve bow (or, at least, first perfected its military use).

The first systematic use of horses in warfare is via chariots, which were also invented on the steppes around 1950BC. An archer or spearman on a chariot can carry more arrows or spears, and shoot or throw further, than can someone on horseback. Hence, despite being more complex than riding a horse, less manoeuvrable and a little more terrain-restricted, chariots spread across Eurasia, dominating warfare.

The composite recurve bow changes that. Suddenly, there is a horseback weapon that can rival the range and power of an archer on a chariot. Riding a horse is simpler, more manoeuvrable and a little less terrain-restricted than a chariot. The development of horse archers, and then the development of the response to the horse archer, the mounted, armoured lancer, dooms chariots.

Effective use of horse archers requires numbers and coordination. Once horse-archer warfare is developed, it becomes possible to unify much (or even all) the steppes under a single rulership.

The Scythians are the first to develop such warfare and the first to unify the steppes. A unified steppes means more trade. More trade enables the first mega-empire in farming lands.

Franchised rulership

The Scythians were not a literate culture and while they did have a few cities on the fringes of the steppes, they were ruling a territorially vast domain where (mobile) herds were the main productive asset. They had an urgent need to minimise administrative costs.

Beckwith argues that the Scythians invented feudalism. Feudalism is a term medievalists have become wary of because it has come to mean many different things. It makes most sense as a term if we think of feudalism as a systematic structure of vassalage and fiefs.

If we think of it in that way, and if we consider the urgent need of any Scythian polity to minimise administrative costs, then it absolutely makes sense that they invented feudalism: that is, invented rulership as a systematic system of vassalage and (in farming lands) fiefs.

For both vassalage and fiefs are ways of minimising administrative costs. Rather than having some bureaucratic structure relying on a constant stream of information and orders, you have a structured relationship with a vassal, or a fief-holder, with a clear set of mutual obligations and expectations. Nor do you have to collect revenue and then dole it out again. The vassal and the fief holder do that directly themselves.

In both cases, it is a relationship that can be structured by a contract. Especially a contract sworn by an oath, oaths being typically key features of non-literate, or low-literacy, cultures.

You don’t get a choice in who to swear allegiance to (vassal), nor service to (fief). You don’t get a choice in the terms of the vassalage or the service. But you do have an explicit or implicit contract that you swear to uphold.

The most explicit version of contractual allegiance I am aware of is the oath of allegiance of the Kingdom of Aragon:

We, who are as good as you, swear to you, who are no better than we, to accept you as our king ... provided you observe all our liberties and laws; but if not, not.

What sort of contract gives you no choice of partner nor of contents but is still a contract? A franchise contract. If you are a McDonalds franchise, you cannot become a Pizza Hut or a Hungry Jacks or a Burger King. You do not have any say in the terms of the contract. But the franchise is still based on a contract.

Thus, vassalage is franchised (sub)rulership. A fief is a mounted-warrior franchise.

Fiefs were compatible with almost any property system. From freehold, where it is a form of tax-in-kind-via-service, to your landholding being completely conditional on the service, as in Russian dvorianstvo service nobility.

Fiefs did not need to involve any land ownership at all. The tax-fiefs of Islam (iqta, timar, jagirs, tuyuls) and of the Palaiologoi medieval Roman state (pronoia) gave tax collection rights in return for (typically) military service.

Despite claims to the contrary, they were not land grants in the landowning property sense. In the case of Islam, making fiefs landed property would make them subject to Sharia inheritance laws. Sharia requires property to be divided (albeit unequally) among all a father’s children.

The point of fiefs, of the mounted-warrior franchise, was to provide enough income to support at least one mounted (usually armoured) warrior. Making them land ownership grants subject to Sharia inheritance rules would lead them to becoming too small to support a mounted warrior within a single generation.

There were (sub)rulership franchises (vassals) and warrior franchises (fiefs) for exactly the same reason we have franchises now. Vassalage and fiefs both economise on administrative costs, clearly structure the interaction and allocate liability and risks in a clear way.

Beckwith argues the Scythians also invented feudalism in the sense of fiefs by conquering the little Median city-states and allocating land to support and provide horse archers.

I had thought the first state to systematically have mounted-warrior fiefs was the Parthian Empire from C3rd BC onwards. But I had wondered about the Achaemenid Persians.

Vassalage is older than the Scythians. When any imperial ruler forced conquered rulers into being tributaries, that was clearly a form of vassalage. But it was also a way you dominated peripheral regions rather than how you administered the core of your empire.

The Scythians do seem to be the first to make vassalage the systematic basis of ruling. Which makes complete sense for the first steppe empire, when you consider why franchising (sub)rulership makes sense: it greatly economises on administrative costs.

There were also precursors to allocating land to support troops. The Mesopotamian rulerships had “spearman land”, “archer land” etc. But such were much more land-grant militia systems.

What the Scythians appear to have done in conquering Media and other farming lands is to grant the first genuine fiefs. That is, allocated land-with-farmers whose service supported one or more mounted warriors. Which again makes sense, both to minimise administrative costs and because it did not require the fief-holder to do, or have knowledge of, farming. Which the pastoralist Scythians would generally not have had.

The problem with militia systems is that the need to farm restricts the time the soldier can spend training or away from the land and undermines the incentive to invest in training and equipment. For these reasons, militia systems tend to degenerate over time.

A genuine fief does not require the fief-holder to spend any time farming, or supervising farming. Fief systems proved capable of providing effective mounted warriors across centuries.

Nexus civilisation

If you unify most or all of the steppes, that puts you in contact with a lot of cultures and civilisations. That makes you a nexus civilisation, as Islam was to later become and Western civilisation did still later. You can steal ideas from anywhere you are in contact with, as both Islam and Western civilisation did. But you can also feed ideas into anywhere you are in contact with.

This is precisely what Beckwith argues that the Scythians did. Beckwith points out that Anacharsis (early C6thBC), Buddha (C6/5thBC) and Lao Tze (C5/4thBC) had surprisingly similar ideas: a sceptical, parsed-down, moral logic.

Anacharsis is explicitly Scythian, the latter two operated in or from Scythian border lands. Buddha’s epithet Sakyamuni is ‘Scythian sage’. Saka is one term for Scythians. So, we have Gautama the Scythian sage.

The legend of Lao Tze departing on a water buffalo into the wild actually makes more sense if he was going (back into) the steppes.

Add in Zarathustra (also from Scythian border land), whose ideas also have a clear moral logic, and who Beckwith argues is fairly clearly C7/6thBC, and you have four seminal thinkers all with actual or implied Scythian connections whose ideas helped found the Classical eras in Greece, Persia, India and China.

The big difference between Zarathustra and the other three is that Zarathustra is very much about there being an absolute, and morally compelling, truth. Anacharsis, Buddha and Lao Tze take a much more sceptical view of absolutes and certainty, of what we can know there is.

Monotheism

Beckwith also argues that the Scythians were the first monotheist polity (without being a monotheist society). It is not that they denied the existence of other gods, just that those gods, and everything else, was created by their (royal clan’s) God.

So, their Great Kings, their royal clan, worshipped, and were legitimated by, the God of Gods. Once you start calling yourself King of Kings, who else can you be serving, and anointed by, than the God of Gods?

Which fits in with my hypothesis about why the Middle East is the hotbed of monotheism. Monotheism creates a unified moral and ritual order that can operate among pastoralists and farmers. So social selection favours monotheism when there is a strong advantage in having a shared ritual and moral order across the farming-pastoralist divide.

The Middle East is where that ecological boundary is most convoluted and porous, with the most shifting between pastoralism and farming. Hence the Middle East tends to (socially) select for monotheism (and, if anything, for more thorough monotheism over time).

Beckwith argues that a key difference between Cyrus and Cambyses versus Darius was Darius nailed his colours to the monotheist mast (hence promoting the partnership of Medes and Persians) while Cyrus and Cambyses were polytheists (hence being all about restoring local worship patterns). Thus, the Greeks preferred Cyrus the polytheist over the monotheists Darius and Xerxes who invaded Greece proper.

History and myth

The picture that Beckwith constructs, from textual and archeological evidence, of the Scythians, their importance and role, and of what became known as the Achaemenid Empire, is rather different from the conventional future that has come down to us. This is particularly so regarding the Scythian-Median-Elamite-Persian Empire, the first farming mega-empire.

In telling this history of a continuing empire, Beckwith strongly critiques conventional reliance on Greeks telling tales, particularly on Herodotus. Beckwith argues that the Herodotus that comes down to us is a bit of a literary palimpsest, with various later copyists adding their bits in. Hence the contradictions within the text. Additions which come from further and further away in time from the origins of the first farming mega-empire. Hence also the need to examine the textual and archaeological evidence that has come down to us to critically test Herodotus and other Greek sources.

There were four civilisations that produced serious traditions of writing history. One was the Greeks, from whom the Romans also acquired a strong tradition of writing history. One was the Chinese. The last was Islam.

To the extent that medieval Europe had a tradition of history (mostly chronicles), it came from the Greeks and the Romans. It was Renaissance and Enlightenment re-engagement with the legacy of classical Greece and Rome that led to modern Western writing of history.

The Romans and the Muslims took to writing history in large part for legal reasons. The Romans produced the first great legal culture and what happened when is crucial in law.

Sharia is based on the revelations and actions of Muhammad, and decisions of the Rashidun caliphs. Hadiths come with chains of transmission, which Islamic scholars have proved more than willing to argue over. These are all things grounded in history, and in claims about history: hence Islam’s very rich historiographical tradition.

Brahmin civilisation produced amazing mathematics and astronomy and vibrant philosophical traditions. What it did not produce was history. It did not produce chronicles and did not even produce much in the way of archives.

The earliest chronicle in India which is not Muslim is the Rajatarangini, written in Kashmir in the C12th, and which is fairly clearly a result of centuries of interaction with Islam. Revealingly, it is written in verse and includes considerable legendary material. In other words, it is written in a classic mythic form.

This lack of a historical consciousness is why it is so difficult to write histories of India and why so many dates in Indian history are so vague. Nor is it hard to work out why Brahmin civilisation is so weak on history. It is an intensely hierarchical civilisation. So intensely hierarchical that it relies greatly on a mythic conception of the past.

To write genuine history requires a strong sense of the contingency of events and a strong sense of a unified human nature. That people did things for common human reasons. But a strong sense of a common human nature is precisely what an intensely hierarchical civilisation is going to resist. The Brahmins were not guardians of history, they were managers of myth and ritual.

As Donald E. Brown points out in Hierarchy, History, and Human Nature: The Social Origins of Historical Consciousness, Greek, Roman, Chinese and Islamic civilisation all had a strong meritocratic streak, a strong sense of a unified human nature, and a strong interest in reading the future (including by divination). Their traditions of writing history both reflected and reinforced that.

None of the above makes one immune to historical myth-making. Herodotus (and likely later copyists thereof) seems to have fed us some myths about the history of the Iranian plateau.

Central to doing history is to take the available evidence seriously. Which is precisely what Christopher Beckwith has done yet again in The Scythian Empire.

*Includes protectorates (aka vassal states).

References

Christopher I. Beckwith, The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China, Princeton University Press, 2023.

Donald E. Brown, Hierarchy, History, and Human Nature: The Social Origins of Historical Consciousness, University of Arizona Press, 1988.

Elizabeth A. R. Brown, ‘The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe,’ The American Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Oct., 1974), 1063-1088.

J. H. Elliott, Imperial Spain 1469-1716, St Martin’s Press, [1963], 1964.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, 1977, 85:1, 59-77.

Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted, Clarendon Press, 1994.

Thank you Lorenzo for this handy summary covering one of a bucketlist of byways touched on but left unexplored by my education (which straddled the classical and the computer ages and therefore left me "partially informed", as distinct from today's generation who are mis- or dis-informed). Incredible to think we sat there construing Xenophon from the original Greek without knowing who he was, where he was or what war(s) he was fighting, or when (the how was covered in the text)

Interesting - especially regarding who wrote histories - but given we have 8 Scythian gods recorded, they can hardly have been monotheistic. Also, if it was the polytheists who were restoring local religions, it doesn't make sense that the Jews historically were fond of the dualist Zoroastrians.