Property before the state, before law

On Acknowledged Possession (1)

I was intrigued by how China managed to have a massive commercial take-off well before it legalised private commercial property (in 2004). I therefore wrote a 12,000 word essay on the origins and dynamics of property. That is far too long for a Substack post, so I have broken it up into a series of posts. (This post has been renamed, to make the content clearer.)

Have you ever actually read any of the property laws of your country? If you are not a lawyer, the answer is almost certainly no. Yet you act on the basis of who owns what every day. You engage in exchanges of property every time you buy (or sell) something, typically using money in doing so. Almost certainly, without having read the legal tender laws either. You, and the vast majority of fellow citizens, use, buy and sell property without ever having actually read the law of the land on such matters.

How can this be?

It can be so because property as-a-thing-people-do is not founded in law. Property-as-a-thing-people-do is based on convention. (And the same is true of money.)

Strategising agents

Before we get to what conventions are, and why they are so ubiquitous in human societies, it is helpful to establish a basic analytical framework.

Mathematics is the science of structure. Physics is the study of the structure of the universe. Chemistry is the study of material structures. Biology is the study of structures (living organisms) emergent out of material structures.

Social sciences study structures emergent out of biology. Specifically, Homo sapiens and their social behaviour. Emergent phenomena are more complex structures or patterns that have causal effect—for instance, through reaching a scale of operation that enables greater stability.

Information is what is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things. Genes, hormones and perception are all ways of disseminating information.

If we define a living organism as something that uses information and resources to sustain itself, then living organisms display patterns of feedback and response to sustain themselves and to reproduce. Living organisms are thus strategising agents, with the processes of selection acting upon the strategies they use to sustain and reproduce themselves. Those strategies that keep organisms alive long enough to reproduce are selected for.

Feedback and response with outcomes—in this case, survival and reproduction—is all you need for game theory to apply, hence evolutionary game theory. Which, famously, is applicable to “the selfish gene”; to something with no consciousness, cognition or intention.

Hence the term selfish should not be taken to imply or require any level of conscious intentionality. It is better to say that living organisms, as they use information and resources to sustain themselves, and to reproduce, have directedness: intentionality without any implication of emotions or consciousness. Especially as, even in us Homo sapiens, there can be behaviour rooted in evolution that we are not conscious of.

So, the biosphere is made up of strategising agents. Social science studies the patterns of that sub-set of strategising agents known as Homo sapiens.

The social sciences do not study Platonic rational agents. They study Homo sapiens: a particular species of embodied, evolved decision-makers, and the social structures and patterns that emerge out of (and shape) their behaviour.

Yes, evolutionary game theory applies to biological organisms. Yes, it can even be said to apply to genes and alleles (gene sequences). But in the social sciences, we are looking at layers of emergent phenomena and Homo sapiens depart from Homo economicus—the self-interested rationality model of game theory—in specific ways: in ways that are central to our success as a species.

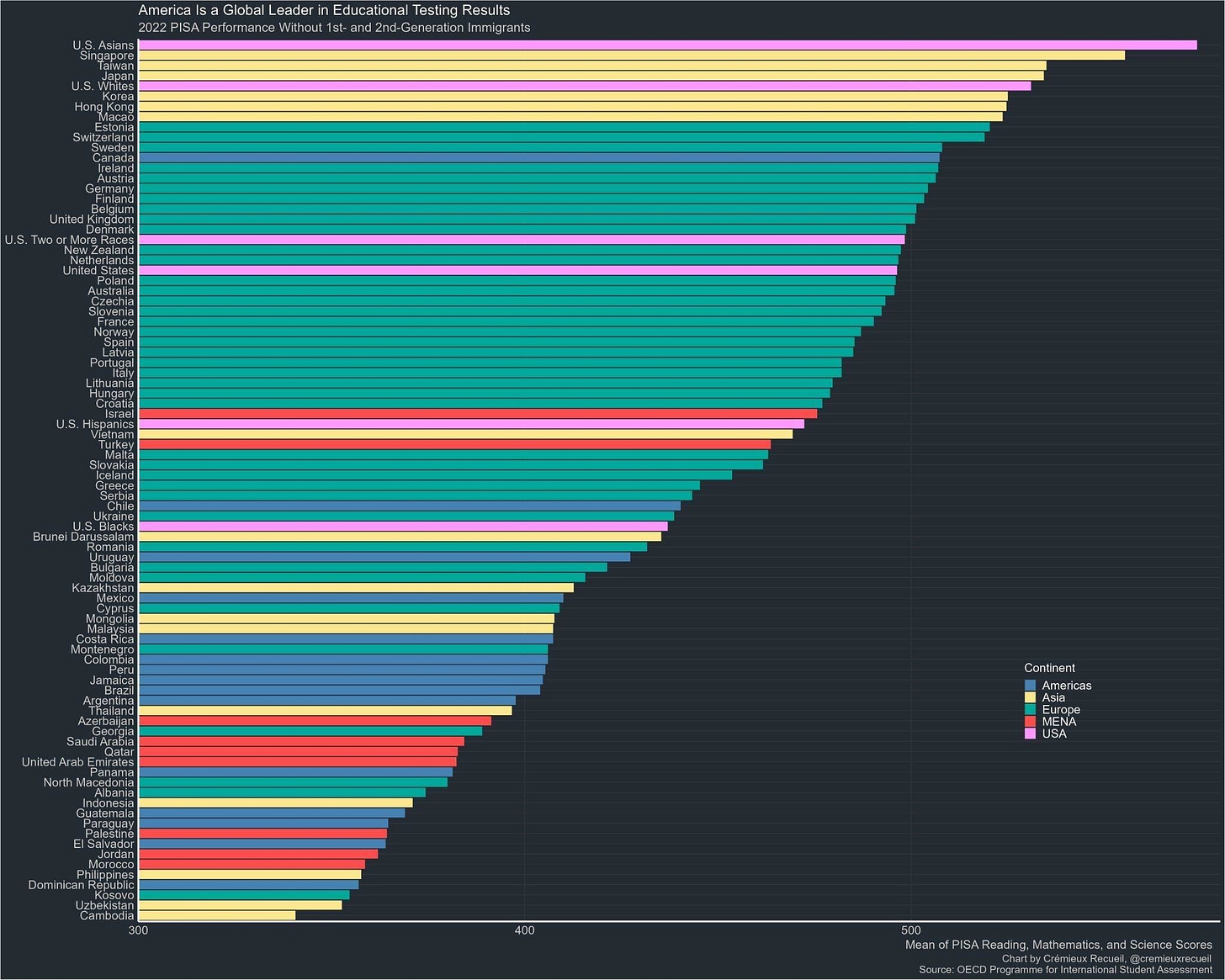

Any claim that Homo economicus has never been found in reality is false. In behavioural labs, Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) have been able to match, even outperform, Homo sapiens in certain competitive strategy games because our primate cousins conform very closely to the predictions of game theory, to Homo economicus. More closely than we typically do.

Yet we are a much more successful species than chimpanzees, with far larger numbers inhabiting a much wider range of habitats. Moreover, that success is directly connected to how we differ as a species from other primates and specifically how we differ from Homo economicus.

As social psychologist Michael Tomasello famously observed, you will never see two chimpanzees carrying a log. They lack the ability to form and carry out the required level of shared attention and intention.

The level of cooperation we display not only requires common attention and intention, it requires common expectations. Expectations are if-then predictions: if A happens, expect B to happen; if P happens, expect Q to happen. There being no information from the future—as information is caused and causality (at least at the necessary levels) does not run backwards across time—we act upon the basis of expectations built up by past experience, using brains primed to recognise patterns and generate if-then predictions, to develop expectations.

Operating with if-then predictions shared with others—that is, congruent expectations—allows people to cooperate much more readily. If my expectations match your expectations, then we can act in ways that do not get in each other’s way.

We can also cooperate to mutual advantage. This is especially so if we can develop mutually intelligible signals that prime such congruent expectations. Generating congruent expectations extends to the whites of our eyes making it easier for others—including our dogs—to judge our intention from where we are looking.

We do various things to signal our expectations. One of the things culture does is to create shared framings and congruent expectations.

Something that can be disconcerting about living in a unfamiliar culture is not having a locally-useful store of such expectations, or understanding the signals involved in generating and sustaining those expectations. Fortunately, we are cognitively primed to quite rapidly build up such a store of expectations and associated signals. One of the many ways by which we are not blank slates.

Though it may be difficult to smoothly adopt all of such signals and expectations, especially as many of them are not entirely conscious acts. One of the mechanisms for social differentiation is using signals-and-expectations that one is so used to, one follows them automatically in a way that outsiders do not. Signals and expectations one may find hard to fully articulate, or even consciously notice.

For we are a highly imitative species. More so than our primate cousins. This is a result of not merely being a group-living species (so are our primate cousins), but from being a highly cooperative group-living species.

Being so readily imitative aids both learning and cooperation. We can imitate first, and work out which bits work later, while signalling our within-group conformity.

One of the crucial differences between our primate cousins and Homo sapiens is that we are a far more normative species, so are able to cooperate much more.

Norms are if-then injunctions: if X applies, then should do Y; if P applies, then should do Q. Our normative capacity, our sense-of-should, evolved as way of making expectations more robustly congruent, enabling more effective cooperation.

We are a highly cooperative species because, lacking claws and rending teeth, our shift to animal foods—we are far more physiologically adapted to hunting and consuming animal foods than are our primate cousins—required very cooperative subsistence strategies. It also very early on involved tool-use: tools that needed to be made, we needed to learn how to make and use, and were possessions. Moreover we have very biologically expensive offspring.

It takes forager children almost 20 years before they learn to forage as many nutrients and calories as they consume. Our children are so biologically expensive because so much of human brain development takes place after birth, there being a limit to the size of infant heads that can exit bipedal pelvises structured for efficient locomotion. (Human childbirth being unusually risky shows that there was very strong selection for brain size.)

Raising biologically-expensive, slow-peaking, human children has required highly cooperative reproduction strategies. Our big brains both enabled, and required, highly cooperative (tool-using) subsistence and reproduction strategies in what was clearly an upward cognitive-capacity-and-cooperation evolutionary selection spiral.

Imitative and normative, so convention-generating

A custom is a thing we repeatedly do because we find it convenient to do so. Having and observing customs generates mutual expectations.

A convention is a bundle of congruent mutual expectations: things we do because we expect other people to do those things. Being a highly imitative species primed to develop expectations, and to provide and read signals, makes it easy for us to generate conventions.

Thus, imitative behaviour plus congruent expectations based on shared signals and common norms is the basis of convention. Norms that can emerge out of repeated interactions.

Norms are played out among agents who can develop such shared sense-of-should expectations. You are never in a normative community with tigers, although people can have norms about tigers. Conventions rely on descriptive norms (should do X because others do X) and tend to be self-reinforcing by creating win-win patterns of interaction.

For conventions are very useful things to have. Language is a set of conventions. We use specific words to refer to specific things because other people use those words to refer to those things. That c-a-t refers to obligate carnivores with whiskers is a convention. That languages are bundles of conventions generated and sustained by repeated interactions is how so many languages (and dialects) can exist.

Children learn languages so readily precisely because they are cognitively primed to imitate others and to absorb specific patterns of information from others. This includes patterns of expectations and associated signals.

Language existed long before states. But so did property. All known human societies have had some concept of property. This includes ownership of what was hunted and gathered, even if such is then shared, and of the tools used to hunt and gather.

Any social animal that hunts is going to have some sense of “this is mine”. To have conventions of property requires some sense of “that is yours”.

Property starts with convention. It starts with mutual acknowledgement of who owns what.

All the benefits of social cooperation include social cooperation regarding things: things found, things made. Who gets to use what, who gets to decide who gets to use what, are fundamental questions for human cooperation. Hence the development of conventions about property.

The value in protecting the ability to interact through conventions of ownership based on mutual acknowledgement is so strong that injunctions against stealing—at least within the relevant in-group, the relevant normative community—are a universal feature of human societies. The conventions of property are thereby reinforced by social norms against (in-group) theft.

Social norms are injunctions to act as expected, with sanctions also being expected to be imposed if such expectations are not fulfilled. So social norms are based on normative expectations reinforced by expected social sanctions. The mechanisms to enforce such norms include criticism, shunning, expulsion, violence (even killing).

Homo sapiens have also developed two forms of status as currencies of social cooperation. One is prestige: status through conspicuous competence or bravery. This encourages people to do things that benefit third parties. The other is propriety: status through conformity to norms. It is often enforced by stigma: hostility to norm-breaking. This encourages people to not do things that harms third parties (and to not be seen to break norms).

Status brings that form of presumptive attention and regard we call respect. The granting or withholding of respect matters to our social interactions. This is especially so as even basic subsistence and child-rearing are cooperative activities. The more mutually dependent we are, the more prestige and propriety are going to matter to us.

Note that while anti-theft social norms can reinforce the conventions of property, such norms emerge out of the conventions of property. The conventions of property come first.

Moreover, such conventions emerge prior to law or the state. The mutual convenience of the conventions of acknowledged possession—the conventions of yours!—can establish functional property without any state action or formal legal structure.

By legal structure I mean rules with remedies: formal rules with consequences for breaking the rules and some mechanism for adjudicating such. Public international law is not really law as it lacks remedies—apart from the very weak one of declarations—or binding adjudication mechanisms. Sovereign states are, indeed, sovereign.

People from different groups can trade by sharing conventions of property. Not being within the same normative community can, however, create trust issues, which further conventions and signals, arising out of repeated interactions, can develop to allay.

Nevertheless, the claim by Adam Smith, in his Lectures on Jurisprudence (1763), that:

property and civil government very much depend on one another

is flatly wrong. Jeremy Bentham is equally in error when he states, in Principles of the Civil Code (1843), that:

property is entirely the creature of law.

Selection complexities

That people can be emotionally committed to punishing norm violators points to our evolved emotional architecture being primed to operate within groups, and even to invest in group cohesion. Nevertheless, any strong notion of group selection does not stand up to examination. There is no evidence for it in other species—eusocial insects such as ants, termites, bees, do not represent cooperation across genetic lineages—and human groups are far too fluid to operate as biologically stable units of selection.

We shift between groups, and mate across group boundaries, far too readily. Indeed, movement and mating across group boundaries are themselves potential parts of selection processes.

As humans, we create, and move between, social niches, rather than compete for some singular, specific-to-a-species, ecological one. Human groups can, however, clearly operate as arenas within which genetic selection operates.

Thus, it is obviously true that the distribution of traits can and does vary between groups, especially if lineages spend long enough as separate breeding populations in different ecological environments or suffer a severe selection shock: such as killing around a quarter of a population, focusing on the educated.

That cultures are collections of life-strategies increases the capacity for distribution of traits to vary between groups.

There is social selection at various levels, but mainly as a discovery mechanism that can operate across groups. For example, that medieval Europe had many competitive jurisdictions that had suppressed kin groups—thereby elevating mechanisms for non-kin cooperation—generated a competitive variety in institutions that gave social selection more to work with.

Things that were shown to work (e.g. drilling troops) then spread by local copying and adaptation, resulting in the development of unusually effective states (and productive societies). These patterns were then adapted and adopted by non-European states, to varying degrees of success. Indeed, since the beginning of the Great Enrichment with application of steam power to railways and steamships in the 1820s, comparative performance between countries and regions has proved to be notably more stable than have levels of prosperity and human development.

Social selection is thus quite different from natural selection, in being much faster and more intentional: indeed much faster because it has so much intention involved. This is much of the function of culture (and institutions): we evolved to be cultural beings able to create institutions because culture and institutions can adapt much quicker than genes, while sustaining higher and higher levels of cooperation. Non-kin cooperation is the Homo sapien super power, which continues to trend upwards.

Group-ish selection—selection to operate within groups—has clearly been very strong within human lineages, given our highly cooperative subsistence and reproduction strategies; and that fellow humans have been our greatest threat for thousands of generations. Hence our development of norms; of prestige and propriety; of conventions of property.

Property as what people do

The basic functional element in property is not formal ratification by a legal system or process, but mutual acknowledgement by interacting persons. Such acknowledgment may be active, or it may be passive acquiescence. Nevertheless, such mutual acknowledgement is all that is needed for people to exercise effective possession of—typically extending to control over—attributes of things and so for property to exist. Indeed, such mutual acknowledgement is what makes any property law functional in day-to-day operation and is required for it to be so.

The old saw that “possession is nine-tenths of the law” points to the fundamental role of mutual acknowledgement for any property system; that property is based on convention, something you do in particular ways because others do so. This applies both to the general acknowledgement of owning that we see in all human societies and the conventions of owning specific to a particular society or community.

We might even call property the grammar—the basic structure—of commerce. Though commerce is something that also develops out of the conventions of property.

Property-as-mutual-acknowledgement generates basic conventions of resource use. If you have something in your possession, the information-economising presumption that simplifies human interaction is that it is, indeed, yours in the senses that matter.

This mutual acknowledgement—as is normal for effective conventions—works because it works for everyone as a general presumption. My acknowledgement of your possession reinforces your acknowledgement of my possession. People can operate on the basis of a common set of mutually-reinforcing, because mutually-beneficial and mutually-aligning, expectations.

Property everywhere and always exists via such information-economising acknowledgement, creating mutually-reinforcing expectations. It can be thought of a pattern of focal or Schelling points—a solution that people tend to choose by default in the absence of communication—based on simple signals using highly salient information. Such a convergence of expectations that does not require complex communication but does require certain commonalities among the agents.

To work, such conventions have to be simple enough to operate quickly and readily, using very limited, but sufficiently salient, information. They typically involve easily-read signals.

Conventions of property that presume informed connection-to-others—as in small-scale foraging communities—can readily evolve to operate in situations of anonymous agents, where we have little or no specific information, and no identified connection, to others—as in large-scale urbanised and mercantile societies. The latter need conventions that generate minimal levels of transaction friction, driven by the pressure to economise on information, to enable mutually-beneficial trades at scale.

A trade is the process of transferring mutually-acknowledged possession of goods or services. All parties to the trade agree to that exchange because they are getting something out of the transfer.

Each party gets the value they perceive from having what the other previously had, or is going to provide, in exchange for what they themselves previously had, or will provide. An exchange they undergo because they value the former more than the latter.

Hence, gains from trade: in cases of voluntary exchange, if both sides did not feel themselves to be better off, they would not have agreed to the trade. It is the same directedness of action that leads us to work to achieve something we value. (That is, labour is directed to what is valued: though it may, or may not be, successful in creating value.)

Even in cases of coerced exchange—providing goods or services to avoid some violent or other penalty—not ending in the death of one party, the coercion works because the transfer is judged better than the alternative by both parties. In the case of the coerced, it is judged better than the alternative after coercion is put into play. In the case of the agent applying the coercion, before doing so.

The purpose, pattern and consequences of the coercion drives our judgement about such coercive exchanges. Taxes and a mugging are both coerced exchanges, but they are not generally regarded as normatively equivalent.

Money also

The same pattern of information salient to those interacting, shared signals, congruent expectations, and being a highly imitative species, also generates money. That is, money arises as a matter of convention. Some of things that have been used as money include:

Beads (whether made of stone, shell, glass or whatever), beeswax, buffaloes, camphor, cattle, cloth (from silk to wadmal, a coarse wool fabric), coca leaves, cocoa beans, coconuts, strings of coconut discs, dye cakes, feather coils, gold dust, weighted gold, grain (notably barley and rice), human heads, logwood (mahogany), tool metals (iron, copper, tin, bronze) in various shapes, plaited palm-fibre rings, pigs, porcelain jars, balls of rubber, salt (including stamped salt cakes), seeds, shells (especially cowries), silver in lumps or shaped, animal skins, slaves, carved stone (a tool material), tea (including in bricks), teeth, tobacco.

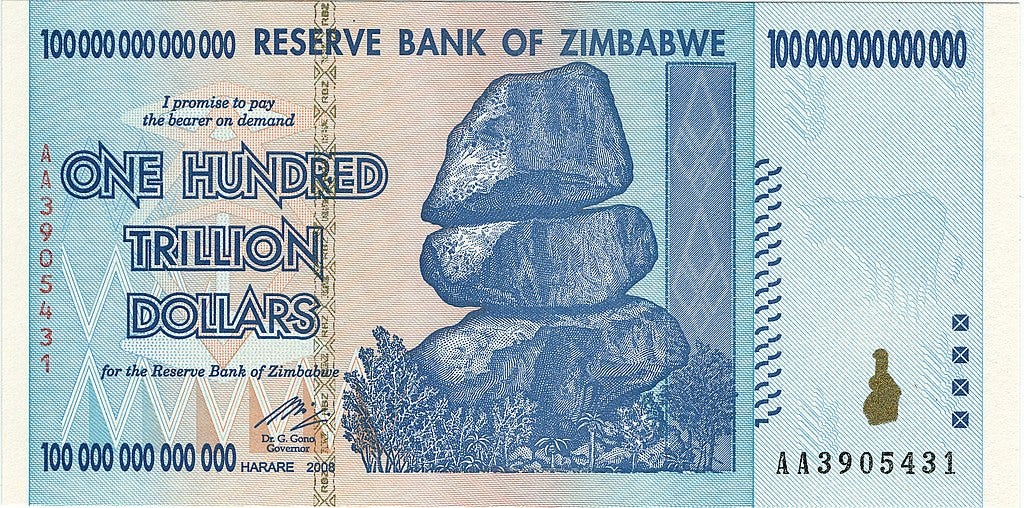

Something is being used as money when its use-value is its exchange-value. It is very useful to have something generally accepted in exchange, as that hugely economises on information (and so search effort). Indeed, that economising on information is so useful, we tend to create money illusion—treating money as a more stable unit of exchange-value than it is.

Most international trade is carried by water, as water is a friction-reducing medium. If money is available, most exchanges will be monetary, as money is a transaction-friction-reducing medium.

The more it becomes known that something is being generally accepted in exchange, the more it will be accepted in exchange. Hence a commodity can become the local currency quite quickly.

An economy without money would be a much smaller economy. (An exchange-good is still a good, providing a service.) Money—by greatly economising on information—is a reaction to an increasing scale of interactions; a mechanism that generates and spreads information; and a mechanism for increasing the level of transactions.

Money can also be how the level of transactions falls, if people sharply increase their willingness to hold—including park in safe (i.e. low-risk) assets—money, rather than spending it. Money then increases the number of transactions less than it did prior to that downward shift in transacting due to an adverse shift in expectations. (Monetary policy is mainly about managing—hopefully anchoring in a stabilising way—expectations.)

Even during hyperinflation—when the local currency is by orders of magnitude the worst store of value available—people will still use money in exchange because it so economises on information. They will just unload it as quickly as possible. Hence hyperinflation spirals, as the faster money loses exchange-value, the more urgently people unload it, so the more it loses exchange-value. Hyperinflation spirals are typically brought to an end by terminating use of that currency and shifting to a new money. That is, by resetting people’s expectations.

The next post in the series will be on property in the informal economy, including grey and black markets.

References

Books

Yoram Barzel, Economic Analysis of Property Rights, Cambridge University Press, [1989] 1997.

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Michael J. R. Crawford, An Expressive Theory of Possession, Hart Publishing, 2020.

Irving Fisher, The Money Illusion, Start Publishing, [1927] 2012.

James Franklin, What Science Knows: And How It Knows It, Encounter Books, 2009.

A. Hingston Quiggin, A Survey of Primitive Money: The Beginnings of Currency, Routledge [1949] 2019.

Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell with Mind And Matter & Autobiographical Sketches, Cambridge University Press, [1944, 1958, 1992] 2013.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Articles, essays, etc

P. W. Anderson, ‘More is Different,’ Science, New Series, Aug. 4, 1972, Vol. 177, No. 4047. 393-396. https://cse-robotics.engr.tamu.edu/dshell/cs689/papers/anderson72more_is_different.pdf

Christopher Boehm, ‘Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy,’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No.3. (Jun., 1993), 227-254 (with Responses by Harold B. Barclay; Robert Knox Dentan; Marie-Claude Dupre; Jonathan D. Hill; Susan Kent; Bruce M. Knauft; Keith F. Otterbein; Steve Rayner and Reply by Christopher Boehm). https://lust-for-life.org/Lust-For-Life/_Textual/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp.pdf

Harold Demsetz, ‘Towards a Theory of Property Rights’, American Economic Review, Volume 57, Issue 2, May 1967, 347-359. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/38c0/4ebc14c2f5fc70a61f4521f6568522413a92.pdf

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Erik P. Hoel, Larissa Albantakis, and Giulio Tononi, ‘Quantifying causal emergence shows that macro can beat micro,’ PNAS, December 3, 2013, vol. 110, no. 49, 19790–19795. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1314922110

Douglas A. Irwin, ‘Adam Smith’s “Tolerable Administration Of Justice” And The Wealth Of Nations,’ Working Paper 20636, October 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20636

Richard Joyce, Review of Michael Tomasello, A Natural History of Human Morality (Harvard University Press, 2016), Utilitas, 2019, 31(2), 207-211. http://personal.victoria.ac.nz/richard_joyce/acrobat/joyce_2019_review.tomasello.pdf

Hillard Kaplan, Jane Lancaster & Arthur Robson, ‘Embodied Capital and the Evolutionary Economics of the Human Life Span’, in Carey, James R. and Shripad Tuljapurkar (eds.), Life Span: Evolutionary, Ecological, and Demographic Perspectives, Supplement to Population and Development Review, vol. 29, 2003. New York: Population Council, 152-182. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/46603844/Embodied_Capital_and_the_Evolutionary_Ec20160618-27827-pd0oin-libre.pdf

C.F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa, & C. Camerer, ‘Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions,’ Scientific Reports, 2014, 4, 5182. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep05182

C. O’Madagain, M. Tomasello, ‘Shared intentionality, reason-giving and the evolution of human culture,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2021, 377: 20200320. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357000359_Shared_intentionality_reason-giving_and_the_evolution_of_human_culture

Steven Pinker, ‘The False Allure Of Group Selection,’ An EDGE Original Essay [6.18.12], (with Responses by Stewart Brand, Daniel Everett, David C. Queller, Daniel C. Dennett, Herbert Gintis, Harvey Whitehouse & Ryan McKay, Peter J. Richerson, Jerry Coyne, Michael Hochberg, Robert Boyd & Sarah Mathew, Max Krasnow & Andrew Delton, Nicolas Baumard, Jonathan Haidt, David Sloan Wilson, Michael E. Price, Joseph Henrich, Randolph M. Nesse, Richard Dawkins, Helena Cronin, John Tooby). https://www.edge.org/conversation/steven_pinker-the-false-allure-of-group-selection

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Coevolving institutions and the paradox of informal constraints,’ Journal of Institutional Economics, 2021, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/CE95D185B7EA557C5D0066FA7D785BCB/S1744137420000600a.pdf/div-class-title-coevolving-institutions-and-the-paradox-of-informal-constraints-div.pdf

David Sun, ‘Arctic instincts? The Late Pleistocene Arctic origins of East Asian psychology,’ Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, Online First Publication, March 3, 2025. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2025-88410-001.html

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Jessica C. Thompson, Susana Carvalho, Curtis W. Marean, and Zeresenay Alemseged, ‘Origins of the Human Predatory Pattern: The Transition to Large-Animal Exploitation by Early Hominins,’ Current Anthropology, Volume 60, Number 1, February 2019. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:da2850f1-f415-4130-9d35-8ed23fdd6b89/files/r2b88qc185

Michael Tomasello, ‘The ultra-social animal,’ European Journal of Social Psychology, 2014, 44, 187–194. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261567999_The_ultra-social_animal

You've remarked before that chimpanzees come closer to Homo economicus than humans do ... but are you sure that's true? Homo economicus respects the conventions of property; it's part of the definition. Do chimps do the same? If one chimp makes it clear that something is his, do other chimps acknowledge the claim and leave it alone, even when the claimant isn't there to defend it? It seems to me that that would require exactly the sort of long-term cooperation humans exhibit and chimpanzees generally don't.

Marvellous analysis, great insights. Thanks.