The niche-creating species

Welcome to the Anthropocene.

It is my practice to post to this Substack a companion piece when one of my Worshipping the Future series essays goes up on Helen Dale’s Substack. This is the second companion post to my paradox of polities essay.

I don’t intend to make more than one companion post a habit but a comment on the paradox of polities post has suggested that a piece on niches would be helpful.

This is why posting a series online is so useful. You get feedback. The equivalent of giving a paper at an academic seminar.

About niches

Living beings use information and resources to maintain themselves. Species occupy niches. A niche being:

the particular way [species] interact with and find a way to make a living in their environment. (Heying and Weinstein)

Individual members of a species compete to occupy available niches for that species. Such competition is a major driver of selection processes.

Niches themselves are subject to selection pressures and can evolve over time as the physical environment changes and as species adopt (or fail to adopt) effective survival-and-reproduction strategies.

Niches are multi-dimensional (so can shrink or expand along various dimensions).

In resource-sparse environments such as deserts, the level of differentiation between niches is likely to be high, as species evolve towards niches with the least competition from other species. Competition for specific niches is likely to be so intense as to leave one species the sole victor.

In resource-dense environments such as jungles, one is much more likely to have lots of overlapping niches (i.e., the level of niche differentiation is much lower), as small differentiations can still find sufficient resources to be sustained.

A similar point applies to social niches in human societies. A larger, more prosperous society can sustain way more variety in social niches than sparse-resources desert foragers.

Sex is odd

Sexual reproduction is very odd. It means that half of one’s offspring (the males) cannot physically produce new offspring. So, there has to be some major selection advantage for sexual reproduction to be so prevalent.

The most salient features of sexual reproduction are:

increased selection processes: selection applies to both parents, plus mating and reproduction, with sexual selection being added to natural selection,

greatly increased variation, as the genetic die is “thrown” with each offspring,

it is used by a huge variety of species, and

is almost universal among species above a certain level of complexity.

So, sexual reproduction generates much more extensive search of survival-and-reproduction possibilities and more ability to capitalise on successful search by selecting for successful strategies. With more organism complexity requiring more “testing” due to more possible vulnerabilities (including from parasites and pathogens). Sexual reproduction effectively more than doubles the range of selection pressures (natural and sexual selection on both parents and on the reproductive process itself) so more rigorously “filtering” organism complexity.

[To put it another way, more complexity both requires more investment and means more ways things can go wrong. Sexual reproduction increases the selection “filters” to increase the chance of investing in viable complexity.]

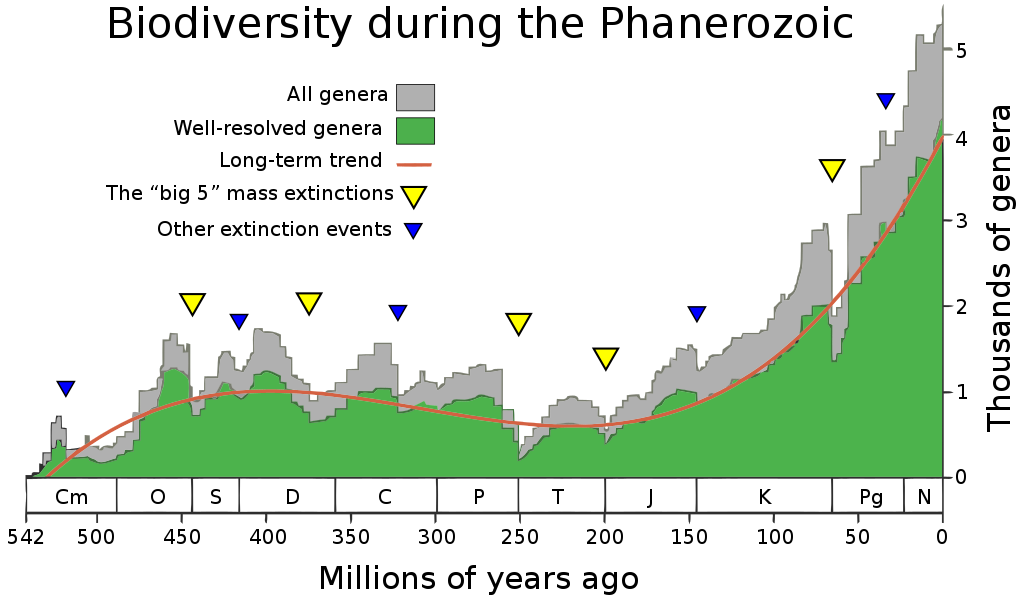

The greater variation and selection generated by sexual reproduction creates more robust capacity to search out, and propagate via, new strategies by a wider range of complex organisms. Including new niches. Hence the development of sexual reproduction has seen an explosion in the number and complexity of species (punctuated by various extinction events).

The more a species can affect its environment, the more it can construct a niche (or niches). No species does that more thoroughly than Homo sapiens, hence the concept of the Anthropocene.

Social selection

What is distinctive about Homo sapiens is our ability to create, and to shift between, niches. A result of our cognitive and social complexity.

We are a highly imitative, normative, group-living, pair-bonding, tool-making species that relies on a great deal of acquiring, processing and using information. We have such long childhoods to allow our brains to develop outside the womb (so they are not restricted in size by trying to get through bipedal thighs) and to manage a very high level of learning.

We don’t merely have natural and sexual selection as do other sexually-reproducing species, we also have social selection. To the extent that we are the only species where it has been common to have mating pairs neither of whom chose the mating. (In many cultures, it has been entirely possible for a bride and groom to first meet on their wedding day.)

We engage in social selection for socially-created niches. Which can still entail considerable competition for niches. The elite over-production thesis argues that too many folk competing for too few elite niches can be a major destabilising factor in societies.

Elite over-production would explain the notable instability of steppe pastoralist polities. Too many sons and grandsons of khagans and khans seeking (and fighting over) elite-level niches in grassland cores not able to be made more productive by human action, given the existing technology.

More generally, members of second-tier elites are classic revolutionaries, seeking to displace those above them.

The shift from foraging to farming represents a shift to smaller niches (farming takes less training, less territory and less day-to-day risks). Also, more numerous niches, both because smaller (in resources and costs) and because farming makes food rather than merely taking-and-processing it from the surrounding environment.

That farming was considerably less metabolically healthy than foraging was much less important. Being able to support many more farming than foraging niches in arable land was decisive, with farming spreading via spread of farmers (who created farming niches).

Social selection has massively increased our ability to create and occupy niches. Hence we exist in the billions across most of the planet while our nearest genetic relatives exist in the thousands in specific habitats.

Creating surplus

Marx’s concept of surplus value slides between a useful concept and polemical disparagement. So is a typical manifestation of activist, hence degraded, scholarship.

Much more useful is the concept of surplus as resources in excess of subsistence. So, mass prosperity is mass access to surplus. But any level of mass prosperity is very rare in history before the Great Enrichment that begins with the application of steam power to transport (steamships and railways) in the 1820s.

Prior to said Great Enrichment, which occurred when technological innovation hit a critical mass, leading to the demographic transition (from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates), we were still under essentially Malthusian dynamics. More food meant more babies. (Ask foragers overwhelmed by invading farmers.)

To create a significant level of surplus meant blocking the consumption of food for subsistence. It meant creating a block on fertility. The most effective way humans found to do that is to take the food away before it can support more babies. Do that, and you can create significant surplus even in largely subsistence societies.

What takes food away after it is produced but before it can support fertility? Taxation.

Consequently, states became the dominant creator of surplus. Their taxing suppressed fertility and created a surplus: production in excess of subsistence.

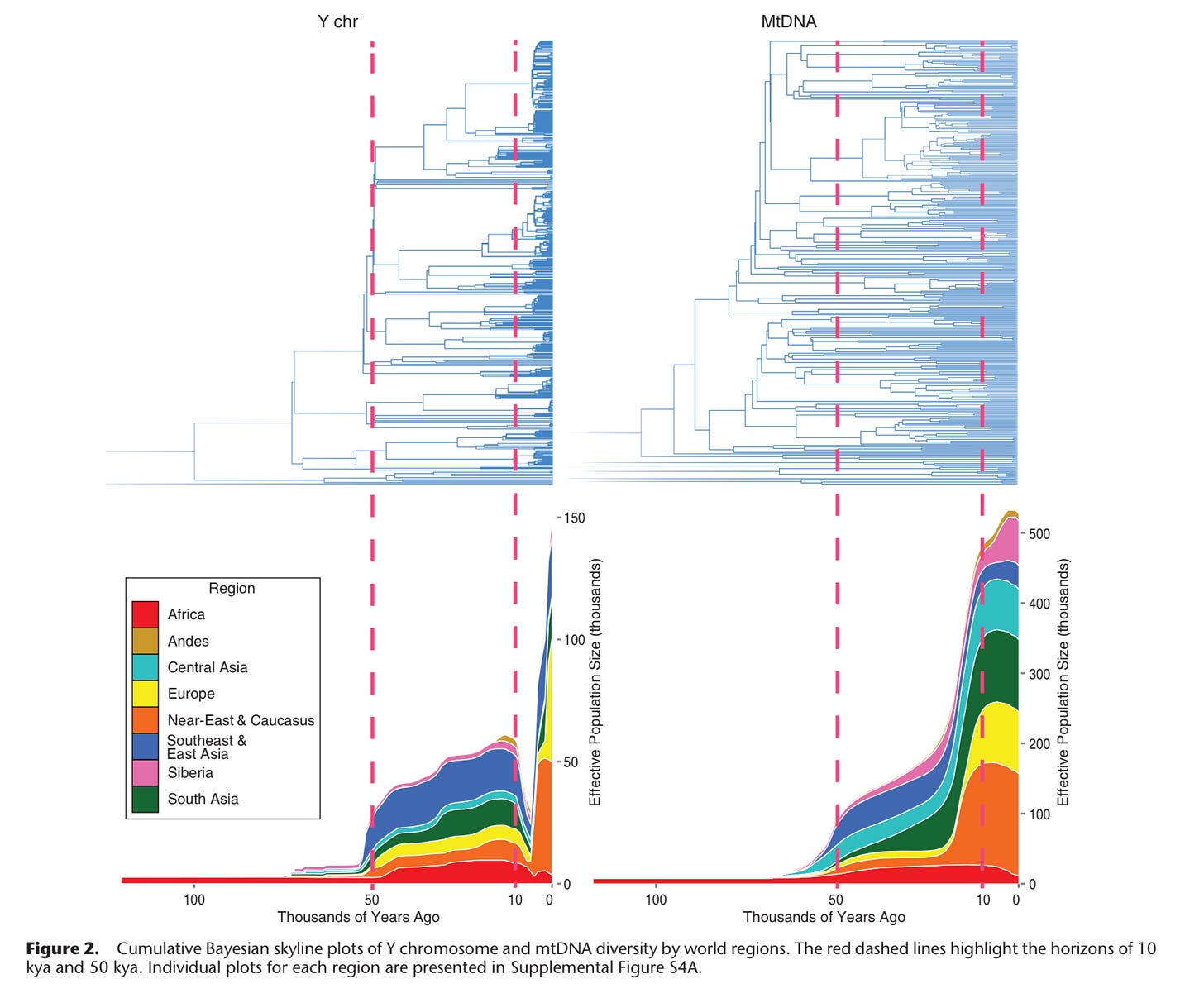

States also suppressed mortality. The pacification by states was so dramatic that it shows up in the genetic record.

After the development of farming and pastoralism, population reached a critical mass so that competition between male teams for land, herds and women became so intense that only about 1-in-17 male lineages made it through what is now known as the Neolithic y-chromosome bottleneck.

Kin-groups fought bitterly over resources. The techniques of social aggression were greater than the techniques of social exploitation. You killed or enslaved enemy males and took their women. (There is no shrinkage in female lineages, which continued to expand.)

Then chiefdoms and states evolved where there was stored food to protect-and-tax. Now, you kept conquered males alive, protecting them so they could pay taxes and produce more taxpayers.

Yes, you were taxing them, so reducing how many children they could support. But you were also protecting them so they could have children. The combination of checks on mortality via pacification and on fertility via taxation created a mostly sustainable Malthusian dynamic.

I say mostly sustainable, because the combination did allow population growth. Over time, farming niches would tend to shrink as they came up against the limits on arable land. So, without any increases in taxation, the tax burden would increase.

The result would be increasing desperation and farmer unrest, even revolts. The surplus available to the state would shrink (you can’t tax regions in revolt and you have to spend resources putting down revolts). This was a significant, recurrent, corrosive pattern within state societies.

Trade and empire

While states dominated the creation and extraction of surplus, they were not the only form of surplus. Producing things for exchange required production in excess of one’s own needs. If you were persistently able to do that, and exchange the results, you could create an income above subsistence, thereby generating surplus.

Which the state would typically tax. States would encourage trade precisely because it was a revenue source. Indeed, the level of trade was crucial in determining the size and scale of states.

Land (stored food, mines, labour services) and trade were the dominant source of state revenue. In the case of land, the income was essentially linear: twice as much land of a given quality would produce twice as much revenue.

What was not linear were administrative costs. They had a strong tendency towards negative returns to scale. Due to high transport, communication and coordination costs, twice as much land would cost more than twice as much to administer. So, land without trade tended to produce small polities.

Trade is different. In the right circumstances, trade could increase faster than administrative costs. Including by increasing land revenues through increased specialisation. So, the more trade, the larger states could be.

Eras of high trade were imperial epochs. The Achaemenid Empire (550BC-330BC) was the first “mega-empire” (controlling at least 1m km2) and coincides with the first steppe-pastoralist empire (the Scythian Empire, c.600BC to c.300BC). Pastoralists being natural traders.

The perennial need for China to import horses (due to lack of selenium in its soil) made the unification of China a major driver of trade across Eurasia. When China was unified (generating more trade), empires across temperate Eurasia flourished. When China collapsed into disunity, empires retreated or collapsed.

The Roman Crisis of the Third Century (235-284) was general across Eurasia and started earlier, kicked off by the collapse of Roman silver mining production. Roman silver having been a basic driver of Eurasian trade, the collapse in its production undermined the trade revenue “cream” that had been sustaining a series of imperiums.

The Han dynasty collapsed (220), the Parthians were overthrown and replaced by the Sassanids (224), the Kushan empire fragmented after 225. By 235, the collapse of Eurasian trade (forcing various peoples to shift to a more taking strategy) caught up with the Roman Empire, which barely survived. Control of the Mediterranean gave it a trade-revenue resource none of the other Empires could match.

We can trace the upward and downward march of trade and empire all the way up to the massive increase in trade with the application of steam power to shipping and railroads from the 1820s onward. This famously saw a dramatic expansion in (maritime) empires, notably the “scramble for Africa”.

The Dynasts’ War of 1914-1918 resulted in a collapse of various land empires: Russian, Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman. The Dictators’ War of 1939-1945 led to the collapse of maritime empires. Nevertheless, states have done well out of our era of rising global trade.

Mercantile states

If a state is sufficiently efficient at pacifying, and the level of trade is sufficiently high, commerce can produce more surplus than the state. This is very unusual in world history. Though even then the state will remain by far the biggest single controller of surplus.

It remains unusual in history for commerce to generate, and collectively control, more surplus than the state. This is certainly not true in modern developed democracies, where the profit share of GDP is around 15 per cent and the tax share of GDP is around 30-50 per cent.

Even in a situation of mass prosperity, where essentially everyone is living above subsistence, that the state grabs twice or more of available surplus, and has dominant coercive power, will make it dominant in structuring society.

References

Books

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India, Pen & Sword Military, 2014.

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy & the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia & Han China, Pen & Sword History, 2016.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011], 2013.

Articles

Jared Diamond, Peter Bellwood, ‘Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions,’ Science, 25 April 2003, Vol. 300, Issue 5619, 597-603.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77.

Monika Karmin et al, ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Research, Apr. 2015, 25 (4):459–466.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144.

Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘Size and Dynastic Decline: The Principal-Agent Problem in Late Imperial China 1700-1850,’ Explorations in Economic History, Volume 54, 2014, 107-127.

Peter Turchin, ‘A theory for formation of large empires,’ Journal of Global History, 2009, 4, 191–217.

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077.

Agree 100% and glad to meet someone who is developing these concepts so well. I have a series of posts which range from the Anthropology of the Neolithic, through the biology of mitochondrial physiology, to our current obsession with computers. I came to similar conclusions about roots of the deal we made with civilizations. An offer we cannot? refuse. And with the role of the Anatolian farmers in Europe to the demise of the Neolithic there. Difficult to submit these ideas to the kind of serialized and unindexed short pieces we write on SubStack.

Thanks for this, Lorenzo; will draw people's attention to it when I publish your next essay on my substack.