Bravado in the absence of order (2)

Stigmatisation, under-policing and “self-help”.

This is the second part of a re-working of an essay published in Aero Magazine in 2019. The first part is here.

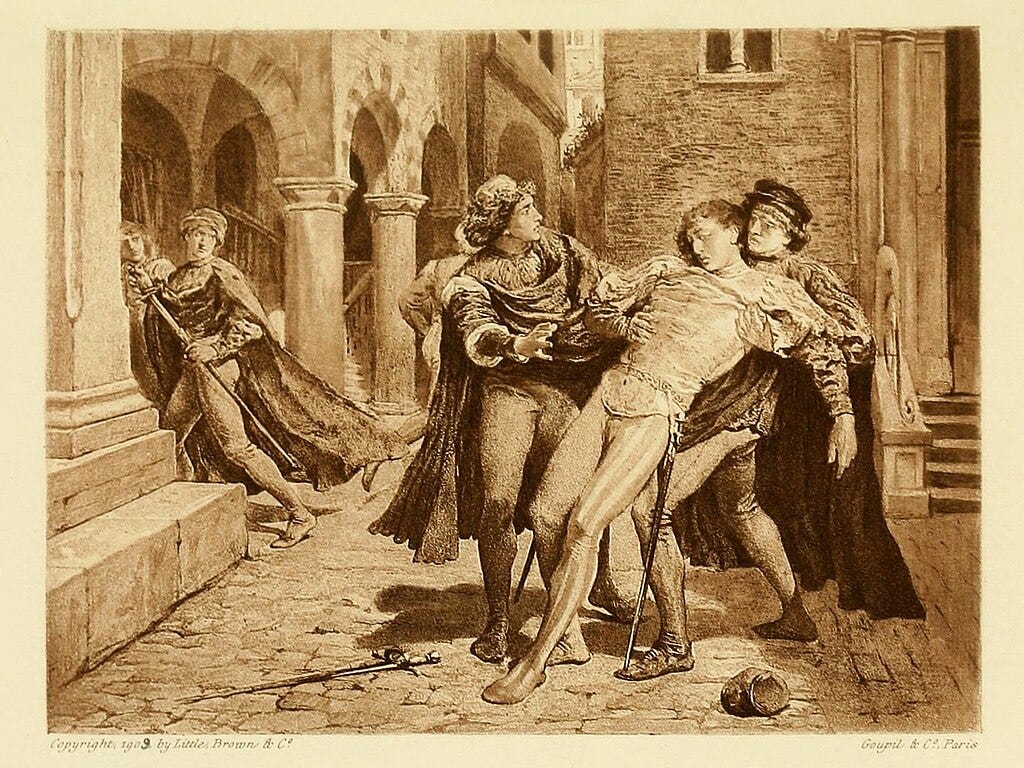

Bravado culture

Social science distinguishes between honour culture—where (usually) males protect themselves and theirs by signalling a willingness to violently defend their reputation, the public signifier of their defended social space, with insults to be avenged in blood—and dignity culture. In the words of sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning, in a dignity culture:

Rather than honor, a status based primarily on public opinion, people are said to have dignity, a kind of inherent worth that cannot be alienated by others. Dignity exists independently of what others think, so a culture of dignity is one in which public reputation is less important. Insults might provoke offense, but they no longer have the same importance as a way of establishing or destroying a reputation for bravery. It is even commendable to have “thick skin” that allows one to shrug off slights and even serious insults, and in a dignity-based society parents might teach children some version of “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” – an idea that would be alien in a culture of honor. People are to avoid insulting others, too, whether intentionally or not, and in general an ethic of self-restraint prevails.

The current enforcement of fragility culture is not an improvement.

Honour cultures are a manifestation of do-it-yourself—DIY aka self-help—public order, operating in localities with low expectations of state protection. In the words of a study of the Scots-Irish culture of honour:

The culture of honor is a private justice system and a self-protection ethic, whose purpose is the defense of a reputation.

In Europe, the shift from the relatively violent honour culture of the medieval period to the far less violent post-medieval dignity culture was fundamentally based on states willing, able and trusted to impose the level of public order capable of supporting the much-decreased level of violence a dignity culture needs so as to be established and thrive. Hence there was a systematic post-medieval decrease in crime in European societies, particularly homicide, that started in northwest European societies and then spread south and east.

The sort of reasons that—overwhelmingly male—folk kill each other for in medieval court records are much the same reasons as—overwhelmingly male—folk kill each other in contemporary African-American urban communities. Consider this 1278 case in London, from court records:

Symonet Spinelli, Agnes his mistress and Geoffrey Bereman were together in Geoffrey’s house when a quarrel broke out among them; Symonet left the house and returned later the same day with Richard Russel his Servant to the house of Godfrey le Gorger, where he found Geoffrey; a quarrel arose and Richard and Symonet killed Geoffrey.

Change the names, swap mistress for girlfriend, servant for gang member, and it becomes a commonplace tale of contemporary urban America as it was a commonplace tale of urban medieval England. But medieval Europe lacked a state with the capacity to impose trusted public order. The contemporary American state, by contrast, lacks the informed willingness to do so within African-American communities.

In his 1920 pamphlet Crime in the America and the Police, Raymond B. Fosdick reports the following:

In Indianapolis in 1919, a negro shot and killed another following a quarrel over a girl. Upon apprehension, the perpetrator admitted the act, but was freed by the Grand Jury presumably upon the ground of justification in killing a trespassing rival. Upon release from custody he called at the coroner’s office to collect his pistol which he had left by the body of his victim and which had been held in evidence.

So far, so medieval honour culture. A few sentences later, Fosdick continues:

“We have three types of homicide”, I was told by the chief of detectives in a larger southern city. “If a n*gger kills a white man, that’s murder. If a white man kills a n*gger, that’s justifiable homicide. And if a n*gger kills another n*gger, that’s one less n*gger”. While of course brutally exaggerated, the statement is none the less too nearly a correct portrayal of the actual conditions of public opinion in many parts of the country to be altogether or even largely discounted.

This is as explicit a statement of abandonment—or, at least chronic under-provision—of public order for African-American communities as one can imagine. This persisting history which has led to, completely understandable, levels of what sociologists call legal cynicism. The recurring consequences of such multi-generational stigma then create internalized expectations which affect behaviour.

African-American writer and essayist James Baldwin’s 1962 essay, Letter from a Region of My Mind, expresses the alienation powerfully:

But the Negro’s experience of the white world cannot possibly create in him any respect for the standards by which the white world claims to live. His own condition is overwhelming proof that white people do not live by these standards. ... In any case, white people, who had robbed black people of their liberty and who profited by this theft every hour that they lived, had no moral ground on which to stand. They had the judges, the juries, the shotguns, the law—in a word, power. But it was a criminal power, to be feared but not respected, and to be outwitted in any way whatever. And those virtues preached but not practiced by the white world were merely another means of holding Negroes in subjection.

It turned out, then, that summer, that the moral barriers that I had supposed to exist between me and the dangers of a criminal career were so tenuous as to be nearly non-existent. I certainly could not discover any principled reason for not becoming a criminal, and it is not my poor, God-fearing parents who are to be indicted for the lack but this society. I was icily determined—more determined, really, than I then knew—never to make my peace with the ghetto but to die and go to Hell before I would let any white man spit on me, before I would accept my “place” in this republic. I did not intend to allow the white people of this country to tell me who I was, and limit me that way, and polish me off that way. And yet, of course, at the same time, I was being spat on and defined and described and limited, and could have been polished off with no effort whatever.

And the police were so often the most active and frightening instrument of those humiliations:

One did not have to be very bright to realize how little one could do to change one’s situation; one did not have to be abnormally sensitive to be worn down to a cutting edge by the incessant and gratuitous humiliation and danger one encountered every working day, all day long. The humiliation did not apply merely to working days, or workers; I was thirteen and was crossing Fifth Avenue on my way to the Forty-second Street library, and the cop in the middle of the street muttered as I passed him, “Why don’t you n*ggers stay uptown where you belong?” When I was ten, and didn’t look, certainly, any older, two policemen amused themselves with me by frisking me, making comic (and terrifying) speculations concerning my ancestry and probable sexual prowess, and, for good measure, leaving me flat on my back in one of Harlem’s empty lots.

The former slave States of the American South, under the Jim Crow system, systematically failed to provide that level of public order in the segregated communities inhabited by former slaves and their descendants. They were certainly not trusted by them to do so. The public order needed to reliably sustain a dignity culture was absent.

Here, the legacy of slavery matters beyond its legacy of stigmatisation. The remnants of African heritages that were left after the atomising social churning of slavery failed to generate the embedded, powerful family or kin structures, and social capital, required to overcome that insufficiency of public order, though Church congregations tried.

The clan/guild/secret society structures of Chinese communities—who had a long history of villages establishing and maintaining their own internal social order—were a very different matter. This despite the considerable stigmatisation of Chinese immigrants. Even more so as—for reasons discussed in the previous post—populations with Sub-Saharan African ancestry have stronger patterns of reactive aggression, putting more stress on social order, while populations with East Asian ancestry show less reactive aggression.

The result of chronic under-policing was the development of an honour culture in the segregated communities. This is better labelled as bravado culture, as it is very much a “street” culture, a subordinated, culture.

The medieval honour culture centred on a bellicose nobility and knightly gentry to whom rulers delegated both local extraction of surplus and provision of armed services for internal control and external warfare. By contrast, a bravado culture lacks elite endorsement. It both signifies and—with its resultant much higher levels of violence—justifies a lower level of public order (as measured by, for example, crime clearance rates) which can amount to a form of social abandonment.

Low homicide clearance rates means that people are literally getting away with murder. That drives people towards the “self-help” of bravado culture.

Bravado culture then generates increased pro-active aggression—System Two/slow thinking homicides—via feuds. It generates increased in-the-moment reactive aggression—System One/fast thinking homicides—as the young males who are the most likely victims of violence, dealing with other young males who are even more so the most likely perpetrators of violence, “puff themselves up” to minimise the chance of being victimised.

Stigmatisation is about how people are perceived: stigma is negative ascription of others. If some group is seen as inherently violent—as were “the masterless men/poor white trash” of the Antebellum South and the “black” targets of Jim Crow’s racialised exclusions and oppressions—and are so stigmatised that bad outcomes are acceptable, are seen as “natural”, even preferred; their communities are then under-provided with, or even starved of, policing services. This results in much higher crime levels, which then supports stigmatisation, creating stereotypes which are accurate, self-reinforcing and, to that scale, the result of stigmatisation—stigmatisation that obscures, even hides, the reality of under-policing.

Table: Male homicide rates per 100,000 people

Thus, the predictable result of DIY public order was a much higher level of violence—particularly homicide—in the segregated descendants-of-American-slaves communities. That the overall male homicide death rate in descendants of American slaves communities was twelve times that in Euro-American communities in 1950, when descendants of American slaves were a tenth of the US population and their family structure was largely intact, speaks to the long-term failures in providing public order in those communities. The fall in that homicide ratio since indicates some converging of performance by police jurisdictions in the US, but from a low benchmark.

High homicide rates can be seen in a wide range of urban environments where the state fails to impose an adequate level of public order—notably in localities within Latin American cities. Cities that reach homicide rates comparable to those in descendants-of-American-slaves communities within US cities. Africa, where clan and lineage systems still operate to support social order, tends to have lower homicide rates, though less so in cities with lots of recent immigrants.

Of the 50 most homicidal cities in the world in 2017, three were in Africa (all in South Africa: Capetown, Nelson Bay Mandela and Buffalo City); four in the United States (St Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, New Orleans); one was in the Caribbean (Kingston, Jamaica) while the remaining 42 were in Latin America. Of the 20 countries with the highest homicide rates, two were in Africa (South Africa and Namibia); eight in the Caribbean; and remaining ten were in Latin America. Latin America and the Caribbean have eight per cent of the world’s population but suffer about a third of the world’s homicides. Yet, when Latin Americans move to the US, their homicide rates drop dramatically (and are converging on the rate among Euro-Americans)—in itself, a reason to migrate.

This simple pattern undermines “racial” explanations for high violence rates among African-Americans, as does the comparison with medieval European or contemporary Latin American homicide patterns. In any pattern of human behaviour, “race” is always embedded within culture, within a polity, and within the dynamics of locality. That Latin American cities have homicide rates comparable to those scholars have estimated for European societies in the medieval period is shocking; that African-American communities do—in a much richer country—is appalling.

Part 3 will conclude the reworking of the original essay, discussing stereotypes and cultural clashes, including the effects of anti-police activism. Part 4 will finish the series by reviewing Jens Ludwig’s book Unforgiving Places and consider possible policy responses.

References

Lukas Althoff and Hugo Reichardt, ‘Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery,’ Hoover Institute Working Paper 23005, June 2023. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/LRP WP 23005.pdf

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Bradley Campbell, Jason Manning, ‘Microaggression and Moral Cultures,’ Comparative Sociology, January 2014, 13(6):692-726. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272408166_Microaggression_and_Moral_Cultures

Manuel Eisner, ‘Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime,’ Crime and Justice, 2003, 30:, 83-142. https://www.vrc.crim.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/manuel-eisner-historical-trends-in-violence.pdf

O¨rjan Falk, Ma¨rta Wallinius, Sebastian Lundstro¨m, Thomas Frisell, Henrik Anckarsa¨ter, No´ra Kerekes, ‘The 1% of the population accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions,’ Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2014, 49, 559–571. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3969807/

Raymond B. Fosdick, Crime in America and the Police, Century, 1920. https://archive.org/details/crimeinamericapo00fosd

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Pauline Grosjean, ‘A history of violence: The culture of honor and homicide in the U.S. South,’ Journal of European Economic Association, 2014, 12 (5), 1285–1316. https://www.uts.edu.au/globalassets/sites/default/files/121017.pdf

David S. Kirk and Andrew V. Papachristos, ‘Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neighborhood Violence,’ American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 116, No. 4 (January 2011), 1190-1233. http://users.soc.umn.edu/~uggen/Kirk_AJS_11.pdf

Jens Ludwig, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Brendan O’Flaherty, Rajiv Sethi, ‘Homicide in black and white,’ Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 68, Issue 3, 2010, 215-230. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094119010000343

Jonathan St. B.T. Evans, ‘In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning,’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.7 No.10 October 2003, 454-459. https://faculty.weber.edu/eamsel/Classes/Methods (3610)/Old Sections/Fall 2010/Fall 2010 Project/Evans (2003).pdf

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS January 9, 2018, Vol.115, No.2, 245–253. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1713611115

Insightful, important essay. I found myself bringing up dignity culture to some students yesterday, vis-a-vis the guillotine. (There was a subtext, since this particular French female student had been among those to complain that I was 'belittling' them by using the Socratic method). The nobles executed before Madame du Barry -- Marie Antoinette -- went to the guillotine with dignity, whereas Du Barry wailed and begged for mercy.

It was ironic how excited she got when describing some medieval torture involving a rat trying to claw its way out of a metal ball.

Anyway, even though Du Barry's wailing sent some modicum of pity in motion, I find dignity ideal. It takes such incredible restraint -- a quality and a skill.

The director who reported the students' complaint to me (they felt "anxious and uncomfortable") advised NOT CHALLENGING THE STUDENTS. There's a heavy, rather oppressive matriarchal atmosphere in this department (the entire university) that places emotion over reason. I see this among friends who can't even read or process any information about Trump in an objective manner. My colleagues are given to catastrophizing. I am obligated to make students feel "safe and comfortable" more so, it seems, than pushing them to think critically.

This isn't going to end well. I don't understand why they fail to connect their causes to actual effects.

Dignity culture, honor culture, norms, shame, excellence... all concepts that seem to have quietly disappeared without anyone noticing.

https://jmpolemic.substack.com/p/the-war-on-norms