Bravado in the absence of order (3)

Stereotypes and cultural clashes.

This is the third and final part of a re-working of an essay published in Aero Magazine in 2019. The first part is here and the second here. Part 4 will finish the series by reviewing Jens Ludwig’s book Unforgiving Places and consider possible policy responses.

In his A Renegade History of the United States, historian Thaddeus Russell writes:

In the summer of 1957, a Baptist preacher in the segregated South issued a series of fiery sermons denouncing the laziness, promiscuity, criminality, drunkenness, slovenliness, and ignorance of Negroes. He shouted from the pulpit about the difference between doing a “real job” and doing “a Negro job”. Instead of practicing the intelligent saving habits of white men, “Negroes too often buy what they want and beg for what they need.” He suggested that blacks were “thinking about sex” every time they walked down the street. They were too violent. They didn’t bathe properly. And their music, which was invading homes all over America, ‘plunges men’s minds into degrading and immoral depths’. (P.295)

That Baptist preacher? The Rev. Martin Luther King Jnr. As Russell points out, a substantial proportion of Martin Luther King’s speeches and writings were directed against moral failings within African-American communities—something that contemporary academe memory-holes .

For decades, prominent leaders among the descendants of American slaves critiqued, or denounced, the level of violence within their communities.

Stereotypes

Bravado culture—where (mostly) males engage in “self-help” protection by their willingness to violently defend their “rep”, their social space, to avoid being victimised—became entrenched within descendants-of-American slaves communities that were (as discussed in the preceding post) systematically under-policed. Bravado culture—an honour culture without elite endorsement—was both a response to, and a cause of, the high homicide social equilibrium thereby established within those communities. This pattern continued when the descendants of slaves migrated en masse to northern cities.

The ongoing failure to impose sufficient public order—as evidenced by dramatically lower homicide clearance rates within African-American communities—not only allows the highly violent to be more violent, it increases the incentive to be violent, both as retaliation and as pre-emption. That is precisely why honour cultures in general—and bravado cultures in particular—have the dynamics they do; including their violence being overwhelmingly male-on-male violence.

In accordance with the tendency for social stereotypes to be (relatively) accurate, a high-violence stereotype became established regarding descendants of American slaves. As economists Glenn Loury and Rajiv Sethi point out, once this violent stereotype was established, it reinforced the high-homicide (and high-robbery) social equilibrium.

Social factors move thresholds of violence up or down the tails of “normal” bell-curve distributions of cognitive traits. As noted in the first post, crime is overwhelmingly a tail effect. Swedish research on violent crime convictions over a 30 year period (1973-2004) found that almost two-thirds of convicted violent crimes were committed by one percent of the population, while less than four percent of the population committed all the violent crimes.

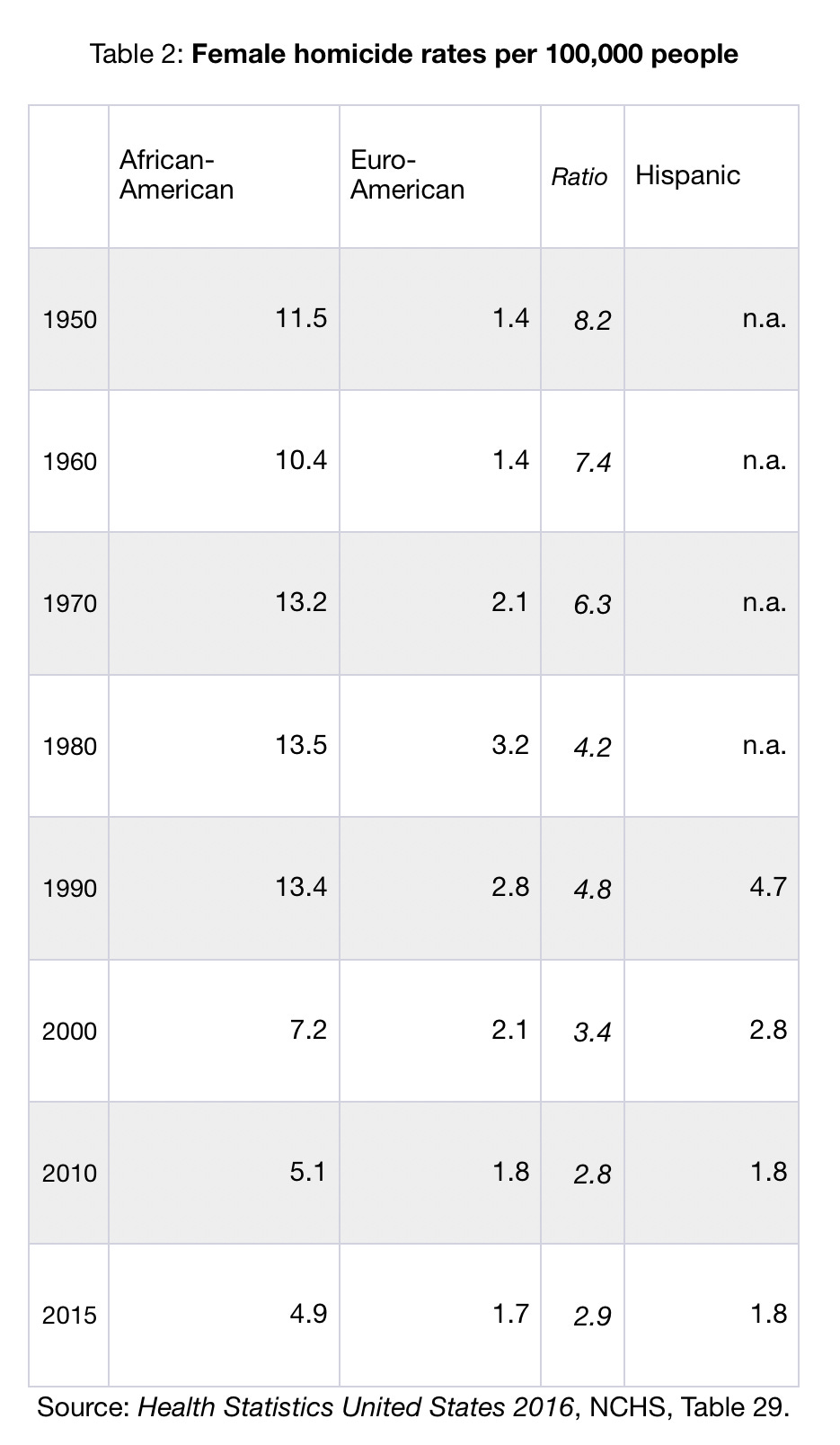

That four percent was seven per cent of the male population and less than one percent of the female population. The male-to-female ratio of violent crime is much the same as the recent Euro-American/African-American homicide ratios, but is rather more stable than the latter.

A “three strikes and you’re out” policy for violent crime—that is, where they themselves committed an act of criminal violence—has some plausibility as it targets the highly violent. It has less plausibility than one might think, given that 75-80 per cent of US homicides are “in the moment” homicides from confrontations going awry.

Needless to say, it would be much better to successfully interrupt the process of physical confrontations occurring, becoming violent when they occur, then becoming deadly, than leaving it to imprisoning-after-the-fact. Getting homicide clearance rates up so as to drive “self-help” violence down is very much part of that.

Including non-violent crimes in the three strikes is, however, an expensive way to be socially stupid, as—even apart from the problems of imprisonment—given the dramatic imbalances by sex in incarceration rates, increasing the number of absent males in order-starved communities leads to (teenage and older) women competing for the reduced supply of (teenage and older) men, who compete with each other. This increases the strength of bravado culture, encouraging violence rather than suppressing it.

Shortage of men undermines marriage, exacerbated by African-American men having a greater propensity to “marry out” than African-American women, and is antipathetic to fathers being present in homes. Economist Raj Chetty’s multigenerational analysis has identified high rates of present fathers as a strong positive factor for African-American males, even for those raised in one-parent households. Present fathers provide both role models and locals potentially able to defuse confrontations that might otherwise spiral into potentially fatal violence.

The political influence of prison unions is a factor in this over-incarceration. Nevertheless, given that deterrent effect is a function of chance of being caught and severity of punishment, elevated African-American incarceration rates may be in part a response to the low crime clearance rates in their communities. The high rates of violence are treated as “normal”, with low crime clearance rates to be compensated via “three strikes”—so presumptive “coverage” of not cleared homicides and assaults—rather than being a result of public policy choices: not of “racist” policing, but the under-provision of effective policing, and local weakness in other supports of social order.

Stigma is the negative ascription to groups or individuals. Such stigmatisation cannot, as economist Glenn Loury points out, be simply equated with racism-as-discrimination. Indeed, stigmatisation is a much broader phenomena than racism—especially given that the ostentatiously anti-racist are typically avid practitioners of point-and-shriek moral abuse stigmatisation who, as is normal for stigmatisation, blame the targets of their denigration for being denigrated.

Some behaviours should be stigmatised and the sacralisation of the “marginalised” can be quite toxic when it removes, even reverses, pro-social stigmatisation. Stigmatising entire groups due to the behaviour of small minorities thereof is a very different matter. Such stigmatisation is also socially corrosive, especially when it leads to policy failures that enable or spread toxic patterns.

Racialising identity

Talking about racism instead of stigmatisation both perpetuates race talk and narrows—indeed, fences off—the phenomena. As none of us behave as members of a “race” stripped of culture, locality, etc., racialisation of identity—lumping people by continental ancestry—is never a good move. It is, however, excellent for divide-favour-and-dominate strategies, whether by Jim Crow racists or modern “woke” left-progressives.

For reasons discussed in the first post—and which will be expanded in the fourth post—populations of Sub-Saharan African descent can be expected to have higher rates of reactive aggression—so violence—than, for instance, populations of East Asian descent. This means that populations of Sub-Saharan African descent are more vulnerable to failures in social order, remembering that those most at risk of such violence are other people of Sub-Saharan African descent.

As young men dominate violence, youth surges also put more pressure on social order. So does increased income from illegal markets that—in the absence of legal means of dispute resolution—multiply confrontations and “self-help” dispute resolution. Elevated rates of reactive aggression are not, however, something that public policy is helpless to deal with.

Stigmatisation-by-category rather than for individual behaviour (the content of one’s character) leads to not applying the same rules to everyone and undermines providing equivalent services. This is true whatever particular category hierarchy is being enforced by the stigmatisation—for instance, person of colour over “white”, female over male, gay over straight, Muslim over Christian, trans over cis; or the reverse thereof.

One of the ironies of our time is that those who are most enthusiastic in invoking Hitler as the secular Satan also engage in the politics of racialising identity and morally ranking people by group—including by the melanin content of their skin. They just largely reverse his hierarchy. Hence the whole Whiteness nonsense: a pseudo-sophisticated way to rate people—and their heritages—by the melanin content of their skin. The iron law of “woke”/progressive projection strikes again.

The more one’s analysis relies on invisible sociological gremlins—e.g. “disparate impact”—the less it is directed to practical solutions. This is especially as “racism” has become more of a metaphysical sin via invisible sociological gremlins than a grounded analysis of human behaviour.

Then again, practical solutions are not the point of such sacralisation/demonisation-by-category; status and dominance games are the point; divide-favour-and-dominate games are the point. Indeed, if being of a sacralised-because-marginalised group confers status and social leverage within elite circles, then one’s group achieving the same outcomes as everyone else becomes more of a threat than a goal.

The deadly consequences of anti-police activism

The most effective way police reduce homicide rates is by being present to interrupt and defuse confrontations. Police who are sufficiently respected are directed towards such confrontations.

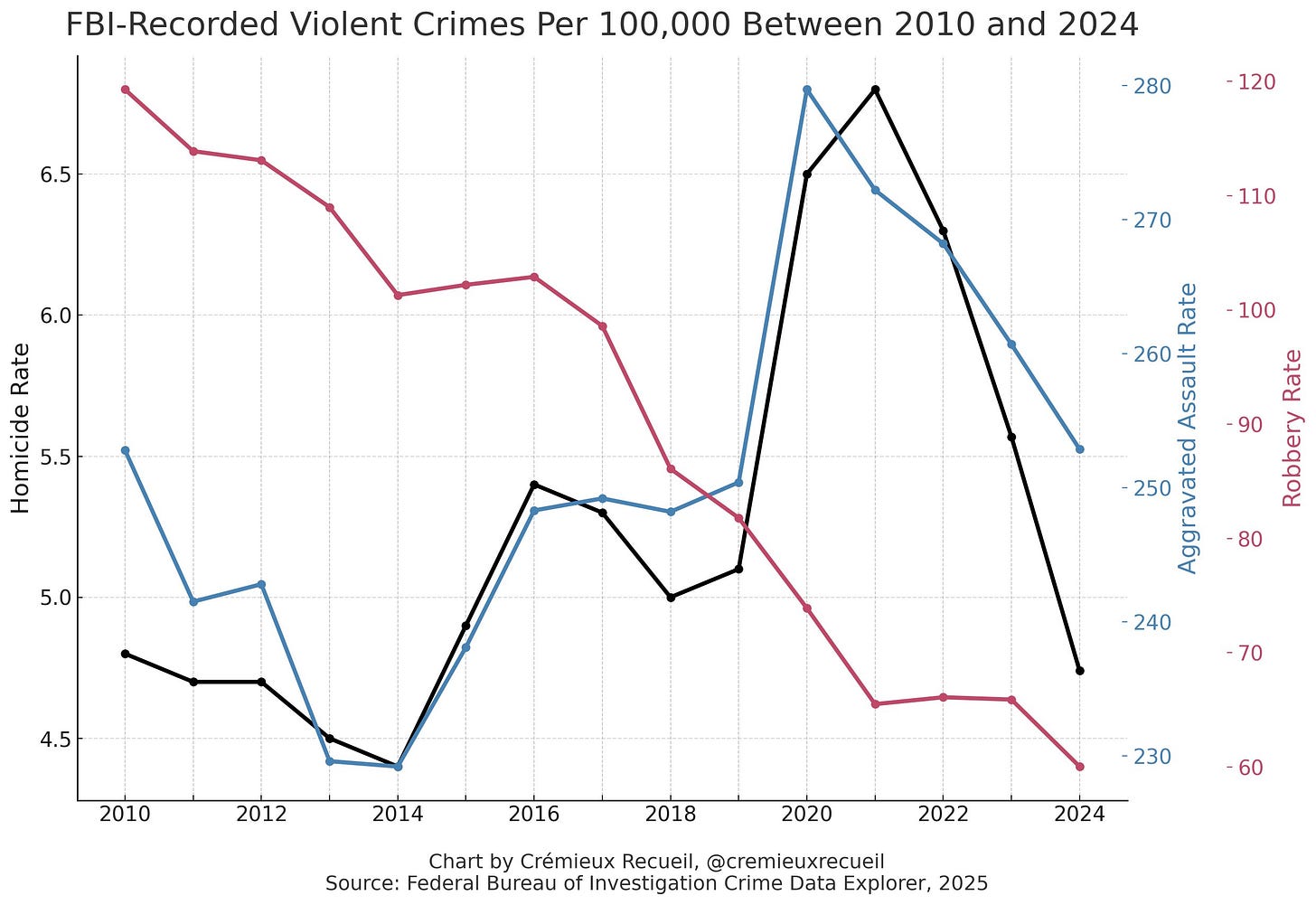

We can see the importance of such disrupting and defusing very clearly in the surges in homicides after the Ferguson and George Floyd BLM riots. Massive surges in anti-police activism led to police withdrawal, leading to fewer interruptions of confrontations, leading to surges in homicide.

Needless to say, people’s genetics—their continental ancestry—did not change during these sharp surges in homicides and serious assaults.

Given the dynamics of bravado culture, it is not surprising that African-American men are almost twice as likely as Euro-American men to see themselves as very masculine. In the US, African-American communities are regularly mis-policed (too little connection-building, too much quasi-militarisation) and under-protected (too few detectives with too little back up). Stigmatisation that obscures the under-policing easily encourages misplaced militarisation, as if dealing with hostile territory rather than fellow citizens.

Urban anthropologist Elijah Anderson analysed inner city youth attitudes as a fluctuating and overlapping tension between street (bravado) and decent (dignity) outlooks and behaviours, with the power and appeal of street culture coming from:

... the profound sense of alienation from mainstream society and its institutions felt by many poor inner-city black people, particularly the young. The code of the streets is actually a cultural adaptation to a profound lack of faith in the police and the judicial system. The police are most often seen as representing the dominant white society and not caring to protect inner-city residents. When called, they may not respond, which is one reason many residents feel they must be prepared to take extraordinary measures to defend themselves and their loved ones against those who are inclined to aggression. Lack of police accountability has in fact been incorporated into the status system: the person who is believed capable of “taking care of himself” is accorded a certain deference, which translates into a sense of physical and psychological control. Thus the street code emerges where the influence of the police ends and personal responsibility for one’s safety is felt to begin. Exacerbated by the proliferation of drugs and easy access to guns, this volatile situation results in the ability of the street oriented minority (or those who effectively “go for bad”) to dominate the public spaces.

People within the same family may manifest either orientation, or even move between them depending on circumstances.

Graduate student Alex Belkin, blogging about research for his dissertation, writes:

Another way police were illegitimate was that they were slow to respond to reported crimes. In Cleveland, for example, federal investigators found that this was the chief complaint of black residents, who accused police of corruption and racism as reasons for their belated response or indifference to intra-racial crimes. Wayne R. LaFave, in his 1965 study of arrest law and practices, quotes a black assistant prosecutor summarizing this presumption: “There is too much of a tendency on the part of police officers, juries, and even judges to dismiss Negro crimes of violence with the saying, ‘It’s only Negroes, and they’ve always been like that.’”

Under- and over-policing had a profound, tragic effect on black communities as it does today. It both provoked resentment and hostility and discouraged residents from seeking out police as arbiters of conflicts, as peacekeepers. It created a world in which a kind of extralegal street justice could thrive — where people took matters into their own hands.

African-American writer Ta-Nehisi Coates talks of how, growing up in West Baltimore, much of his mental effort was directed, every day, to minimising the risk of violence.

While policing services—through stigma, incompetence, poor strategies and, above all, inadequate social connection, trust, numbers and resources—remain not up to the task of moving African-American communities out of their high violence social equilibria, bravado culture will retain its grip.

Community tensions

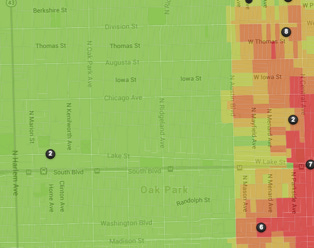

Particularly if one is raising children, living within, or adjacent to, a much higher level of violence is something to avoid. The dramatic differences in rates of violence in urban communities is sufficient, on its own, to explain “white flight” from urban communities that descendants of American slaves moved into in significant numbers. In the C19th, the spread of a racially stigmatising Confederate diaspora had led to patterns of “black flight”, encouraging residential segregation that public policies—both formal and informal—then further encouraged.

The stereotypes of violence not only inhibit seeing the wider public policy culpability for the high violence equilibria in urban African-American communities, it creates its own aggravation of inter-community relations, as it positively encourages African-American criminals to target Euro-American victims, using the stereotype of African-American (“black”) male violence to their predatory advantage. This thereby turns fears of spill-over violence into fear grounded in predatory patterns of behaviour.

A simple and straightforward model indicates how significant violence can be for the Euro-American experience of living among a high level of African-Americans. Leaving out the effects of highly disparate rates of violence creates a diverting patina of illegitimacy over “white” reactions. Such omissions also helps to burnish African-Americans as sacred victims.

High-violence communities have an increased likelihood of riots, particularly violent riots, which has, at various times, multiplied these social effects. Even with riots, culture makes a difference, as seen in the different patterns of behaviour between Afro-Caribbeans and more recent African immigrants in the 2011 UK riots.

Once your beliefs, once what-is-in-your-head, is your identity—your moral identity—you are hugely motivated to police what information you are exposed to, and the significance of information, to protect the beliefs you have turned into moral assets. Moreover, the more one has to—and is willing to—rationalise toxic untruths, the more one shows loyalty to the shared status games. A point that also applies equally to Jim Crow racists as modern “woke” Critical Constructivist left-progressives.

The “woke” path of making sacred—so not permitting any criticism of—various marginalised groups has licensed excuse-making for bad behaviour. This is counter-productive at so many levels. Having everyone being held to the same standards, while being provided with effective policing, is the path to stable pacification of high-violence localities.

Culture clashes

To those born and raised in a Western dignity culture—or the Asian equivalents—not only is the (much) higher level of violence threatening, so are the demanding-respect social cues of bravado culture. Norman Podhoretz’s 1963 essay My Negro Problem—And Ours on growing up in Brooklyn is a particularly powerful statement of the mixture of violence and threat from bravado culture. As Elijah Anderson notes of the code of the street:

For people who are unfamiliar with the code—generally people who live outside the inner city—the concern with respect in the most ordinary interactions can be frightening and incomprehensible.

This sense of threat, of fear, can extend to the police. Mixed-ancestry writer John Wood Jnr writes of how changing his hair to corn rows adversely affected how strangers interacted with him, though his “proper” English would then reverse the effect: the adverse social cue of his haircut being overridden by the positive social cue of his speech. The whole notion of “acting white” is about social (i.e. cultural) cues.

Teachers, other professionals and officials raised in a dignity culture are likely to have problems with students, adolescents and adults operating in a bravado culture. This even without considering other current and legacy effects of racialised stigma. Moreover, failure to impose order in public schools leads to a school-level bravado culture that is highly corrosive of any serious educational attainment.

There is a strong tendency, in academic and progressivist circles—if not directly discussing crime—to not to mention violence within African-American communities, especially when discussing “white” attitudes or behaviour. This is clearly intended to maintain race talk—and particularly anti-racism talk—but this pattern of omission helps build-in de facto tolerance of the much higher levels of violence in African-American urban communities; notably by using ostentatious anti-racism to direct animus towards “white” residents fleeing (unmentioned) violence and not to inadequate provision and application of police services.

A notable case of such omission is the study, led by economist Raj Chetty, on intergenerational income mobility in the US. The study engages in the standard racialized descriptions of what are clearly ethnocultural patterns. While incarceration rates do get mentioned, nowhere is the dramatic difference in rates of violence discussed, even though a key conclusion positively shouts that levels of violence might be a key factor:

…the black-white gap is significantly smaller for boys who grow up in certain neighborhoods – those with low poverty rates, low levels of racial bias among whites, and high rates of father presence among low-income blacks. Black boys who move to such areas at younger ages have significantly better outcomes, demonstrating that racial disparities can be narrowed through changes in environment.

As YouTuber Rudyard Lynch notes, Black America went from social untouchables to sacralised group in less than a generation, based on the standard left-progressive pattern of bribing a group’s elite while failing the rest. This included surging welfare to single mothers (“marrying the state”) undermining family structures while affirmative action drew the African-American middle class into Federal employment, and out of local communities—both residentially and occupationally—helping to atrophy African-American commercial life. Busing students destroyed connections between schools and communities without generating benefits to justify such disruptions.

As honour cultures in general—and bravado cultures in particular—are very much about male reputation, expectations, and behaviour, thinking in terms of moral cultures and social cues likely help explain two striking results. One is that having a Euro-American mother essentially eliminates any pattern of disadvantage for the children of an African-American father. However, this result does not occur if the mother is African-American and the father is Euro-American. The second is that African-American women have a slightly better income profile than one would predict from their parent’s incomes while African-American men have a worse one. (Both of these results contradict the intersectionalist claim that disadvantage is additive.)

If African-American women are much less likely to express bravado culture cues—at least in a way that others find threatening—and to suffer its harms, then this would help explain the latter pattern. If mothers are more important than fathers in generating moral expectations and transmitting cultural cues—including the burdens, or lack thereof, of inherited stigma—then that would do much to explain the former pattern.

A (small) study of transracial adoptions did find that the cognitive styles of African-American mothers was much less conducive to infant and child cognitive development than those of Euro-American mothers. Either way, using racial descriptors is antipathetic to grappling with these social patterns, remembering that none of us are just our continental ancestry in our behaviour.

Race fails as an explanation of the varying scale across time and space of violence in African-American communities. The path to reducing the level of violence in such communities to close to the same level as other Americans is the same path that, over time, so dramatically reduced the rates of homicide in Europe: increased state-enforced order—in the modern context, the provision of police services—willing, able and trusted to provide the level of protection (and especially homicide clearance rates) required for the patterns of dignity culture to be become entrenched. This includes building connections and trust, and encouraging local social order, so as to make confrontations less likely, less likely to get physical, less likely to become violent, and less likely to turn deadly.

There is no good form of race talk that will help achieve this. On the contrary, race talk gets in the way and, at its worst, helps perpetuate the death and violence that continue to, so unnecessarily, blight those communities.

The next post reviews Jen Ludwig’s book Unforgiving Places and discusses possible solutions.

References

Lukas Althoff and Hugo Reichardt, ‘Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery,’ Hoover Institute Working Paper 23005, June 2023. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/LRP WP 23005.pdf

Peter Arcidiacono, Andrew Beauchamp, Marie Hull, & Seth Sanders, ‘Exploring the Racial Divide in Education and the Labor Market through Evidence from Interracial Families,’ Journal of Human Capital, 9 (2), (2015) 198-238. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/econ/2

Samuel Bazzi, Andreas Ferrara, Martin Fiszbein, Thomas P. Pearson, Patrick A. Testa, ‘The Confederate Diaspora,’ Working Paper 31331, June 2023, Revised May 2025. http://www.nber.org/papers/w31331

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, Sonya R. Porter, ‘Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,’ Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Volume 135, Issue 2, May 2020, 711–783. https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/race/

O¨rjan Falk, Ma¨rta Wallinius, Sebastian Lundstro¨m, Thomas Frisell, Henrik Anckarsa¨ter, No´ra Kerekes, ‘The 1% of the population accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions,’ Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2014, 49, 559–571. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3969807/

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Pauline Grosjean, ‘A history of violence: The culture of honor and homicide in the U.S. South,’ Journal of European Economic Association, 2014, 12 (5), 1285–1316. https://www.uts.edu.au/globalassets/sites/default/files/121017.pdf

David D. Haddock and Daniel D. Poisby, ‘Understanding Riots,’ Cato Journal, Vol.14, No.1 (Spring/Summer) 1994, 47-157. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/1994/5/cj14n1-13.pdf

Tera R. Hurt, Stacey E. McElroy, Kameron J. Sheats, Antoinette M. Landor, Chalandra M. Bryant, ‘Married Black Men’s Opinions as to Why Black Women Are Disproportionately Single: A Qualitative Study,’ Personal Relationships, 2014 Mar;21(1):88-109. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4465800/

Juta Kawalerowicz, Michael Biggs, ‘Anarchy in the UK: Economic Deprivation, Social Disorganization, and Political Grievances in the London Riot of 2011,’ Social Forces, Volume 94, Issue 2, December 2015, 673–698. https://www.academia.edu/7634221/Anarchy_in_the_UK_Economic_Deprivation_Social_Disorganization_and_Political_Grievances_in_the_London_Riot_of_2011

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Glenn Loury and Rajiv Sethi, ‘Crime and Punishment in a Divided Society,’ no date. https://www.qmul.ac.uk/sef/media/econ/events/Crime-and-Punishment.pdf

Jens Ludwig, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Elsie G. J. Moore, ‘Family Socialization and The IQ Test Performance of Traditionally and Transracially Adopted Black Children,’ Developmental Psychology, (1986) 22(3), 317-326. https://www.scribd.com/document/34145069/Elsie-G-J-Moore-Family-Socialization-and-the-IQ-Test-Performance-of-Traditionally-and-Transracially-Adopted-Black-Children

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Thaddeus Russell, A Renegade History of the United States, Free Press, [2010], 2011.

Jonathan St. B.T. Evans, ‘In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning,’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.7 No.10 October 2003, 454-459. https://faculty.weber.edu/eamsel/Classes/Methods (3610)/Old Sections/Fall 2010/Fall 2010 Project/Evans (2003).pdf

Ryan Schacht, Doug Tharp, Ken R. Smith, ‘Marriage Markets and Male Mating Effort: Violence and Crime Are Elevated Where Men Are Rare,’ Human Nature, 2016 Dec;27(4):489-500. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308763261_Marriage_Markets_and_Male_Mating_Effort_Violence_and_Crime_Are_Elevated_Where_Men_Are_Rare

Rajiv Sethi, Brendan O’Flaherty, ‘Homicide in black and white,’ Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 68, Issue 3, 2010, 215-230. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094119010000343

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS January 9, 2018, Vol.115, No.2, 245–253. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1713611115

I'm working on an essay about the blatant cultural appropriation of the black intelligentsia - the fact that they seem to want to associate themselves with the struggles and experiences of poor/working class black Americans. I was planning to post it within a few hours but your essay has given me more to think about. Thank you!

https://jmpolemic.substack.com/p/white-supremacy

Excellent essay.

Race talk is certainly confusing and often counterproductive when it comes to identifying underlying causes of disorder and developing appropriate policy strategies.

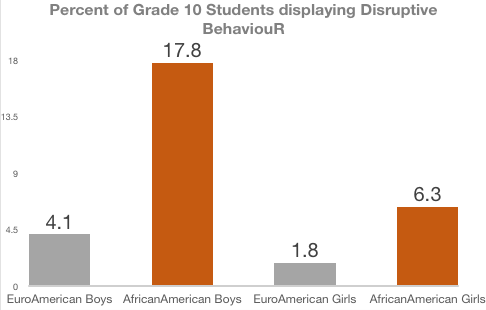

The reality is that when almost 20% of black male students in school exhibit disruptive behavior, race is a useful tool for identifying an urgent problem, even if just over 80% of black male students in the school are not acting disruptively.

I read the study you cited: the model shows that the working class white man’s family is almost 100% certain to experience violence as the proportion of blacks living in his neighborhood rises high enough.

When a mental model works this well on an issue that really matters, ie our personal safety, that mental model gets applied by all but the ignorant, the self-deluded, and fools.