Collapsing fertility is not so mysterious

Homo sapiens have never worked out how to have demographically sustainable cities at scale.

Cities are demographic sinks. That is, cities have higher death rates than fertility rates.

For much of human history, cities have been unhealthy places to live. This is no longer true: cities have higher average life expectancies than rural areas. But they are still demographic sinks, for cities collapse fertility rates.

The problem is not that more women have no children, or only one child, making it to adulthood. Such women have always existed, though their share of the population has gone up across recent decades.

The key problem is the collapse in the demographic “tail” of large families. Cities are profoundly antipathetic to large families, and have always been so. This is particularly true of apartment cities—suburbs are somewhat more amenable to large families, though not enough to make up for the urbanisation effect.

While modern cities do not have slaves and household servants who were blocked from reproducing as ancient cities did, various aspects of modern technology have fertility-suppressing effects. Cars that presume a maximum of three children, for instance. An effect that is worsened by compulsory baby car-seats. Or ticketing and accommodation that presumes two children or less. There is also the deep problems of modern online dating. Plus the effects that endocrine disrupters and falling testosterone may be having.

These effects also extend to rural populations: falling fertility in rural populations is far more of a mystery than falling fertility in urban populations. How much declining metabolic health plays in all this is unclear. Indeed, futurist Samo Burja is correct, we do not really understand the “social technology” of human breeding.

Be that as it may, cities as demographic sinks is a continuation of patterns that go back to the first cities.

Matters at the margin

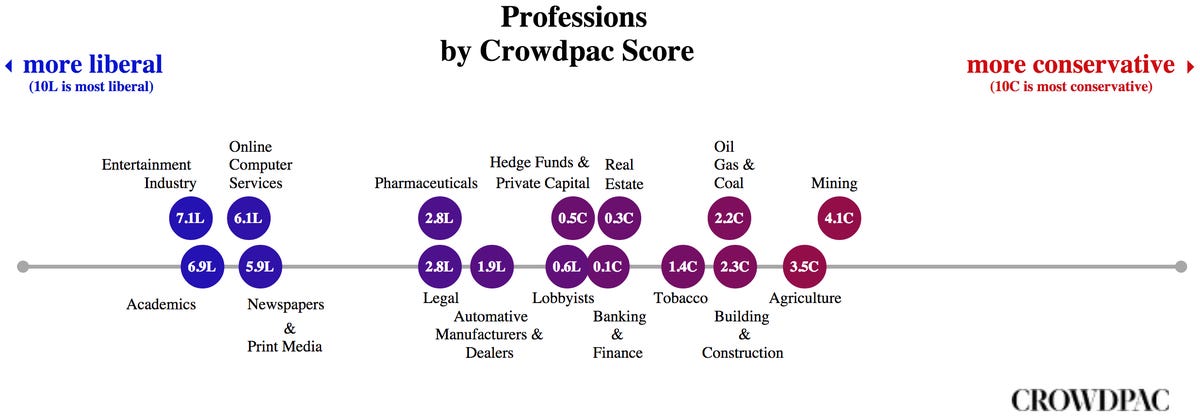

There are factors at the margin known to make a difference. Religious folk breed more than secular folk, though that is in part because rural people are more religious and city folk more secular.

Educating women reduces fertility. This is, in part, an urbanisation effect, as more education is available in cities. It is also an opportunity cost effect—there is more to do in cities, both paid and unpaid.

Education increases the general opportunity cost of motherhood, by expanding women’s opportunities. This also makes moving to cities more attractive. Women having more career opportunities reduces the relative attractiveness of men as marriage partners, reducing the marriage rate.

Strong cultural barriers against children outside marriage can reduce the fertility rate, by largely restricting motherhood to married women. This makes the fertility rate more dependant on the marriage rate.

Educating women makes children more expensive, as educated mothers have educated children. Part of the patterns that economist Gary Becker analysed.

Civilising tends to be liberalising

Cities are human-created environment—and human-created environments at scale—so have more things humans like to do. This makes cities attractive places to live. It also gives them a liberalising effect, as people move from the fear/caution/constraint realities of rural life to the human-created possibilities of city life.

That civilisation in general increases human-created possibilities means that the expanding capacities of civilisation has a liberalising effect over time. Cities concentrate this effect, leading to increasing questioning of the founding ideas of the civilisation, which arose in very different circumstances. This is all nicely discussed here.

Cities are famously hubs of creativity. Not all creativity is, however, good creativity. That cities can be sources of ideas that undermine the basis of a civilisation easily extends to, or includes, ideas that are actively toxic. The sense of escape from past constraints that cities generate particularly intensely can lead to idealisation of imagined futures, and all the problems that generates.

Transitory transitions

Nevertheless, the big demographic story remains that cities are profoundly antipathetic to large families, and humans cannot manage population growth—or even population stability—without a sufficient “tail” of large families.

That cities are inherently demographic sinks was somewhat obscured during the industrial age demographic transition, when unanticipated collapse in infant and child mortality led to dramatic increases in population. The postwar WWII baby boom—whose causes remain a mystery—obscured this further. Once it passed, the normal pattern of cities being demographic sinks re-asserted itself.

Much of what has been going on is a massive population shift from the countryside to the cities. The larger the proportion of the population living in cities, the more the pattern of cities being demographic sinks dominates fertility rates. As futurist Samo Burja notes, it is not at all clear that mass production is compatible with mass reproduction. Indeed, if the former means urbanisation at sufficient scale, it is not.

The first folk whose civilisation substantially urbanised were the Sumerians. They developed a pattern of populations living in the cities, where they could be protected, and walking out to the surrounding fields. The Sumerians were also the first civilisation to suffer internal fertility collapses—cities as demographic sinks aggravated by irrigation leading to increased salinisation.

No civilisation since has solved the problem of cities being demographic sinks. Cities have always relied on inflows of rural populations to sustain themselves. Whenever rural populations stopped moving to cities, the population of those cities collapsed.

Labour mobility and the Black Death

The need of cities to have population inflows had a great deal to do with why C14th Europe’s reaction to the Black Death (1346-1353) was so unusual. Normally, a dramatic increase in the labour scarcity value—whether from a dramatic drop in population or a dramatic expansion in available land or both—leads to an increase in labour bondage, as elites impose serfdom or import slaves to extract the labour scarcity premium.

This was why Africa was the continent of slavery—being where Homo sapiens evolved it was full of parasites, pathogens, predators and mega-herbivores who co-evolved with, and could cope with, Homo sapiens, keeping human population densities down. Hence, across Sub-Saharan Africa, for millennia, labour was more valuable than land.

Labour becoming more valuable than land is why the Americas became continents of slavery. The importing of the entire Eurasian disease pool all at once led to a dramatic—indeed horrifying—population collapse. So the European colonisers imported slaves into the Americas purchased from the continent of slavery (Africa). Almost none of the enslaving was done by Europeans. First, the Africans were already enslaving each other, with African states generally being slave states. Second, the life expectancy of a European adult away from the coast in tropical Africa was about a year.

Labour becoming more valuable than land is why, after the Antonine (165-180) and Cyprian (c.249-c.270) plagues, coloni (Roman serfdom) developed in the Western Roman Empire. It is why, after the Justinian plagues (541-549, but extending to 767), serfdom developed in early medieval Europe. It is why, after gunpowder weapons enabled the clearing away of pastoralist raiders, plus the development of the Atlantic economy—more ships, more barges, more canals—increased the market for Eastern European grain, across Eastern Europe, those who had been free peasants were enserfed. This most famously happened in Russia, but also occurred in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in Prussia and the Habsburg lands.

Again and again, when labour was more valuable than land, mass labour bondage arose. Serfdom was sufficient if the population was in situ, so that merely blocking labour mobility was enough—i.e., no leaving the estate without the landlord’s permission. Slavery—or sometimes indentured labour for populations not permitted to be enslaved—was the response if labour had to be imported.

Yet we do not see mass labour bondage after the Black Death in Western Europe. The mercantile cities needed labour mobility to replenish themselves after the massive plague die-off. Their taxes and loans were sufficiently important to monarchs that rulers failed to provide the needed enforcement for landlord cartels to (re-impose) serfdom. This meant that—unusually before the modern era—labour benefited significantly from its increased scarcity. It also increased the already existing propensity to invest in machinery to increase the productivity of (expensive) labour.

Collapsing civilisation

Collapse in terms of human societies is a much contested concept. A useful definition is provided by archaeologist Glenn Schwartz:

In the archaeological literature, collapse usually entails some or all of the following: the fragmentation of states into smaller political entities; the partial abandonment or complete desertion of urban centers, along with the loss or depletion of their centralizing functions; the breakdown of regional economic systems; and the failure of civilizational ideologies.

Archaeologist Guy D Middleton provides an enlightening discussion of the complexities of collapse in human history while his discussion of the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Aegean highlights the problems of evidence.

We are currently doing two things that historically led to collapses of civilisational orders:

becoming so urbanised that fertility collapses; and

systematically wearing away the topsoil that grows our food [though see the discussion in the comments with Ron M].

The latter is one of the many, many reasons the plant food push is so dysfunctional. Industrial monoculture wearing away the topsoil we rely on is a classic civilisational-collapse pattern. Using more and more fertiliser to compensate at best ameliorates the effect, it does not stop it. Yes, you only lose a bit of topsoil each year. But if you lose a bit, year after year after year, at some stage you do not have enough soil left to sustain the agriculture the population has been living off. Population collapse and/or dispersal then follows.

We are also doing other things that undermine civilisation:

metastasising bureaucracy becoming increasingly dysfunctional;

undermining competence via affirmative action and diversity hiring leading to the collapse of complex systems;

undermining social solidarity, leading to more distrust and alienation;

using shaming and shunning via social media to create dysfunctional public discourse;

having dysfunctional education systems pumping toxic ideas into discourse and institutions,

not grappling with the level of evolutionary novelty let loose by technology, ...

Nevertheless, we are doing two big things that we know have collapsed civilisations.

The knowledge that we are doing so is not hard to find. The institutional functionality to notice—and also do something effective about it—that is a different matter.

After all, a plausible explanation for The Great Silence is that advanced technology pushes species beyond the limits of their evolved adaptations. As Samo Burja says:

We're on a timer to reinvent social technology that causes us to breed or we will go extinct. [47:05]

ADDENDA. Economist Bryan Caplan suggests that educating women lowers the fertility rate by delaying child-bearing, as the older women start having children, the less children they have.

There is also evidence that city life raises IQ, as second generation migrants who have moved to Western cities have higher average IQ than their parents. (There may be something to Marx and Engel’s complaint about the idiocy of rural life: though it is possible they meant the isolation of rural life.) I wonder if recent falls in IQ might, at least in part be a result of decreasing metabolic health, remembering that genes are a recipe not a mold.

References

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Jean Gimpel, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages, Pimlico, [1976] 1992.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Jane Jacobs, The Economy of Cities: The Life and Death of Great American Cities, Vintage Books, [1969] 1970.

David R. Montgomery, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilization, University of California Press, [2007] 2012.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Very good!

A couple of (admittedly minor) points:

- modern women have their lives back to front. Their bodies are best capable of having children in their late teens/early twenties, and the best paying years for careers are mid thirties through forties. But they are normally studying/working in their teens/twenties and not looking at children until they reach 30; bad for both their bodies and their bank balances.

- the development of serfdom also marks the end of large scale slavery in Europe. While the coloni lost rights, former slaves gained some.

Despite these quibbles, excellent article.

While not a fan of the Chicago school of economics (wherein all social phenomena have an economic explanation), I do think there is a transition point on fertility - when children flip from being assets to liabilities. This might be most obvious in urban settings, given the cost of living differential with suburbs and rural, but also keyed on the expectations of parents for the future of their children. Traditions die in cities, so the expectation for children to carry on those traditions would as well and be replaced with expectations for social mobility (climbing).