Downward Resilience: Adverse incentives within the medieval Roman state

States and surplus; empires and trade; fiefs and vassals; and the pathologies of bureaucracy.

The survival of the Eastern Roman state for almost a thousand years after the fall of the Western Empire is a remarkable story of resilience. Nevertheless, compared to the major kingdoms of the Latin West, it is a path of downward, rather than upward, resilience. This is particularly so from the later C11th onwards.

This paper does not use the terms Byzantine or Byzantium. First, because it is anachronistic. Everyone at the time, including themselves, referred to them as Romans. Instead, it uses medieval Roman. With Late Roman referring to the period of the Dominate (284-641).

Second, because the terms Byzantine and Byzantium are misleading. We are dealing with a medieval Christian state that had a quite different institutional trajectory than other medieval Christian states because it was Roman.

It could be that the institutional differences between Greek and Latin Christianity generated the key differences. The Latin Church operated across jurisdictions with an internally chosen head able to assert himself against temporal rulers. The Greek Church operated within the Roman state, with the Patriarch being somewhat subordinate to the Emperor. This was a model that was later adopted in post-medieval Protestant Europe. The differences in institutional development between Protestant and Catholic Europe were sufficiently limited to suggest that differences in Church governance have very limited explanatory power.

Instead, it was the evolution of late Roman institutional patterns that generated what became an institutional path of downward resilience.

Malthus and meritocracy

Prior to the creation of mass prosperity, beginning with the application of steam power to transport via railways and steamships in the 1820s, most humans lived subsistence, or near-subsistence lives, subject to Malthusian dynamics. That is, population was limited by the food supply.

The invention of farming around 11,000 years ago did not mean significant creation of surplus (production above subsistence). More food mostly meant more babies. Indeed, farming niches tended to be smaller than foraging niches, which increased farming’s demographic advantage over foraging. (A niche being a position within an ecology that enables an organism to survive and potentially reproduce.)1

To have significant creation of surplus requires food to be (1) extracted before it can be turned into more babies which then requires (2) stored food, so seasonal crops. Hence, states have dominated the extraction of surplus across history. Even in our mass-surplus societies, the profit share of GDP (excluding housing and financial institutions) is 15-20 per cent, while the tax share in developed democracies is around 25-50 per cent of GDP.

As states pacify in order to extract revenue, the resultant social peace tends to generate population increase greater than any expansion in arable land or productive technology. Over time, this creates both shrinking niches and intensified competition for existing niches.

At the top of society, more surviving elite children mean intensified competition for elite niches, which can lead to intense civil strife.

At the bottom, the shrinking of niches due to population pressure means the tax burden becomes more onerous, even if taxes are held constant, with more folk being pushed into the underclass. That leads, over time, to more banditry and more peasant revolts.

If a society is polygynous, so women are distributed socially upwards, this tends to generate a non-breeding underclass, aggravating the banditry and peasant revolt effects, and more elite children, aggravating the elite-competition effect. Pastoralist empires, with their polygynous elites and constrained grazing land, tended to suffer particularly intense elite-competition problems.

Due to our highly cooperative reproduction and subsistence strategies, based on transferring risks away from child-rearing and resources to child-rearing, Homo sapiens have been selected to both be normative and to be able to game norms.

When a group faces strong external pressures, there tends to be selection for group cohesion, for norm-adherence and prosocial behaviours, as strong character tests are somewhat “built in”. As external pressure relaxes, and competition becomes more internal, there tends to be selection for the ability to game norms, favouring manipulative personalities, while character tests weaken or vanish.

This is the evolutionary context for Ibn Khaldun’s analysis of harsh environments creating strong asabiyya (group feeling) that enables pastoralists to conquer farmers, with the ruling elite’s asabiyya weakening over time due to sedentary prosperity.

If one has a meritocratic officialdom, that selects for capacity (intelligence, executive function) but not character, over time more morally disordered personalities, i.e., the more uninhibited and manipulative, will tend to be selected for within officialdom. This will lead to more morally-disordered decision-making, undermining norm adherence.

More sociopathic decision-making by officials, intensified elite competition over resources, expanding banditry and peasant revolts. This is the late Chinese dynastic cycle. China, due to its elite polygyny and its geographically constrained population density creating periodic unifications, goes through these patterns particularly intensely.

Note that these patterns play out over centuries. They are slow “boiling frog” phenomena. It takes two to three centuries for a major Chinese dynasty to go through the entire cycle: Song 960-1279, Ming 1368-1644, Qing 1644-1912. This paper is about such “slow drip” phenomena.

It is also a paper about Eurasian, not just European, medievalism. (It’s not global, as there is no reference to the Americas or the Antipodes.)

Patterns of bureaucracy

Bureaucracy tends to be ubiquitous, because any administrative role can be turned into a set of tasks and processes. Bureaucracy also comes with some standard pathologies:

A tendency to hoard authority, particularly by delegitimising alternative sources of information.

A preference for spending resources on itself (unlike commerce, which tends to select for efficiency, as releasing un- or under-used resources generates income).

Seeking protection from the complexities of competence (that is, limit accountability for outcomes). This is aided by it being often hard to accurately judge the net effect of bureaucracy, including the effects of doing things bureaucratically. Hence the default is to be judged by intention and by attention to process.

Effective public goods, including good laws, can systematically reduce transaction friction (the rate at which transaction costs slow down transacting). Transaction costs are: costs entailed in making an exchange or other interaction. Specifically, search and information costs; bargaining and decision costs; policing and enforcement costs.

As part of hoarding authority and increasing resources spent on themselves, it is often in the interest of bureaucracies to increase transaction friction. Especially as the more official discretions there are, the greater the capacity for corruption. (Corruption being the market for official discretions.)

It is hard for folk living in common law, or civil law, developed democracies to realise how dysfunctional regulatory and bureaucratic structures can be. A famous social experiment conducted in Peru documented such dysfunction:

Our goal was to create a new perfectly legal business. The team began filling out the forms, standing in the queues and making the bus trips into central Lima to get all the certifications required to operate, according to the letter of the law, a small business in Peru. They spent six hours a day on it and finally registered the business — 289 days later. Although the garment worship was geared to operating only one worker, the cost of legal registration was $1,231 — thirty-one times the monthly minimum wage.

(Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital, p.15.)

Latin America is poorer and more corrupt than Anglo-America because in the former the state is set up to generate high levels of transaction friction and in the latter it is not.

As states dominate the creation (via extraction) and deployment of surplus, they are a fundamental structuring element of their polities. They are not some “reflection” of the underlying society. Especially as, historically, it was far more common for states to be imposed on a society than originate from them.

This paper is particularly concerned with the pathologies of bureaucracy, but there were reasons why the medieval Roman state remained more highly bureaucratised than other contemporary states:

… the East Roman empire up to the twelfth century was well served by an efficient—indeed, ruthless—fiscal and logistical system which, by maximizing the often limited resources at the state’s disposal, gave the imperial armies an advantage which on occasion meant the difference between success and failure, and certainly facilitated the survival of both the military and civil administration of the empire in times of adversity.

(John Haldon, Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204, p.139)

The experience of food, fodder and so forth turning up at the right place in the right time would reinforce a sense of the utility of the bureaucracy.

Thus, the dilemma of bureaucracy is that it is both useful and has pathologies. If it was just useful, there would be no problem. If it was just pathological, no one would use it. Moreover, the balance between the two can and does shift, both over time and across functions.

A key feature that distinguishes the Late Roman Dominate from the Early Empire Principate is a massive growth in government bureaucracy:

Under Diocletian’s rule the rate of increase of government was hugely accelerated. Increase continued more slowly over the next century or so. Impossible though any exact census of the administration must remain, still, it is safe that the roughly three hundred career civil servants in the reign of Caracella (a. 211-217) had become thirty to thirty-five thousand at any given time in the later empire, a change attributable in the greater part to Diocletian.

(Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, p.83)

The massive expansion in bureaucracy led to a distinctly lower level of education and cultural attainment among officials. It also meant, without increased capacity to extract surplus to match the increased administrative costs, that less surplus was available for other purposes, hence a less capable state.

The sense one gets that the Late Roman state is a less capable state than the Late Republic and Early Empire is quite correct.

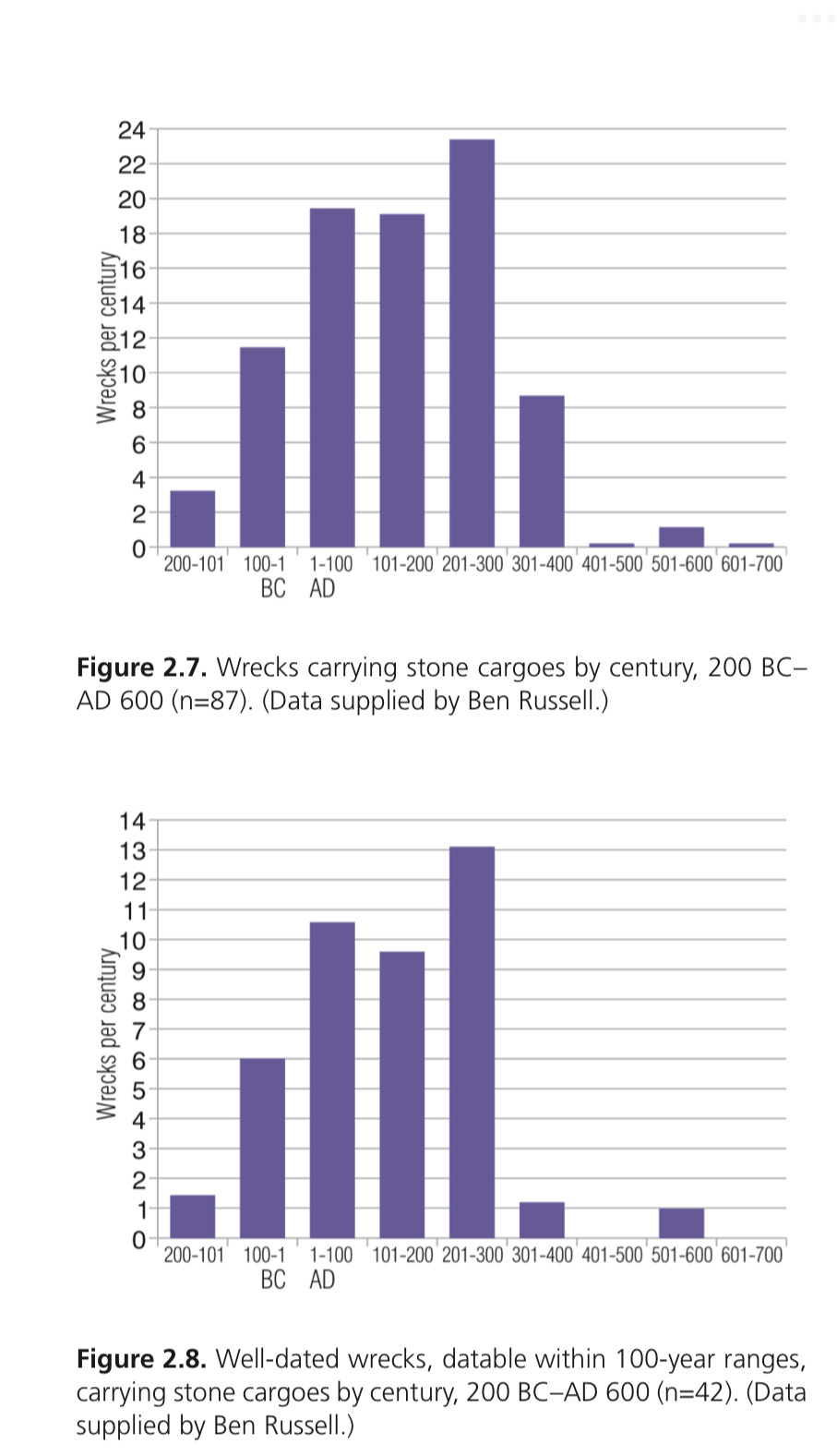

The ability of the Roman state to provide public goods has a clear tendency to deteriorate over time. Perhaps the most striking manifestation of this is that, from the beginnings of the Dominate onwards, the massive increase in bureaucracy, and reduction in commerce, coincides with a decrease in road maintenance. Localities become both less willing, and less able, to keep up the roads.

[For a discussion of why these graphs may not show what they appear to show, see here.]

The combination of pandemics and massive bureaucratisation helps explain the success of Christianity under the Dominate:

the undermining of civic self-government via much more intrusive central bureaucracy discouraged local notables from investing in local pagan festivals,

the horrors of repeated pandemics advantaged a congregational transcendent salvation religion over an immanent, this-world fertility and success religiosity, and

Christianity provided a common belief system to coordinate a much larger bureaucracy.

Trade and empire

A simple model of the importance of trade to the size and scale to pre-industrial states, where land (farming and mining) and trade are the available revenue sources for states, can usefully elucidate historical patterns in the rise and decline of empires. The model consists of three elements:

Revenue from land increases linearly: twice as much land of a given quality generates twice as much tax revenue.

Administrative (including extraction) costs display increasing returns to scale: twice as much territory takes more than twice the administrative costs to administer. This is a result of coordination costs—including communication, transport, information-management and other complexity costs—increasing with distance and scale.

Over various ranges, tax revenue from trade can generate increasing returns to scale, through provision of public goods boosting trade (safer trade routes, protected marketplaces, better adjudication), and from increasing the productivity of land from increased specialisation.

A medieval example of increasing trade through better provision of public goods is Edward I pacifying Wales by having protected marketplaces next to the castles he constructed.

The implication of (1) and (2) is that, in the absence of trade, states (“taxing jurisdictions”) will tend to be small, as the ability to allocate resources to control territory will deteriorate quicker the larger the area one is attempting to control.

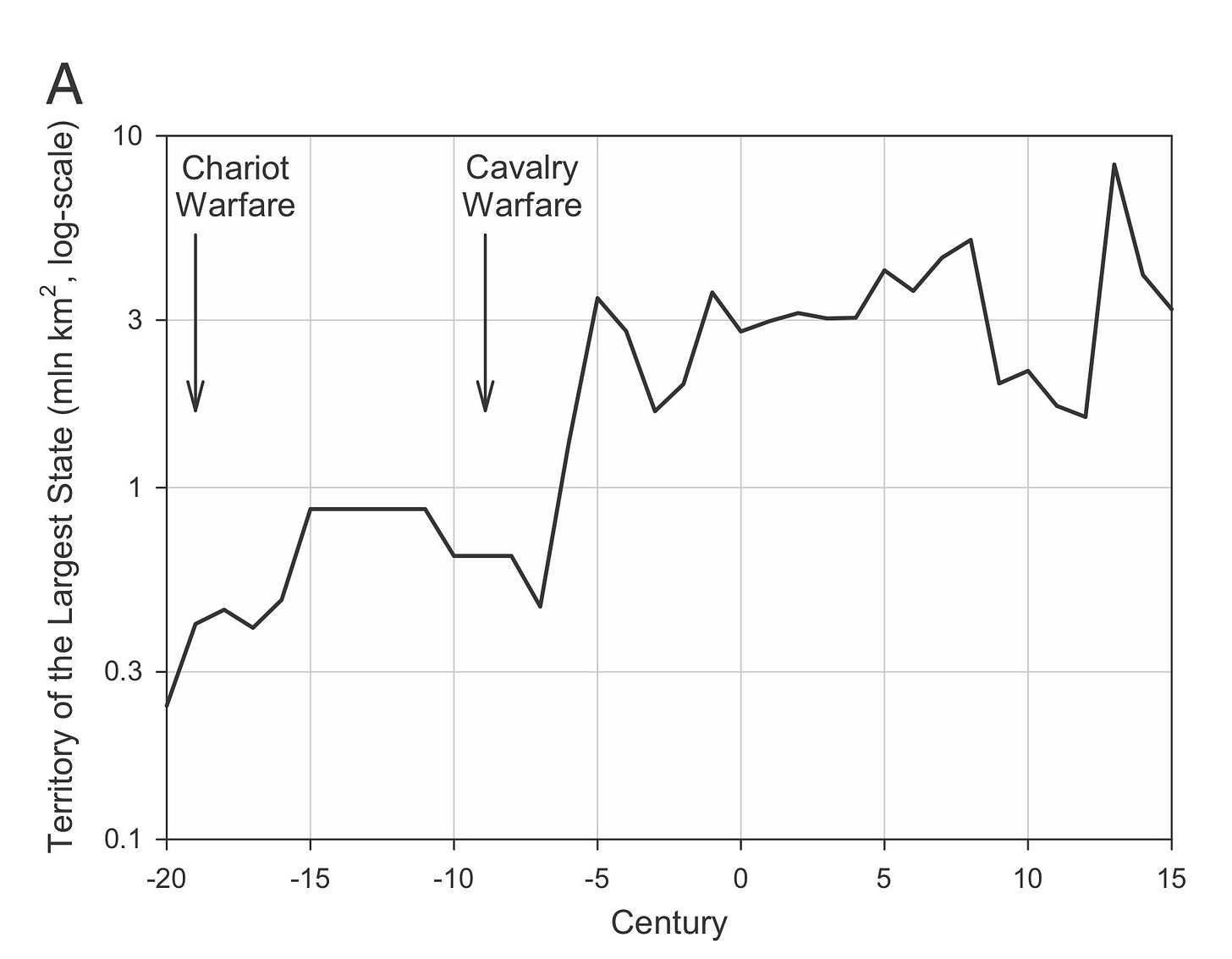

The implication of (1), (2) and (3) is that the territorial extent of states will be strongly correlated with the extent of trade. With some reinforcing feedback: more trade means larger empires, larger empires means more trade.

Across Eurasian history, the territorial extent of states is strongly correlated with the level of trade.

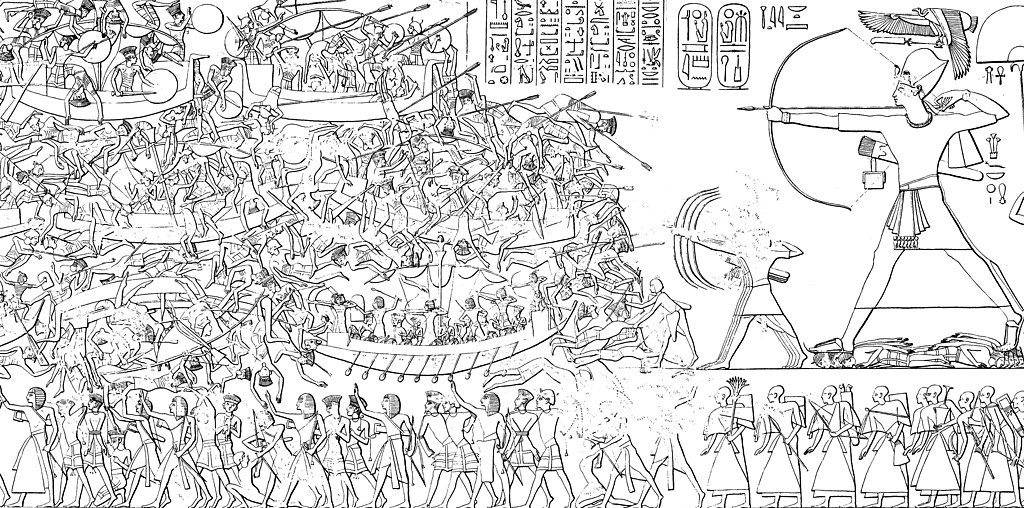

As far back as the Late Bronze Age collapse (c.1150-1200 BC), despite Rameses III’s (r.1186-1155) defeat of the Sea Peoples (c.1175BC), the collapse and disappearance of New Kingdom Egypt’s trading partners led to the decline and collapse of New Kingdom Egypt (c.1069BC), with the disappearance of the revenue “cream” the Pharaonic state relied on—the first recorded strike in history was the workers on Rameses III’s tomb downing tools because they had not been paid.

The first farming mega-empire2 (what becomes the Achaemenid Empire) arises after the Scythian empire unifies the steppes for the first time, having developed the military use of the composite recurve bow that made chariots obsolete. Pastoralists are active traders and pastoralist empires promote trade, while the steppes (relatively easy to traverse compared to mountain ranges and deserts) were key trade-routes for centuries.

The pattern of the rise and decline of empires in Eurasia from the C3rd BC Qin unification of China onwards tracks closely the (internal) patterns of Chinese unification. When China is unified, so generates more trade, there are more and larger empires across Eurasia. When China dis-unifies, so generates much less trade, we see patterns of imperial retreat and collapse across Eurasia.

The Crisis of the Third Century follows the collapse of Roman silver mining and is a generalised crises across Afro-Eurasia that sees empires collapse (Han dynasty), be overthrown (Parthian) or retreat (Kushan). Rome is able to (narrowly) survive because it retains control over the Mediterranean trade hub.

The elements of the model apply particularly strongly when:

transport costs are high (limiting the geographical size of markets and restricting long-distance to high-value goods along specific trade routes),

the capacity of states to acquire and use information was low (so diseconomies of scale in administration were high) and

most states were autocratic or, where they were not, operated to benefit a relatively narrow group (so being able to apply effective coercion was the dominant factor in state size), while

linguistic and other diversity among subjects imposed few costs, especially if local elites could be sufficiently co-opted.

Once there is the mass application of steam-generating energy sources to transport and communications from the 1820s onwards, there is increased taxing of the (increasingly transparent to the state) coordination of factors of production in factories and firms, especially via taxes on labour income.

At first, the 1820s onwards dramatic fall in transport and communication costs leads to an increase in the territorial extent of empires—notably, in the “scramble for Africa” while the British and French Empires reach their largest extent in the interwar period. Over time, however, the increased coordination of almost everything (including mobilising of national identities) from falling communication costs (including rising literacy) raises the benefits of mono-lingual over multi-lingual states. This came to have an anti (territorial) imperial effect.

More recent scholarly literature on the size of states tends to focus on contemporary conditions of dramatic falls in communication, information and transport costs, leading to mass trade, mass politics and far more socially pervasive and active states.

Vassalage as franchised rulership

Bureaucracy is, however, far from the only available mechanism for social coordination and control.

While vassalage is often thought of as quintessentially medieval, it is a very old pattern. Tributary states can be reasonably considered vassals and powerful rulers were forcing weaker rulers into tributary status as far back as the first chiefdoms.

The first polity to use vassalage as a systematic system of rule seems to have been the Scythian empire, the first major steppe-pastoralist empire. The great advantage of vassalage is that it economises on administrative costs. Rather than relying on a stream of information and orders to and from officials, rulership is structured through the relationship between overlord and subordinate ruler, with a clear set of mutual obligations and expectations.

The Scythians were not a literate people and and while they did have a few cities on the fringes of the steppes, they were were attempting to rule across vast distances where (mobile) herds were the main productive asset. They had an urgent need to minimise administrative costs. Vassalage was a much more rational form of rule for them than any bureaucratised structure.

Development of fiefs (the warrior franchise)

It also appears that the Scythians, after their conquest of the Median city-states c.650BC, were the first polity to introduce a fief system.

A pastoralist people conquers farmers, seeks to extract income from them, has no interest in becoming farmers, and needs to economise on administrative costs.

In such circumstances, granting land to a Scythian warrior, and so income from the farmers on that land, in return for military service is the obvious measure. Especially as, unlike with infantry, there were very little in the way of economies of scale in training and equipping mounted armoured warriors. The fief, the warrior franchise, becomes a localised version of vassalage, of the rulership franchise.

The next polity clearly based on a systematic vassalage-and-fief system is the Parthian empire established in the C3rdBC. Again, a pastoralist people conquers farmers, has no interest in taking up farming, wishes to extract income from farmers while economising on administrative costs. So, gentry horse archers and noble cataphracts provide the core military forces. The Sassanian dynasty (224-651) used the same system, replacing horse archers with more mounted armoured lancers.

The first dynasty within Islam to begin to use a warrior fief system on any scale is the Buyid dynasty (934-1062): an Iranian dynasty that specifically invoked their Persian heritage. The warrior fief pattern becomes systematic within Middle Eastern Islam after the Seljuk Turk (1034-1194) conquests: a pastoralist people conquering farmers and seeking to extract income from them to support mounted, armoured warriors.

Why franchises?

Both vassalage and fiefs are ways of minimising administrative costs. In particular, they avoid having to collect revenue and then dole it out again. The vassal and the fief holder do that directly themselves. The fief holders also pay to equip themselves and the training of the next generation of mounted warriors.

In both cases, it is a relationship that can be structured by an implicit or explicit contract. Especially a contract sworn by a (public) oath; oaths being typically key features of non-literate, or low-literacy, cultures.

You don’t get a choice in who to swear allegiance to (vassal), nor service to (fief). You don’t get a choice in the terms of the vassalage or the warrior service. But you do have an explicit or implicit contract that you swear to uphold.

The most explicit version of contractual allegiance I am aware of is the oath of allegiance of the Kingdom of Aragon:

We, who are as good as you, swear to you, who are no better than we, to accept you as our king and sovereign lord, provided you observe all our liberties and laws; but if not, not.

(J.H. Elliott, Imperial Spain 1469-1716, p.18)

What sort of contract gives you no choice of partner, nor of contents, but is still a contract? A franchise contract. If you are a McDonalds franchise, you cannot become a Pizza Hut or a Hungry Jacks or a Burger King. You do not have any say in the terms of the contract. But the franchise is still based on a contract.

Hence, vassalage is franchised (sub)rulership. A fief is a (mounted) warrior franchise.

Fiefs were compatible with almost any property system. From freehold, where military service was a form of tax-in-kind-via-service, to the fief-holder’s landholding being completely conditional on the service, as in Russian dvorianstvo service nobility.

Fiefs did not need to involve any land ownership at all. The tax-fiefs of Islam (iqta, timar, jagirs, tuyuls) and of the Palaiologoi medieval Roman state (pronoia) gave tax collection rights in return for (typically) military service. A tax fief could be any set revenue source, including a particular piece of land (most commonly) or a particular number of peasants.

They were not land grants in the landowning property sense. In the case of Islam, making fiefs landed property would make them subject to Sharia inheritance laws. Sharia requires property to be divided (albeit unequally) among all a father’s children.

The point of fiefs, of the mounted-warrior franchise, was to provide enough income to support at least one mounted (usually armoured) warrior. Making them land ownership grants subject to Sharia inheritance rules would lead them to becoming too small to support a mounted warrior within a single generation.

So, there were (sub)rulership franchises (vassals) and warrior franchises (fiefs) for exactly the same reason we have corporate franchises now. Vassalage and fiefs both economise on administrative costs while structuring the interaction and allocating liability and risks.

The control advantage of tax fiefs is through being a revocable act of the ruler. The social disadvantage of tax fiefs is that the holder has much less incentive to foster the productivity of the land, or develop stably productive relationships with the farmers, than do holders of land fiefs, particularly inheritable land fiefs.

That land fiefs are far more conducive to economic development via stable relationships with farmers than are tax fiefs is seen by the comments of Muslim traveller and chronicler Ibn Jubayr (1144-1217):

Upon leaving Tibnin (near Tyre), we passed through an unbroken skein of farms and villages whose lands were efficiently cultivated. The inhabitants were all Muslims, but they live in comfort with the Franj—may God preserve us from temptation! Their dwellings belong to them and all their property is unmolested. All the regions controlled by the Franj in Syria are subject to this same system: the landed domains, villages, and farms have remained in the hands of the Muslims. Now, doubt invests the heart of a great number of these men when they compare their lot to that of their brothers living in Muslim territory. Indeed, the latter suffer from the injustice of their coreligionists, whereas the Franj act with equity.

(Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, p.263.)

The difference, across centuries, between a warrior elite with a strong, multi-generational, interest in economically developing their landholdings and a warrior elite that lacks such incentives, helped put these adjacent civilisations on very different historical paths.

Narrow over broad dynasticism

The medieval Roman state was more wracked by elite usurpation rebellions, and more successful usurpations, than the major states of Latin Christendom. A pattern that goes back to the Roman Empire from the Year of Four Emperors (69) onwards.

In the medieval Roman state, 20 emperors were murdered, or probably (D) murdered, between 600 and 1204: Phocas (610), Constans II (668), Mezezius (669), Justinian II (711), Leontios (705), Tiberios IIII (705), Anastasios II (718), Constantine VI (797), Leo V the Armenian (820), Michael IIII the Drunkard (867), Constantine VII (959)D, Romanos II (963)D, Nikephoros II Phokas (969), John I Tzimiskes (976)D, Romanos III Argyros (1034)D, Romanos IV Diogenes (1072), Alexios II Komnenos (1183), Andronikos I Komnenos (1185), Alexios IV Angelos (1204), Nikolaos Kanabos (1204).

The enduring problem was that the dynastic principle was limited to the imperial throne itself. The dynastic principle is easier to maintain the more power-holders that are beholden to it.

The contrast between the stability of dynastic rule in Latin kingdoms, and in Japan,3 where there were systems of dynastic power-holders within the realm, with the level of dynastic instability within Rome, Islam and China, where this was much less true, is striking. In the case of Islam in particular, having polygynous rulers aggravated the problem, generating recurrent civil strife within dynasties.

The second ‘weakness’ of the Arabs, not unrelated to the first, was their inability to build stable institutions. The Franj succeeded in creating genuine state structures as soon as they arrived in the Middle East. In Jerusalem rulers generally succeeded one another without serious clashes; a council of the kingdom exercised effective control over the policy of the monarch, and the clergy had a recognized role in the workings of power. Nothing of the sort existed in the Muslim states. Every monarchy was threatened by the death of its monarch, and every transmission of power provoked civil war.

(Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, p.262.)

The dynastic instability within the medieval Roman state led to recurring suspicion of provincial commands. There was a recurring tendency to undermine provincial power so as to maintain central control, aiding the tendency of the central bureaucracy to hoard authority. Access to central power was thus the overwhelmingly dominant political game, increasing the appeal of usurpation, while also tending to increase the level of provincial dissatisfaction available to be mobilised.

Having a long-lasting dynasty is not, itself, a protection against civil strife, as the Wars of the Roses in England, the various periods of civil war in Japan and the civil wars within the Palaiologoi dynasty in the C14th displayed. But the confinement of the dynastic principle to the rulership itself added an extra layer of instability.

Fiefs versus militia systems

There were precursors to allocating land to support military forces directly. The Mesopotamian states at the time of the Scythian conquest of Media had a long history of “spearman land”, “archer land” etc. But such seem to have been land-grant militia systems.

The problem with militia systems is that the need to farm restricts the time the soldier can spend training or away from the land and undermines the incentive to invest in training and equipment. Thus, militia systems that are not under continual military pressure tend to degenerate, sometimes quite rapidly.

It is notable that, as the medieval Roman empire expanded under a series of warrior-emperors from the accession of Basil I in 867 onwards, and with increased investment in the central tagmata forces and in frontier defences, the quality of the thematic (militia) forces of the central provinces deteriorated quite rapidly. This further encouraged reliance on centrally-funded (i.e. the tagmata) military forces.

Conversely, a warrior fief does not require the fief-holder to spend any time farming, or supervising farming. Fief systems proved capable of providing effective mounted warriors across centuries. Notable examples include: the Iranian plateau, 220BC to 650; France: c.800 to c.1440; Iraq from 930s to 1850s; Iran from 930s to 1907; Egypt c.1000 to 1811; Japan 1185-1871.

The incentive for a fief-holder is to invest in military capacity, because that is the path to status, standing, access to power, even beyond the ability to protect what you have. The same applies for your son(s).

As a Muslim observer of the Crusader kingdoms (Usamah ibn Munqidh) observed:

… all pre-eminence belongs to the horseman. They are in truth the only men who count. Theirs it is to give counsel; theirs to render justice.

(Marc Bloch, Feudal Society: Volume 2 - Social Classes and Political Organization, p.291)

Militia systems tend not to persist: the thematic militia cavalry, operating from the later C7th to the mid C11th, was an unusually persistent system. It was even more unusual in being a cavalry militia: militia systems were usually for infantry. The rise of the thematic system in response to the Arab Conquests coincides with Roman field armies being predominantly cavalry forces.

Militia systems typically get replaced because they degrade. Fief systems get replaced, at least within states, because the technology of warfare changes.

Militia systems tend to be more effective in defence than attack. Fief systems can be effective at both. The newly (re)conquered areas of the medieval Roman Empire were not organised under the standard thematic system. Moreover, the tagmata troops were the spearhead of the reconquests.

Not adopting fiefs

Surveying temperate zone Eurasia from the creation of the Parthian empire to the nineteenth century, the only significant farming states that did not use some variety of fief system to produce heavy cavalry were the Late Roman Empire, the medieval Roman state and China (when not ruled by a pastoralist dynasty).

The case of China has a straightforward geographical explanation: the lack of selenium in the soils of the Chinese heartland made it hard to raise horses. No Chinese dynasty was going to base its military-social system on a resource it did not control. Worse, one controlled by its major military threat: the steppe pastoralists.

The cases of the Late Roman Empire and the medieval Roman state are harder to explain. Three factors appear to be in play:

Roman law, with its absolute notion of property, is antipathetic to a pattern of landed service to warrior who provides military service (so layers of interest in property), which inhibits going down such a path.

The one group that is reliably hostile to economising on administrative costs are administrators. The Late Roman and medieval Roman states are the most bureaucratised states outside China. There is a persistent pattern of Roman officials seeking to channel as much authority and resources as possible through themselves.

Both the Late Roman and medieval Roman states lacked a mounted warrior class with direct access to authority.4

Factors (2) and (3) also apply in China. Particularly after the Song dynasty phases out the landed aristocracy.

The Late Roman Empire attempted to shift towards mounted armoured cavalry as its main striking arm while still using a centralised, highly bureaucratised, tax-and-payment system. Once the Battle of Adrianople (378) showed that the Romans had lost their operational advantage over their troublesome Germanic neighbours, operating a much more expensive administrative tail to put troops in the field was bound to tell against them over time.

In the C9th and C10th capitularies of the Frankish Empire, one can see a transition from a presumption that all freeborn males owed military service (a militia system) to groups of individuals supported a mounted warrior (a fief system). A shift based on an existing military elite holding manors in societies where the right to bear arms was a mark of free status and there were very limited administrative resources available to the state, so an urgent need to minimise administrative costs. A state that already used vassalage for that reason.

Conversely, the medieval Roman state restricted bearing arms to those in the service of the state and did not have a military aristocracy in the sense that the Latin West or samurai Japan had. Rather, there were prominent families with a history of military service to the state who lacked, until late in its history, independent military power. Exemptions from taxation due to service (e.g. the post) were a recurrent feature but limited to various forms of service to the state, which retained state monopoly for bearing arms.

The medieval Roman state thus practised a Weberian monopoly of military force. The Latin Kingdoms, and other warrior-franchise states, operated suzerainty systems. Military force was spread through the power structure. The right to bear arms was a mark of status, whether free or lordly.

The importance of the lack of a military aristocracy/warrior elite, and the restriction of the right to bear arms to those in the service of the state, is indicated by the fact that there was a long history, from the Late Roman and through medieval Roman history, of granting land conditional on military service to foreign warrior groups. Something that the Romans were not able to make work as a long-term pattern, as either the relationship broke down or, over time, the newcomers are assimilated into the Roman pattern of disarmed farmers.

Under the Roman Empire, Roman law had proved itself to be compatible with manorialism (in the Latin West). This was not, however, manorialism as a provider of local public goods or of service to the ruler.

Manorialism can exist without fief system and fief systems can exist without manorialism. In the Latin West, both existed and tended to operate in a mutually reinforcing way. In the medieval Roman state, neither existed until the development of the pronoia tax fiefs late in the history of the state.

A recurring feature of border policy in the medieval Roman state was to use depopulation as a border protection against raids. There was a recurring failure to keep frontier areas populated.

This contrasts with Latin Kingdoms granting rights of various levels of autonomy and status to folk on their borders, from marcher lords (including Palatine Bishoprics) to Anglo-Scottish borderers and Grenzer militia of the Habsburg military frontier. Often on the understanding that they would raid back. But to raid back requires the right to bear arms. This was rather less of an option in a state determined to maintain a monopoly of bear arms to those directly in its service.

A feature of centrally-funded forces is that they are vulnerable to cuts in funding. What became in the C11th the deliberate neglect of the thematic cavalry led to a lack of defence in depth, which had disastrous consequences after the destruction of most of the tagmata field army at Manzikert.

The drill and discipline of medieval Roman troops had a long-term pattern of being very patchy. Not something much seen during the Principate but one which begins to set in under the Dominate. Likely as part of the general decline in state capacity from the massive increase in the cost of creating and extracting surplus.

One of the advantages of fief systems is that magnates have an incentive to accumulate knights/mounted warriors. Even the medieval Romans wanted to accumulate knights, they were just foreign knights. (If you are going to centrally pay for mounted armoured lancers, mercenaries make sense as you do not need to pay for their full equipment and training costs.)

Conversely, with militia systems and a state monopoly of arms, the incentive is to acquire land without burdensome military obligations. Over the longer term, there is a pattern within the medieval Roman states of landed magnates having an interest in the central bureaucracy consuming resources, as that provided incomes for their families, yet not have it interfere with their local interests. This is an adverse set of incentives.

In the millennia-long strife between farmers and pastoralists, perhaps the most persistent divide in history, after that between farmers and foragers, the most highly bureaucratised states are, over the long term, conspicuous failures. The Latin West can deal with pastoralists by later C13th. The Poles, and especially the Hungarians, are able to develop their military systems to crush Mongol invasions even when the Mongols had superior numbers.

Muscovy can deal with pastoralists by C15th, conquering them in the C16th. Medieval Rome loses ground to them from 1071 onwards. China gets conquered by them in the C13th and C17th.

Nor did having a highly bureaucratised state mean that the medieval Roman state was able to avoid the (eventual) development of a fief system and lordly retinues, especially under the Palaiologoi. One that was an inferior system to the fief, castle and vassalage systems of the Latin Kingdoms and an expression of declining state capacity.

Mercantile interest and public goods

One of the long-term problems of the medieval Roman state is that the granting of commercial privileges to the medieval Italian city-states inhibited the ability of the Roman state to internally develop and access the revenue possibilities of trade, helping to generate its long-term pattern of downward resilience.

The granting of extensive commercial privileges to Italian city-states both reflected and entrenched the political weakness of the mercantile interest within the medieval Roman state. This meant that, over the longer term, the medieval Roman state also lacked a politically salient internal mercantile interest with a vested interest in the state providing effective public goods to balance off against landed magnates concerned to maintain their local authority, including resisting interference in their interactions with their local peasants.

The failure of the medieval Roman state to maintain investment in effective naval forces (so, maritime public goods) likely also reflects this lack of politically-salient mercantile interests. The only Latin Kingdom to grant similar commercial privileges to the Italian city-states was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which also lacked a politically salient indigenous mercantile interest.

Within Latin Christendom, the operation of medieval and early modern Parliaments (Cortes, Diets, Sejm, Estates, etc.) tends to show an underlying pattern of a politically salient mercantile interest fostering the capacities of the state. Where mercantile interests are significantly represented in Parliaments, Parliaments tend to meet more frequently and taxes tend to be higher.

Autocracies rarely raise land taxes, as they lack the feedback mechanisms to judge whether higher taxes will provoke revolts or not. Parliaments provide rulers with independent feedback on their officials, as well as feedback on the concerns of power-holders and groups represented in Parliaments and enable consent to be gained from the same for taxes.

A strong mercantile interest increases these benefits, due to the mercantile interest in effective provision of public goods. There can also be a feedback effect, as increasing income from land through specialisation can increase the interest of the landed magnates in effective provision of public goods. As distinct from resisting such to maintain authority over their peasants and not reduce their military bargaining power vis-a-vis the monarch, as are very clear patterns in Poland and Hungary.

We can compare English, Dutch, and (pre-American-silver) Spanish parliamentarianism, with the long-term failure of Hungarian and Polish parliamentarianism, to see the importance of mercantile interests in encouraging a more effective state. Especially compared to Parliaments dominated by landed magnates.

Without the power base of fortified cities and urban militias one sees in the Latin Kingdoms, or the competition between local dynasts one sees in medieval Japan, the disruptive effects of commerce tended to encourage suppression of mercantile interests, even as states relied on the trade revenue from the same:

A merchant is a specialist in exchange, buying and selling to obtain a profit. To increase profits merchants strive to enlarge the sphere of exchange, drawing subsistence or prestige goods produced within the kin-ordered or tributary mode into the channels of commodity exchange, the market. This transformation of use values into commodities, goods produced for exchange, is not neutral in its consequences. It can seriously weaken tributary power if it commercialises the goods and services on which that power rests. Granted too much latitude, it can render whole classes of tributary overlords dependant on trade, and reshuffle social priorities to favour merchants over political or military chieftains. Thus, societies predicated on the tributary mode not only gave impetus to commerce but also repeatedly curtailed it when it grew too strong. Depending on time and circumstance, they have taught merchants to “keep their proper place” by subjecting them to political supervision or to enforced partnerships wit overlords: by confiscating their assets, instituting special levies, or exacting high “protection” rents; by denigrating merchant status socially, supporting campaigns against commerce as sinful or evil, or even delegating mercantile activity to despised and powerless outsiders. The position of merchants is always defined politically as well as economically, and is always dependent on the power and interests of other social classes.

(Eric R. Wolf, Europe and the People Without History, Pp84-5)5

All social systems operate some form of implicit political bargaining, if only because of the varying capacity to enforce and resist various rules. With Parliamentary systems, there is much more explicit political bargaining, with such bargains being able to be put into law, so are stable enough to be worth the cost of such bargaining.

While medieval Japan did not have deliberative assemblies equivalent to medieval Parliaments, the system was pervaded by various forms of political bargaining, including ad hoc assemblies. Hence, after the Meiji Restoration, incorporating Parliamentarianism in the Japanese state was relatively easy (if not a complete success).

It is conspicuous that the medieval Roman state, like the Chinese state, never went down such a Parliamentary path, despite it being pervasive in the Latin Kingdoms. In both cases, the lack of a politically salient mercantile elite, the lack of a military aristocracy, and the strength of the bureaucracy, largely precluded doing such.

Conclusion

Late Roman military system that evolved in the C3rd collapses in the West in the C5th and in the East in the C7th. A new military system (thematic) evolves (into tagmata-thematic) that collapses in the C11th. A new military system (tagmata-mercenary) develops that collapses in the C13th. A new military system (pronoaia and retinues) develops that collapses in the C15th. With each collapse entailing a major loss of territory.

This is not a pattern you see among the major states of the Latin West. Yes, the medieval Roman state shows striking resilience, but it is a persistently downward resilience, not an upward resilience. The long-term pattern is bureaucratisation inhibiting the responsiveness and institutional vitality of the state.

Given that states dominate the creation and deployment of surplus, the most important question for the long-term path of a polity is: how is the state structured?

The argument is not that the adverse incentives made the medieval Roman state incapable: clearly it wasn’t as it lasted for so many centuries. The argument is that the adverse incentives tended to wear away at the capacity of the medieval Roman state over the longer-term; that they generated a tendency towards long-term institutional decline in contrast to the pattern we see in the major Latin kingdoms.

References

Christopher I. Beckwith, The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to China, Princeton University Press, 2023.

Lisa Blaydes, Eric Chaney, ’The Feudal Revolution and Europe’s Rise: Political Divergence of the Christian West and the Muslim World before 1500 CE,’ American Political Science Review, February 2013.

Marc Bloch, Feudal Society: Volume 2 - Social Classes and Political Organization, trans. L. A. Manyon, University of Chicago Press, [1940] 1961.

Elizabeth A. R. Brown, ‘The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe,’ The American Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Oct., 1974), 1063-1088.

Manuel Eisner, ‘Killing Kings: Patterns of Regicide in Europe, AD 600–1800,’ British Journal of Criminology, 2011.

J. H. Elliott, Imperial Spain 1469-1716, St Martin’s Press, [1963], 1964.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, 1977, 85:1, 59-77.

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

John Haldon, Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204, UCL Press, 1999.

John Haldon, Byzantium at War AD 600-1453, Osprey, 2002.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377],1967.

Henrik Jacobsen Kleven, Claus Thustrup Kreiner, Emmanuel Saez, ‘Why Can Modern Governments Tax So Much? An Agency Model Of Firms As Fiscal Intermediaries,’ Economica, Volume 83, Issue 330, April 2016, 219-246.

D.C. Lahti, B.S. Weinstein, ‘The better angels of our nature: group stability and the evolution of moral tension,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, 26 (2005), 47–63.

Nettie Liburt MS PhD PAS, “Trace Mineral Basics: Selenium”, Jul 29, 2018, for horses, at least 1mg per day but up to 2.5mg per day is necessary for optimum functioning, https://thehorse.com/19727/trace-mineral-basics-selenium/. By contract, humans need about 80-100mcg per day, or 0.1mg. See Margaret P. Rayman, “The Importance of Selenium to Human Health”, Lancet, 2000 Jul 15, 356(9225), 233-41.

Debin Ma, Jared Rubin, ‘The Paradox of Power: Principal-Agent Problems and Fiscal Capacity in Absolutist Regimes,’ Journal of Comparative Economics, Volume 47, Issue 2, June 2019, Pages 277-294.

Debin Ma, ‘Rock, scissors, paper: the problem of incentives and information in traditional Chinese state and the origin of Great Divergence,’ Economic History Working Papers, 37569, 2011, London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History.

Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, (trans. Jon Rothschild), Saqi Books, [1983] 2004.

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India, Pen & Sword Military, 2014.

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China, Pen and Sword History, 2016.

Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale University Press, 1997.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, Vol. 111, Issue 3, August 2017, 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, Luigi Pascali, “Cereals, Appropriability and Hierarchy”, Warwick Economics Research Papers, No.1130, October 2016.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

David Nicholle, Carolingian Cavalryman AD 768-987, Osprey, 2005.

David Nicholle, Graham Turner, Armies of the Caliphates 862-1098, Osprey Military, 1998.

M.M. Postan, The Medieval Economy and Society: An Economic History of Britain in the Middle Ages, Penguin, [1972] 1975.

Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted, Clarendon Press, 1994.

Ihor Sevcenko. ‘Constantinople Viewed from the Eastern Provinces in the Middle Byzantine Period,’ Harvard Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 3/4, Part 2. Eucharisterion: Essays presented to Omeljan Pritsak on his Sixtieth Birthday by his Colleagues and Students (1979-1980), 712-747.

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘Size and dynastic decline: The principal-agent problem in late imperial China, 1700–1850,’ Explorations in Economic History, Volume 54, 2014, 107-127.

Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else, Bantam Press, 2000.

Guo-Xin Sun, Andrew A. Meharg, Gang Li, Zheng Chen, Lei Yang, Song-Can Chen & Yong-Guan Zhu, “Distribution of soil selenium in China is potentially controlled by deposition and volatilization?”, Scientific Reports, 17 February 2016, 6:20953.

Jian’an Tan, Wenyu Zhu, Wuyi Wang, Ribang Li, Shaofan Hou, Dacheng Wang, Linsheng Yang, ‘Selenium in soil and endemic diseases in China’, The Science of the Total Environment, 284, (2002) 227-235.

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure,’ Physics of Life Reviews, 36 (2021) 100–136.

Peter Turchin, War and Peace and War: The Life Cycles of Imperial Nations, Pi Press, 2006.

Peter Turchin, Thomas E. Currie, Edward A. L. Turner, and Sergey Gavrilets, “War, space, and the evolution of Old World complex societies”, PNAS, vol. 110, no. 41, October 8, 2013, 16384–16389.

Edward J Watts, The Final Pagan Generation, University of California Press, 2015.

Andrew Wilson, ‘Developments in Mediterranean shipping and maritime trade from the Hellenistic period to AD 1000,’ in Maritime Archaeology and Ancient Trade in the Mediterranean, (edited by Damian Robinson and Andrew Wilson), Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology Monographs, 2011, 33-60.

Eric R. Wolf, Europe and the People Without History, University of California Press, [1982] 1997.

Jan Luiten van Zanden, Eltjo Buringh, and Maarten Bosker, ‘The rise and decline of European parliaments, 1188–1789,’ The Economic History Review, 65, 3 (2012), 835–861.

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw, & Marcus W. Feldman, “Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck”, Nature Communications, (2018) 9:2077

“the particular way [species] interact with and find a way to make a living in their environment.” (Heying and Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century, p.5.) The Homo sapien ability to shift between niches, and create new niches, creates much more flexible dynamics than is normal with species.

Controls a territory of at least one million square kilometres.

Emperor Kinmei (r. 539-571), 29th Emperor, is regarded by various historians as the first historically verifiable Japanese emperor. The current Emperor (Naruhito) is the 126th Emperor.

The Greek East also never developed manorialism.

I don’t agree with his analytical framework, but the underlying point is correct.

Love this paper, and the fascinating impact of the Roman law of absolute ownership (cf common law ownership)