Escaping the kin-group trap

Daniel Pipes’s revealing errors about the slave warriors of Islam. (Revised version of paper presented to Melbourne University Medieval Roundtable in May 2025.)

Islam produced slave warriors (ghulam, mamluks, janissaries) on a scale no other civilization did. This pattern of militaries based on slave warriors lasted from early to mid-800s to the early to mid-1800s.

The extreme version of this were Mamluk states, where former slaves were the ruling elite—they went “from slaves to lords”. Mamluk Egypt (1250-1517) and the Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526) were the most powerful of such states, but not the only examples. After a brief hiatus at the time of the Ottoman conquest, the mamluks remained the ruling elite of Ottoman Egypt until Muhammad Ali’s (1769-1849) suppression of them, most notoriously in the Massacre of the Citadel in 1811.

In his monograph of his PhD dissertation, Daniel Pipes—Slave Soldiers: The Genesis Of A Military System, Yale University Press, 1981—identifies a pattern:

A new dynasty rarely depends on slave soldiers at the time when it comes to power;15 they usually turn up two or three generations later, as a ruler casts about to replace unreliable soldiers with ones from new sources that he can better control. Typically, military slaves serve the ruler first as royal bodyguards, then move to other parts of his entourage, and from there to the army, government, and even into the provincial administration. As the ruler increasingly relies on military slaves, they acquire independent power bases and sometimes take matters into their own hands, either controlling the ruler or even usurping his position.16 Not always, however: in many cases, when judiciously used, military slaves render competent and faithful service to their masters for long periods of time. (p.xix.)

15. Exceptions usually come from dynasties founded by military slaves, since they rely heavily on their own corps.

16. The special and fascinating phenomenon of soldiers of slave origins becoming rulers will not be considered in this study. This means that much of the evidence from the Mamluk Kingdom will not be analyzed.

Daniel Pipes describes the pattern of such slaves:

The career of a military slave follows a tight pattern. Born a non-Muslim in some region not under Muslim control,17 he is acquired by the Muslims as a youth old enough to undergo training but still young enough to be molded by it. Brought to Islamdom as a slave, he converts to Islam and enters a military training program, emerging some five to eight years later as an adult soldier. If he has special abilities, he can rise to any heights in the army or (sometimes) in the government; while most military slaves spend their adults lives in the ruler’s army, they are not just soldiers but a key element of the ruling elite in most Muslim dynasties. (Emphasis added.) (p.xix.)

17. Exceptions exist, notably in the Ottoman and Filali dynasties.

The bolded claim is, as we shall see, over-stated.

In this post, I am not going to wrestle with all the nuances. Instead, I will be using what economists call stylised facts: simplifications that are simple enough to be tractable but hopefully not so simple as to lead analysis astray and that seek to identify “robust (descriptions) of general tendency”.

I will also generally apply the Australian principle of social analysis—in the race of life, back self-interest, it’s the only horse that’s trying—while touching on how religion can generate counter-examples to that principle.

The aim is to identify general mechanisms while examining how the contingency of human action leads to widely varied outcomes. While the mechanisms are general, their manifestations are particular.

Understanding religious dynamics

Humans developing language meant the development of symbolic behaviour and self-consciousness-–the ability to assemble, package and assess information. The interaction of our ultra-sociality and self-consciousness led to development of religion, especially as our social interactions scaled up.

The realm of the divine is the realm of authority from which there is no reliable feed-back—hence the importance of revelation—but we can seek to placate or take solace from, hence sacrifices, hymns, prayers, rituals. This creates a realm of authority that is not open to be directly interrogated: at least, not by the uninitiated or by ordinary mechanisms of understanding.

The realm of the sacred is the realm where trade-offs from outside the realm of the sacred will be resisted or simply denied. This provides an ordering function by constraining behaviour and channelling expectations.

None of the foregoing presumes the existence of the supernatural. Secular systems can have a realm of the divine—e.g. the imagined future of Communism—and a realm of the sacred—e.g. the US Constitution. It is completely reasonable to talk of political or secular religions.

The role of the sacred as being the realm within which trade-offs are rejected—or at least strongly resisted—can lead to people acting as devoted actors rather than (instrumentally) rational ones. For revealing analysis of such dynamics see:

Scott Atran, ‘“Devoted Actor” versus “Rational Actor” Models for Understanding World Conflict,’ Briefing to the National Security Council, White House, Washington, DC, September 14, 2006. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6801978.pdf

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6123217_Sacred_Barriers_to_Conflict_Resolution

Farmers versus pastoralists

Farmers-versus-pastoralists have been one of the great divides of history, rivalled only by farmers-versus-foragers. The Rwandan genocide (1994), the Hutu massacres (1996-7) and Darfur genocide (2003-5) are recent manifestations of killings between farmers and pastoralists—a strife that has claimed tens of millions of lives across history.

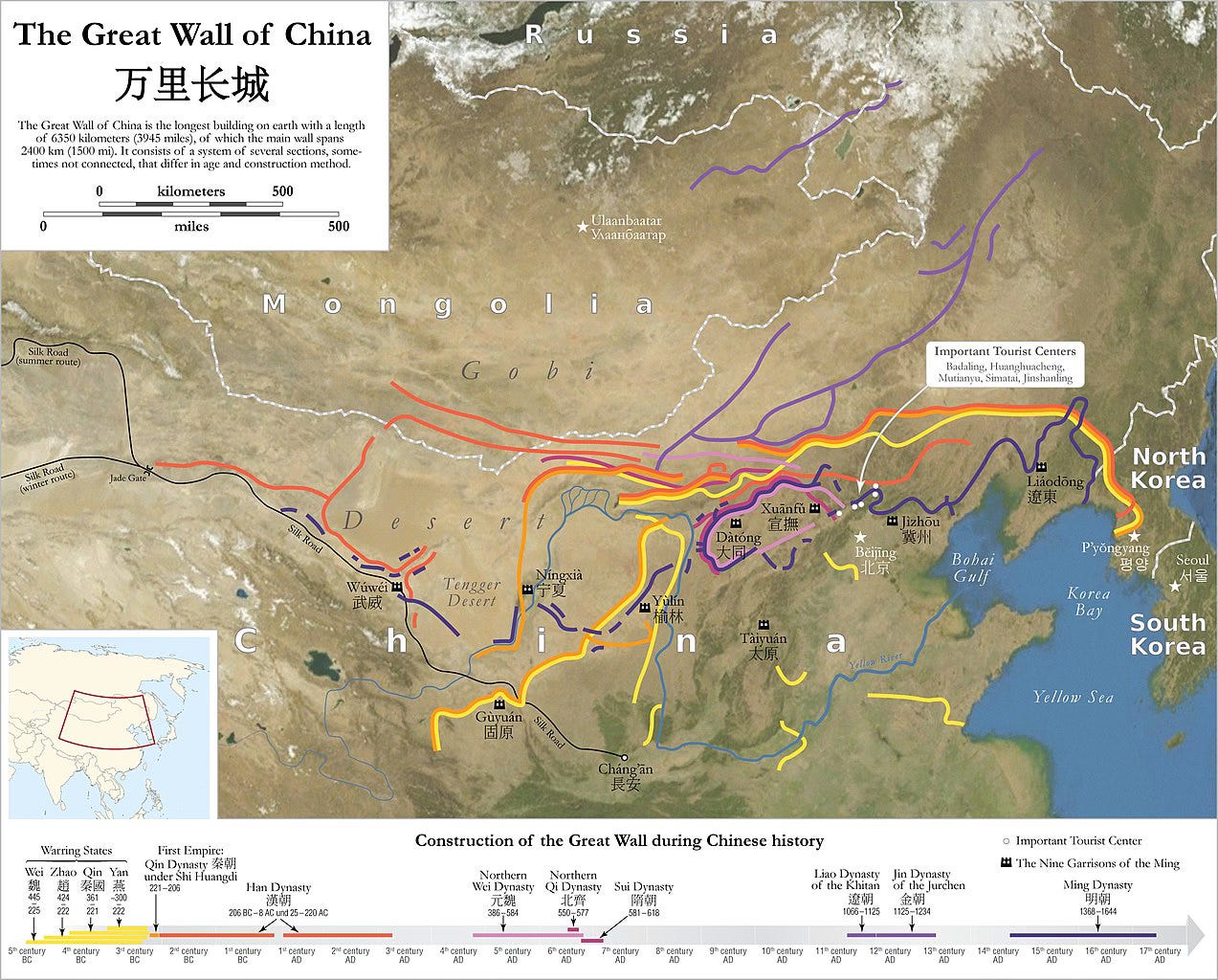

One manifestation of the contestations between farmers and pastoralists across the generations has been how farming polities have constructed border walls to inhibit pastoralists raiding (and to control trade). These vary from the most famous—the Ming Great Wall of China—to the most mysterious—a wall about 100 miles in length across Syria built around 4,000 years ago. Again and again, they were built to divide farmers from pastoralists.

The farmers typically regarded pastoralists as thieving, raiding, murdering, raping, enslaving bastards. The pastoralists typically regarded farmers as weaklings could not defend their own. In accordance with stereotype accuracy, they were both correct.

The pattern of peasant farmers eating plant-dominated—so protein-limited—diets, working in water-logged fields full of parasites and pathogens, being periodically conquered by pastoralist elites is a pattern we see across the Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Indus, Ganges and Yellow River valleys. In two cases—the Mongol (Yuan) and Manchu (Qing) conquests—it extended to the Yangtze River valley.

The most extreme version of this pattern of pastoralist conquest is Egypt. From when the last native-born pharaoh (Nectanebo II) fled the Persian conquest in 342BC to the Officer’s Revolution of 1952, Egypt was ruled by foreign elites. There was a state in Egypt, but there was no Egyptian state. From the Arab conquest of Egypt in 641-2 to Muhammad Ali’s Massacre of the Citadel in 1811, those elites were pastoralist elites.

Pastoralist conquerors of farming lands regularly conquered peoples who hugely outnumbered them and who then tended to deeply influence the culture of the pastoralist-in-origin ruling elite. The Sinification of such elites in China, and the Iranisation of such elites in the Middle East, are cases in point.

The Taj Mahal, for instance, is a Persian building that happens to be in India. From the Atlantic coast to northern India, Islamic culture became a mixture of Arabic theology, Persian high culture and Turco-Mongol militarism.

Pastoralists and kin-groups

Pastoralism generates mobile assets (animal herds) that need to be protected. Animal herds that are passed down male lines, as you cannot mind herds with children in tow.

Pastoralist societies are thus based on patrilineal kin groups, where men inherit the herds and warrior-teams made up of close kin—who have grown up together—protect the herds, women and children. Steppe pastoralism—where the men might be away—generate armed, so higher status, women. Oasis pastoralism, less so. Lineage could also be a useful way of organising access to pasture and water resources

Pastoralists are highly mobile, have animal-rich—so high protein, nutrient-rich—diets and are trained in weaponry from an early age. This makes raiding a recurring feature of such societies, especially when polygyny transfers women up the social scale, leading to lower status men with no marriage prospects within the community.

As economist Pauline Grosjean notes:

Cultures of honor prevail in pastoralist societies. A herder’s livelihood is precarious in a way that a farmer’s is not: he can easily lose most of his wealth through theft. Aggression and a willingness to kill can be essential to build a reputation for toughness and deter animal theft.

See: ‘A History Of Violence: The Culture Of Honor And Homicide In The US South,’ Journal of the European Economic Association, (2014), 12: 1285-1316. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1917113

She finds that a culture of honour persists among Scots-Irish, but only in areas with a history of weak institutions.

The Middle East as an incubator of monotheism

The Middle East is where the ecological boundaries between farming and pastoralism are most interwoven. There is a long history of movement by individuals, families and groups across the farmer/pastoralist divide.

This means there is a strong social selection advantage in the region for belief systems that generate a moral unity that can unite within, and across, the farmer/pastoralist divide. Monotheism generates such a unified moral order. Monotheism replaces the order v. chaos moral metaphysic common to pastoralist and (especially) farming societies—see the Egyptian concept of maat, the Chinese concept of dao or the Mongol concept of tore—with a good v. evil moral metaphysic.

The Middle East has generated, among others, two particularist monotheisms (Judaism and Zoroastrianism) and two universalist monotheisms (Christianity and Islam). The two universalist monotheisms have salvationist theologies that have proved particularly effective at generating devoted actors.

Christianity grew up inside the urbanized, law-bound Roman Empire. Christianity—the Gospel of Love—is more like Buddhism—the Doctrine of Compassion—in various ways than Christianity is like the other monotheisms. Neither Christianity nor Buddhism are Law-giving religions. Both have strong monastic traditions. Both have to work at having warrior traditions—notably Chivalry and Bushido.

Islam arose in the strongest concentration within the Middle East of pastoralist societies (the Arabian peninsula).

Christianity represents the sanctification of a farming synthesis and Islam the sanctification of a pastoralist synthesis. In Eastern Europe, for example, all the farming polities became Christian, all the pastoralist polities became Muslim. The most recent polity established by raiding pastoralists is Saudi Arabia (in the 1920s).

Christianity—especially Latin/Western Christianity—represents the sanctification of the Roman (farming) social synthesis:

Law is human, so law-making operates outside, and does not require, religious authority.

Single-spouse marriage.

Mutual consent for marriage.

Bans on cousin/consanguineous marriage.

Testamentary rights to all free individuals.

Christianity led to the suppression of kin groups across manorial Europe. The exceptions were the pastoralist regions of the Celtic fringe and Balkan highlands, where the position of local power holders rested on kin-groups.

In the competitive jurisdictions of medieval-and-later Europe, this suppression of kin-groups put the Homo sapien advantage of non-kin cooperation “on steroids”, generating social selection that resulted in such an organizationally capable set of states, culture and institutions that European, and Neo-European, states came to dominate the planet.

Islam’s sanctification of pastoralist synthesis

Islam—especially in its original form—represented the sanctification of the (Arabian) oasis pastoralist social synthesis:

Law is based on revelation and controlled by the ulama (religious scholars), apart from qanun: rules for the internal operation of states issued by ruler (i.e., where Sharia is silent).

Polygyny—up to four wives, apart from “those thy right hand has seized” (ma malakat aymanuhum or milk al-yamin).

Cousin marriage is notionally discouraged, yet is permitted: especially given that Ali, Muhammad’s first convert and first cousin, married his daughter Fatima.

No pressure against kin-groups.

Sanctification of raiding of non-Muslims who had not submitted to Muslim rule, including slavery and woman-stealing.

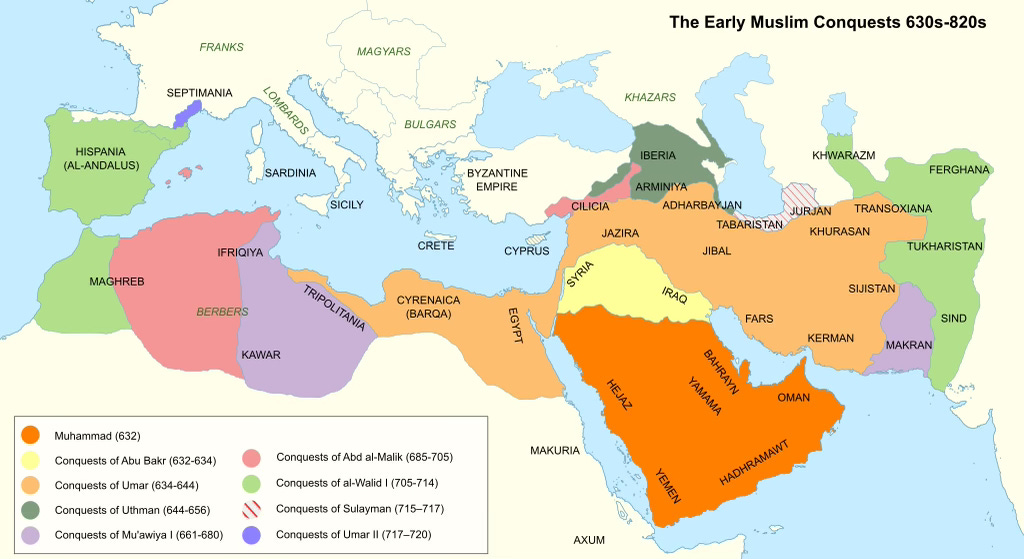

This generated a highly aggressive system, that began with the greatest wave of religious conquest in history, and came to aggress against every culture it came up against.

Pastoralists and kin-groups (II)

Kin-groups, particularly patrilineal, pastoralist kin-groups, typically generate loyal and effective warriors. The standard pastoralist response to the polygyny-generated shortage of wives is “those people over there have women, steal theirs”. A professor of fiqh at Al Azhar university sets out the justification of this within Islam.

Thus, this is a response that Sharia—the rules of the Sovereign of the Universe, discovered by fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), and which apply to all humanity—sanctifies. Hence Islam’s tradition of jihad and ghazis—holy warriors on the borders of Islam raiding (and so “softening up”) non-Muslim borderlands—and Islam’s concept of the martyr as a warrior who dies while fighting for the umma, the Muslim community.

After the Abbasid Revolution “de-tribalised” the Caliphal military system—as discussed below—the conquest expansion of Islam stopped. Expansion by conquest only resumed on any scale under the (pastoralist) Turks. Though Amazigh (Berber) and Mongol pastoralists did generate Muslim conquerors, they did not significantly expand the borders of Islam.

Expansion of Islam into the Malay world and Indian Ocean Islands—areas lacking major grasslands and so local pastoralists—was mainly by trade. Sharia’s incorporation of significant elements of Roman commercial law gave it a comparative advantage over other legal traditions to the East and South of Islam.

Christianity has a long history of being antipathetic to kin-groups. Even today, much of the appeal of Pentecostalism in Africa is that its congregations provide both refuge from the demands of kin-groups and an alternative support network.

As a result of both the Classical (Graeco-Roman) and manorial medieval Christian suppression of kin-groups, European/Western thought has a long history—that goes back at least to Hobbes (1588-1679) and Locke (1632-1704) —of not taking the significance of kin-groups seriously. If your culture has had no significant kin-groups for one or two millennia, or more, they are not likely to figure in your analytical frameworks.

Pastoralists can make excellent warriors, provided they can be organized in ways that are either convergent with their kin-group loyalties or which successfully systematically override them (as Genghis Khan’s military reforms famously did). A major difficulty is that kin-groups can also colonize institutions and organisations—rulers come and go, the kin-group is forever. Much of the medieval Papacy’s antipathy to kin-groups was clearly to block them colonizing the church, with the clan-ridden Irish Church that the medieval Papacy had great problems exerting control over being a salutary “horrible example”.

Law and revelation

Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's.

This famous passage is about realms of authority. The accounts in Matthew 22:15–22 and Mark 12:13–17 say that the questioners were Pharisees and Herodians, while Luke 20:20–26 says only that they were "spies" sent by "teachers of the law and the chief priests".

The various versions of this much-cited Gospel passage did not presage the separation of Church and State—if anyone claims such, medievalists just point and laugh. What it presages is the separation of law and revelation. Caesar can legitimately legislate without reference to revelation. So can Alfred the Great.

This is not the view in Judaism, Islam or post-Vedic (“Hindu”) Brahmin civilisation. It is the view in other civilisations.

Islamic rulers could only legislate (qanun) in the silences of Sharia. Rulers could issue what were essentially “public service regulations”; rules about the internal operation of state administration. This meant that the mechanisms (discussed below) that the Church and the rulers of Christendom—and previously, the Greek city-states and Roman Republic—used to suppress kin-groups were not available to Islamic rulers.

It also meant that political bargains could not be directly entrenched in law. This largely “locked in” autocratic government: government that might be leavened by shura consultation but could not be Parliamentary in any serious sense. (The one non-autocratic exception, the Republic of Sale, was a corsair city-state founded by Moriscos that clearly followed Christian models of self-governing cities.)

This severe limitation in the ability to entrench political bargains in law was very different from, for example, samurai Japan. While Japan never developed formal Parliaments, it did use ad hoc assemblies. Political bargaining was pervasive in the system: bargains that could be, and were, entrenched in law, making them worth the effort. When the post-Vedic (“Hindu”) brahmins took over law, Indian civilisation also became a series of autocracies, blocking any revival of the previous pattern of ganasangha republics.

Lineage versus locality

Locality is an alternative organising principle to lineage. The suppression of kin-groups again and again has involved elevating locality over lineage. We see this in Solonian Athens, in the Roman Republic, in manorial and congregational Christian Europe.

Genghis Khan did a version of this when he insisted that each 10 person warrior squad (arban), that was his base military unit, live together with their families. The arban was a unit of 10 households that provided 10 warriors, embedded in an ascending decimal system—10 arbans made up a jaghan; 10 jaghans (so 100 arbans) a mingghan; 10 mingghans a tumen (10,000 warriors).

This system was clearly designed to override the negative dynamics of kin-groups while creating a system both legible to, and controlled by, the ruler. Over time, it created (or, perhaps, re-organised) a hereditary aristocracy plus new identities, as the value in pastoralist societies of warriors who grew up together asserted itself.

Elevating locality over lineage is not enough in itself. The Christian suppression of kin-groups—via the manorial system and more broadly via its congregations—involved:

legislating restrictions on marriage, enforcing a single-spouse marriage system based on very extensive incest bars, that spread out marriage connections;

requiring mutual consent for marriage, so women’s wombs were not assets of, nor allocated by, the kin-group;

insisting on individual testamentary rights, so that asset transfer across generations was controlled by individuals, not the kin-group; and

suppressing or replacing any form of ancestor reverence, abolishing ritual boundaries between kin-groups. (Balkan clans got around this bar on ritual differentiation by adopting a patron saint specific to the clan.)

None of these mechanisms, except the last, were available to Islamic rulers, as marriage and inheritance law were part of Sharia, so controlled by the religious scholars (ulama), based on revelation and the words and actions of Muhammad and the early Caliphs. The ritual “flattening” of monotheism abolished ritual boundaries, based on ancestor reverence, between kin-groups, making parallel cousin marriage—within the kin-group—much more common, so it reinforced clan ties.

Patterns within Islam

Sociologically, Islam can be divided into five patterns. One is minority Islam—Ibadis, Alevis, Alawites, Ismailis, Ahmadis, and so on (though not all these groups are recognised as Muslim by other Muslims).

Among majority areas of Islam, there are four patterns based on having strong kin groups or not and significant cousin marriage or not:

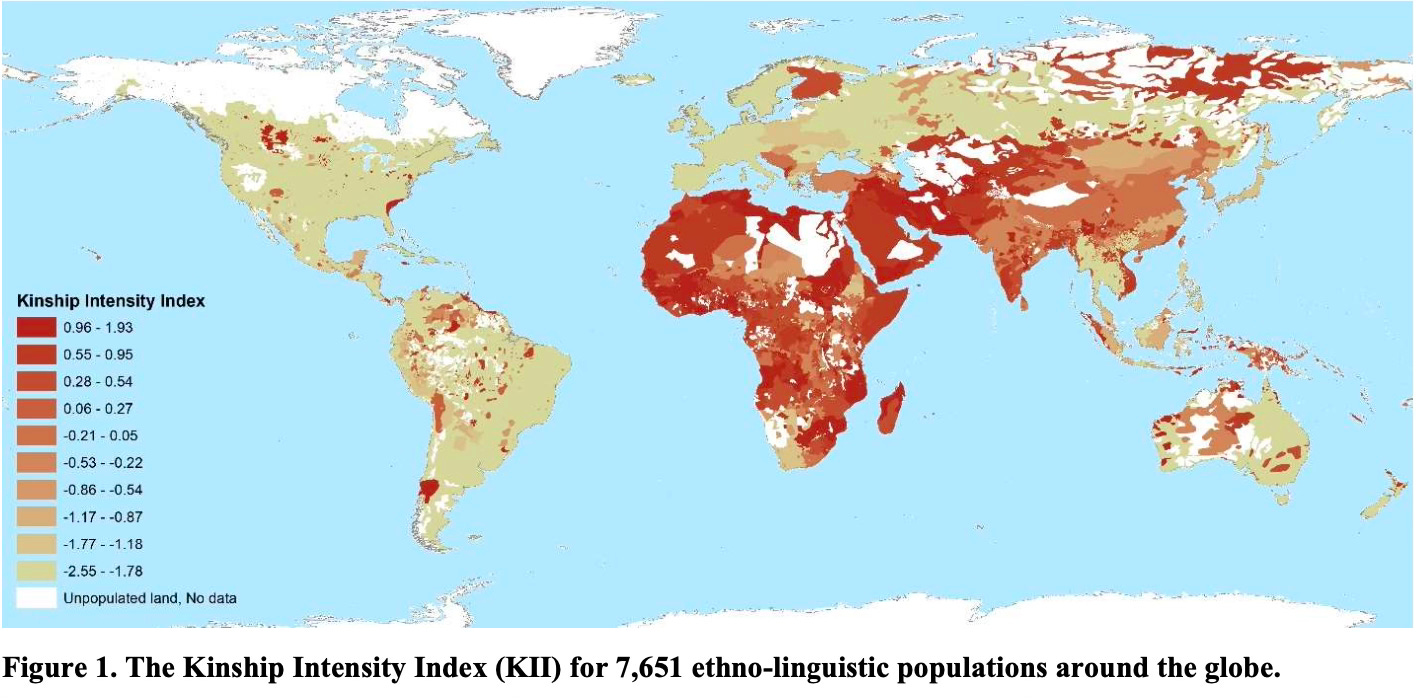

Middle East/North Africa/Pakistan/Turkey/Afghanistan (MENAPTA) has both strong kin groups and significant cousin marriage. I refer to this region as The Greater Middle East. It is the region of original Arab Conquest Islam up to the end of the Umayyad caliphate in 750.

The rest of South Asia has weak or absent kin groups, but significant cousin marriage.

Central Eurasian or Steppe Islam has strong kin groups, but little cousin marriage.

Malay and Islander Islam has weak or absent kin groups, with little cousin marriage.

Statistical analysis has found a negative correlation between having an Islamic majority population and being democratic. If, however, Islam is dis-ambiguated, that negative correlation goes away and becomes specific to Islam within the Greater Middle East, and even more specifically, the Arab world.

Slave warriors in Islam

As a major military system, slave warriors are distinctive to Islam. While there are examples of slave warriors outside Islam, these are transitory or peripheral.

Slave warriors as a military system are not, however, a general pattern within Islam. They only occur within—or from—the area of Islam nowadays characterised by having strong kin groups, with cousin marriage (MENAPTA/the Greater Middle East).

Slave warriors as a military system only emerge in the Greater Middle East some decades after the Abbasid Revolution of 747-750 which established the principle of the equality of Muslims. Before that, converts to Islam had to register as clients (malwa) of Arab tribes, creating a two-tier system. The state ruled over by the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates was very much an Arab Empire.

We can distinguish three broad military systems within Islam.

Lineage and households: Use of local pastoralists as the mainstay of military forces, operating, or at least recruited, through local lineages, even if a standard way of aggregating together pastoralist households was then imposed. This is the pattern we see with the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661), the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750), various Sahel and Amazigh (Berber) states, and in Central Eurasian (i.e. steppe) states, including the Crimean Khanate.

Conventional: Cavalry either with tax-fiefs (iqta, tuvul, timur, zamindar) or directly paid plus directly paid infantry. This is the pattern we see in Malay and Islander Islam and in South Asian Islam—if the original conquerors come out of Central Eurasia.

Extensive use of slave soldiers—ghulam under the Abbasids, later mamluks, then janissaries under the Ottomans—who either held tax-fiefs or were directly paid. This pattern is restricted to within the area of the original Arab conquests, or areas conquered out of that region—notably, the Delhi Sultanate and Ottoman Empire—and starts a few decades after the Abbasid Revolution (747-750).

There is an apparent paradox here. Yes, Islam produced systems of military slaves that in their scale and duration far surpass anything that appears in other civilisations.

Yet, these systems operate in, or from, a very specific region of Islam. The first glimmerings appear around 820 in the heartland of the Caliphate. This is two centuries after Islam first became a religion of rulership. They persist for around a thousand years.

Nevertheless, there are entire regions and forms of Islam that either never used slave warriors or for whom they were a minor or peripheral feature.

After the Abbasid Revolution

Even in the Greater Middle East/original Conquest Islam, military slaves only appear some decades after the Abbasid Revolution. The Rashidun (632-661) and Umayyad (661-750) Caliphates used Arab pastoralist armies organized via their lineages (“tribes”). A pattern that Steppe Islam would continue to use—unless they adopted some version of decimal aggregation of households—until conquered by the Rurikid Muscovite or Romanov Russian imperial state or the Qing Empire.

The requirement for Muslim converts (malwa) to register as patrons of a specific Arab tribe created a very two-tier system. The Abbasid Revolution—based on support from the previously Iranian-ruled regions—was prosecuted in the name of the equality of Muslims and so overthrew this system.

This created the paradox of kin-groups continuing to operate but no longer being available as the basis for organizing military forces. As Daniel Pipes tells us:

Shortly after Abu Muslim arrived in Khurasan in 129/747, he founded the first nontribal corps of Muslim soldiers. He did this by instituting a new Military Register to parallel the old one. Rather than listing soldiers by their tribal affiliation (nasab), the new register listed “the names of the soldiers, their fathers’ names, and their villages.” By thus eliminating any reference to tribal genealogy, Abu Muslim made it possible for non-tribesmen to join the army as full-fledged soldiers without needing an Arabian patron. The transition from tribal to geographic Military Register may have taken place gradually. The Abbasids did not list everyone in the new register but for some years maintained two registers, one tribal and another geographic; the first listed tribal Arabians and the second, all nontribal persons. When the Abbasids came to power they stopped adding names to the tribal register, allowing it to dwindle in size through natural attrition. (Pp174-5)

This is another instance of locality replacing lineage. The principle of the equality of Muslims meant that military forces could no longer be organized through Arab tribes. Kin-groups still existed, which meant they would (and did) colonise locally-raised forces, degrading their quality and reliability.

Non-pastoralist kin-groups were generally not, however, a useful source of warriors by lineage, while it is much harder to operate a coherent military force via culturally diverse lineages.

The strong restrictions on the law-making powers of rulers meant that kin-groups could not be suppressed. So, rulers needed soldiers who had no connections to local kin groups and whose only recognized local connection—including by them—was to the lord or ruler.

Who satisfied that criteria? Foreign (i.e., imported) slaves did.

Slavery

The key element of slavery is not that humans become property; it is that such a level of domination is imposed so as to turn them into property. A slave is property, so is not a legal person. They have no legal property or family rights, and no connection to anyone else that commands legal respect, except that to their master, their owner.

Hence slavery as social death: indeed, slavery has often been imposed as the alternative to being killed. The only legally recognized connection being to their master is very much reinforced if they are geographically separated from their kin—are imported from outside the polity—or are religiously separated—are recruited from non-Muslim residents of the polity.

The use of slave warriors in Islam—ghulam, mamluks, later janissaries—was a way of not having one’s military forces colonised by local kin-groups. Such slave warrior systems used a mixture of no other local connection other than to one’s master; close supervision; and the prospect of earning freedom and status—from slave to lord, as the mamluks said—to create an effective military system.

The mamluk elite of Egypt was also perhaps the least nepotistic elite in history, as the children of mamluks were (at least notionally) banned from holding fiefs. A ban whose enforcement varied but tended to increase over time, as every Mamluk emir needed to be able to offer potential lordship to their own military slaves.

Perhaps the clearest indication of the utility of the system as a slave system in the context of the Greater Middle East is provided by the decline of the Janissaries. They were a loyal and effective fighting force until Sultan Selim II (r.1566-1574) allowed them to marry (1566). The devşirme boy-tax recruitment declined as the Janissary corps expanded and other recruitment methods were used.

Over time, they became able to put their sons into the Janissary corps, own land and run businesses. The result was a decline in both the loyalty and the military effectiveness of the Janissaries. They became an exploitative military caste that deposed and elevated Sultans.

Eventually, Sultan Mahmud II (r.1808-1839) raised a modern drilled army and artillery corps in rural regions, provoked the Janissary corps into revolt, and used his new army to massacre them wholesale in what is known in Turkish history as The Auspicious Incident (June 1826).

The Pipes thesis

Daniel Pipes argued that moral disappointment due to the failure to live up to Islamic ideals led to local withdrawal from political engagement, so the recruitment of hardy, “marginal area” warriors.

This explanation for the origins of military slavery confirms the argument for its Islamicate rationale ... Briefly, that rationale maintains

that the impossibility of attaining Islamic public ideals caused Muslim subjects to relinquish their military role;

that marginal area soldiers filled this power vacuum;

that they became rapidly unreliable, creating the need for fresh marginal area soldiers and a way to bind them;

that military slavery supplied a way both to acquire and to control new marginal area soldiers.”

In the first development of military slavery, the following sequence occurred.

Muslim subjects in the Fertile Crescent and Iran had withdrawn from public affairs by the end of the 2d/8th century, a consequence of their disappointment with Abbasid rule (and possibly because Muslims had become a large portion of the population).

Some or many of the Abbasid military supporters from Khurasan were marginal area soldiers.

The descendants of these soldiers had grown unreliable by the 190/ 810s, as is shown by the poor show they made in fighting for al-Amin against al-Ma’mun. Al-Ma’mun needed new sources of marginal area soldiers and a way to control them.

Military slavery fulfilled both these needs.

Once the institution of military slavery had been established, it acquired a momentum of its own and became available to rulers and dynasties with diverse needs. Mainly it spread because Muslim rulers, under the restriction of unattainable Islamic ideals, needed some way to acquire and control outsider soldiers from marginal areas. Military slavery developed early and remained a basic institution of premodern Islamicate public life. It did not arise as a result of accidental features of Abbasid history; much less was it the result of al-Ma’mun’s personal decision. Rather, it came into existence and took hold in response to fundamental facts of Islamicate life. Military slavery was an institution implicit in the Islamicate order; the Abbasids (and probably the Spanish Umayyads as well), with the Marwanid model before them, resorted to it naturally. (Pp193-4)

This thesis is revealingly wrong. The error comes from two continuing errors that we see in some scholarship (though less so over time) and much more commentary:

Conflating the patterns of the Greater Middle East—North Africa, Middle East, Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan—with the wider patterns of Islam as a civilization.

Ignoring the significance of kin-groups, that are pervasive across human societies—apart from Christian-based societies, riverine SE Asia and various islands and archipelagoes: areas that either lacked pastoralists or in which pastoralists were peripheral.

Slave warriors were not, however, a pattern copied on any scale by other civilisations—not even Islam East of the Delhi Sultanate or by Steppe Islam. This points to the importance of factors specific to Greater Middle Eastern Islam. More specifically, deeply entrenched kin groups, that were not available as mechanisms to organize warriors, interacting with a general feature of Islam—rulers with very limited law-making capacities—making slave warriors both a desirable and a viable military system.

Wider resonances

One wonders how much kin-groups affect the effectiveness of contemporary Middle Eastern—particularly Arab—military forces. Political scientist Kenneth Pollack has identified a range of cultural factors that explain the pattern of strengths—and striking weaknesses—that Arab conventional military forces display. He notes the complicated role of clans in Arab society and militaries, suggesting that the neighbourhood is beginning to replace clan as a key identity—locality over-riding lineage. Conversely, legal scholar Mark Weiner notes that Yasser Arafat very much relied on revising clan politics when he returned to Palestine after the 1993 Oslo Accords.

A similar question arises with Chinese military forces. How much did their pattern of declining effectiveness across the life of a dynasty represent the corrosive effects of kin-group colonisation getting worse over time? The continuing issue of corruption in the PLA suggests that the significance of networks and connections within Chinese culture and society continues to have institutionally corrosive effects.

Malay, Islander, Steppe and Arab Conquest Islam all managed to have effective military forces without relying on, or even using, slave warriors. Clearly, it was not general features of Islam that determined the creation of the distinctive-to-Islam systematic use of slave warriors. It was the interaction of features of Islam with the social dynamics of the Greater Middle East—after the Abbasid Revolution—that was crucial.

ADDENDUM: This lecture includes Safavid Iran using slave soldiers to get around the problem of relying on kin-groups for warriors (41:37).

References

Mikael S. Adolphson, The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan, University of Hawaii Press, 2000.

Scott Atran, ‘“Devoted Actor” versus “Rational Actor” Models for Understanding World Conflict,’ Briefing to the National Security Council, White House, Washington, DC, September 14, 2006. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6801978.pdf

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6123217_Sacred_Barriers_to_Conflict_Resolution

Shadab Bano, ‘Military Slaves In Mughal India,’ Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol.67 (2006-2007), 350-357. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147956

Paul D. Buell, Judith Kolbas, ‘The Ethos of State and Society in the Early Mongol Empire: Chinggis Khan to Güyük,’ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 2016;26(1-2):43-64. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301740605_The_Ethos_of_State_and_Society_in_the_Early_Mongol_Empire_Chinggis_Khan_to_Guyuk

Eric Chaney, ‘Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present,’ Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2012, 363-414. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2012a_Chaney.pdf

Chris D. Frith, ‘The role of metacognition in human social interactions,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2012, 367, 2213–2223. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3385688/

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Pauline Grosjean, ‘A History Of Violence: The Culture Of Honor And Homicide In The US South,’ Journal of the European Economic Association, (2014), 12: 1285-1316. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1917113

Ulrich Haarmann, ‘The Sons of Mamluks as Fief-holders in Late Medieval Egypt,’ in Tarif Khalidi (Ed.), Land tenure and social transformation in the Middle East, American Univ. of Beirut, 1984, 141-168. https://storage.freidok.ub.uni-freiburg.de/publications/4623/sS7By3XW6nkKJJPT/Haarmann_The_sons_of_Mamluks.pdf

Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, [1988] 2014.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

Lhamsuren Munkh-Erdene, ‘Political Order in Pre-Modern Eurasia: Imperial Incorporation and the Hereditary Divisional System,’ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 2016;26(4):633-655. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305693051_Political_Order_in_Pre-Modern_Eurasia_Imperial_Incorporation_and_the_Hereditary_Divisional_System

K.W. Nicholls, Gaelic and Gaelicized Ireland in the Middle Ages, Lilliput Press, [1971] 2012.

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Harvard University Press, [1982] 2018.

Daniel Pipes, Slave Soldiers: The Genesis Of A Military System, Yale University Press, 1981.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Philip Carl Salzman, Pastoralists: Equality, Hierarchy, And The State, Westview Press, 2004.

Philip Carl Salzman, Culture and Conflict in the Middle East, Humanity Books, 2008.

Yuhua Wang, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Mark S. Weiner, The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom, Picador, 2014.

Fei Xiaotong, From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society, trans, with an introduction and epilogue, by Gary G. Hamilton and Wang Zheng, University of California Press, 1992.

I love all your medieval history work, but I really do think this is my absolute favourite of your papers. I find your analysis of kin-groups compelling, as someone who does comparative legal history, including in Asia.

Very interesting article. The topic of warrior slaves is fascinating.