History fails

How not to understand (nor learn from) the past.

There are three ways in which people typically do not “get” history.

Being Homo sapiens

One way to fail to have a sense of history is not grasping the constancies of human nature. Homo sapiens remain Homo sapiens. Yes, we have varieties in traits—including significant differences in male and female patterns—but we nevertheless conform to strongly persistent patterns across cultures and groups.

One of the selection pressures on our kind is the ability of groups to gain or lose members. This is why I am not a supporter of a strong notion of (genetic) group selection, though I agree that selection more broadly is a multi-level activity. People—and their lineages—can move between groups precisely because our species has such common features that we can adopt the patterns of the new group. Your lineage has gone through different ethnicities just as it has gone through different species.

Cultures or ideologies that adopt a very strongly hierarchical view of human nature—treating different groups as somehow different kinds, which are then ranked—produce myth rather than history. Brahmin (Indic) civilisation had by far the weakest sense of history of the major Eurasian civilisations precisely because its view of humanity was so intensely hierarchical. It did not produce any serious chronicle or work of history until the C12th and even that example had strongly mythic content and form plus it came from a region that had interacted with Islam—a civilisation with a rich tradition of historical writing—for centuries.

Marxism—and its Critical Theory derivatives—promulgate deeply hierarchical views of humans: by class in the case of Marxism; by race, sex, gender, sexuality, etc in the various Critical Theories (Critical Race Theory, Critical Pedagogy, Queer Theory, etc). Hence, all these strains of thought intensely mythologise history. They produce cartoon (simplistic) and caricature (distorted) history to support the overarching historical myth of the transformative future as oppression-free heaven, the past as evil hell, and the present as oppressive purgatory.

This is done by making whichever categorisation of people into different kinds—on the oppressor/oppressed scale—causally dominant. The classic version of this is Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto (1848):

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

Each later Critical Theory derivative puts as causally dominant whatever its particular focus is. Increasingly, since the 1960s, this has extended to denying knowledge is based on anything other than relations to power a la Foucault. Hence knowledge is not discovered, it is “produced”, and everything is socially constructed. Replacing the physical reality of sex with personally constructed gender identity epitomises this.

All this builds a moral and political identity based on the splendour in their heads—their wondrous vision of the imagined future and the righteous behaviour of affirming the same and working for it. Thus, morality is defined as agreeing with them, for the vision in their heads becomes the benchmark of judgement, thus they own morality.

History as contingent events is replaced by myths that support their identity as being moral trumps because of the splendour in their heads. Morality stops being a common feature of humanity that varies by individuals—as history and psychology teaches us1—and becomes the thing whose possession defines progressives as a group, who thus have the duty to shun, shame, isolate those who dissent (and so are immoral).

This monopolising of morality requires the mythologising of history. It requires the replacement of accurate history with conforming and justifying myth, with various groups performing their pre-determined roles.

In Australia, for example, local councils and libraries used to be excellent sources about local history. Now, information about the history of European settlement is vanishing, being replaced by a sparse and sanitised Aboriginal history.

As per Settler-Colonial Theory, European (“white”) settlement has become the evil past (and oppressive present) while Aborigines—as the indigenous inhabitants—have become the moralised noble natives who have the only legitimate history, according to the pre-set mythic roles, including of them living in harmony with nature. This despite the skeletal evidence indicating that not only were Aboriginal societies violent—even by standards of foraging societies—but that violence was inflicted more on women than men, which is a wildly outlier result, as males dominate the victims of violence across human societies.2 That Aboriginal societies were marked by gerontocratic polygyny—young women were allocated as wives to old men, which served to pass information about a dangerous environment, and complex foraging techniques, across generations—may help explain this startling pattern of more female woundings.

The progressive vision also requires the mythologising of the present. If progressives own morality, then dissent must be immoral. If they own morality, then social dynamics must conform to their justifying myths. British commentator Conor Tomlinson provides examples of use of taxpayer funding to promulgate such mythologising into popular entertainment.

As there is no information from the future, their benchmark for judgement—the imagined future—is fact-free. Worse, as past experience is the only information we have for judgement, but the past is evil (i.e. oppression hell)—so illegitimate because it fails to conform to the moral glory of their imagined future—they eliminate useful feedback (such as learning embedded in institutions and heritage) from the past. They also eliminate feedback from the present by anyone who doesn’t agree with them, as they own morality, so dissent is immoral and illegitimate.

They thereby create institutions, societies, a civilisation, of broken feedbacks. Words stop being mechanisms for mutual discovery and turn into instruments of social perfectibility, of identity and dominance.

Meanwhile, morality-as-their-possession justifies progressives’s endless social imperialism, of which DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion)—so control over hiring, resources and speech respectively—is particularly salient. When Western progressives complain about some group using property—capital, masculinity, whiteness, heteronormativity, etc—as their vehicle of control and oppression, that is the iron law of woke projection working overtime. They are complaining about what they do via their ownership of morality—including calling something racist/sexist/transphobic etc until it is destroyed or they control it.

Changes in framing

A second way not to get history is not to grasp how much how people frame things can change across time and space, creating different patterns of action. To understand why people do the things they do, you have to see how the world looks to them.

People from different cultures respond differently to the same incentives because they frame the world differently. As psychologist Jordan Peterson points out in Maps of Meaning, we humans do not cognitively model facts, we model significance, which varies by individuals and by cultures.

Significance, and the framings thereof, varies across time (history) as well as across space (culture). Behaviour that looks bizarre to us makes complete sense if you grasp how people viewed the world, how they framed things. One way to see how changes in framing matter is to see how behaviour changes when a culture changes.

Take gladiatorial combat. It became a centrepiece of the Roman view of themselves. There is a reason the Colosseum was the second largest building in ancient Rome (after the Circus Maximus). Under the Republic, gladiatorial spectacles meant that the citizens who made up the army were inured to violence.

Under the Empire, it enabled Emperors to give citizens a sense of power by collectively deciding who lived or died in front of them. This sense of power supported, rather than threatened, the Emperor. There is a reason why the Colosseum was built by the second dynasty of Roman Emperors.

Gladiatorial spectacle provided Romans with a sense of themselves as a great organising people, putting on these enormous spectacles for their own entertainment. It provided them with a sense of themselves as great imperial people, of what a great thing it was to be a Roman citizen—people and animals from all over the known world fought and died for their entertainment.

Then Christianity arose, which framed the gladiatorial combats very differently. Constantine, as the first Christian Emperor, built his new Rome with a Hippodrome for chariot racing, but with no place for gladiatorial combat. It took around a century or more for the gladiatorial games to disappear—though the fighting animals version lasted another century—but the Christianisation of Roman society also took a long time.

Human nature remains constant, but our framings change, they vary, and this matters. To see our own framings as “natural”, or—even worse—universal, is to be egregiously unhistorical. It is a form of mythologising.

Historian David Starkey puts it with a certain verbal brutality:

3:50: What [the American-founding English populations] agree on is a political culture of self-government and debate. And the problem is post-1970 in America—post-1997 in Britain—we have imported huge populations that do not share those values and are now totally proud of rejecting them. They simply reject them, and resist, and we shouldn't be surprised about this. After all, aren't we told by the left all cultures are equal? But equally what the left will not recognize cultures are also different. It is this insane liberal belief that we're all the same. You know, liberal universalism: that you've got a universal man that's got universal rights. This is infinitely stupid.

It is also deeply ahistorical.

Changes in constraints

A third way not to get history is not to grasp what a difference changing constraints can make. The history of money provides a nice example of this.

Yes, humans have used an amazing variety of things as money. Nevertheless, by far the most significant monetary medium across history has been silver. Gold was also used, but nowhere near as extensively—the full-deal, multi-national, gold standard lasted from 1873 to 1914. Because we live in an age where states can declare pieces of paper—or even plastic—to be money, it is easy to fail to grasp how valuable (and often difficult) having access to enough silver was.

For states with very limited administrative capacity, and fuzzy borders, silver made it much easier to have effective monetisation of transactions precisely because it was both durable and readily accepted while being much more plentiful than gold. Monetisation greatly simplified revenue collection, and encouraged trade—and so the revenue therefrom—by reducing transaction costs. (Or, as I like to think of it, transaction friction.)

What folk often don’t get is how slow the process of monetisation was, even in European societies. It literally took centuries, as rural localities continued to engage in lots of in-kind exchanges.3 The C19th is the first century where the overwhelming majority of transactions were monetised across European (and neo-European) economies.

How can we tell? From the beginning of the C19th on, trends in prices become completely divorced from population shifts. Shifts in the price level4 across the C19th, and up to 1914, are entirely driven by the use of gold (and silver) in exchange for output of goods and services.

When there were gold rushes, there were mild inflationary periods in gold-standard economies—the price level rises, as money loses value relative to output because the use of gold (directly or via banknotes) in exchange rises faster than output of good and services. When economies shift to the gold-standard, there are deflationary periods—the price level falls, as the monetary demand for gold increases relative to the supply of gold for monetary purposes. This drives up the value of gold—so money—relative to the output of goods and services, driving down the money-prices of goods and services.

If strong deflationary expectations set in, people delay transacting—their money will buy more later—so spending, and thus incomes, fall; so the burdens of debt rises; so bankruptcies and financial collapses increase; creating a debt-deflation downward spiral. This happened in the early 1890s and in the early 1930s. A surge in gold production—the Klondike and Kalgoorlie and other West Australian gold rushes, building on the continuing Witwatersrand Gold Rush—pulled the gold-standard economies out of the 1890s Depression.

In the early 1930s, the Bank of France turned the revived gold standard into an economic death spiral by taking more and more gold out of the global monetary system, so continually driving the value of the remaining gold in the monetary system up, and so prices continually down. A process that the US Federal Reserve did nothing to counteract. Thus, leaving the downward-spiral gold standard pulled economies out of the 1930s Depression.

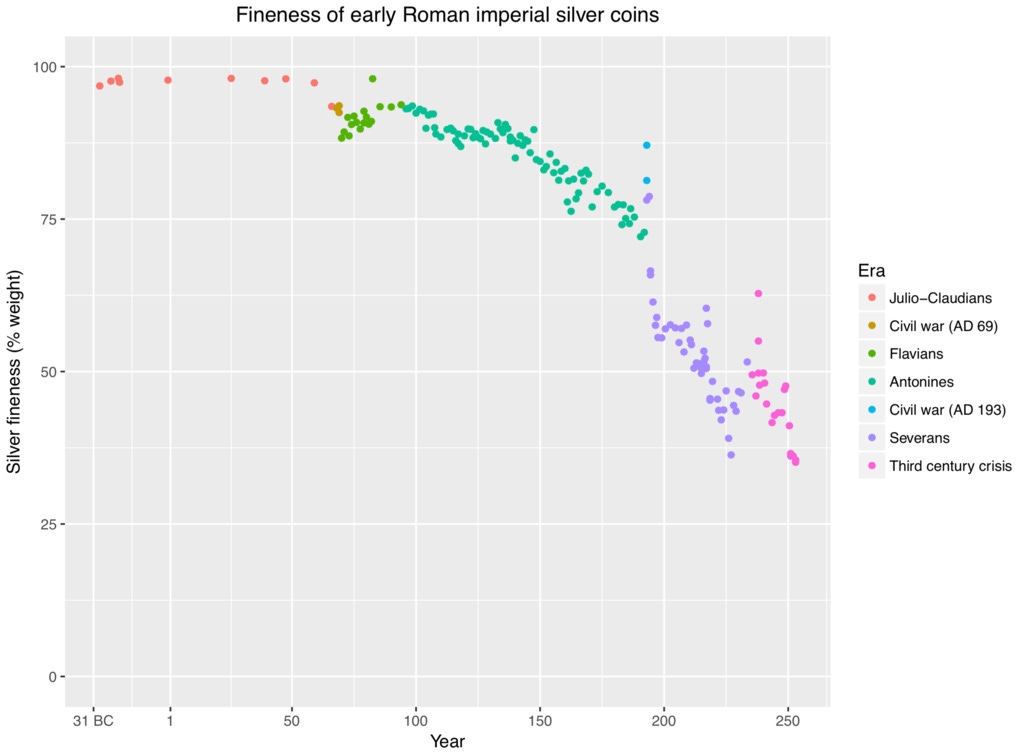

Going back to before monetisation had reached C19th levels, if a state had silver mines, then it could readily import more goods than it exported, as silver was so readily accepted in exchange for imports. Classical Athens, Imperial Rome prior to the Crisis of the Third Century—which was a phenomenon across Eurasia and was significantly driven by the collapse in Roman silver production driving down trade revenues—and the Spanish Empire, were all examples of this dynamic.

If a state had to import its silver, then it was strongly preferable to export more goods than it imported, so that the silver to support monetisation would flow in. Muscovy and Imperial China were examples of this dynamic.

Favouring exports over imports made sense in the absence of domestic sources of silver, given that the monetisation of economies was an on-going process. It is hardly likely to be an accident that the post-medieval European school of thought that most diverged from the mercantilism of the time was the School of Salamanca, in the silver-exporting Spanish Empire. Sneering at our predecessors—for example, for being “stupid” mercantilists—because you do not understand the constraints they were labouring under, is not a good look. It is deeply anti-historical.

Conclusion

There is nothing inherent or natural in having an historical perspective. On the contrary, thinking of events as embedded in an eternal present is much more natural.

Only a relatively small number of civilisations developed a strong historical sense—primarily Classical Greece and Imperial China. Classical Greece passed a sense of history on to Rome, from whence it was passed on to Islam. China passed an historical sense onto Korea, Vietnam and Japan. After dwindling to chronicles in the medieval period, the revival of Classicism in the Renaissance passed an historical sense onto post-medieval Christian Europe and so to the modern West.

With the rise of Critical Theory and its derivatives, we can see Western progressives replacing a sense of history with egregiously self-serving myth. This is a profound attack on an informed sense of ourselves, of others, of the past, of the present, and of a sense of future possibilities. It is a profound attack on history, on having a genuinely historical awareness. It has a great deal to do with the march of toxic stupidities in our time.

The shift away from rule of law—whose fundamental principle is treat like cases like—to anarcho-tyranny, to imposing ever harsher burdens on the law-abiding and ever weaker ones on the “marginalised”, represents a grotesque failure to understand the lessons of the past. It represents the stupidity of the moral and cognitive arrogance of the Western-progressive mindset at its most egregious. No wonder the netizens of China—a society and civilisation with a profound sense of history—regard the baizuo with such contempt.

References

Donald E. Brown, Hierarchy, History & Human Nature: the Social Origins of Historical Consciousness, University of Arizona Press, 1988.

Christophe Darmangeat, ‘Vanished Wars of Australia: the Archeological Invisibility of Aboriginal Collective Conflicts,’ Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2019) 26:1556–1590. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10816-019-09418-w.pdf

Anthony Edo & Jacques Melitz, ‘The Primary Cause of European Inflation in 1500-1700: Precious Metals or Population? The English Evidence,’ CEPII Working Paper No 2019-10 – October. https://www.cepii.fr/PDF_PUB/wp/2019/wp2019-10.pdf

Douglas A. Irwin, ‘Did France Cause The Great Depression?,’ Working Paper 16350, September 2010. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16350

David Hackett Fisher, The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History, Oxford University Press, 1996.

Irving Fisher, ‘The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions,’ Econometrica, (1933) 1 (4): 337–357. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/debt-deflation-theory-great-depressions-3596

Tim Kaiser, Marco Del Giudice, Tom Booth, ‘Global sex differences in personality: Replication with an open online dataset,’ Journal of Personality, 2020, 88, 415–429. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jopy.12500

Joe L. Kincheloe, Critical Constructivism, Peter Lang, [2005] 2008.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830: Volume I, Integration on the Mainland, Cambridge University Press, [2003] 2010.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830: Volume 2, Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands, Cambridge University Press, [2009] 2013.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Colin Pardoe, ‘Violence and warfare in Aboriginal Australia,’ in Geoffrey Clark, Mirani Litster (eds), Archaeological Perspectives on Conflict and Warfare in Australia and the Pacific Book, ANU Press, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Colin-Pardoe-2/publication/359093125_Violence_and_warfare_in_Aboriginal_Australia/links/6316dca6acd814437f0909aa/Violence-and-warfare-in-Aboriginal-Australia.pdf

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

A. Hingston Quiggin, A Survey of Primitive Money: The Beginnings of Currency, Routledge [1949], 2019.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: A History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale University Press, 2009.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021), 46(1):1-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354584406_Polygamy_the_Commodification_of_Women_and_Underdevelopment

Scott Sumner, The Midas Paradox: Financial Markets, Government Policy Shocks, and the Great Depression, Independent Institute, 2015.

Adam Waytz, Ravi Iyer, Liane Young, Jonathan Haidt & Jesse Graham, ‘Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle,’ Nature Communications, 2019 Sep 26;10(1):4389. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6763434/

Fei Xiaotong, From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society, trans, with an introduction and epilogue by Gary G. Hamilton and Wang Zheng, University of California Press, 1992.

As a much-cited study found: “these findings demonstrate that liberals and conservatives differ not in the total amount of moral regard per se but rather they differ in their patterns of how they distribute their moral regard.”

Even if the depressed skull fractures were in part self-inflicted mourning rituals, it would still be a startling level of violence against women.

As late at the first half of the C20th, Chinese villagers would deliberately go to the local market town to engage in monetary exchange with someone else from the same village, as their village—with its network of personal connections—was not the place for monetary exchanges.

The price level is effectively the price of money in output—in goods and services—terms. A rising price level means that money is losing value (inflation). A falling price level means that money is gaining value (deflation). Interest rates are NOT the price of money, they are the price of credit.

You omitted the shibboleth (and mythical construct, and outrageous lie) - the right side of history. Anyone spouting that is as fraudulent a speaker as a televangelist (and no doubt shares that unshakeable belief in their own righteousness).

I would suggest that Islam picked up it's historicity from Judaism. There is a reasonable case to be made that Islam is a heretical sect of Judaism and follows the idea throughout the Qur'an of the narrative in the Old Testament with many additions and historical inaccuracy.