Human agency and the falsity of Equalitarianism

You inherit a lot more from your parents than genes.

So, Nathan Cofnas did a post, to which I wrote three responses — here, here, and here — to which he responded. Then I did another post. This is me wrestling some more with heritability. It is, in part, a response to Richard Hanania’s post.

First, a confession: I am not very interested in race. I am much more interested in human dynamics in general and race is generally not a factor of much importance, even though ancestry does matter in various ways.

The US has a history where folk of different continental origin played different roles in the American polity — settler-citizen; conquered locals; slave; resented immigrant. This has generated an obsession with race that Americans do not seem able to shake.

Yet, what became the modern concept of race — based on continental or sub-continental regions — was developed well before Columbus, to justify slavery. It was developed by Muslim intellectuals, particularly in al-Andalus and the Maghreb.

As Muslims systematically enslaved both Sub-Saharan Africans and Europeans, Muslim writers intellectualised both anti-white and anti-black racism to justify systematically enslaving fellow children of Allah. (The Romans, not being moral universalists — and enslaving lots of folk who looked like them — did not feel the need to generate such justifications.)

The analytical tropes of Muslim intellectuals were taken up (or re-invented) to justify European slavery of Sub-Saharan Africans in the Americas and then extended to both explain, and justify, European global dominion. There was nothing remotely scientific in any of this, despite pretensions to the contrary. Indeed, there was an entire stream of commentary about the alleged salience of race that was explicitly anti-Darwinian.

The development of Darwinian evolutionary biology, Mendelian genetics, the discovery of DNA, the mapping of the human genome, all seemed to hold out hope that there could be a scientific basis for taking race seriously.

This has proved to be wildly overblown. And yes, I am aware of the moral and political pressure against any form of genetic hereditarianism.

A key analytical problem is human cognitive plasticity. As evolutionary biologists Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein say:

Humans are not blank slates, but of all organisms on Earth, we are the blankest (p.146).

Our cognitive plasticity is, in a sense, our species strategy. It is why there is no single human niche, but an ever-expanding cornucopia of them. It is why we have such biologically expensive children and risky childbirths. Our walking-upright pelvises limit how large our infant heads can be, hence the need for very long childhoods to grow and train brains that do not settle into adult form until our 20s.

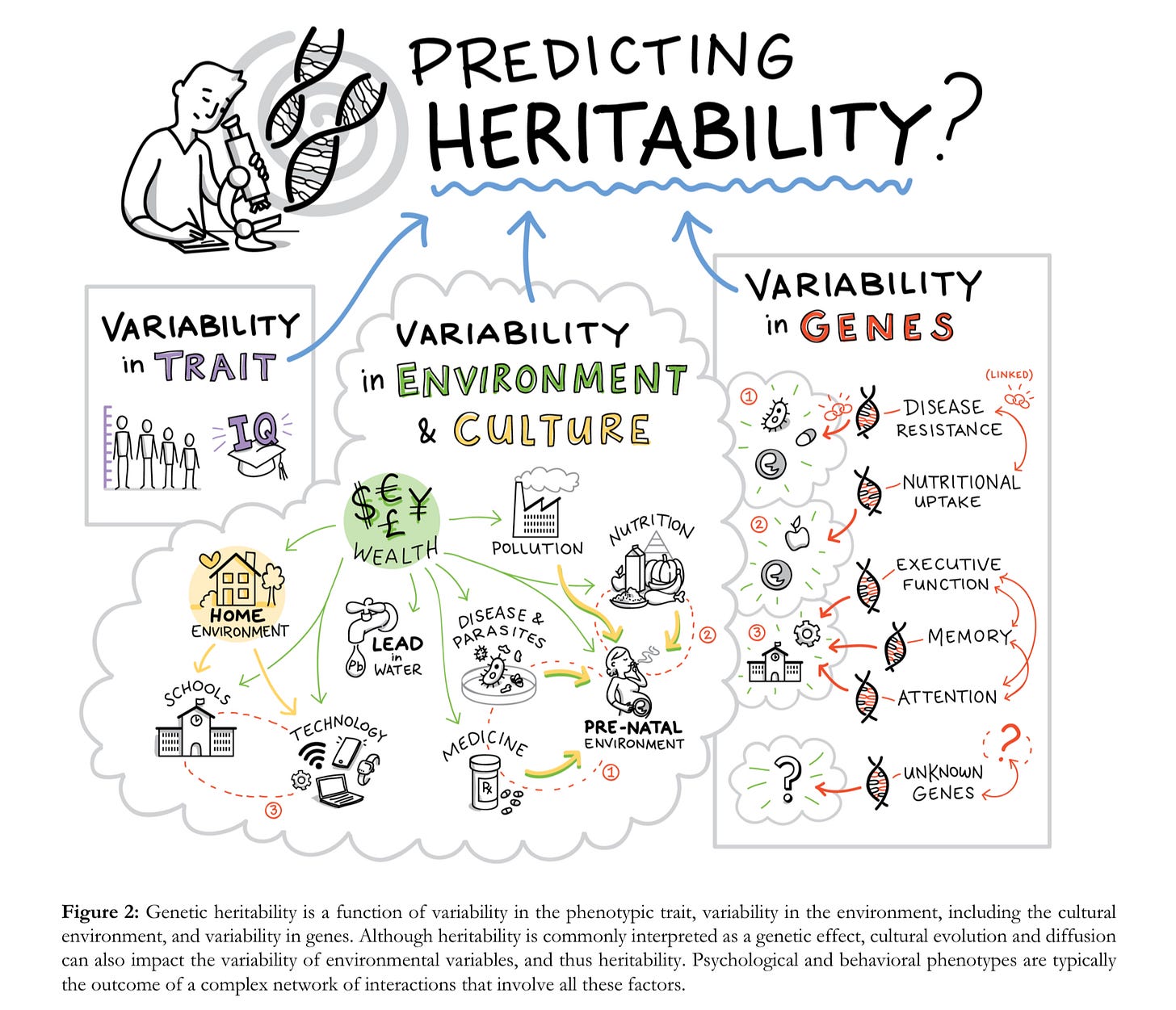

An excellent discussion of the sheer complexity of interactions between genes and environment among humans — and the difficulty in teasing out how strong genetic effects are — is here. Intelligence, for instance, appears to be both heritable and malleable via gene-environment interplays.

If one set of human lineages is persistently better at something than another that does not automatically mean that they have more favourable genetics. It may be they have less favourable genetics but a more favourable environment and/or more successful patterns of human action.

Human social action is too complicated for folk to be able to say persistent difference = genetic causes. Just to add to the complications, human choices can have genetic effects. That is the basis of gene-culture co-evolution. But human choices can have even more direct genetic effects. It is quite clear that 1400 years of marrying first and second cousins have had adverse genetic effects in the Middle East.

When looking at the outcomes of human groups yes, everything social is emergent from the biological. Everything we do is enabled (and constrained) by our biology. But it is also affected by our physical environment, both natural and human-made.

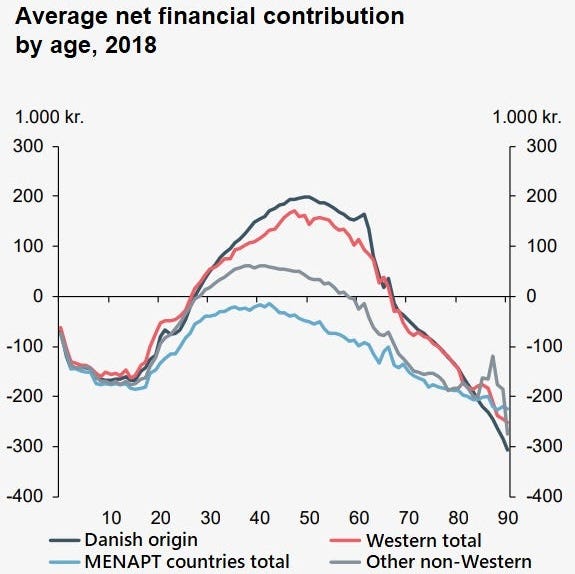

Moreover, we are not only the cultural species par excellence, we are the technological species par excellence. The concept of the Anthropocene is not a silly concept. The above chart includes consequences of our technology feeding into heritability.

Genetic and cultural evolutionary pressures on populations do vary. In some continental or sub-continental regions, the pressures of the environment were unusually high. Notably in Sub-Saharan Africa where we evolved, so a lot of parasite, pathogens, predators and mega-herbivores co-evolved with us; and in Australia, which has an unusually harsh and poisonous environment. Conversely, selection pressures where we were “vermin” — a (self) introduced species in eco-systems with no local species that had co-evolved with humans — would be more skewed towards dealing with other humans. The evolutionary trade-offs — both cultural and genetic — in those harsher environments may be a relative disadvantage for their descendants in more human-dominated environments. But, even if that is so, it is not enough to rescue the conventional views of race.

Flaws in mainstream economics

A problem for mainstream economics is that Homo sapiens are not — except in narrowly conceived domains — Homo economicus. It is precisely because we are the normative species that we are far more successful than our Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) cousins. Put them in a behavioural lab and get them to play strategic games, and they will be close to perfect exemplars of Homo economicus.

We are not such, precisely because we are far more normative, to our enormous evolutionary advantage as it enables our extraordinary levels of non-kin cooperation. We exemplify the social conquest of the Earth: how the phylogenetically rare, but enormously evolutionarily successful, social species dominate so much of animal biomass.

We are not only more normative than our Chimpanzee cousins, we are also far more active believers. We are the religious ape, which enables us to generate devoted agents: folk who stubbornly resist trade-offs against things deemed sacred, to the advantage of group cohesion. Being the self-conscious ape, we have evolved mechanisms to handle being self-conscious: most notably religion (and its substitutes) as well as wisdom traditions.

Indeed, when it comes to sabotaging our contemporary (in)ability to think accurately about differences between human groups, mainstream economics has much to answer for. As Kenneth Pollack notes in Empires of Sand:

…until relatively recently, Western economics and management theory took as a bedrock assumption that universal factors such as the availability of technology and the profit motive would produce similar organizations and methods of operation in any business regardless of cultural factors.1

That turns out to be simply not true:

… is not the only study to find that economic and business practices in the Arab world are heavily infused by the same culturally driven patterns of behavior as their armed forces, and that they tend to create similar hindrances. This is striking because, until relatively recently, Western economics and management theory took as a bedrock assumption that universal factors such as the availability of technology and the profit motive would produce similar organizations and methods of operation in any business regardless of cultural factors. This has been challenged broadly by new studies of the impact of cultural preferences on organizations, management, and leadership, such as the massive Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) study of such practices in 62 different countries. The GLOBE study found that societal culture had a far greater impact on leadership, management, and organizational behavior than market forces and industry effects (i.e., industry-wide practices across societies). This and other such studies have increasingly demonstrated that, despite the Darwinian competition of the marketplace (akin to the competition of combat), organizations function very differently in different societies. They have found that this holds true even for businesses nominally owned by foreign entities, which have to take on the patterns of behavior of the host country to survive and thrive.

This is because the Loury principle — social relations before economic transactions — turns out to be correct. Our exchanges with others are embedded within webs of connection, norms and expectations.

Family structures are very important in generating these norms and expectations. They are at least as important as religion. As Pollack writes:

Culture is both the practice of how things are done in a society and the values that suggest how things should be done by the members of that society. Among the most important and discernible elements of a culture are its religion, language, family life, hierarchies, and other groupings. These are simultaneously sources of culture, products of the culture, and methods for the transmission of culture.

Once such patterns of norms and expectations are embedded in, and reinforced by, human behaviour, they can be remarkably persistent, generally evolving quite slowly, with strong patterns of persistence. The power of culture — interacting with ecology and family/kin group structures — is a large reason why, for instance, Malay, Islander and South Asian Islam [India and Bangladesh] are rather different beasts than [Greater] Middle Eastern Islam [Morocco to Pakistan].

It is worth stopping and considering how inadequate — if one is being polite, pernicious crap,2 if one is not — so much of the economic analysis of migration is. The presumption of mainstream economics that humans are interchangeable rationally optimising agents whose networks of connection are of minimal importance is false thrice over. Alas, it encourages us to think about human groups as also interchangeable, which is both a false and highly misleading way to think about migration, for instance.

Culture as life strategies

In line with the social being emergent from the biological, it is useful to think of culture as embedded life strategies. The claim of equalitarianism that there are no differences between human groups that would lead to different social outcomes is nonsense on stilts. And it would be nonsense on stilts even if there were no genetic differences between human groups.

What equalitarianism ends up claiming — in the light of differing average outcomes between groups — is that human agency is enormously unevenly distributed between human groups. This is required to sustain the nonsense claim that Western societies are structures of oppression. A claim that, at best, is a set of delusions, at worst a series of lies.

For, without hugely uneven distribution of human agency, differences in social outcomes will not be mere consequences of patterns of externally-imposed disadvantage (“oppression”). They will be, in large part, a result of differences between human groups, including their inherited differences. Inherited differences that may, or may not, be significantly genetic but will be significantly cultural.

In Australia, the difference between the highly successful integration into Australian society of Christian Lebanese — who have produced a State Governor, a State Premier, a Lord Mayor of Sydney — compared to the much less successful integration of Muslim Lebanese — who are most known for gang violence — provides a particularly stark example of the importance of culture.

Hereditarianism, if it is about inherited differences, is not merely about genetic differences. It is entirely possible for it to not be about genetic differences much at all. Equalitarianism is false, not despite the fact that we are so much the cultural species, but because we are so.

References

Scott Atran, ‘“Devoted Actor” versus “Rational Actor” Models for Understanding World Conflict,’ Briefing to the National Security Council, White House, Washington, DC, September 14, 2006. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6801978.pdf

Eric Chaney, ‘Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present,’ Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2012, 363-414.

Eric Chaney, ‘Religion and Political Structure in Historical Perspective,’ Working Paper, October 2019.

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989], 1994.

Jeremy Ginges, Scott Atran, Douglas Medin, and Khalil Shikaki, ‘Sacred bounds on rational resolution of violent political conflict,’ PNAS, May 1, 2007, vol. 104, no. 18, 7357–7360.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353.

Garett Jones and W. Joel Schneider, ‘IQ in the Production Function: Evidence from Immigrant Earnings,’ Economic Inquiry, (2010) 48, issue 3, 743-755.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Mark Horowitz , William Yaworsky & Kenneth Kickham, ‘Whither the Blank Slate? A Report on the Reception of Evolutionary Biological Ideas among Sociological Theorists,’ Sociological Spectrum: Mid-South Sociological Association, (2014) 34:6, 489-509.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

C.F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa, & C. Camerer, ‘Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions.’ Scientific Reports, 2014, 4, 5182.

Bruno Sauce and Louis D. Matzel, ‘The Paradox of Intelligence: Heritability and Malleability Coexist in Hidden Gene-Environment Interplay,’ Psychological Bulletin, 2018 January ; 144(1): 26–47.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Kenneth M Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Daniel N. Posner, ‘The Implications of Constructivism for Studying the Relationship Between Ethnic Diversity and Economic Growth,’ 2004.

Robert J. Richards, Was Hitler a Darwinian?: Disputed Questions in the History of Evolutionary Theory, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Hammad Sheikh, Jeremy Ginges, Alin Coman, Scott Atran, ‘Religion, group threat and sacred values,’ Judgement and Decision Making, (2012) 7(2), 110-118.

Hammad Sheikh, Jeremy Ginges, and Scott Atran, ‘Sacred values in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict: resistance to social influence, temporal discounting, and exit strategies,’ Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, September 2013, 1299, 11–24.

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136.

Emmanuel Todd, The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems, (trans. David Garroch), Basil Blackwell, 1985.

R. Uchiyama, R. Spicer, M. Muthukrishna, ‘Cultural evolution of genetic heritability,’ Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2022;45:e152.

Bo M. Winegard, Cory Clark, Connor R. Hasty, Roy F. Baumeister, ‘Equalitarianism: A source of liberal bias,’ Journal of Open Inquiry in Behavioral Science, 2023.

Kenneth Pollack uses culture (in his words as): the anthropological sense of learned, shared values and patterns of behavior developed by a community over the course of its history.

Badly handled migration can often be a form of domicide, where communities and heritages get replaced. We can currently see this happening in London. Mass migration fractured the American Republic over its fault-line of slavery in the 1860s, as Robert Fogel explains in his Without Consent or Contract.

We live in a world where physical and behavioral differences between human population groups are observable. The question then arises, what are the causes of these differences? To me, the most important information you would want to know is - what is the nature of the these groups and why do they exist? You would need to know this to set a baseline of assumptions about equality. If genomic evidence shows that these groups were caused by a intermixing of homo sapiens of various subspecies (Neanderthal, Denisovans, etc.), genetic bottlenecks and selection pressure, is it reasonable to assume that these groups would all have the exact same brain structure? It seems like the default hypotheses should be that there are genetic differences in the brains between groups, but culture/social factors also play a major role in the overserved behavioral differences.

The idea that all humans are part of the same homogenous group, and that the differences between us are superficial seems to come from the idea of human exceptionalism - that we are an entirely separate form of life than other animals on this planet and not subject to the same evolutionary rules.

"Equalitarianism is false."

I tend to agree, but very tricky proposition to sell to the Christian cultures of the west from which this ideology sprung, and not, I would argue accidently. As you have said before, it is the socialization of the spiritual belief in equality before God.