Immiseration cycles and monetary surges

David Hackett Fischer’s ‘The Great Wave’.

[It turns out I had not entirely thought my thoughts through to the end when I wrote this review. I now have, see this post.]

Before discussing David Hackett Fischer’s 1996 book The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History, I am going to do what he does not do and lay my analytical cards on the table upfront.

The Great Wave would be a better book if he had. David Hackett Fischer has this unfortunate habit of adding in crucial bits of the analysis later in the text. A failing compounded by being rather uneven in his application of said factors.

Immiseration cycles

The Rev. Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) is well known for having developed his rather grim analysis of the pressure of food on population. Malthusian analysis works just fine for human populations, if you remember three things:

the rate of technological change matters;

biological beings operate in niches—competition for and between niches is a fundamental fact of biological, and social, selection; and

Homo sapiens are the niche-creating species par excellence.

So, (sedentary) farming displaced (nomadic) foraging because farming niches were smaller across various dimensions—most obviously land area, but also in skills required and easier child supervision—than foraging niches. Moreover, as farming involved making food, farming niches multiplied well beyond them being smaller than foraging niches.

Hence, farming—and later pastoralism—has been displacing foraging ever since farming first developed around 11,000 years ago. A process that is still going on in various localities, with the last continent the process of farming and herding displacing foraging and foragers reached being Australia, where it started in 1788 with British settlement.

Famines occur when there is not enough food to sustain the currently occupied human niches. If it persists, mass starvation results due to a dramatic drop in the number of food-sustainable human niches.

An immiseration cycle is when the resources going to lots of people shrink—i.e., human niches shrink in size. Karl Marx was correct in that we can see immiseration cycles across history. He was—as he almost invariably was—quite wrong about the causal mechanism involved. Immiseration cycles have nothing to do with the increasing production of capital. On the contrary, increasing use of capital is a great barrier against immiseration by increasing production.1

Immiseration cycles are driven by population rising faster than productive use of land. In other words, by land/population ratios.

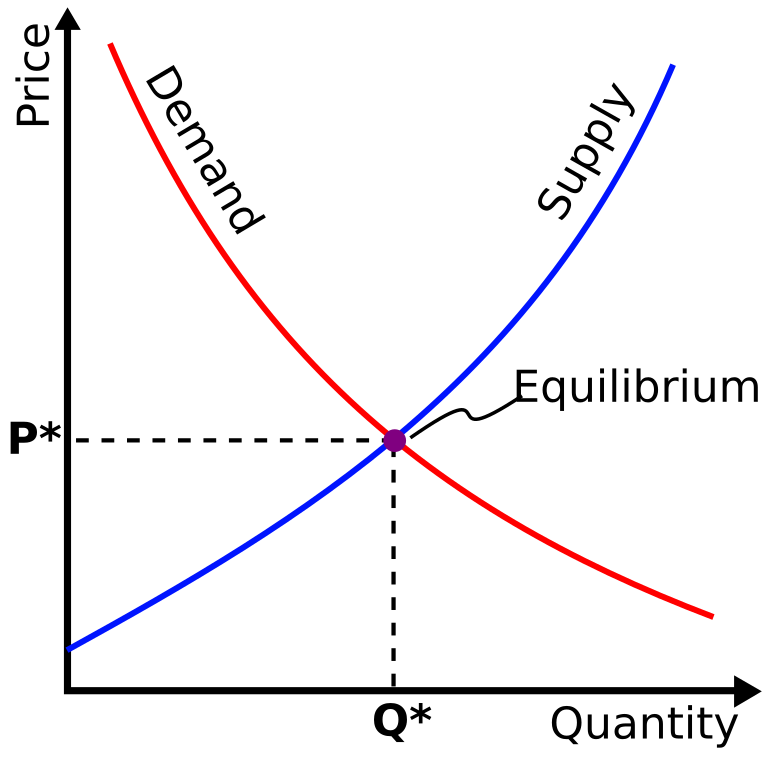

In pre-industrial societies, if the population increases faster than productive use of land, various predictable results follow. Food prices rise, both from increased demand and as more and more marginal land is brought into production, raising food production costs. In other words, the demand curve moves “rightwards” while production moves up the “right-sloping” supply curve.

The output-value of wages—“real” wages—fall as labour gets more plentiful and food prices rise. Land gets relatively more valuable, so rents rise. Capital gets relatively more valuable, so interest rates rise. These are predictable structural responses.

The more narrowly land and capital are held, the more inequality rises from the increased returns to land and capital. Indeed, as the costs of land and capital rise—and distress increases—the concentration of ownership of both land and capital is likely to increase, further increasing inequality. Material stress—including the sharpening of status differentiations—makes family formation harder and violence a more attractive strategy.

Once you realise that rising food prices =/= inflation and that Fischer is describing immiseration cycles, much is clarified:

Once again, the most rapid movements occurred in the price of energy and food.

…

The smallest gains were in the price of manufactured products, which lagged behind as they had done in every other great wave. (p.123)

Because food and energy was more constrained than manufacturing. Something he points out later.

David Hackett Fischer discusses the grim political reality that the politics of starvation are very different from the politics of hunger. As was continually demonstrated across history—up to, and including, the terror-famines of Marxist regimes2—starving folk are no threat to a ruling regime. People who are starving are too weak, and too food-obsessed, to revolt.

Hungry people, by contrast, are angry people. We are all familiar with folk being hungry-angry—hangry. Across the C18th, hangry mobs turned out to be perennial sources of revolt and rebellion.

The harvest failures of the C18th did not have the mass starvation effects of earlier harvest failures. The increase in the quantity of water transport—more ships and barges—and in the reach of water transport—more canals—coupled with increased welfare efforts (both public and private) shielded folk from starvation.

These welfare efforts were more effective due to the increased reach and capacity of water transport. Hackett notes the welfare efforts—and the reality of increased trade in grain—but not why the grain trade had so increased in reach and capacity that it was much more successful at ameliorating harvest failures.

The ironic result of this increased capacity and effort was that harvest failures became more socially and politically destabilising, not less. The Bourbon monarchy was far more threatened by mass hunger in France in the 1780s and 1790s than was British rule in Ireland by mass starvation in the 1840s. (Irish emigration to the US and elsewhere also had a pacifying effect.)

Immiseration cycles occur across history. They are a particular problem for empires, as empires impose order across large areas. The creation of such order typically means an increase in prosperity, so folk start having more children.

The increase in population then pushes on available resources. Increased conflict over resources can then weaken, or even collapse, the empire—for instance, if peasant revolts interact with increased elite struggles over available elite niches.

Immiseration cycles were a factor in the Chinese dynastic cycle. Modern scholarship allows us to map the archetypal dynastic cycle in Chinese history:

Population expands due to peace and prosperity in a unified China. This pushes against resources—mainly arable land—creating mass immiseration, peasant revolts and falling state revenues.

The number of elite aspirants expand but elite positions do not, leading to disgruntled would-be elites who provide organising capacity for peasant revolts.

Bureaucratic pathologies multiply, leading to a more corrupt, less responsive, less functional state apparatus, eroding state capacity and increasing pathocracy (rule by the morally disordered). Late dynastic imperial bureaucracies could be astonishingly corrupt and dysfunctional.

We are currently going through an immiseration cycle as urbanisation and migration—even more so if tied to restrictive land-use zoning—is driving up populations faster than the productive use of land (specifically for housing). One that is interacting with metastasising bureaucracy and elite over-production [or perhaps not]—so, very Chinese.3 Hence the increasing political alienation, manifesting in rising support for national populism and various riots and protests (including protests that become riots).

Money and prices

Fischer argues in terms of aggregate supply and demand:

The prime mover of this price-revolution was the increasing pressure of aggregate demand, caused by an acceleration in the growth of population. (p.123)

Rising demand only causes sustained rise in prices if supply is constrained. Something Fischer again points out later.

Fischer also does not think through the nature of transactions in a monetised society. Yes, aggregate demand is total spending. But folk have to have something to spend, to transact with, otherwise prices in aggregate cannot go up.

When you are tracking the price level, you are tracking the output—i.e. goods and services—price of money. If there has been a general increase in the price level, then money has got less valuable relative to the output of goods and services. If this process continues, then money is continually getting less valuable relative to output. This must mean that:

the money supply has gone up; or

the rate at which money is being used has gone up; or

the use of substitutes for money has gone up; or

some combination of the above.

Thinking this through both clarifies what particular evidence is—or is not—telling us and what evidence to look for to disentangle various phenomena.

The classic substitutes for money are (1) in-kind transactions and (2) IOUs. One of the features of later medieval and early modern Europe was the development of sophisticated systems for using IOUs as payments—such as bills of exchange. The increased use of IOUs as a means of payment has been a continuing pattern, with electronic transfer at point of sale (EFTPOS) being the latest manifestation of this.

We talk of having “money in the bank”. We don’t. There is no set of notes and coins the bank is holding that is “yours”.

What we have is credit with the bank. These are Bank-OUs on which the bank pays interest. They are an asset for us and a liability for the bank. These Bank-OUs can be used as payments. We transfer (as “money”) the Bank-OUs to the person we are purchasing from as a means of payment. What were Bank-Owes-Us become Bank-Owes-Them.

This is why I dislike defining money as a medium of exchange: credit is also a medium of exchange. I prefer to talk of a medium (or means) of payment. After all, one can also pay off debts and purchase assets with a means of payment. When folk say “money is credit” what they are identifying is that Bank-OUs are a medium of payment denominated in a unit of account.

Across most of European history, silver has been the main monetary metal, followed by gold. Increases in the supply of either had an inflationary effect—reducing the output-value of money—whenever the increase in supply of, so use of, monetary metal was greater than the increase in output of goods and services. One of the weaknesses of David Hackett Fischer’s analysis is that he cites silver and gold supply figures at various times without asking sufficiently often what is also happening to output at that time.

Fischer treats supply of silver as the crucial factor in assessing monetarist explanations of price movements, when it is the use of silver as money relative to output of goods and services that matters. If surges in the supply of silver being used as money match surges in output, there will be no inflationary effect. In a monetised economy, (money-)prices overall can only go up if there is the money (or money substitutes) to enable (money-)prices to go up.

Monetarist explanations of immiseration cycles do, indeed, make no sense. Monetarist explanations of relative shifts in the output-value of money make much more sense: especially if one separates use of money in exchange from holding money as an asset.

The fundamental problem of David Hackett Fischer’s analysis is he fails to distinguish immiseration cycles from monetary patterns. He therefore confuses inflationary pressures with scarcity pressures.

Fischer apparently sees inflation as “resource scarcity per person”. Or, in admirer Rudyard Lynch’s words (20:45): “inflation isn't a pure proxy for population growth, it's really resource scarcity per person”

Yes, increased scarcity relative to population can drive up various prices. Nevertheless, demand cannot manifest in a monetised economy without the money to express it, except by increased use of substitutes for money. This is not some weird inference from economic theory, it is simply the structural features of what is required for transactions to occur in a monetised economy.

Trying to connect population increases and inflation seems to be a bit of a recurring sin of historians. Fischer argues that population growth drives inflation, as he confuses immiseration cycles with inflationary patterns. Meanwhile, Sir Niall Ferguson argues that immigration ameliorates inflation. Any economically knowledgeable Australian is going to be sceptical of any connecting of population growth with inflation, as Australia’s population has increased dramatically over time, displaying no correlation with inflation at all.

Food prices going up faster than the general price level are an expression of scarcity pressures, not inflationary pressures. The effect of such scarcity pressures may lead to inflationary choices by monetary authorities. But inflation itself is a monetary phenomenon.

David Hackett Fischer accepts that hyperinflations have monetary explanations, as they do. So, if money is losing output-value fast enough, that has a monetary explanation, but if it is losing value at some indeterminant lower rate, it doesn’t?

Still useful

With this clarification of socio-economic dynamics, there still much to learn from The Great Wave, though its scholarly reception was mixed.

Sociologist and economic historian Andre Gunder Frank wrote a scathing review. Sociologist Thomas Ford Brown is rather kinder, but finds the post-1820 cases do not fit with the dynamics of the previous patterns: not all that surprising.

Brown points out that shifts in the supply of money-as-coined-bullion relative to commodities—which applies across jurisdictions—differs from money-as-debased-currency—which applies in a particular jurisdiction. He provides a helpful summary of Fischer’s cycles:

Each wave begins with a long inflationary period. Fischer calls these the Medieval Price Revolution (1200-1320), the 16th Century Price Revolution (1520-1620), the 18th Century Price Revolution (1720-1820), and the 20th Century Price Revolution (1896-present). Price revolutions are followed by long periods in which prices remain relatively stable: Following the Medieval Price Revolution, the Equilibrium of the Renaissance. Following the 16th Century Price Revolution, the Equilibrium of the Enlightenment. Following the 18th Century Price Revolution, the Victorian Equilibrium.

Brown also points out that the (much higher) inflation of the C20th was much less socially disruptive than the (much lower) inflation of previous periods. This comes from Fischer failing to realise he is dealing with immiseration cycles interacting with inflationary episodes.

If the immiseration cycles lead monetary authorities to engage in inflationary policies, there will be a connection. But, as the immiseration cycles do not cause inflation then, if there is any sort of congruence, something else is going on than what Fischer is claiming.

The price revolution of the C20th is simply not connected to some general immiseration cycle—indeed, for most of the C20th and into the C21st, very much the opposite was happening in many parts of the world. Hence the lack of connection of inflation to social disruption. Indeed, severe deflation—as in the early 1930s—was much more disruptive.

Severe deflation means collapsing spending, so collapsing incomes, so rising debt-burdens, so surging bankruptcies and financial collapses. But, as economic historian John Munro points out, Fischer ignores deflationary episodes, even severe or persistent ones, such as those during the “bullion droughts” of the C15th or the 1873-1896 deflation. (Which was also something of a “bullion drought”, as it came from a series of large economies shifting to the gold standard, driving up the monetary use—so the output-value—of gold, so driving down prices denominated in gold, until the late C19th surge in gold production from the Klondike, Kalgoorlie and Witwatersrand gold rushes provided some re-balancing.)

More recently, the c.1970 onwards flattening of wages in the US, and the c.1985 onwards (accelerating after 1997) rise in shelter costs—rents and house prices—is, via surges in migration, generating an immiseration cycle in the US, the UK and elsewhere: that is disruptive. It has, however, very little to do with inflation.4 Yes, the post-Covid inflation burst has aggravated the immiseration pressures, but the Great Moderation is genuinely a thing and it is the underlying immiseration pressures from the interaction between migration and restrictions on land use and housing construction that are generating political pressures.

In his review of The Great Wave, economic historian John Munro is more measured in his language than Frank, but much more detailed in his criticisms, which amount to a dismantling of Fischer’s thesis about inflation and price revolutions:

Though I am probably more sympathetic to the historical concept of "long-waves" than the majority of economists, I do agree with many opponents of this concept that such long-waves are exceptionally difficult to define and explain in any mathematically convincing models, which are certainly not supplied here. For reasons to be explored in the course of this review, I cannot accept his depictions, analysis, and explanations for any of them.

At first, I could not get my head around the apparent mishmash in Fischer’s presentation of medieval patterns. But when Fischer moves on to the 1470-1650 Price Revolution, what he is saying became clearer. He is running together immiseration cycles—which definitely happen and are matters (basically) of population/land ratios—and shifts in the price level.

At first, Fischer appears not to be aware of the massive surge in the output of the Central European silver mines from the late C15th onwards, due to developing liquation to separate out silver from other metals and (water and horse-powered) piston pumps to pump out the water, but it turned out he was under-estimating their effect.

Late medieval silver mining is a classic cautionary tale about the difference between slave production in a unitary state (imperial Rome) and skilled worker production in competitive jurisdictions (late medieval Europe). In the Roman case, silver production collapsed after the mining slaves died en masse during the Antonine (165-180) pandemic and shafts got flooded. In late medieval case, as the more easily reached and smelted silver ore was mined out, new technologies were developed and silver production boomed.

Silver has been much more commonly used as a monetary metal than gold. Athens, Rome, China, imperial Spain, all used silver systems. One of the effects of the Central European, and then American, silver production booms was to shift the gold/silver ratio in Europe—according to Munro, from about 10:1 in 1400 to about 16:1 in 1650.

The late C2nd onwards collapse of Roman silver production caused the Eurasian-wide Crisis of the C3rd—which, ironically, reached Rome last—by crashing the Han-Rome Eurasian trade system. Centuries later, the flood of American silver made it very hard to sell European goods to China, as European goods were silver-expensive and Chinese goods were silver-cheap, so silver flooded into China, where it bought a lot more.

I have even seen major economic historians—I am looking at you Douglass North—write nonsense about Chinese cultural resistance to foreign goods. There may have been some, but the key thing was that European goods were expensive, for absolutely obvious supply-and-demand reasons that Adam Smith commented on.

Prosperity surges

Just as there are immiseration cycles, so there are also mass-prosperity periods. These are what some scholars refer to as economic efflorescences and David Hackett Fisher refers to as periods of equilibrium: by which he means socio-economic equilibrium. He identifies the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the Victorian era as such periods of equilibrium.

The Renaissance represents institutional and technological innovation interacting with a sudden surge in Europe’s ability to trade with the rest of the globe. The Enlightenment represents another period of institutional and technological innovation with a further increase in trade, particularly within Europe, due to the surge in canal construction. Finally, the Victorian era represents a massive wave of institutional and technological innovation interacting with the most dramatic surge in trade up to that time, due to the development of steamships and railways.

The first two periods represent increased networked globalisation, through increased global connections but with only limited change in transport and communication technologies: it was more a case of quantity having a quality all of its own. The Victorian era represents the first period of mass globalisation, as technological change crashed transport—railways and steamships—and communication—the telegraph—costs.

The interaction between Schumpeterian growth (innovation) and Smithian growth (increased specialisation) generated increases in mass prosperity, which had a stabilising effect—until they didn’t.

One of the weaknesses of The Great Wave is that Fischer tries to use history as a weapon against policy trends he dislikes. Fischer suffers from serious misunderstanding of markets flowing from confusing food prices with inflation and demographic dynamics with markets. Hayek’s point about markets representing dispersed knowledge—and the wider point about information flows in economies—eludes Fischer. Though he does include a rather nice vignette:

There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, of a conversation between Quesnay and the Dauphin:

“What would you do if you were King?” the Dauphin asked.

“Nothing,” said Quesnay.

“Then who would govern?”

“The law,” Quesnay replied. (p.116)

Markets generate and use information, and create incentives, but remain embedded in wider constraints. Yes, changes in those constraints will be reflected in markets, but that is normally an advantage of markets. There are situations where alternative mechanisms are superior—food rationing in a besieged city, for instance, where nothing can be done to increase production and folk need to hang together in face of common danger—but such cases are unusual, especially at scale.

The notion of “free” markets is always a bit of a red herring, as it sets up some sort of perfectionist standard that is never reached. Alternatively, the depiction of such markets as some unstoppable social juggernaut that needs to be tamed typically involves unwarranted confidence in alternatives that are reliably worse at generating and using information and incentives. Markets can be corrosive of social connections, but the socially-imperial administrative state is even more so. Especially if it corrodes or supplants various intermediary institutions.

Moreover, it was precisely markets and commerce that enabled massive increases in population and increases in living standards at the same time from the 1830s onwards. The created far more human niches that were also larger niches for humans (aka mass prosperity or the Great Enrichment).

Fischer writes approvingly of wage and price controls. It is perfectly true, they can suppress inflationary pressures, if they are relatively short in operation. Especially if they are part of some shared group purpose (e.g. war, siege). They are, however, a clumsy and expensive way of changing inflationary expectations. Fischer is very much against using recession-generating interest rate rises because, well, they are a clumsy and expensive way of changing inflationary expectations.

The great achievement of the Great Moderation was that central bankers became much better at anchoring people’s people’s inflationary expectations. Unfortunately, with few exceptions—most spectacularly, the Reserve Bank of Australia—they have been less successful at anchoring expectations about total spending, and thus income stability. Hence, the Great Recession—when income expectations (and so spending) crashed—which Australia avoided.

Too little distinguishing

In The Great Wave’s last Appendix, Appendix O Economics and History, Fischer makes it clear that what he calls his problem-centred approach is a revolt against Theory. I have a lot of sympathy for such a revolt. An awful lot of academic Theory is, indeed, bunk. The use of Theory to filter evidence is a curse across swathes of academe.

While some of Fischer’s Appendices are, to be polite, of variable quality, his discussion in Appendix J Returns to Labor: Real Wages and Living Standards is very sensible while that in Appendix L Price Revolutions and Inequality is informative and thoughtful

The problem with Fischer’s overall approach is not too little Theory, it is—ironically for an historian—too little thinking through the differences between phenomena. He failed to think through what transactions mean in a monetised economy. He failed to distinguish between immiseration cycles—the pressure of population on resources—and inflationary patterns—shifts in the relative scarcity of money and output. This made his work much less insightful or useful than it might have been.

None of my above critical commentary on The Great Wave rests on some elaborate Theory. It does rest on seeking to carefully distinguish between phenomena while developing an empirically-grounded understanding of their interactions.

Whatever his analytical failings, Fischer does assemble considerable data about economic and social history. He also provides a useful—and increasingly urgent—corrective against confidence in upward projections of historical progress.

ADDENDA: See also the discussion here. A nice example of getting closer to truth through dialogue. See even more so this post:

References

Philippe Aghion, Ufuk Akcigit, and Peter Howitt, ‘The Schumpeterian Growth Paradigm,’ Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 7:557-575 (August 2015). https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115412

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

Jack A. Goldstone, ‘Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the “Rise of the West” and the Industrial Revolution,’ Journal of World History, 2002, Vol. 13, No. 2, 323-389. http://culturahistorica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/goldstone-efflorescences.pdf

F. A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society,’ American Economic Review, Sep. 1945, XXXV, No. 4, 519-30. https://www.econlib.org/library/Essays/hykKnw.html

Morgan Kelly, ‘The Dynamics of Smithian Growth,’ Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, no. 3 (August, 1997), 939-964. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ucn/oapubs/10197-521.html

Tjalling C. Koopmans, ‘Measurement Without Theory,’ The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Aug., 1947), pp. 161-172. https://fairmodel.econ.yale.edu/ec439/koop1.pdf

John H. Munro, ‘Review of Fischer, David Hackett, The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History,’ EH.Net, H-Net Reviews, February, 1999. http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=2828

I am ignoring, as one should, Marx using capital in a weird way. The perennial left-progressive habit of using your language but not your dictionary—pretending to use a common term but then giving it a special meaning, to use when convenient—starts with Hegel, but Marx expanded the practice, which has continued to multiply. It is, at best, an exercise in manipulation and, at worst, an intellectual swindle.

Whether particular mass killings via hunger were deliberate on the part of various Marxist regimes is still debated. Regardless of how intentional the level of death was, terror was used to force collectivisation and to extract food for the purposes of the various regimes, including industrialisation.

That the West adopted from China bureaucratic selection by competitive examination without considering Chinese historical patterns of decay in bureaucratic government is proving to be unfortunate. Yes, meritocratic selection does lead to more effective government bureaucracies, leading to more capable states. As, however, the pathologies of bureaucracy multiply, much more toxic patterns begin to manifest, undermining state capacity and increasing popular alienation. That left-progressivism has become the politics of the professional-managerial class is both symptom and disease.

Increased bureaucratised parasitism and post-1970 mass globalisation distributing productivity gains away from Western workers, along with women entering the workforce increasing the labour supply relative to land and capital, are also factors.

I spent two hours last evening watching some young guys explore abandoned hotels and luxury villas in China, all built in the last decade and some never occupied at all. The scale of these capital "investments" is beyond belief. Economic theory has nothing to say to me at all.

How do business cycles relate to inflation cycles and immiseration cycles?