Stirrups, a rant

Stirrups did not create shock cavalry.

So, I was listening to Erik Prince talk about warfare and he came out with some stirrup nonsense.

It’s like when Genghis Khan put stirrups on horses and it enabled, instead of walking into battle, now you're galloping at the speed of a horse while standing up in the saddle firing arrows rapidly, what happened created an Empire from the Pacific Ocean all the way to Hungary.

Almost everything is wrong with this statement. Stirrups—hard stirrups on each side of the horse—predate Genghis Khan (1162-1227) by around eight centuries; horse archers did not stand up in the saddle to shoot; recurve bows able to shoot from horseback predated Genghis by around two millennia and enabled the Scythians to create the first significant steppe empire around the C9th BC.

Stirrup nonsense is endemic, as is nicely discussed here. Lynn White Jr. in his book Medieval Technology and Social Change (1962) famously (or infamously) claimed that stirrups made feudalism possible. As the warrior-franchise (“feudal”) system—a mounted warrior directly extracting surplus from local peasant farmers—first arose on the Iranian plateau over a thousand years earlier, clearly not.

Even eminent medieval historian Maurice Keen, in his 1984 book Chivalry, claimed that:

Without the stirrup, the shock charge with couched lance could not have been a possible maneuver, but the spear and saddle were also important. P.23.

Nevertheless, it was still disappointing to see a scholarly book published in 2004 repeating one of the most egregious pieces of nonsense in military history. Nonsense that I had hoped was dead and buried:

By the eighth century a new mode of warfare had emerged (the mounted shock cavalry), which in turn played an important part in creating the institutional structure of both the feudal state and economy. This was dependent on the invention of the stirrup. Before the stirrup, horses were ineffectual in battle because the rider had nothing with which to hold him securely to the horse. Accordingly, a spear could only be delivered through the strength of the rider himself. But the stirrup enabled the rider to deliver a blow with the full strength of the horse. In this way, frail human-muscle power was replaced with superior animal power, enabling shock cavalry simply to plough like a bus through foot soldiers (p.103, emphasis added).

Or, in an intriguing online economic history of the world:

The Greeks and Romans also did not use stirrups which allowed cavalry with lances to be used as shock troops in warfare. In antiquity war was mainly conducted on foot, or horses pulled chariots (Chapter 9, p.1).

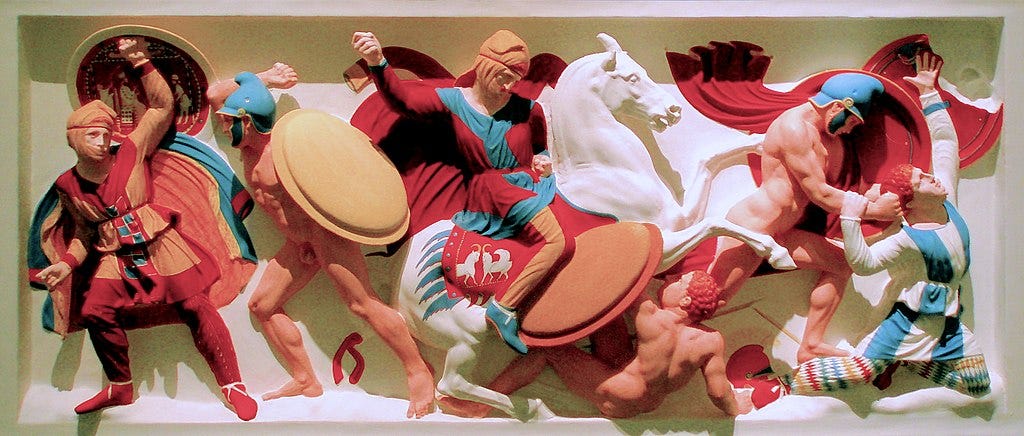

That horses were ineffectual in battle without stirrups, or were incapable of being shock cavalry, would have been news to the Assyrians, Alexander the Great—who won every single one of his set-piece battles leading his heavy shock cavalry—Hannibal, the Sarmatians, Parthians, Palmyrans and Sassanids, all of whom used stirrup-less shock cavalry. Mobility and height were sufficient advantages in themselves.

Horses had been domesticated long before the Scythians. Horses, along with dogs and reindeer, are the only animals domesticated by foragers, rather than farmers. The first significant use of horses in battle was to draw chariots. Chariot archers could shoot, and javelins could be thrown, further from a chariot than a horse.

The classic chariot was driver and archer or spearmen. A friend describes them as being like a pilot and a navigator (or bomb-aimer) on a bombing run. The pilot/charioteer concentrates on getting the pair of you where you need to be (or not to be). The archer/spearmen/navigator/bomb-aimer concentrates on killing the enemy.

The most famous driver/warrior pairing in myth and literature is Krishna and Prince Arjuna in the Mahabharata and, specifically, the Bhagavad Gita. (Normally, the driver serves the warrior, but if your driver is an incarnation of Vishnu, things work differently.) The warriors of the Iliad are also chariot-driving warriors—hence scenes such as Achilles dragging Hector’s dead body behind his chariot. Chariots were a major element in Chinese warfare up to the Warring States period. New Kingdom Egypt was very much a chariot empire, as were their great rivals, the Hittites.

Once recurve bows able to match chariot archery from horseback arrived, chariots largely disappeared from combat in the major Eurasian civilisations. This began to occur around the time of the Assyrians—who were a transitional case using both chariots and cavalry—about a thousand years before the invention of the stirrup and even longer before the stirrup’s arrival in the Mediterranean world. Lancers—the heavily armoured version of which was the cataphract—then developed as a way of dealing with horse archers.

Mobility and height were what gave the shock cavalry sufficient advantages to be effective prior to stirrups. The effect of the mass of horse and rider was a more complicated matter. As the discussion of practical trials of charging with a lance says:

In reality the rider’s body acts as a shock absorber, or buffer, between the lance and horse. It cannot be stressed enough that the rider’s own strength and weight are the key to translating the mass of the horse into the force of impact. Although the size of the medieval warhorse gradually increased over time, the effective size of the lance and horse interface (the rider) did not.

Stirrups certainly made such cavalry sufficiently more effective to see their use spread and become near universal. The aforementioned recent recreations of tilting clarify how much: stirrups did require less training; made travel and bracing easier; and were more effective in melees (hand-to-hand fighting). As the follow-up discussion says, stirrups:

makes virtually anything you can do on a horse easier to do by giving the rider more stability.

Stirrups were, however, clearly not needed for shock cavalry to be worth having. Indeed, that shock cavalry already existed is important in why the stirrup spread in the way it did, as the type of soldier and trained horses did not have to be created from scratch.

Moreover, stirrups mainly made shock cavalry more effective against other cavalry or chasing fleeing foot after the lance is broken or otherwise discarded. That horses will not charge home against steady foot that stood its ground was as true in 400BC as it was in the Anglo-Scottish wars or at Waterloo in 1815. (What horse-and-musket era infantry squares primarily did was get rid of vulnerable flanks and rears.)

Horses are pretty pliable, but they aren’t that stupid. The hollow lances of the Polish Winged Hussars gave them extra reach, which helps account for their astonishing effectiveness. The trick for steady infantry was to produce foot that was sufficiently resilient (i.e. that believed their mates would also stand).

For Lord of the Rings fans, the charge of Rohirrim at Helm's Deep gets around the “horses won’t impale themselves on steady foot” problem by having Gandalf light-shock the orcs at the crucial moment. The charge of the Rohirrim against the orc foot besieging Minas Tirith seems to assume the orcs break at the crucial moment, the sort of thing that did happen. It was scary to see a solid line of men and horses coming straight at you with murderous intent. The trick was not standing yourself, it was believing the guys around would stand: if you did not believe that, and broke, you were cactus. The cavalry would ride you down.

Stirrup nonsense sadly gets repeated a lot, but even cursory knowledge of military history indicates that it is nonsense.

But, and this is what really gets me, even cursory knowledge is not apparently sufficiently prevalent. Scholarly folk—including full-grown Professors—read cavalry ineffectual before stirrups but apparently don’t stop to ask hmmm, were there shock cavalry before stirrups? Even if you had never heard of the Assyrians (what, no Bible reading?), Parthians, Sassanids or Palmyrans, surely Alexander the Great and Hannibal should be within one’s (Western) historical consciousness.

Will this nonsense never die? How much evidence is enough?

"Before the stirrup, horses were ineffectual in battle because the rider had nothing with which to hold him securely to the horse."

Didn't seem to be a problem for the Comanche, who developed into the most horse-dependent and capable tribe after the Spanish introduction of horses.

.. and here, I thought this was going to be about gynecology.