The Latin Americanisation of the United States

Migrants make places more like where they come from.

In his excellent review of the growing literature on the deep causes of long-term economic growth, and the implications for migration—The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left—economist Garett Jones describes the Spaghetti Effect: the way migrants make the place they come to more like where they left.

Lots of Italians turn up, and folk begin to eat spaghetti. This is a relatively benign example.

There are much less benign examples. For example, Britain imports lots of migrants from countries with higher homicide and crime rates, and its crime rates have become higher than they would otherwise be, even though violent crime has declined overall. In the US, the decline is more equivocal, given that the marked increase in the efficacy of emergency care has reduced the rate of death from assaults.

As culture is persistent, migrants push institutions in the direction of their cultural patterns, their cultural schemas (modes of thought) and scripts (modes of action). For institutions are not “magical”, they operate according to the patterns of behaviour of the people in them and interacting with them.

Yes, institutions have inbuilt incentives, but those incentives are themselves based on cultural schemas and scripts. Hence, the “same” institutions can operate quite differently in different societies, a point I have made elsewhere.

Clearly, any particular Spaghetti Effect will depend on how much of a critical mass a specific group of migrants are within the new society. The larger the group, the stronger the effect they are likely to have.

Latin Americans accounted for half the US population growth from 2010 to 2020. They now constitute 62m people out of a total US population of 334m, or 19 per cent of the population: a very substantial proportion.

What would the Spaghetti Effect tell us to expect from this? That the politics—indeed the political economy—of the US would converge more to the patterns of Latin America.

Latin America and the Iberian heritage

While there is significant variation within Latin America—Costa Rica tends to be relatively functional middle class society; Argentina is overwhelmingly European in its demographics and was one of the richest countries in the world c.1900; Mexico has been very constitutionally stable for over a century—there are some common institutional patterns across Latin America.

Latin American societies tend to be highly stratified, with very high homicide rates as there are various localities that the state does little to police. The populations are generally a mixture of local indigenous populations, an African slave diaspora and Iberian settlers, with a lot of mixed continental-origin (“race”) folk. Nevertheless, the racial mix tends to be something of a socio-economic layer cake, with “white” on top and “black” and “brown” grading downwards.

Latin American states are often poor at defining and administering property rights—and often do not bother even trying in poor/underclass localities. They impose high transaction costs on their societies through a lot of regulation and official discretions.

In a notorious experiment, students of Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto attempted to set up a small textile workshop. To get the required permissions took 278 days of dealing with bureaucracy.

Despite the fact that the state imposing such high frictions on transactions obviously systematically reduces commerce—and so economic activity—this is a feature not a bug. The complex regulatory structure employs a lot of officials, enables them to make money from the sale of their official discretions (i.e. corruption) and advantages the elite, who have the connections and resources to navigate—and manipulate—the system, whose costs and complexities protects them from competition from any “uppity” middle class.

These societies are often marked by elite contempt for the poor—who the elite generally find deplorable. The poor respond to the mix of neglect and contempt via the familiar mechanisms of ostentatious pleasure, informal commerce and bravado violence.

The Spanish Empire operated as an autocratic state, whose local Parliamentary tradition had long since atrophied due to floods of American silver—the Crown did not need consent for its income and used religion as a loyalty-sorting device. The Empire reserved top positions in its colonial administrations for people born in Spain. It co-opted local elites by supporting their control over their local peasantry and providing subordinate official positions for them to profit from.

This was a very different political economy than the commercial Parliamentarianism of Anglo-America. Hence, even though European settlement started around a century or more earlier in Latin America than Anglo-America, the latter have been much more successful societies, particularly economically.

And in the US …

As for Latin American patterns in the contemporary US, consider the 2016 US Presidential election. It was between the wife of a former President and a demagogue. This a very Latin American pattern.

The comparison of Trump with Hitler or Mussolini is stupid, dangerous and ridiculous. It is particularly ridiculous given that President Trump ran the most pacific US foreign policy in decades.

The caudillo politics of machismo is a somewhat less ridiculous comparison. Trump’s “glitz everywhere” aesthetic is also rather Latin American.

Fast forward to the 2024 US Presidential election, and the Democrats have anointed their Presidential nominee in a process startlingly like that of the Mexican PRI (The Institutional Revolutionary Party), bypassing the primary process. The ostentatious bonhomie of VP Harris and Gov. Walz is also rather Latin American.

California is one of the US States with the highest proportion of Hispanic residents (39 per cent). Its political economy is becoming very Latin American. The California ruling elite uses grace-and-favour regulation to benefit itself—particularly via inflated real estate prices—and a bloated, increasingly dysfunctional, public sector, while squeezing out the middle class, who are moving to other US States.

California is becoming more Latin American not only in its political economy, but in driving folk to become economic migrants, fleeing to the US.

Texas also has 39 per cent Hispanic residents, but it does not seem to have become anywhere near as Latin American in its political economy as has California. This despite oil providing an excellent basis for such a political economy. The answer may be as simple as the Red State model resists Latin Americanisation more than the Blue State model does. How successfully, and for how long, we shall see.

Expect it to continue

Given that Latin American states are much less functional than is the US—and have a long, long history of being so—the Latin Americanisation of the political economy of the US would seem like something to avoid. But to actively do such would require celebration of the Anglo-heritage that set the US on a very different institutional path to Latin America. This is something that much of the US intellectual elite has become overwhelmingly hostile to doing. (Though, again, rather less so in Red States.)

Moreover, if you are the incumbent US elite, creating a crony capitalist structure where grace-and-favour regulation squeezes out an unruly middle class and enables successful repression of one’s working class may seem like a great idea. It may seem so even if it means that US state capacity continues to decline.

(For those who think the US is a well-governed country by developed world standards—it is not—I have one word for you: Detroit.) An ever-expanding administrative state using “wokery” as a moral-project-generating loyalty-signals also has Latin American resonances.

To stop the continuing Latin Americanisation of US political economy would—at the very least—require folk to notice it, to notice the causes, and to publicly discuss the same. There is a whole lot of pressure against that.

There are too many vested interests—and too many intellectuals-yet-idiots—who would be very, very vocally against doing any of the above. Ranging from adherents of social alchemy Theory who actively want increased social dysfunction; to liberal-progressive NPCs who parrot—indeed shriek—“racism!”, “xenophobia!” etc., at any suggestion that culture might causally matter; to open border-libertarians who are as much blank-slate folk as their progressive opponents, treating migrants as utility-maximising interchangeable widgets who will follow, and replicate, the existing incentives due to the power of the “magic dirt” of the United States.

None of these folk are much good at noticing inconvenient realities where it contradicts their Theory. On the contrary, they use their Theory to grade, select and frame evidence.

So, the Latin Americanisation of the US will continue. US political economy will continue to drift towards the patterns of Latin America and away from those of the Anglosphere. This has not been, and will not be, an improvement.

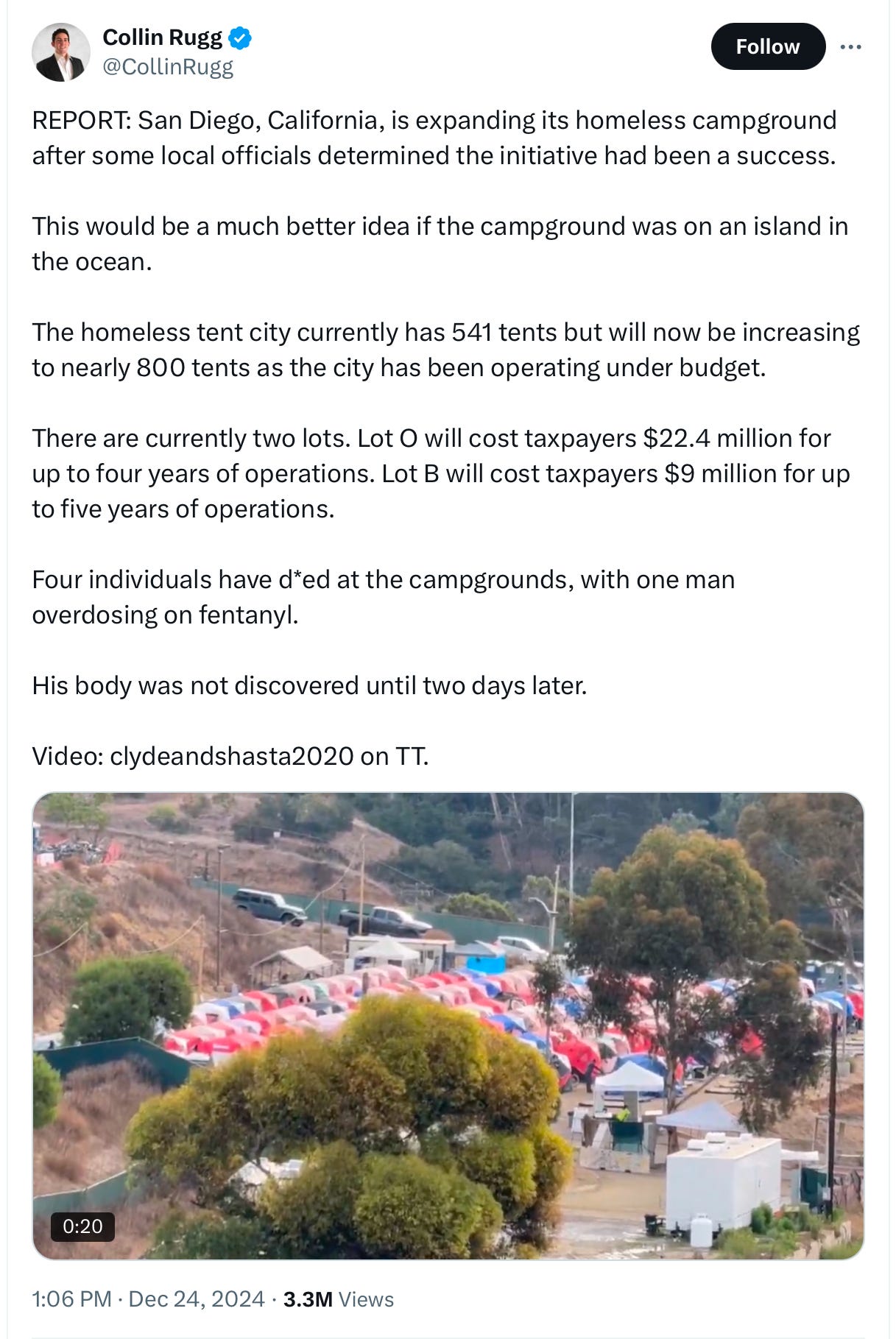

ADDENDA: The beginning of creating, in California, a shanty town, a favela.

ADDENDA SECUNDUS: Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Although using very different methodologies, the studies all provide evidence leading to the same general conclusion: individuals from different cultural backgrounds make systematically different choices even when faced with the same decision in the same environment. (Emphasis added.)

References

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano, ‘Culture and Institutions,’ Journal of Economic Literature, 2015, 53(4), 898–944.

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353.

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Robert Neuwirth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

I live in California and have been to Brazil many times and I think it's hard to deny that California is deep into its process of Brazilification, there will be no going back, and by the middle of this century it will fulfill its destiny and become a newer, richer, much more powerful Brazil.

The similarities are striking: a paler-skinned elite class with massive wealth hogging all land and assets, living in distant estates behind tall gates (we don't have armed guards here yet, but will soon); a vast darker-skinned peasantry who will never afford land of their own and who live either on low-wage dead-end jobs or govt handouts; an impervious corrupt political class who somehow make millions while being employed as "public servants"; and while Brazil still has priests to tend to the needs of the poor, our priests are called Professors of Social Justice, but the process is the same, applying metaphysical balm to psychic wounds on behalf of their oligarchic employers.

The same is true throughout the West. Our ownership class decided it could no longer afford the bottom half of its citizenry—too many demands, too many expectations, always wanting their cut of the national loot, too much power to vote them out of office—so it's decided to immiserate and silence them and import their (much more docile and easier bought off) replacement.

Twenty-first century California is somehow both our first postnational state and a feudal aristocracy at the same time.

Based on the comments thus far it seems that you’ve poked a sore spot. To do that, of course, you have to hit some bullseyes, and you have. I, too, am a Cali native and can attest to it, though there are some confounding circumstances and realities that you may have missed from down under. For one, California, having only reached full industrialization with the advent of WWII, is an imperfect example of American malaise. And the flight of the white middle class, which is widely noted, is hardly a flood of refugees in the face of an advancing horde. It has been entirely facilitated by the irrepressible growth of real estate values. If your worn-out ‘60s tract home can be rebranded as a mid-century modern diamond in the rough, why not sell for 50-100x the original purchase price and move to…AZ, TX, or wherever? That solves all your nagging retirement income probs in one fell swoop! And, in fact, much of what has propelled that development over the last 15 years is money from Asia. Though the percentage of the population that is Hispanic is high, arrivals from China, Korea, Vietnam, etc. have been substantial in recent years and rivaled immigration from Latin America in sheer numbers. Vancouver BC has apparently experienced much the same influx since the late 90s from Hong Kong in particular. In fact, Cali has been a diverse society from early on, and the get-rich-or-die-trying mentality can trace its roots directly to the gold rush era - a period when the more established were also overwhelmed by incomers. An aspect of Hispanic immigration that is not well noted in its nuances is the odd phenomenon of politically right-leaning small business owners declaring their distaste for unfettered immigration while welcoming with open arms the effect of it on the lower end of the wage scale. I’ve seen that first hand, and it’s a major impediment to any pity I might otherwise feel for said proprietors. Also, Cali has attracted enormous investment of government dollars, particularly since WWII, even as it has repaid much of it with tax revenue and entrepreneurialism. It’s a messy, complicated picture made only more so by a full weighing of its modern history. Perhaps no one individual symbolizes it as fully as Earl Warren, the governor who pushed Japanese internment being one and the same as the Chief Justice who brought forth the Brown decision. Is the state on its way to Brazilification? Time will tell. But there are always elements in the complex picture that may prove critical even as they are overlooked.