Breadwinners, homemakers and the decline of patriarchy

Fathers as providers has been the human norm.

In researching the social patterns of male-female interactions, Dr Alice Evans has done field work around the globe, and immerses herself in the evidence. She provides highly intelligent analysis of male and female dynamics across human societies. See, for example, her Unified Theory of Marriage. Nevertheless, I found this recent post niggling at me: its analysis seemed to be missing something.

In particular, the implication that patriarchy increased in the C19th compared to the C18th seems clearly wrong. The C19th saw the beginnings of the unravelling of the legal props to patriarchy, including the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act and increasing agitation for, and in some places achievement of, female suffrage.

The problem, as is so often the case in social science, but particularly social science with any sort of feminist tinge, is failing to grapple with the reality that the social is emergent from the biological. To this is combined another frequent analytical sin: not having a broad enough consideration of historical patterns.

Risks and resources

Humans have very biologically expensive children. Our infants are remarkably helpless. In foraging populations, it can take almost 20 years for a human child to be able to forage as many calories as they consume. Prior to the invention of farming, a mere 11,000 years ago, having Homo sapien babies was a rolling, almost 20-year, project.1

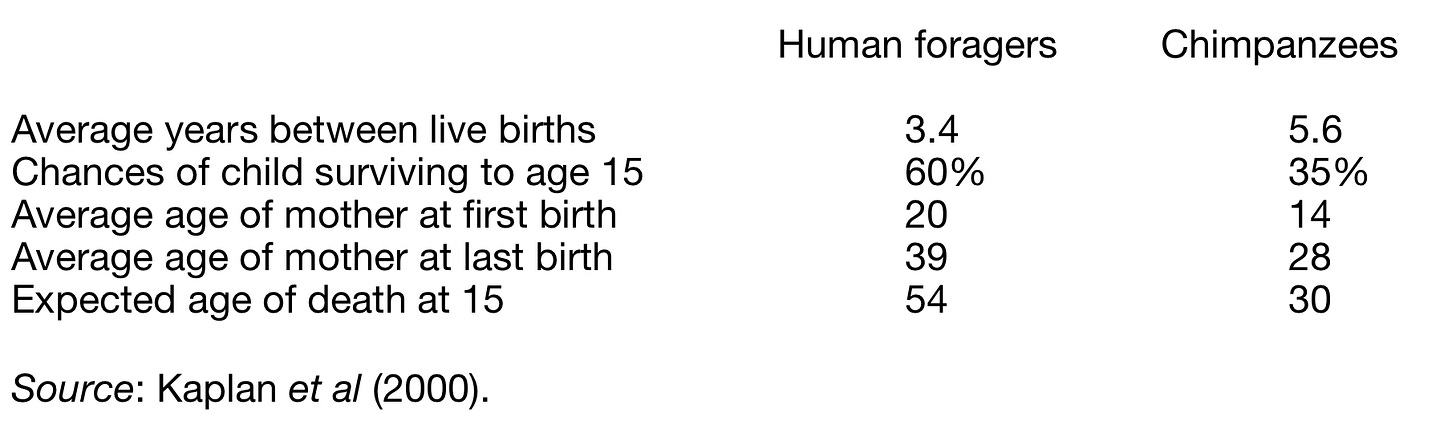

Comparisons between ten cultures of human foragers and five communities of chimpanzees, our genetically closest relatives, shows some striking differences.

Despite human children being much more biologically expensive, forager mothers have more children, their children have a much higher rate of survival and they are much more likely to still be alive when their last child is a juvenile.

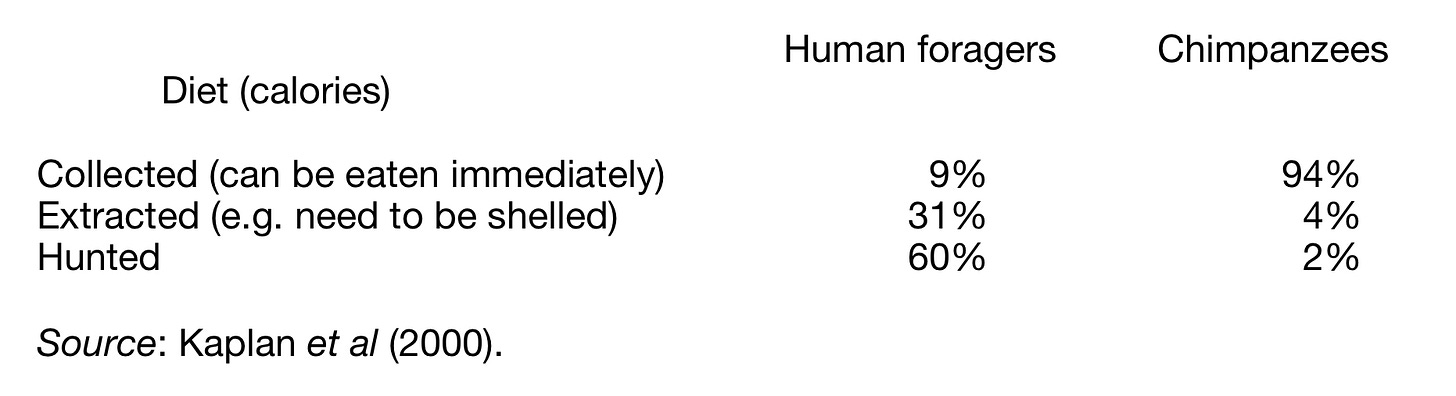

These differences go with very different calorie profiles from very different subsistence strategies.

Chimpanzees spend about half their waking hours chewing food they have grabbed. Human subsistence requires significantly higher skill levels. This is why it takes so long for forager children to reach subsistence adulthood.

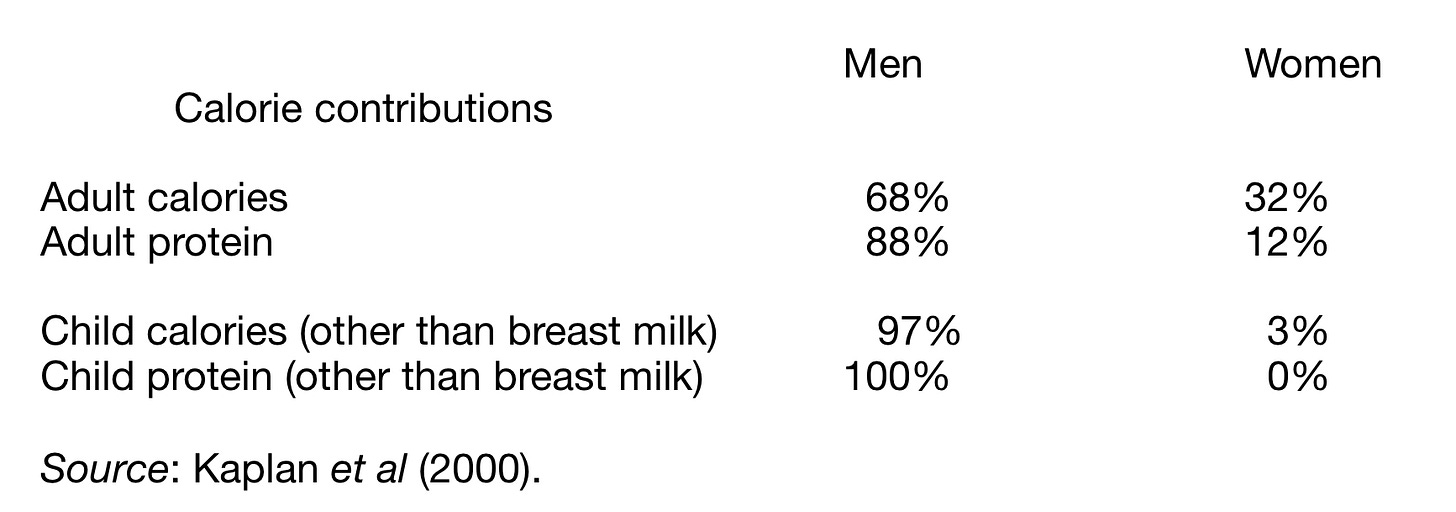

The most dramatic difference comes from who collects the calories.

Chimpanzees are not included in the above because the sexes operate independently. Chimpanzees do share food, but strategically as part of coalition strategies, not habitually in the group.

Human subsistence strategies are cooperative because our reproduction strategies are cooperative. That is how we can successfully raise our biologically expensive children. The fundamental pattern of human societies is to transfer risks away from child-rearing and resources to child-rearing.

In most mammal species, the males have nothing to do with raising the children. The mammary glands of the females mean they are already committed to feeding their offspring.

Among mammals, Homo sapien males are wild outliers when it comes to providing resources for their offspring. Indeed, Homo sapien males are such outliers that it is standard, in foraging bands, for unmarried males to provide food for other people’s offspring. That establishes their own suitability as mates while allowing them to, in effect, trade food across time. The sharing of food in the foraging band means they are covered when they fail to find food or are injured or sick.

Human fathers as providers is not some invention of the Industrial Revolution. The fundamental evolutionary reason to create the social relationship of fatherhood2 via marriage is to provide resources for, and cover risks of, child-rearing for our very biologically-expensive children.

We being the cultural species, so remarkably flexible, the degree and ways fathers operate as providers has varied hugely across human societies. Indeed, the role of fatherhood varies much more across human societies than does motherhood. This is hardly surprising, as motherhood is much more biologically grounded while fatherhood is much more culturally created. (And therefore, as we are discovering, more culturally vulnerable.)

Nevertheless, the pattern of father-as-provider is deeply embedded in human society and evolution and has been for thousands of generations: so across evolutionary time.

This needn’t only be a matter of providing subsistence. Family or kin identity, protection, connections: these can all be part of paternal provision, broadly understood, operating via marriage creating the social relationship of father. The one feature common to all marriage systems (apart from creating the social role of father) is that they create in-laws, kin-connections, spreading out from each marriage.

It is very common in marriage systems for the groom to have to demonstrate in some way their capacity to be a provider, such as paying a bride price. The bride was often not the person to whom such a demonstration of ability to provide was directed: rather, it was often directed to the bride’s parents or other kin.

Homo sapiens are the only species where mates have frequently not chosen each other, but rather are chosen by their parents or other kin. Courtship marriage is relatively unusual in human cultures: it is very unusual across human societies for it to be the dominant form of marriage. A survey of the anthropological data found that in only eight out of 190 foraging cultures was courtship marriage the dominant form of marriage. It was significant, subject to parental approval, in another 15.

Homo sapien males have evolved, both genetically and culturally, to be providers. It is surely hardly surprising that there are deeply embedded cognitive and cultural mechanisms that psychically reward men for being providers and punish them for failing to be so.

Out of households

To see factory work as creating some new expectation of father-as-provider is to profoundly mistake what was genuinely new about the Industrial Revolution. What the factories of the Industrial Revolution did is replace the productive role of households. Households stopped being the most common unit of production while retaining their role as the primary places of consumption.

In a peasant society, a household can only consume what it produces or trades its production for. The household itself is a productive unit. This has been the dominant pattern for human households since households first evolved in sedentary foraging societies. For instance, the Jāti system (the key element in the Indian caste system) seems to have originated as a mechanism for maximising Brahmin household production, spreading from there across occupations and acquiring other risk-management roles as it evolved.

People shifting from being peasants to factory workers moved production outside the household and meant that work became cooperative, with payment almost entirely monetised and standardised. Men worked together and then socialised afterwards.

Work became also much more public than it had been. Neighbourhood connections weakened somewhat but wider connections became much more common. This combination of shared experience and wider networking is why agitation for adult male suffrage was so much stronger in the C19th than it had been before.

The effect of the growth of factory work was to greatly strengthen working-class fatherhood. Something that has become ever more starkly obvious as the collapse in factory employment, wage stagnation, and the loss of male income advantage, have undermined working-class fatherhood, with a range of deleterious consequences.

When feminism treats motherhood as an career/income inconvenience, it misses that motherhood is so central to parenting, that fathers have to be the net provider, or have some other equivalent status benefit they are bringing to the relationship, to balance it out. Men and women having equal income possibilities undermines the ability of men, particularly working-class men, to bring something to the marriage to balance out motherhood.

The notion that motherhood and child-rearing is somehow an incidental feature of human interactions, especially marriage, so motherhood’s most salient feature is that it gets in the way of women achieving everything men do, is bonkers. Fundamental to what makes women, women, is the biological possibility of bearing children, with all the physiological and cognitive consequences of that.

A considerable amount of the early popularity of the Covid lockdowns was precisely that women got to stay home with the kids. You can commute and get enough sleep, or you can have small children and get enough sleep, but you can’t do both and get enough sleep.

Unfortunately, a lot of commentary on the shift of production away from households engages in what has become the normal feminist belittling of men: women are so obviously a purer form of Homo sapien that if men could just get with the program and be more like women, all will be well. To which is added more than a little of the sadly normal pattern of highly-educated women belittling working-class men.

A deep irony here is the feminist insistence that women must have all the declared-good things to the same level as men turns women into ersatz-men deformed by the possibility of pregnancy. The happiness data suggests that has not been a good strategy for women.

The problem with the breadwinner/homemaker pattern is that it was unbalanced the other way. Women became more starkly dependent and, as suburbanisation spread, more socially isolated. The more housework became a matter of managing appliances, so both less time-consuming and less skilled, the more the isolation was revealed.

The advent of mass schooling — to produce good little factory-workers, office-workers and soldiers — lessened the child-minding role of motherhood. This tended to increase the isolation but also increased the time available for outside employment. The reduction in the strength demands, and particularly the risk level, of jobs increased the range of outside-the-household jobs available to women.

All of which led to agitation for female suffrage. Something that is regularly missed in the “patriarchy-as-oppression” simplicities is how short the time-gap between adult male suffrage and female suffrage was. In the UK, full adult male suffrage was not introduced until the 1918 Act that also brought in (more age-limited) female suffrage.

But, with both male and female suffrage, we are dealing with a civilisation with a long history of legally-entrenching political bargains. A civilisation, moreover whose dominant religion, Christianity, had sanctified the Roman synthesis: single-spouse marriage, law as a human creation, no consanguineous marriage, female consent for marriage, individual wills coupled with testamentary freedom, suppression of kin-groups.

On the way through, the Church added extras, such as no adoption, greatly expanded incest bars, and anathematising all sex outside marriage, including bastardy. As I discussed in a previous post, this combination provided various advantages for women, particularly married women. It led to European Christian civilisation being much less patriarchal than Islam, Brahmin civilisation or Confucian civilisation.

Whether or not a society is polygynous has a major impact on its sexual and economic dynamics.

As discussed in my previous post on patriarchy, the C19th American West provides a revealing “natural experiment” in the very different effects of a shortage of women in mainstream American society, with its single-spouse marriage and lack of kin-groups, compared to what happened in Chinese communities, a polygynous civilisation with kin-groups and kin-group substitutes.

Drowning in evolutionary novelty

We are living in an era of ever-expanding evolutionary novelty. This is generating both great opportunities and serious problems — such as the metabolic disaster that is the industrial processed-food diet.

Navigating these expanding evolutionary novelties is going to take a great deal of thoughtful action. It is going to require effective application of the evolutionary lens. Starting with fully grasping the reality that everything social is emergent out of the biological.

Alas, the irresponsible cognitive narcissism that academe is so prone to, giving themselves overblown moral and intellectual airs — including spurious expertise based on Theories that are mountain of bullshit built on molehills of truth — actively works against confronting intelligently the evolutionary novelties that beset us.

A feature of transformational politics, which academe is also so prone to, is that it does not accept the sovereignty of reality. Rather, it seeks to have reality bend to the wishes of its proponents. So there is no problem of obesity, just of fat-phobia.

A particularly egregious manifestation of such cognitive narcissism creating righteous identities claiming righteous authority is the delusional nonsense about the alleged sin of “biological essentialism” and science as “white supremacist, patriarchal, cis-heteronormative”. Such irresponsible cognitive narcissism is deeply socially corrosive, indeed deranging, and, given the level of evolutionary novelty we are swimming (or drowning) in, potentially disastrous, even catastrophic.

One consequence of the evolutionary novelties is misleading signals about the time frame involved in having children. This, along with massive shifts to apartment living, is collapsing fertility rates, with women forgoing having children more than they wish to.

Such fertility collapses are less intense where there is more single-parenthood. Alas, there is a great deal of evidence that single parenthood is not good for children and that fatherlessness in particular has a range of adverse consequences. This should be hardly surprising, as we clearly evolved to be raised within socially-embedded pair bonds.

These adverse consequences of fatherlessness are very unevenly distributed across society. The undermining and decline of working-class fatherhood is not a healthy development. Suggesting or implying that working-class men should just “get over” not being able to bring something distinctive to their marriages, when the lack of that clearly matters — for entirely understandable reasons — is both simplistic and unhelpful.

Human flourishing requires patterns that work for both sexes.

References

Kermyt G. Anderson, ‘How Well Does Paternity Confidence Match Actual Paternity? Evidence from Worldwide Nonpaternity Rates,’ Current Anthropology, June 2006, 513-520.

P. W. Anderson, ‘More is Different,’ Science, New Series, Vol. 177, No. 4047. (Aug. 4, 1972), 393-396.

Menelaos Apostolou, ‘Sexual selection under parental choice: the role of parents in the evolution of human mating,’ Evolution and Human Behavior, 28 (2007) 403–409.

Roy F. Baumeister, Is There Anything Good About Men?: How Cultures Flourish by Exploiting Men, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Joyce F. Benenson with Henry Markovits, Warriors and Worriers: the Survival of the Sexes, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Chris Bidner, Mukesh Eswaran, ‘A gender-based theory of the origin of the caste system of India,’ Journal of Development Economics, Volume 114, 2015, 142-158.

Lyanne Brouwer and Simon C. Griffith, ‘Extra‐pair paternity in birds,’ Molecular Ecology, 2019, 28, 4864–4882.

Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage, Penguin, 2005.

Harry Frankfurt, ‘On Bullshit,’ Raritan Quarterly Review, Fall 1986, Vol.6, No.2.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Erik P. Hoel, Larissa Albantakis, and Giulio Tononi, ‘Quantifying causal emergence shows that macro can beat micro,’ PNAS, December 3, 2013, vol. 110, no. 49, 19790–19795.

Hillard Kaplan, Kim Hill, Jane Lancaster, A. Magdalena Hurtado, ‘A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity,’ Evolutionary Anthropology, August 2000, Vol.9, Iss.4, 156-185.

Louise Perry, The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century, Polity Books, 2022.

Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell with Mind And Matter & Autobiographical Sketches, Cambridge University Press, [1944, 1958, 1992] 2013.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021).

Betsey Stevenson, Justin Wolfers, ‘The Paradox Of Declining Female Happiness,’ NBER Working Paper 14969, May 2009.

Farming takes less skill and involves less risks than foraging, so children are more productive earlier. That farming niches are smaller than foraging niches is, along with growing food rather than just foraging it, a major factor in the farming take-off.

As distinct from the biological relationship of paternity. Compared to other pair-bonding species (e.g. birds), human fathers have a high chance of being the biological father, ranging from 98% when paternity confidence is high to at least 70% when it is low.

I think it's never been easy to have a sensible discussion of the natural place of men and women in the scheme of things but you've made a good attempt. It mostly gets bedeviled by feminist man-bitching, sexual mind-games on the one hand and defensive male bragging /bravado mind-games on the other.

In my view that sane discussion would need to encompass a complex reality in which some women can make great leaders and chief executives but MOST women want a basically semi-patriarchal, semi-submissive relationship to their husbands. I'm not holding my breath.

@barsoom sent me

https://substack.com/notes/post/p-135753849