Conventions, conventions everywhere! (Also culture, pacification, law…)

On Acknowledged Possession (3).

Some time ago, I was intrigued by how China managed to have a massive commercial take-off well before it legalised private commercial property (in 2004). I therefore wrote a 12,000 word essay on the origins and dynamics of property. That is far too long for a Substack post, so I have broken it up into a series of posts.

The first post established that property predates the state or the law. The second post examined how property could operate outside—or even against—the law. This post looks how pervasive conventions are, the uses of law, pacification, and different institutional paths.

As discussed in the first post in this series, a convention is a bundle of congruent mutual expectations: things we do because we expect other people to do those things. Imitative behaviour, shared signals and common norms generating congruent expectations is the basis of convention.

Conventions rely on descriptive norms—should do X because others do X—and tend to be self-reinforcing by creating win-win patterns of interaction. Conventions are very useful things to have. Languages are bundles of conventions.

Economists tend to focus on transactions, especially monetised transactions. Transactions are choices, they are interactive, and—if monetised—come with their own quantifications.

Yet, transactions are, in all sorts of ways, embedded in connections. Firms exist because some things are better managed by connections than transactions. This is even more true of families and households.

If we look at how humans interact with resources, we can identify the following. Things that are accessed in common. Things that are actively shared. Things that are given. Things that are exchanged. Things that are coerced (taken or imposed). Connections feature across these modes of interaction at least as much as transactions do.

A park represents common access. A potluck feast is active sharing. Gifts are a regular feature of social interactions. Buying and selling is at the heart of all commerce. Taxes are a thing, so is theft. All these interactions with resources are also interactions with other humans.

Such interactions involve signalling (whether active or passive), conventions and norms. The conventions of mutual acknowledgement that establish property are embedded in a wider realm of signals, conventions and norms (such as language). It is the existence of that wider realm that enables us to so readily adopt and use the conventions of mutual acknowledgement that establish property.

Culture and conventions

Conventions vary across realms of action and across cultures and localities. What is unusual about the conventions of property is that they are so useful the core of them are universal (or near-universal) across human societies.

Consider the similarities and differences between operating in a public space like a park; a group space such as a school; or the family or household space of a home. None of these operate on exactly the same set of signals, conventions and norms, but they all have them. Such things are the necessary grease of human interaction. Uses of public spaces have, for example, rules of deference that will apply in particular localities while varying between cultures.

Hence it can be psychologically disturbing when such presumptions are suddenly broken, or you are confronted from a very different pattern than what you are used to. For example, a Muslim traveller (Evliya Çelebi) being gobsmacked—and later writing about this cultural weirdness—that the Emperor in Vienna habitually stopped to allow ladies (mere women) to pass in front of him (Lewis, Pp287-8). Such outlandish claims apparently led to many of his compatriots thinking him quite the liar (shades of Marco Polo).

Rules are not necessarily law. They can emerge out of repeated interactions over time. People grow up absorbing the conventions, signals, norms of their society. All of these can evolve over time. This is how high-trust societies are created—particularly in well-pacified societies.

If newcomers are relatively few—or at least are only in small numbers for any particular group—it becomes relatively easy for them to absorb and integrate into those conventions, signals, norms. The larger the numbers, the more concentrated the groups, of newcomers, the harder and less it is likely such integration is to happen. The bundles of conventions, signals, and norms that enable a high-trust society can then be lost.

There are at least two silly ways to think about cultures. One is to think of them as like accoutrements you take on and off at will. Cultures are not decorations, they are not fashion accessories. Cultures are functional.

Requiring a certain amount of assimilation from newcomers is about keeping the society at least as functional as they found it. If immigration degrades the ordinary functioning of a society—as it absolutely can—that is a cost of immigration; potentially a serious one.

Another silly way to think about culture is to treat the specific characteristics of a culture as irrelevant, as if it was just personal taste. To act as if, having identified the demographic geometry of cultures in a society—i.e., number, sizes, shares—that is the key data, so the actual characteristics of the cultures are not relevant. Indexes of ethnic fractionalisation only measure the demographic geometry of cultures in a society, so tell us much less than is often pretended.

Cultures are not interchangeable social integers. They are not formless things, full of interchangeable human widgets.

As noted in the previous post, how collectivist a culture is correlates almost linearly (0.91 correlation) with how corrupt that state is. As culture generates framings (schemas), plus patterns of actions (scripts)—and we humans cognitively model significance not facts—we cannot neatly separate culture from incentives, for people from different cultures will act differently in similar circumstances.

Consider how a local government manages public spaces. Does it build with a drab, even ugly, functionality—a form of disrespect for the users—or does it invest in a sense of beauty? The latter is much more likely to happen when there is a confidence in a cultural heritage, as cultures typically come with their own aesthetics.

Much of the point of culture is to help us cope with the burdens of self-consciousness. The mythic power of a culture is deeply bound up in such, hence being tied to an aesthetics. A large reason why the “soft power” of Hollywood had declined so much is that the mythic power of culture has been abandoned for self-righteous status games (such status games being central to “wokery”).

Private goods

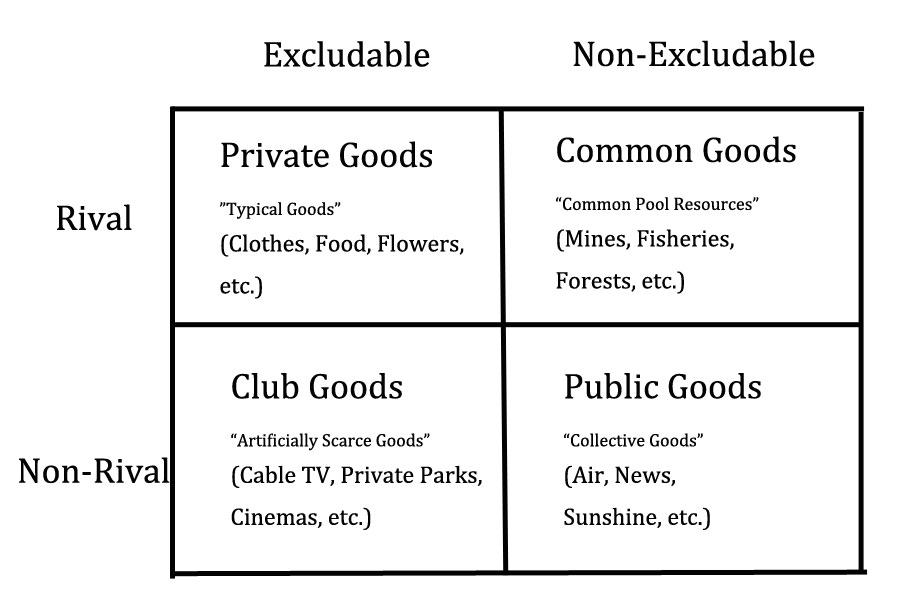

Economists grade goods by whether they are rivalrous or non-rivalrous (lots of people can consume it simultaneously) or excludable or non-exclusory (you cannot stop people consuming it). These two binary axes gives us four types of goods.

That private goods are both excludable and rivalrous makes easy to develop right-to-decide conventions by mutual acknowledgement (i.e. property). The other types of goods require more complex management mechanisms.

Given the necessary for workable rights-to-decide—i.e. rights-to-decide that are both feasible and motivating—some level of so-called “commodification” is necessary to deal with resources at scale. (The Marxian notion of “commodification” is obfusticatory metaphysical bullshit that, like the rest of Marxist Theory and its derivatives, is used to boost the status and authority—and justify control by—the proponents of said metaphysical bullshit.)

If exchanges of private goods are sufficiently embedded in connections—in networks—then fair dealing will be selected for when, due to sufficiently disseminated reputational information, breaking contracts (or other bad behaviour) means that others will no longer deal with you and the expected loss of income is greater than the gain from breaking the contract. In such a situation, as we can observe, commerce and markets can emerge regardless of legal sanction.

Market-dominant minorities emerge—especially in low-trust societies—because they are commerce-oriented and their internal networks operate as superior information, reputation and risk-management (and so trust) mechanisms. Their in-group coherence is both an advantage and a vulnerability: there is a long history of massacres and expulsions of such minorities.

About law

Where are laws most useful? When we have to deal with folk you are forced to deal with. That is, when private exclusion is not enough.

This does not mean that law will automatically improve matters. For example, the forced associations of anti-discrimination law has clearly retarded the ability to sanction bad behaviour by shunning people.

Conversely, social media, with its massively attenuated presentation of the human, has metastasised shunning of people—thereby creating cancel culture—precisely because the lack of substantive connection minimises the cost of such actions. This was aggravated by academe systematically turning beliefs into moral and cognitive assets to be defended by moral abuse, punishing and deriding dissent as illegitimate.

As discussed in the other posts in this series, law can increase transaction costs, thereby increasing transaction friction—i.e., slowing the rate which people engage in mutually-beneficial transactions. Precisely because property is based on conventions of mutual acknowledgement—so pre-law and pre-state—exchanges can then move to informal markets so as to transact more freely.

As conventions are rules, and social norms can involve sanctions, law and morality resemble each other. They are both mechanisms for generating robust shared expectations based on if-then and you-should (or should-not).

Morality and law resemble each other, but they are not the same. They do not even have any necessary or inherent connection. There is a persistent tendency to over-theorise the connection: hence various notions of natural law, or of inherent human rights (which is just natural law in secular guise, so operating theologically naked).

Law is: rules with remedies plus some method of adjudication. Law is very convenient when people are forced to deal with each other. It is a human mechanism to deal with interaction problems among people forced to deal with each other. There is no necessary moral content to its function or its purpose, though law will tend to work better when it runs with win-win conventions rather than against them.

The return on pacification

According to Dugald Stewart, in 1755 Adam Smith told his students in a lecture that:

Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things. All governments which thwart this natural course, which force things into another channel, or which endeavour to arrest the progress of society at a particular point, are unnatural, and to support themselves are obliged to be oppressive and tyrannical.

We are back to the paradox that a state powerful enough to protect is also powerful enough to predate. Indeed, it can, and usually does, do both at once. The question is, how much of each does it do, how, and how well or badly?

The more powerful the state, the more it can predate. The larger the state, the easier it is to hide predation. One wants a state that is both sufficiently capable and accountable: a difficult double.

The expansion of commerce in the People’s Republic of China after 1978 points to a much larger pattern across human history. How—ever since the emergence of chiefdoms and states (mostly) brought to an end the harrowing of male lineages known as the Neolithic y-chromosome bottleneck—the social return from pacification has generally been greater than that from commercialisation. Indeed, to achieve high levels of commercialisation has required such pacification.

Conversely, commercialisation dominates the prospects for sustained economic growth, with command economies only being able to generate significant output growth by adding inputs. Such growth mainly came from shifting peasants to factories and using them in productive techniques that were themselves the results of commercial discovery in mercantile societies.

Across history, states have existed on a spectrum from the autocratic to associational. That is, states dominated by a ruler to states where various forms of formal bargaining are central to their politics.

For most of human history, autocratic—which is to say predatory—pacification has had the advantage over bargaining or associational pacification by being much more able to scale up. An autocrat could rule a far larger area and population than a citizen or warrior assembly could incorporate. This limitation on the scale of bargaining/associational pacification was not able to overcome until the development of the representative principle in medieval Europe.

Revealingly, the representative principle came out of the wish of medieval rulers to bargain with merchants and knights. While Frederick Barbarossa (r.1155-1190) failed to make such representativeness work as he wished at the Diet of Roncaglia (1154,1158), Alfonso IX of Leon and Galicia (r.1188-1230) was much more successful in his efforts to increase taxation through formal bargaining. Efforts that were later replicated by Simon de Montfort and then taken on by Edward I Longshanks (r.1272-1307), which enabled him to avoid the problems that had plagued his father, Henry III (r.1216-1272). Parliamentary states with significant mercantile interests persistently bargained for higher taxes in exchange for more effective provision of public goods.

States provide protection against predation by other states. Enforced law provides mediation services and protection against private predation, and even—far more so in associational states—against at least some internal state predation. All of such protections can provide large social benefits. While kin-groups, and other non-state mechanisms, can provide mediation and protection against private predation, even they work far better within the ambit of state pacification.

Ironically, corruption can provide protection against aspects of state predation by buying acquiescence from state officials. Indeed, that is the reason for a significant amount of such corruption. Conversely, corruption can also allow private actors to benefit from state predation: crony capitalism being the obvious example of such.

Nevertheless, the social return from pacification is so large, states with weak or absent rule of law can still support considerable commercial activity. Indeed, the revenue advantages of such commercialisation can lead to self-denying restrictions on state predation. The grants of charters to self-governing cities by medieval rulers is an example of such. So was the evolution of successfully Parliamentary states.

Manageable transaction costs

Economic agents can and do use connections with others to reduce uncertainty and manage risks, further strengthening the conventions that generate mutually-acknowledged possession. This provides a wide range of possibilities that, without achieving the level of uncertainty reduction—and so risk clarification—that efficient property-rights regimes generate, can nevertheless enable considerable commercial activity.

As noted above, if the state does nothing more than block public violence, it thereby creates a common social space within which such passive acquiescence in acknowledging possession will be naturally ubiquitous. That alone is a powerful protector of functional property rights, even if the state does not formally ratify property rights or does not provide adjudication services—whether at all, or sufficient to cover the demand for such. (The only bit of Magna Carta that wanted greater royal authority was for more regular circuits by royal judges.)

Many societies have had private providers of adjudication services covering property disputes. Folk have been willing to use such services for the same reason that they acquiesce in the possessing(s) of others: it eases their social interactions.

By using such adjudication services—and abiding by their decisions—folk establish their reliability as social and commercial interlocutors. More generally, the broader the ambit of one’s repeated trading activity, the more value there is in a reputation for fair dealing; which includes respect for shared mediation services. This becomes a natural extension of the conventions of mutual acknowledgment that create property.

The value of Sharia, and Sharia courts, in providing a shared system of commercial law and adjudication, had much to do with the spread of Islam along trade routes, particularly to Indian Ocean islands and Malay-speaking islands and peninsula. Sharia had an advantage from significant borrowing from Roman commercial law. More recently, the provision of such adjudication services also had much to do with how the Taliban was able to maintain networks of support within rural Afghanistan, leading to its recapture of the country.

One sign of how effective is the suppression of violence, is how much effort violators of the conventions of presumptive possession put in to hide or obscure their violations. Hence, what makes a riot, a riot, is the breakdown of the presumptive hiding of violence. Just as what makes looting, looting, is the breakdown of presumptive acknowledgement of possessing by others. Though, at some point, looters (like all thieves) will want a return to the presumption of possession so they can more securely benefit from their gains.

The last is a revealing manifestation of how much the violation of the presumptive possession by others is itself parasitic on the conventions of property. They steal to possess.

Conventions of acknowledged possession both aid, and build on, the role of connections between people. The atomised individual may be more willing to violate such presumptions but is also a more likely target of such violations.

The use of (typically kin) connections to provide protection-via-retaliation—which is a method for protecting life, person and property particularly common in horticultural and pastoralist societies—can set off cycles of feuding. One of the ways that states pacify is by breaking such patterns of retaliatory feuding. Yet that can still leave kin-groups providing many useful asset and risk management benefits to members.

Societies with strong kin-groups often use private adjudication services quite extensively, as protection of one’s standing within the kin group helps motivate use of, and abiding by, such adjudication. Imperial China actively encouraged such a role for kin-groups, as it enabled significant economising on administrative costs by the Imperial state.

Given the sheer scale of China, there were limits to how large an administrative structure—built entirely around command-and-control—an Emperor could hope to retain control of. Hence imperial law came to promote the authority of kin-groups so as to economise on administrative effort. Rural China developed mechanisms—based on connections, networks and strong senses of proper behaviour, including patterns of deference—to avoid becoming entangled with the courts.

Certain connections may also protect one’s violation of the presumptive possession of others. Hence the tendency of criminal gangs to form so as to protect, organise and enable such violations (and possession of the assets gained therefrom).

Such gangs are also a very useful protective device when engaged in black market activity and may be necessary if operation within the black market involves significant issues of scale or complexity in provision. Similar reasons generate corruption networks: the wish to retain credibility within a network, including being mutually compromised, encourages being a more reliable corruption partner (i.e., that one stays “bought”).

Every bit as much as other firms do, criminal gangs wrestle with choices of whether to transact externally through trading in markets (or, being criminal, via taking) or internally through organisation: which is to say, by managed connection, using structured sharing of resources. Such boundary choices that depend, as with other firms, on questions of transaction costs and risk-coverage.

A transaction that one can profit from is also a transaction that one can lose from—remembering that gains-from-trade merely say one is better off making the trade, which may simply mean minimising the loss. The same applies to providing a good or service for sale. Covering the risk of loss is a fundamental factor for why firms exist and how they are structured. Even in illegal markets.

Different paths

The path of the People’s Republic from full command economy to extensive commercial economy—under the continuing rule of the Chinese Communist Party—sheds some light on another recurrent pattern in Eurasian history. That land starts as being owned by the ruler and, over time, becomes the property—with varying degrees of completeness and recognition—of intermediary social actors. This can extend all the way down to individual farmers.

Over time, for example, Japan moved from the Emperor owning the land under the Taika reforms (645)—copying Tang China (618-907) and the equal-field system—to any such Imperial ownership being entirely notional. But versions of this pattern happens in China itself, in Indian, European, Islamic history; in many societies. The modern pattern waves of nationalisations being eventually followed by privatisations is not a new cycle in human history. The difficulties and inefficiencies of central control—and the pervasive power of, and tendency towards more dispersed, acknowledged possession, of property-as-convention—are clearly recurring tensions within state societies.

Evidence suggests that, around 1700, South-Eastern China (the Yangtze delta), North-Western Europe (England and the Netherlands) and Tokugawa Japan all had relatively similar standards of living. (Japan perhaps a bit lower.) Given that Qing China was not a rule-of-law polity, it is clear that conventions, kin-group cooperation and local norms can support a great deal of commercial activity. Especially in areas the state has sufficiently pacified.

The above regions varied more in the quality of their law than they did in their standard of living. That was to change, as the dramatic increase in access to and use of energy we call The Industrial Revolution greatly increased the range of returns to processes of commercial discovery, coordination and risk management; to mobilising inputs (including labour and especially energy); and whether local interests vetoed or otherwise impeded such development. This all led to much sharper differentiation in economic outcomes between societies, as it created much greater potential variability in productive harnessing of energy.

Japan had a more highly developed legal culture than China. Japan had a long history of internal competitive jurisdictions and evolving mechanisms to arbitrate between competing, including armed competing, groups. (As also did medieval Europe.)

Japanese rule of Taiwan (1895-1945) was much more rule-of-law based than previous Qing rule had been. Japan, with its competitive subordinate jurisdictions, seems to have drawn ahead of China in provision of local public goods after 1650 (or possibly earlier). Tokugawa Japan c.1850 was sufficiently institutionally similar to North-Western Europe c.1450 that by “fast-forwarding” it could, and did, catch up with the West.

China suffered from its greater institutional distance in its attempts to adapt to the Western challenge. The difficulty in catching up is how to get from where you are to where you want to go. The more similar the starting point to already industrialised societies, the clearer the potential path.

Hence, in adapting to the Western challenge, institutional similarity—and cultural compatibility—has mattered more than geographical proximity. Middle Eastern Islam has spent its entire history being adjacent to European Christendom, yet still struggles with adapting to modernity far more than Japan, or other East Asian societies.

If we take institutions to be social infrastructure, Japan was advantaged by its social infrastructure being so similar to Europe’s, so it was able to adapt to the Western challenge much more effectively. Conversely, Islam and China were disadvantaged by their social infrastructure being quite different, so found it harder to replicate Western success.

Consider the so-called “Asian tigers”. Singapore and Hong Kong were British creations. Taiwan had been ruled by Japan, and was not inflicted with the disaster of Communist rule. Moreover, the Kuomintang refugees were chastised by their failure on the mainland. South Korea could and did adapt the Japanese example.

In many ways, the story of post-1978 China is the CCP attempting to overcome the disasters it had inflicted on China. Having, via the Western imports of Marxism and Leninism, attempted to dramatically institutionally diverge from the West—and suppress traditional Chinese culture—it now sought to reverse both doings.

The next post examines owning people and animals and the dynamics of regulation. The fifth and final post seeks to answer the original question of how China had a commercial take-off without rule of law or, until 2004, formal commercial property rights.

References

Books

Mikael S. Adolphson, The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan, University of Hawai’i Press, 2000.

Douglas Allen, The Institutional Revolution: Measurement and the Economic Emergence of the Modern World, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Yoram Barzel, Economic Analysis of Property Rights, Cambridge University Press, [1989], 1997.

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Amy Chua, Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations, Bloomsbury, 2018.

Michael J. R. Crawford, An Expressive Theory of Possession, Hart Publishing, 2020.

R. H. Coase, The Firm, The Market and the Law, University of Chicago Press, 1988. Includes ‘The Nature of the Firm’ (1937) and ‘The Problem of Social Cost’ (1960).

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377] 1967.

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Dieter Kuhn, The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China, Harvard University Press, [2009] 2011.

Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe, W.W.Norton,[1982] 2001.

Jens Ludwig, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies, trans. W.D.Halls, W W Norton, [1925] 1990.

Robert Neuworth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Harvard University Press, [1982] 2018 [SaSD].

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

John P. Powelson, Centuries of Economic Endeavor: Parallel Paths in Japan and Europe and Their Contrast with the Third World, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Philip Carl Salzman, Culture and Conflict in the Middle East, Humanity Books, 2008.

Michael J. Seth, Korea: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2020.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Mark S. Weiner, The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom, Picador, 2014.

Articles, essays, etc.

Plamen Akaliyski, Vivian L. Vignoles, Christian Welzel, and Michael Minkov, ‘Individualism–collectivism: Reconstructing Hofstede’s dimension of cultural differences,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2025) Advance online publication. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2027-01517-001.html

Richard E. Blanton, Gary M. Feinman, Stephen A. Kowalewski, and Peter N. Peregrine, ‘Agency, Ideology, and Power in Archaeological Theory: A Dual-Processual Theory for the Evolution of Mesoamerican Civilization,’ Current Anthropology, Volume 37, Number I, February 1996. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230760700_A_Dual-Processual_Theory_for_the_Evolution_of_Mesoamerican_Civilization

Stephen Broadberry, ‘Accounting for the Great Divergence: Recent findings from historical national accounting.’ Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers, Number 187, March 2021. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/accounting-great-divergence-recent-findings-historical-national-accounting

Arthur L. Corbin, ‘Legal Analysis and Terminology,’ The Yale Law Journal , Vol. 29, No. 2, Dec., 1919, 163-173. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9effd79b-398b-4935-aff7-45394cde96e8/content

Harold Demsetz, ‘Towards a Theory of Property Rights’, American Economic Review, Volume 57, Issue 2, May 1967, 347-359. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/38c0/4ebc14c2f5fc70a61f4521f6568522413a92.pdf

Lane F. Fargher, Richard E. Blanton, and Verenice Y. Heredia Espinoza, ‘Egalitarian Ideology and Political Power in Prehispanic Central Mexico: The Case of Tlaxcallan,’ Latin American Antiquity, 21(3), 2010, 221- 251. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261734943_Egalitarian_Ideology_and_Political_Power_in_Prehispanic_Central_Mexico_The_Case_of_Tlaxcallan

Alan Page Fiske, ‘The Four Elementary Forms of Sociality: Framework for a Unified Theory of Social Relations,’ Psychological Review, 1992, Vol. 99, No. 4, 689-723. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/21700623_The_four_elementary_forms_of_sociality_Framework_for_a_unified_theory_of_social_relations

Ashley Jackson and Florian Weigand, ‘Rebel rule of law: Taliban courts in the west and north-west of Afghanistan,’ ODI Briefing Note, May 2020. https://media.odi.org/documents/Rebel_rule_of_law_Taliban_courts_in_the_west_and_north-west_of_Afghanistan.pdf

Harry Frankfurt, ‘On Bullshit,’ Raritan Quarterly Review, Fall 1986, Vol.6, No.2.https://raritanquarterly.rutgers.edu/issue-index/all-volumes-issues/volume-06/volume-06-number-2

Adam K. Frost, Zeren Li, ‘Markets under Mao: Measuring Underground Activity in the Early PRC,’ The China Quarterly, 2023, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/markets-under-mao-measuring-underground-activity-in-the-early-prc/FCED40169CCA6DEEF21B48012BC4D38C

Yegor Gaidar, ‘The Soviet Collapse: Grain and Oil,’ AEI, April 2007, 2007-09 #21440, compiled from a lecture delivered by Yegor Gaidar at AEI on November 13, 2006. https://www.scribd.com/document/428148552/Grain-and-Oil

Clifford Geertz, ‘The Bazaar Economy,’ The American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Suppl.: Papers and Proceedings of the Ninetieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association) (May, 1978), 28-32. http://hypergeertz.jku.at/GeertzTexts/Bazaar_Economy.htm

David D. Haddock and Daniel D. Poisby, ‘Understanding Riots,’ Cato Journal, Vol.14, No.1 (Spring/Summer) 1994, 47-157. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/1994/5/cj14n1-13.pdf

Douglas A. Irwin, ‘Adam Smith’s “Tolerable Administration Of Justice” And The Wealth Of Nations,’ Working Paper 20636, October 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20636

Monika Karmin, et al., ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Resources, 2015 Apr;25(4):459-66. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381518/

Meir Kohn, ‘Money, Trade, and Payments in Preindustrial Europe,’ in S. Battilossi et al. (eds.), Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, Spring, 2018. https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-981-10-0622-7_15-1

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021). https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/alternative-theoretical-framework-economics

Arthur Lewis, ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,’ The Manchester School, May 1954. https://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/368/368lewistable.pdf

Debin Ma, ‘Rock, scissors, paper: the problem of incentives and information in traditional Chinese state and the origin of Great Divergence,’ Economic History Working Papers 37569, London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History, 2011. https://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/WorkingPapers/Economic-History/2011/WP152.pdf

Debin Ma & Jared Rubin, ‘The Paradox of Power: Principal-agent problems and administrative capacity in Imperial China (and other absolutist regimes),’ Journal of Comparative Economics, (2019), 47(2), 277-294. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/esi_working_papers/212/

Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Laurent Weill, ‘Is corruption an efficient grease?,’ BOFIT Discussion Papers, (2008) No. 20/2008, Bank of Finland, Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT), Helsinki. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/212633/1/bofit-dp2008-020.pdf

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Michael T. Rock, Heidi Bonnett, ‘The Comparative Politics of Corruption: Accounting for the East Asian Paradox in Empirical Studies of Corruption, Growth and Investment,’ World Development, Volume 32, Issue 6, 2004, 999-1017. https://afca.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Rock-Bonnett-2004-The-comparative-politics-of-corruption-Accounting-for-the-East-Asian-paradox-in-empirical-studies-of-corruption-1.pdf

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Coevolving institutions and the paradox of informal constraints,’ Journal of Institutional Economics, 2021, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/CE95D185B7EA557C5D0066FA7D785BCB/S1744137420000600a.pdf/div-class-title-coevolving-institutions-and-the-paradox-of-informal-constraints-div.pdf

Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘Size and dynastic decline: The principal-agent problem in late imperial China, 1700–1850,’ Explorations in Economic History, Volume 54, 2014, 107-127. https://conference.nber.org/confer/2011/CE11/Sng.pdf

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Chenggang Xu, ‘The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development’, Journal of Economic Literature, 2011, 49:4, 1076–1151. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227363166_The_Fundamental_Institutions_of_China’s_Reforms_and_Development

Jan Luiten van Zanden, Eltjo Buringh, and Maarten Bosker, ‘The rise and decline of European parliaments, 1188–1789,’ The Economic History Review, 2012, 65, 3, 835–861. https://www.academia.edu/20611214/The_rise_and_decline_of_European_parliaments_1188_17891

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw, & Marcus W. Feldman, “Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck”, Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04375-6

Prediction: the final conclusion will include the observation that China did have rule of law and property rights - they were just outside the country, but accessible, through increasing globalism and/or the cultural networks carried by diaspora communities. With HK mentioned in here somewhere.

Thank you for lots of readings and Happy Christmas & NY.

PS Apart from Bondi we've had another cultural quake this week with the Jacob Savage article in Compact, and its fallout. Looks like you're busy for a while but I'd love an opinion, particularly if the great rollback has begun. Robert Manne sounds afraid.

Sadly what Adam Smith characterized as universal was specific, at least in the sense of it as a product of experience and not theory. Heinlein better captures the universal...

“Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances which permit this norm to be exceeded — here and there, now and then — are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of a society, the people then slip back into abject poverty.

This is known as "bad luck.”