Property against the state

On acknowledged possession (2)

I became intrigued by how China managed to have a massive commercial take-off well before it legalised private commercial property (in 2004). I therefore wrote a 12,000 word essay on the origins and dynamics of property. That is far too long for a Substack post, so I have broken it up into a series of posts. (This post has been renamed, to make the content clearer.)

The first post established that property predates the state or the law. This post looks at how even formal property rights rely on pre-existing conventions; how remarkably universal such conventions are; how corruption operates; how connections matter; and how black markets are very revealing of the dynamics of property.

Owned things as bundles of attributes

It is useful to distinguish between control, in the sense of physical control, and control in the sense of right-to-decide. For instance, the notion of physically controlling land—outside of military or quasi-military contexts—is pretty tenuous. The notion of having the right-to-decide how land is used is much more straightforward. It is the latter sense that applies to property and is used in these posts—until we get to owning humans and other animals, when physical control again matters.

Owned things are bundles of attributes over which people exercise rights-to-decide. For instance, under slavery, the person is owned; under serfdom, their labour is owned (though that distinction can be fuzzy—see Russian serfdom). These may be formal (i.e. legally recognised) rights-to-decide or they may be informal (i.e. functional) rights-to-decide. The conventions of mutually acknowledged possession analysed in the previous post generate informal/functional rights-to-decide.

If there is no pacifying state, then there is what one might call a pure trade-or-raid (i.e., take) choice. Even then, there are many reasons that trades can and will still happen. This is especially so when people are engaged in repeated interactions. People can then evolve mechanisms for making costs and risks of transacting sufficiently manageable that trades can happen. This is greatly helped by the conventions of acknowledged possession being so useful that some form of them is universal across human societies.

A classic such trade-enabling mechanism is the use of connections to ascertain or develop a reputation, or to shame and shun delinquent actors. Such building on right-to-decide conventions enables trades to proceed, with the lack of state protection encouraging the development of alternative mechanisms to protect one’s holdings and to enable trades and other resource transfers to happen. Gift-transfer networks and norms around hospitality and guests were an example of such.

As various economists, such as Ronald Coase, Harold Demsetz and Yoram Barzel, have explored at length, a trade, an exchange, is actually a transfer of recognised possession—the mutually acknowledged right-to-decide—over some attribute or bundles of attributes.( A gifting is a one-way version of such.) Common law finds it easier to create differentiated rights-to-decide over attributes of an owned thing than does Roman (Civil) law, with its notion of property as dominion.

If such rights-to-decide are formally recognised, then they are legal or formal property rights. But humans were trading long before there were states.

Property is not a relationship between you and a thing. Property arises from recognition by others of your possession of a thing. Or, to put it another way, your authority over a thing.

But such authority can be acknowledged without (or even against) state recognition of the same. Even in the case of formal property systems, they rest on conventions of acknowledged possession. While economists have struggled to find strong connections between overall economic performance and formal property rights, they have persistently found evidence:

that informal norms are more important than formal rules in protecting property.

The key thing in property is not “mine!”—any silverback gorilla thumping his chest can claim that and all doing so creates is a contestable territoriality. The key thing in property is “yours!”: the acknowledgement by others that the thing is yours and remains yours until you pass it to another.

The conventions of acknowledged possession are the basis of property. Having signalled one’s possession, one’s authority over that thing—the right-to-decide—is presumptively established. The notion of “mixing one’s labour” with something is a particularly clumsy rendition of such signals and conventions.

Property does not become a matter of law unless there are remedies involved: i.e., one can take action before some adjudicating authority for breaches of your property and achieve restitution or compensation. The simplest way to understand legal ownership is as the dominant right-to-decide claim over a thing that is subject to remedies for its breach. Nevertheless, no matter how complex property law may become, it ultimately rests on the conventions of possession generating presumptive acknowledgement of the right-to-decide how something is used.

The ability to lend or rent out property indicates how ownership is not the same as possession. Possession takes something into the realm of property and signals presumptive ownership, the presumptive right-to-decide. But ownership allows one to rent or loan property to another, creating a form of subordinate possession.

Legal ownership provides a potential security of title—via third-party adjudicated remedies—that does not extend to illegal goods. That is the point of legal ownership: the provision and application of remedies by an adjudicating third party. One gets access to such adjudication at the cost of the application of the rules thereof. The higher the costs of the same, the more attractive informal—i.e. not-state-recognised—markets become. Where the state does not reach, they will be the only possible markets.

Property and the state

Eminent domain, land acquisition, compulsory purchase/acquisition, resumption, resumption/compulsory acquisition or expropriation, represent public authorities formally extinguishing existing recognised rights-to-decide—typically over land—for some public purpose. This is known in the literature as “takings”.

Regulation short of such explicit acquisition can generate such extensive right-to-decide by officials over attributes of something—so supplanting that of the putative owner—to thereby also constitute a regulatory “taking” of property. Both the Australian High Court and the US Supreme Court have attempted to adjudicate at what point regulation can constitute such a “taking”.

The who-gets-to-decide issue arises for any form of society. A command economy relies on property rights—on rights-to-decide—every bit as much as does the most mercantile, private commerce, society. A command economy has a top-down allocation of property rights, but the authority-to-decide has to be distributed among the agents and agencies of the state for any command economy to function.

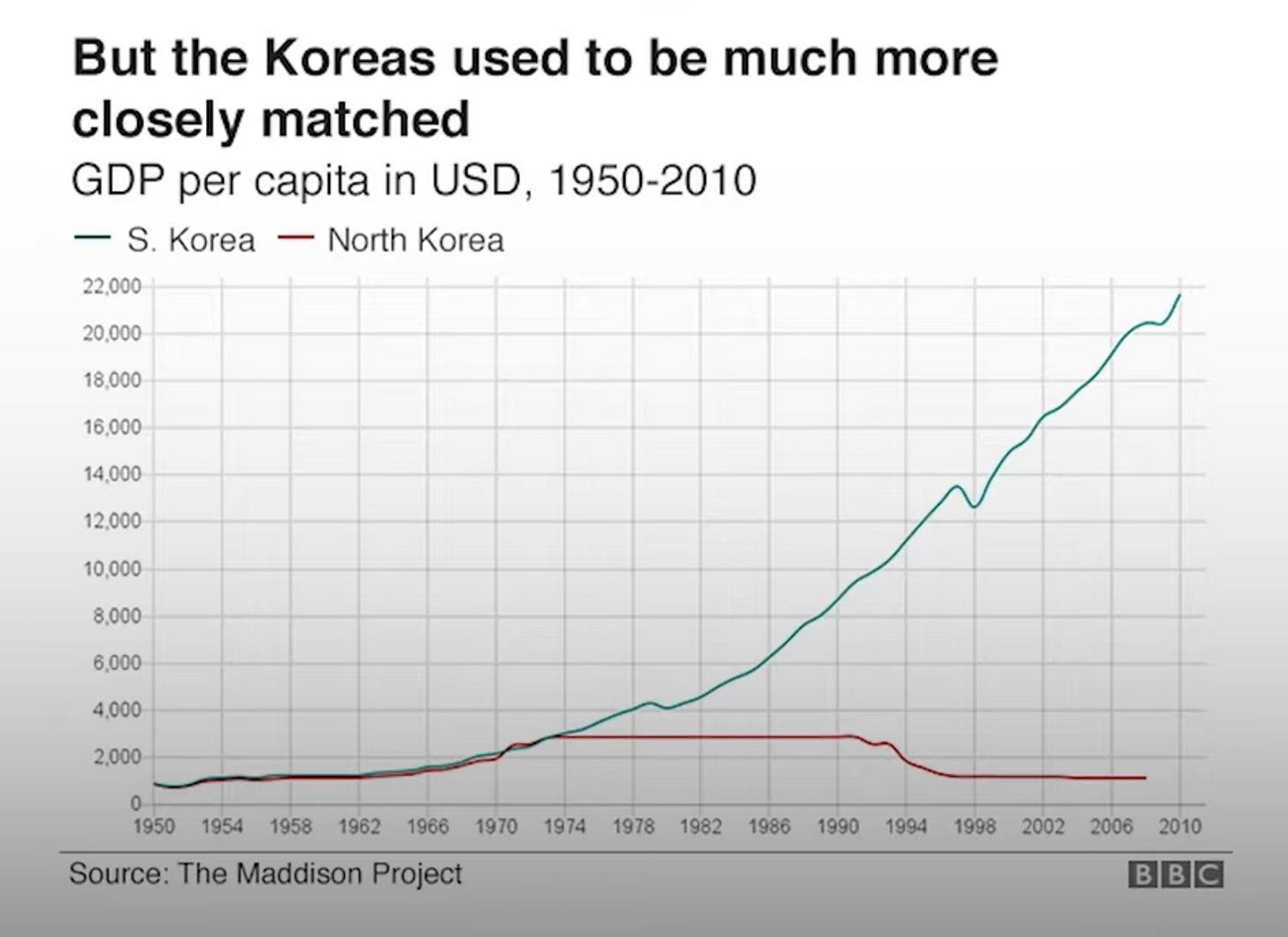

Not only that, even the most centrally-controlled command economy relies on conventions of ownership and can find its formal processes subverted by the same. In China, in the late 1970s, de-collectivisation of farming land—its breaking up into private farms—was mostly done as a bottom-up process among the peasants dividing up the collective farms. This occurred due to massive disruption of local Party control by the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976.

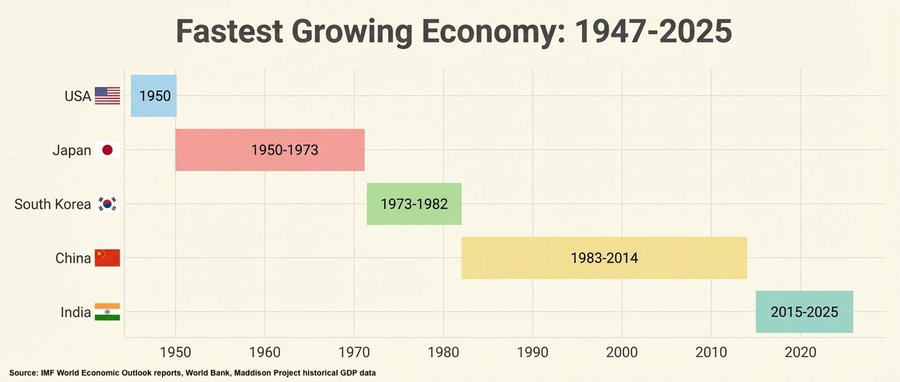

This was a bottom-up de-collectivisation of farmland that the Chinese Party-State eventually acquiesced in. It is one of the great ironies of history, that a process unleashed by an arch-economic-centralising collectivist (Mao Zedong), and admired by various Critical Theorists (such as Herbert Marcuse and Paulo Friere), led directly to the greatest expansion of private commerce in modern times.

This rural de-collectivisation became the model for processes of commercialisation in China that operated for years before the institution of legally-acknowledged commercial property rights in 2004. There was more than enough mutual acknowledgement of ownership, including by state officials, for commerce to operate. Legal acknowledgement was clearly not required.

As is discussed in the next [and a later] post, China has a long history of people finding ways to avoid entanglement with the legal apparatus of the state, including its courts, while engaging in extensive commerce. This was very different from Europe’s institutional development (or, for that matter, Japan’s).

Thus, the Western translation of Fajia (the school of fa) as Legalism is somewhat misleading. The Chinese notion of law—instructions given to officials to enforce—is rather different from the Roman (Civil) Law or Common Law traditions, or even Sharia.

Like the other civilisations with strong philosophical traditions—the Indic and Hellenic—China has a weak legal tradition. The very practical Romans and English generated much stronger legal traditions.

Property against the state

In the modern world, informal markets come in two general forms. One is markets in goods and services that are not as goods or services illegal, but the buying and selling of them is either illegal or in some other way lacks the formal recognition of the state. This includes disregarding various intellectual property (IP) rights in so-called grey markets, though that term can be applied more widely to any informal market that is not outright illegal in both goods and services and in their exchange. The other form of informal markets are black markets, where the goods or services themselves—including the private possession thereof—are illegal, so trading them is also illegal.

Informal markets—whether black or grey—demonstrate that state recognition and protection of property rights and their exchange is not required for a market to operate or for property to exist, even within the territory of a functioning state.

If the state bans the sale and/or purchases of specific goods and services, that means that the normal legal protections are not available. The state does not merely fail to provide recognition and protection of property rights within the banned exchanges, or any mediation or adjudication services for them. The state actively denies such and seeks to suppress the trades. It if outright bans goods or services, it is also seeking to suppress the accompanying property rights.

Yet, black markets exist. They can even flourish, generating great—if insecure and often violently contested—wealth. They are part of the wider informal economy of economic activity that is not regulated or protected by the state.

That black markets are actively illegal makes them a particularly revealing manifestation of how property operates. The power of mutual acknowledgement—and of information-economising, expectation-aligning, common presumptive expectations—is such that it permits black markets to operate even though the state is seeking to actively frustrate such mutual acknowledgement and exchanges.

Black markets can only operate because the state is unable or unwilling to make its bans fully effective. But the difficulty of doing so points to—and is partly a result of—not only the willingness of the parties to make the banned exchanges, but that they can utilise conventions of mutually acknowledged possession to do so. One gets the operation of property against the state.

Black market exchanges are not tapping into something odd. They are simply replicating the normality of property as conventions of mutual acknowledgment of possession, albeit in defiance of the state and of law.

Such conventions of mutual acknowledgement can enable commerce to function, even flourish, when the legal system is highly dysfunctional. India, with its notorious decade-long delays in hearing court cases, is very much an example of this.

The distinction between illegal transactions and illegal goods also matters. If a good is illegal to own, there is no legally binding—i.e., positively evidentiary in law—signals of possession, as there is no legally recognised owners. But there is a functional possessor and that is enough for convention(s) of use and transfer to operate through creating presumptive ownership via mutual acknowledgement. Indeed, prosecuting folk for possessing illegal goods itself requires a ubiquitous, pre-state, pre-law convention of possession. That, in itself, is a stark admission that property is pre-law.

Just as connections can be used to enable trades to take place in the absence of the state, they can do the same against the state. Serious corruption, for example, usually operates in networks. These can provide mutual support, mutual guarantees and mechanisms to sanction members.

Connections are at least as important as transactions in understanding social—and even economic and commercial—behaviour. It is precisely because connections can trump transactions as a more efficient and/or resilient mechanism to produce, and distribute, goods and services that firms exist. The boundaries of the firm are not only the boundary of whether internal connection or external transaction are preferable in terms of cost and reliability; it is also the boundary for the coverage of risks by the owner(s). These considerations also apply for organised crime networks and gangs.

Even ordinary transactions are commonly embedded in connections. That is how bazaars operate, for example. Traders develop connections of information, reputation, commitment and repeated exchanges.

The reason why friends, relatives, acquaintances is persistently the most important labour market intermediary is not merely from the flow of information along such connections. It is also because the intermediary acts as an implicit guarantor, as folk can both have a view about the intermediary’s reliability in judgement and they can expect that they value the connection enough not to make a dud recommendation. Similar mechanisms can operate in exchange networks outside the ambit of the state or against the ambit of the state—including in corruption networks.

The importance of connections (aka social capital) is why it makes a difference if one’s connections are overwhelmingly local or if they are far more geographically dispersed. People whose connections are overwhelmingly local are going to have a very different view of the world than those whose connections span continents. This has become a key fracture line in contemporary politics.

The power of connections is very much tied up with how property operates, and can operate, across different social contexts.

Connection, corruption and culture

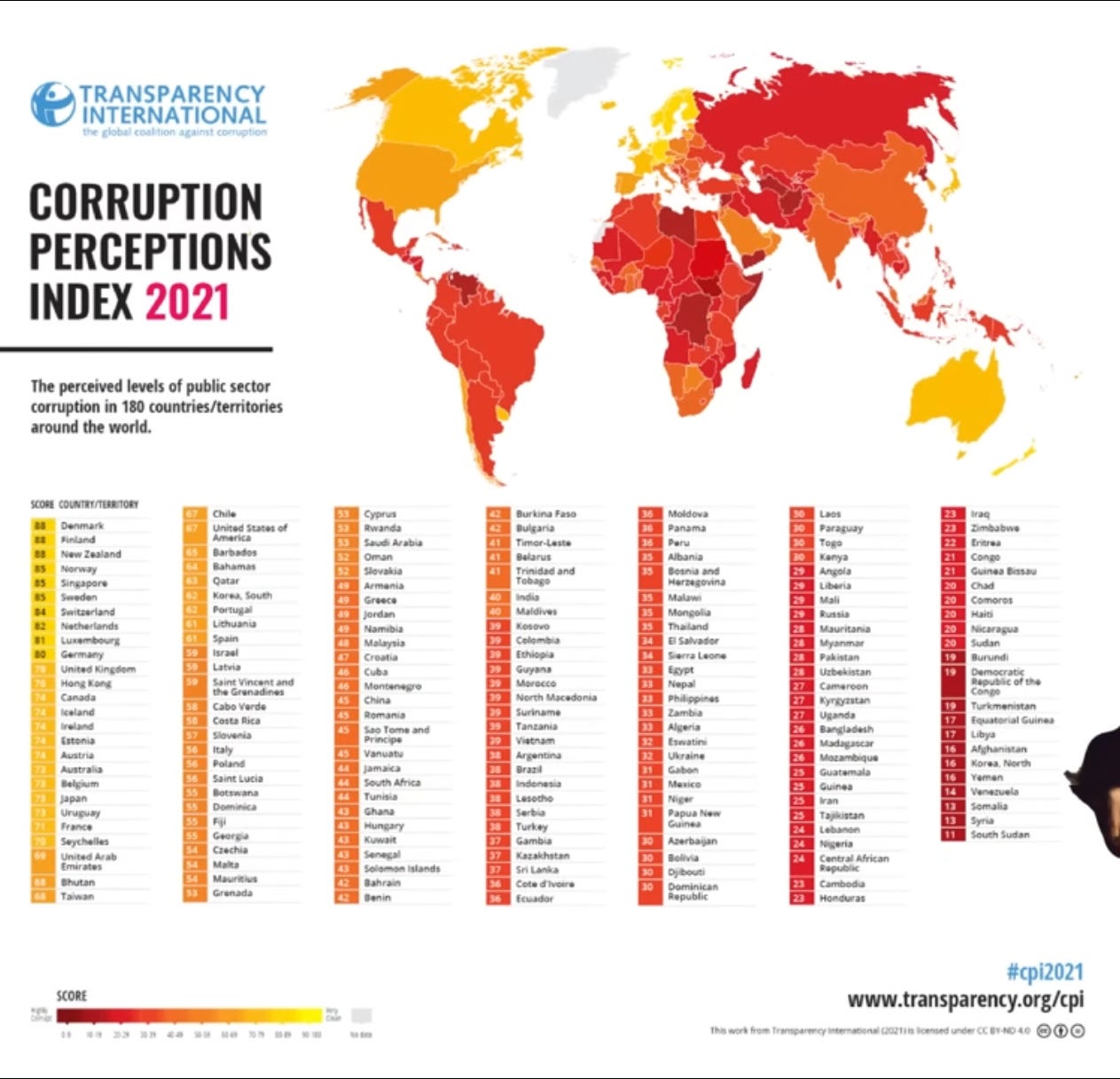

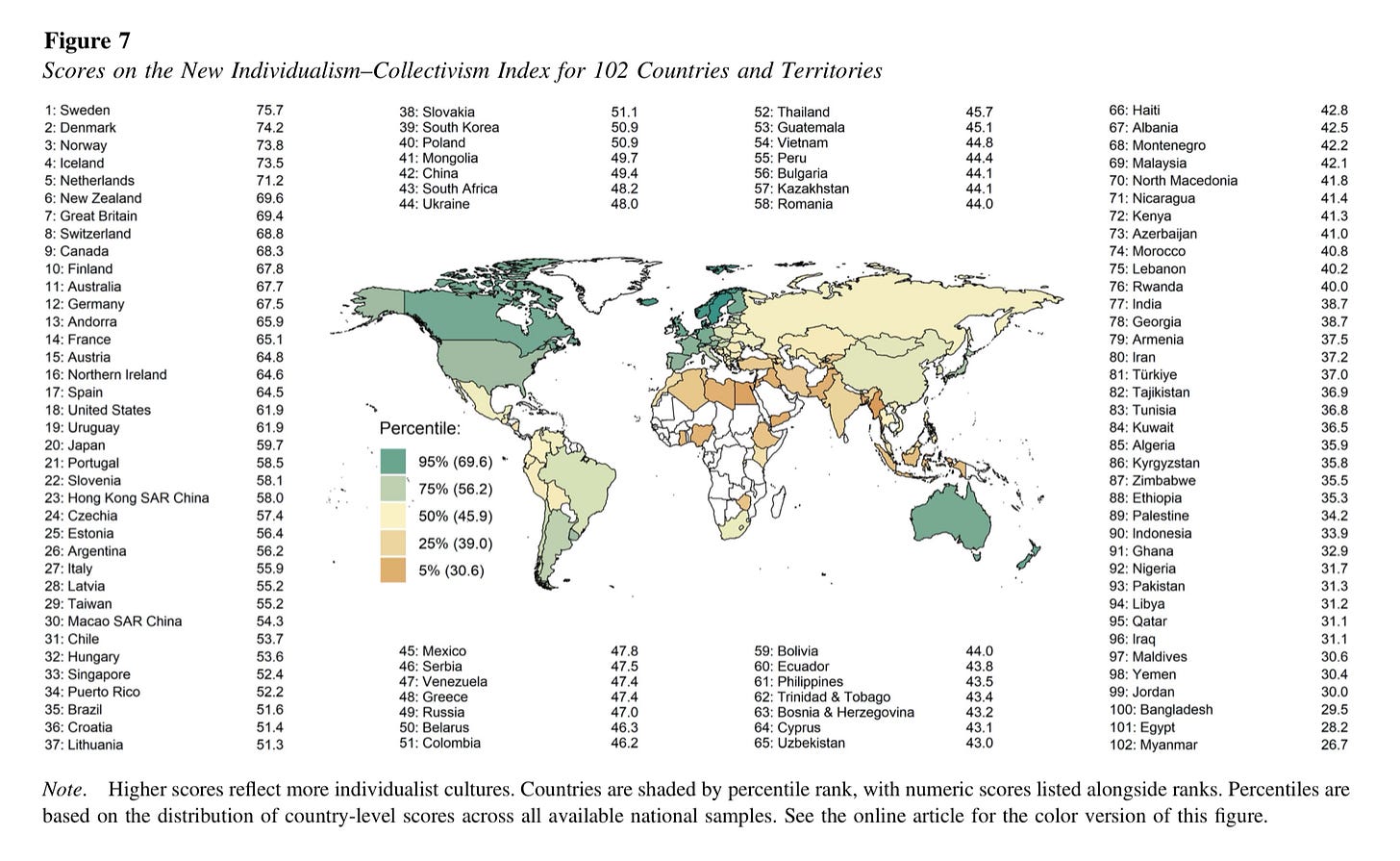

Corruption is very highly correlated with cultural collectivism. That is, the more in-group connections are valued in a society, the higher the rate of corruption in the state, at an almost linear rate (0.91 correlation).

This can be a matter of officials favouring in-groups directly, with officials discretions being incorporated within, and as part, of gift-transfer networks. It can also be out-groups suffering what is in effect an “out-group tax” of bribes being required to get necessary official approvals. As a recent study notes:

large-scale studies have repeatedly shown that social trust, social solidarity, cooperation, civic participation, and even altruism are more prevalent and extend across a wider social radius in individualist than in collectivist societies.

The multi-billion dollar Minnesota welfare fraud scandal shows Somalis acting as, well, Somalis: people from a very clannish and collectivist culture. The real scandal is how political patronage; mainstream media toxically eager to engage in moral abuse (Racist! Xenophobic! Islamophobic!); and cowardly—I am sorry, risk adverse—bureaucrats enabled Somali culture to subvert American institutions. It is a salient example of how the key issue with immigration in Western countries is the mismanagement of the same by Western elites—particularly when dealing with culturally incompatible immigrants.

While cultures evolve, they also generate quite different patterns of behaviour. Such evolution tends to be generational, as adult cultural patterns tend to be relatively fixed. Nor can it be presumed such evolution will be towards a host society—second-generation immigrants can become more, rather than less, alienated from a host society.

Nevertheless, one of the striking things about property is precisely how universal conventions of mutual acknowledgment are. To use the language of game theory—as applied in Michael Crawford’s greatly clarifying An Expressive Theory of Possession—conventions of possession readily and commonly ascertain, with regard to any possess-able thing, who is Hawk and who is Dove. Who decides (Hawk) and who defers to that deciding (Dove).

In other words, who has authority over that thing. Hence the need for simple and salient information as signals of possession creating conventions of possession that all can use. Any of us can go to any local market or bazaar anywhere in the world and understand the basic operation of property therein via mutual acknowledgement of possession. That commerce has such universal patterns helps explain why economists can be so blind to the significance of culture, especially (but not only) in non-commercial settings.

Locality and black markets

Because the parties involved seek to avoid the prohibiting efforts of the state, black market exchanges tend to gravitate towards places that are not regularly policed by the state. The level of black market activity in a locality tends to say more about the distribution of the policing efforts of the state than the inhabitants of the locality.

Nevertheless, it is very easy for the inhabitants of such localities to be tarred by the association with the local black market activity. Such tarring can be useful to obscure the level of state responsibility for its (lack of) effective policing. It can be even more useful for dividing residents, citizens and workers by locality, or by features associated with locality.

In practice, even the blackest of black markets is somewhat parasitic on the formal property rights structure endorsed or provided by the state, if only to more securely enjoy the benefits of income and assets acquired from illegal exchanges. Hence the appeal of money laundering: converting what is illegal into what is legal by moving assets and income out of the realm that the state seeks to ban into the realm that the state acknowledges (i.e. ratifies) and protects. Obviously, the intent of such laundering of money and assets is to avoid the risks and costs of hostile state action, but successfully doing so also gains the benefits of state property-protection and adjudication services.

Note that such money laundering is not a movement from a realm without property to a realm with property. It is a shift from merely-conventional property to also formally-legal property.

One way to think of the distinction between purely conventional property rights and legal property rights is between economic property rights—what one functionally (due to conventions or other rules) has right-to-decide over—and legal property rights; what there are legal remedies for breach of. Economic property rights do not require law. Thus, slaves—being legally property—usually could not legally own property. But there are lots of cases of slaves having conventional—that is economic—property.

Economic property rights can also be created by law. For instance, by regulation requiring legal approval (such as licensing) for certain actions. In that instance, regulation creates a form of economic property right—specifically, regulation-created control by an official over some attribute, even though the law does not make them the legal owner of said attribute. The law grants them authority without ownership.

One of the problems of regulation is precisely that it can disconnect the right to decide from the costs and other consequences of decisions. This is, of course, a form of the principal-agent problem that bedevils all bureaucracies: government, corporate or non-profit.

The efforts of Trump 2.0 to enforce his authority over the Executive Branch of the US Government that he and the Vice President are the only elected members of—the authority of which is Constitutionally vested in the President—has very much exposed how, even in formally democratic states, networks can operate to control and divert resources. Indeed, the ostensible democratic nature of the state can provide useful legitimising of such control and diversion—including into various levels of political activism.

The creating and tapping into such networks encourages advocacy politics that by-passes electoral processes, creating the non-electoral politics of institutional capture. Often, when folk refer to “Our Democracy” they either mean the democracy of those who agree with us, or the politics of embedded networks living off taxpayer funds (or both).

There are two levels of corruption. One is straightforward bribery. This is the corruption that is endemic in kleptocratic regimes such as contemporary Russia and is measured by the Corruption Perceptions Index.

The other level of corruption—better thought of as parasitic diversion—is legal, but represents resources benefiting various players in excess of what is needed to achieve the ostensible aim of the expenditures. This is endemic in the developed democracies, to varying degrees. It is a different way for the state apparatus to be parasitic.

A particularly egregious example in the US is the homelessness-industrial complex where public funding perpetuates, even exacerbates, the homelessness problems it is ostensibly attempting to solve. Those paid to deliver processes have a vested interest in such processes continuing indefinitely and, ideally, expanding.

As (bribery) corruption is the market for official discretion, it is not surprising that high levels of regulation can generate high levels of corruption. The more regulation there is, the more (valuable) legal discretion there is to be potentially purchased.

The extensive literature on the economic effects of such corruption overwhelmingly finds that it has a negative effect. The evidence is strongly against the efficient corruption hypothesis which argues that corruption can increase economic efficiency by reducing the regulatory and bureaucratic “drag” effect on economic activity. (What we might call transaction friction.)

There are two notable exceptions. A study first published in 2008 found evidence for corruption having a positive effect on economic efficiency, but only in countries with sufficiently poor governance structures: corruption was otherwise detrimental.

The same study also found evidence that ethnic homogeneity was associated with higher economic efficiency: a plausible result as more shared framings, connections and expectations makes transacting easier and less risky. The mismanagement of Muslim immigration in Western Europe that is degrading or destroying customary Christmas markets is a case in point.

A study published in 2004 found that corruption was particularly economically detrimental in small economies. It also found that larger East Asian states with strong states—where political actors with long-term perspectives were able to dominate client networks—had a positive connection between corruption and economic growth. Such circumstances generated political connections motivated to support commerce—so clear rights to decide and reliable exchange, including contract enforcement.

The corruption-as-detrimental literature overlaps with the extensive literature finding economic freedom—that is, the less transaction friction government creates—to be positive for economic growth and living standards. The more clarity and reliability there is in rights-to-decide over what aspect of what, and the exchange thereof—including reliable contract enforcement—the lower transaction friction will be.

As command economies are massively pervaded by official discretions, they tend to become highly corrupt. A process aggravated by the rigidities of central control encouraging local “arrangements” to work around such rigidities.

Either way, that conventions of acknowledged possession are so readily available enables command economies to generate—even become increasingly pervaded by—black markets. The surreptitious development of such markets is part of why command economies proved more resilient than Austrian school economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek expected when they pointed out the information failures of command economies—what is known as the economic calculation problem.

They were right in the general point, they just underestimated people’s capacities to adapt to the failures of command economies—including (in some ways especially) via black markets. These adaptations allowed command economies to not collapse as readily as von Mises and Hayek expected.

Nevertheless, once command economies completed adding-inputs-to-manufacturing—mainly via shifting peasants into factories—those information and incentive failures still led to increasing stagnation and dysfunction. Command economies lack reliable mechanisms to eliminate value-destroying patterns provided in mercantile societies by loss and bankruptcy. (Insufficiency of mechanisms to eliminate value-reducing/destroying patterns is a general problem in public sectors.)

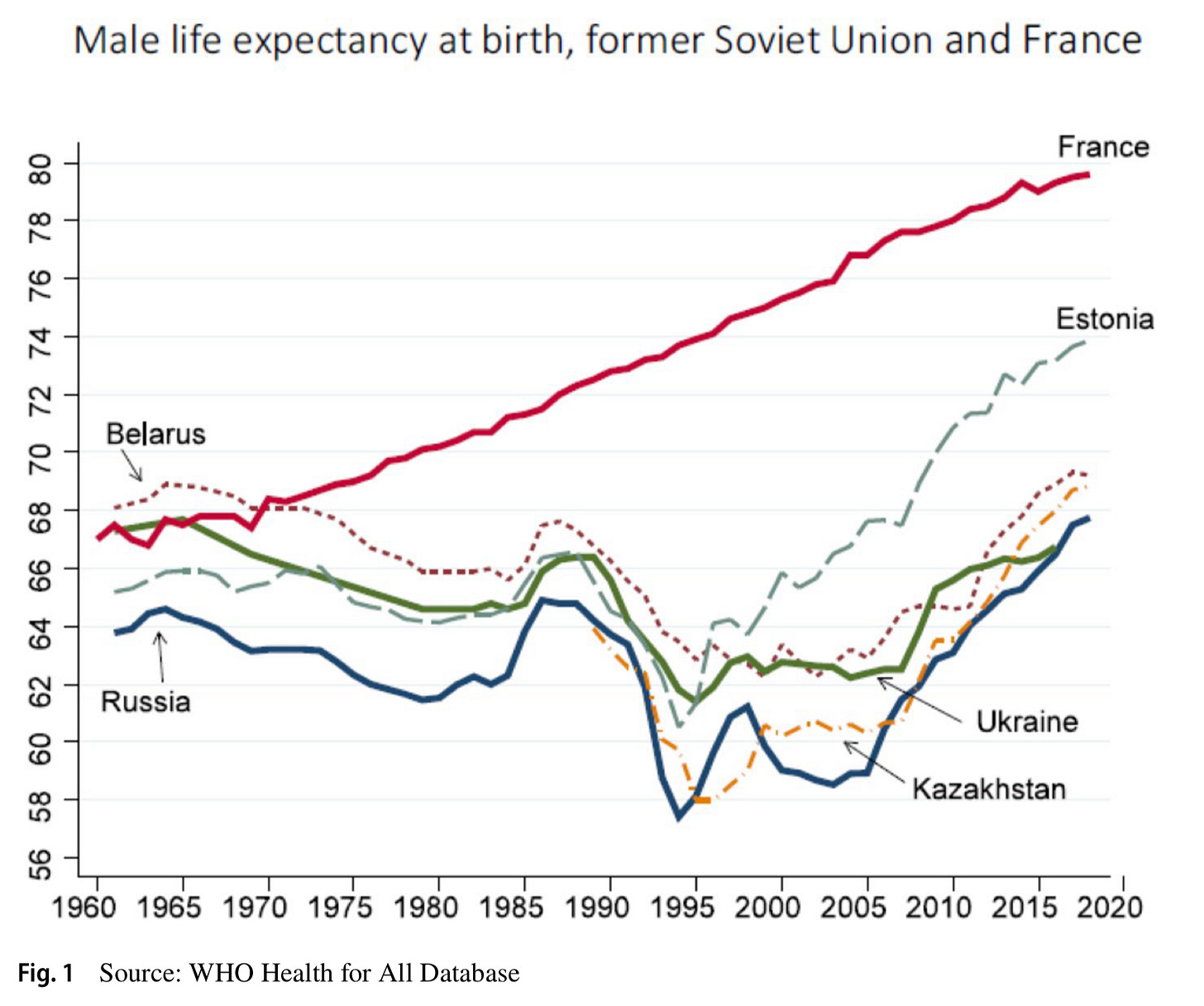

Stagnation and increasing dysfunction led the Soviet Union to collapse under its own weight of failure: epitomised by the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

Commerce without state sanction

As we have seen, informal markets extend beyond black markets. That networks of exchange outside the ambit of a state can exist, even flourish, demonstrates that commerce does not need the support and acknowledgment of the state to function. This does not then mean that there can not be major benefits in such support and acknowledgment—including the various services the state may offer. Though the extent of such informal exchanges point to potential or actual costs from such visibility to the state.

Even if the state is purely motivated by the social pacification needed to secure its revenue base, such pacification efforts of states and rulers typically involved providing or supporting adjudication services, support for local enforcers of order and suppression of armed groups. Historically, self-governing cities had city watches, or equivalent, such as the vigiles of Imperial Rome. Such efforts created pacified social spaces where exchanges and commerce could flourish.

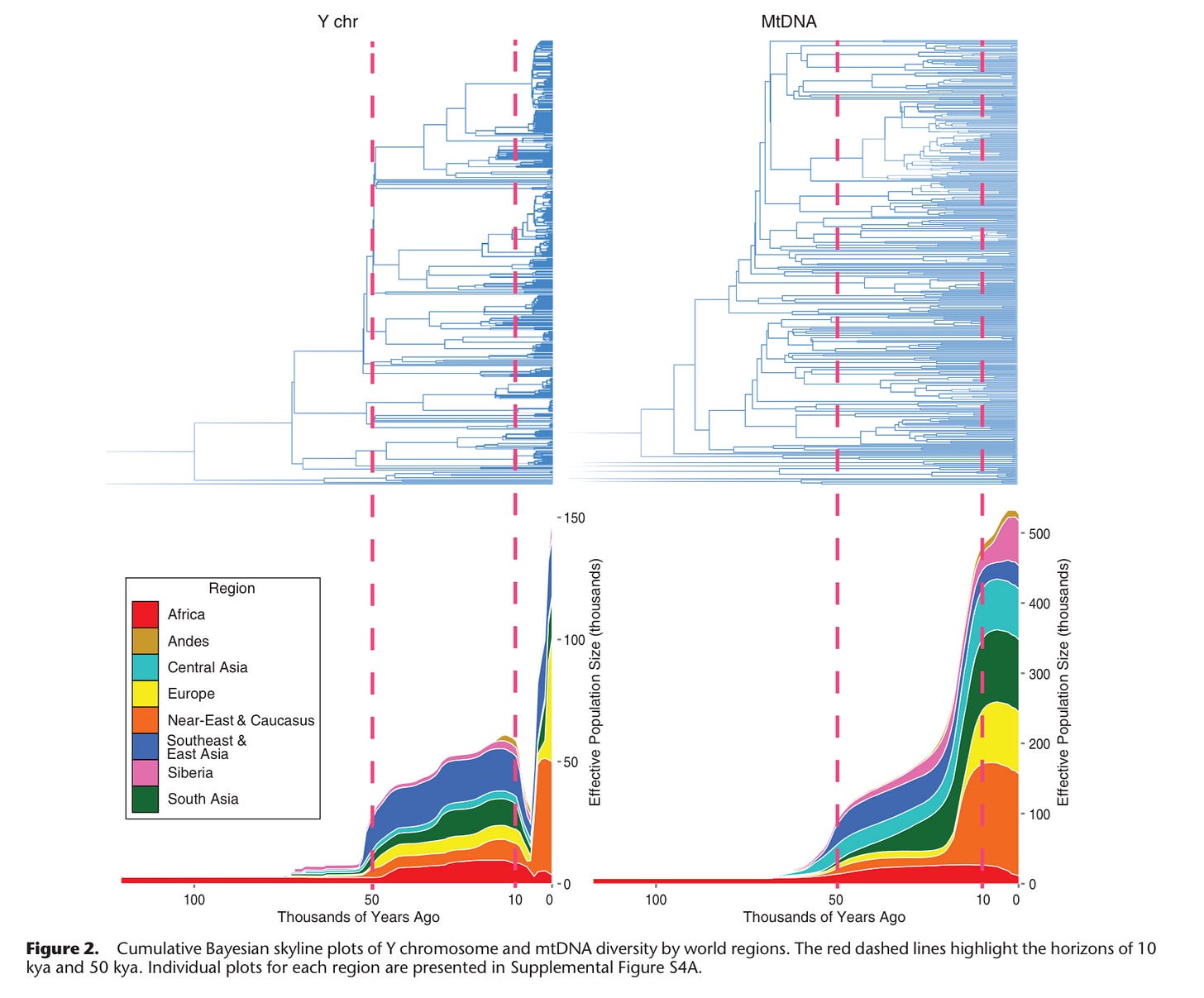

Nor should we be in any doubt about the value of the pacifying actions of the state in reducing violence, as it shows up quite clearly in the genetic record. In the period after the development of farming and pastoralism (so vulnerable assets), when population densities, and so kin-group competition, reached critical mass, there was such a harrowing of male lineages that only around 1-in-17 male lineages made it through the Neolithic y-chromosome bottleneck.

This harrowing of male linages only tapered off with the development of chiefdoms and states, so defeated males could be usefully taxed rather than killed or enslaved and their women taken. (There is no shrinkage in female mitochondrial lineages, who were clearly the “spoils” of the violent competition: it is a purely male-lineage bottleneck.)

We can see the centrality of revenue collection for state pacification by looking at patterns of crime by locality, including within developed democracies. A major reason particular localities in contemporary societies are under-policed—and so more likely to host black-market activity—is them being fiscal sinks: that is, the locality costs the state more in expenditure than it provides in revenue. Being a fiscal-sink locality undermines the revenue incentive to invest in the pacification—i.e. policing—of such localities.

Even without the net revenue cost problem, such localities tend to be bereft of the elite/articulate networks that encourage protective state action. One reason that the 2005 Cronulla riots happened at Cronulla is that it was one of two Sydney beaches near railway stations. But, the other—Bondi beach—was much better plugged into elite networks, so well-policed, while much more working-class Cronulla beach was markedly less so. Lebanese Muslim males kept harassing beach-goers and lifesavers, until local resentment exploded in the riots. Anti-hoon laws, that included penalties up to having your car confiscated and crushed, were a legislative response.

The pattern of under-policing fiscal-sink localities—an under-policing most directly measured by the variance in homicide clearance rates by locality—is particularly obvious in the shanty-towns of the developing world, especially in the Americas. It can also been seen in high-welfare localities in the developed world—notably in the distressed urban localities of the US, France and elsewhere.

As noted, such under-policed localities are where black market activities are likely to gravitate to, precisely because they are under-policed. Such localities are also likely to develop “bravado cultures” where young men in particular signal their willingness to defend their social space, their “rep”, by violence if necessary. Such increased reliance on private deterrence—due to under-provision of policing services—leads to much higher levels of violence in such localities.

Trade or raid

Black markets are, of course, notoriously connected to violence. This flows directly from the state actively seeking to block black-market exchanges and property, increasing the risks involved and so the use of private force to protect assets and resolve disputes. Especially when the banned goods are very valuable.

In the wider informal economy, in the absence of state recognition and adjudication, property has to be protected, and disputes resolved, by private action. Shaming and shunning can be quite effective sanctions within local social orders with locally supported or tolerated goods and services. Thus, networks of connection, with associated information flows, can protect and facilitate transacting, by operating as risk-management mechanisms.

Market exchanges happen through mutually acknowledged control of property. Such acknowledgement can be withheld or withdrawn, as can willingness to trade.

Crime gangs can increase the ability to protect one’s illegal trades but they also increase the ability to (violently) increase market share by killing competitors—with whom they are not trading—to take over their customers.

Exchanges outside the ambit of state ratification, protection and public adjudication are in the pre-state situation of the primordial trade-or-raid choice. Does one bargain to secure desired things that another has by trade or does one simply take by raid? Exchanges embedded within ongoing connections are much more likely to involve mutual acknowledgement.

Much of the point, and a very large part of the value, of state pacification is to minimise the attractiveness, and so incidence, of the take-by-raid choice. Such minimisation thereby elevates the frequency and scale of the gain-by-trade choice.

The taking (i.e the taxing) of government-funded pacification can thereby lead to less taking by other actors, so more making and trading of things able to be taxed. The revenue motive powerfully encourages state pacification. Pacification efforts that are, as we have seen, often weakened when the revenue motive is weakened or absent.

States may be the most potentially dangerous of social predators but they are also very useful in suppressing other social predators. A paradox that can never be solved, merely managed more or less well. One that all state societies wrestle with, with fluctuating degrees of success. Something noted by the first and greatest historical sociologist, ibn Khaldun (1332-1406):

Mutual aggression of people in cities and towns is thus averted by the authorities and by the government, which hold back the masses under their control from attacks and aggression against each other. They are thus prevented by the influence of force and governmental authority from mutual injustice, save such injustice as comes from the ruler himself. (Muqaddimah, I:2:7)

The trade benefits of state pacification does not only apply within states. It being much cheaper to move things by water than by land, the vast majority of world trade is water-borne, particularly ocean-going. Water—like money, peace, cultural homogeneity, economic freedom, good social infrastructure (institutions), and good physical infrastructure—reduces transaction friction.

It is, therefore, not remotely a coincidence that the first great age of mass globalisation—from the development of steamships and railways in the 1820s until the conflagration of the 1914-18 Dynasts’ War—coincided with British naval hegemony. Nor that the second such age—after the end of the 1939-45 Dictators’ War—has coincided with US (and allies) naval hegemony. In both eras, the dominant maritime hegemon also provided the dominant reserve currency.

The pacifying benefits of the Royal Navy and the US Navy (and its maritime allies) have been as central to each period of globalisation as any technological or institutional development. The central strategic paradox that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) currently wrestles with is that it seeks to challenge US hegemony, and its associated liberal-democratic norms. Yet China is a major importer of food and energy, so dependent on the oceanic pacification provided by the naval hegemony of the US and its allies. Hence the Belt-and-Road Initiative: creating trade and transport infrastructure that provides land-based access to food and energy or simply avoids various maritime choke-points.

Nevertheless, it is another of the ironies of history that the various levels of state pacification can generate, not only exchanges with property protected by state adjudication and enforcement mechanisms, but also expand the ambit of property and exchanges without state sanction, or actively against it.

The next post [looks at how property is embedded in other conventions, types of property, and paths of state action. The fourth post analyses ownership of people and animals. The fifth and final post] considers how China from 1978 to 2004 could have ever more private commerce, yet not have formal property rights.

References

Books

Yoram Barzel, Economic Analysis of Property Rights, Cambridge University Press, [1989] 1997.

Michael J. R. Crawford, An Expressive Theory of Possession, Hart Publishing, 2020.

R. H. Coase, The Firm, The Market and the Law, University of Chicago Press, 1988. Includes ‘The Nature of the Firm’ (1937) and ‘The Problem of Social Cost’ (1960).

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377] 1967.

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Jens Ludwig, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Robert Neuworth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, Harvard University Press, [1982] 2018.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Fei Xiaotong, From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society, trans, with an introduction and epilogue by Gary G. Hamilton and Wang Zheng, University of California Press, 1992.

Article, essays, etc.

Plamen Akaliyski, Vivian L. Vignoles, Christian Welzel, and Michael Minkov, ‘Individualism–collectivism: Reconstructing Hofstede’s dimension of cultural differences,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2025) Advance online publication. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2027-01517-001.html

Elizabeth Brainerd, ‘Mortality in Russia Since the Fall of the Soviet Union,’ Comparative Economic Studies, (2021) 63: 557–576. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8553909/

Arthur L. Corbin, ‘Legal Analysis and Terminology,’ The Yale Law Journal , Vol. 29, No. 2, Dec., 1919, 163-173. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9effd79b-398b-4935-aff7-45394cde96e8/content

Harold Demsetz, ‘Towards a Theory of Property Rights’, American Economic Review, Volume 57, Issue 2, May 1967, 347-359. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/38c0/4ebc14c2f5fc70a61f4521f6568522413a92.pdf

Yegor Gaidar, ‘The Soviet Collapse: Grain and Oil,’ AEI, April 2007, 2007-09 #21440, compiled from a lecture delivered by Yegor Gaidar at AEI on November 13, 2006. https://www.scribd.com/document/428148552/Grain-and-Oil

Clifford Geertz, ‘The Bazaar Economy,’ The American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Suppl.: Papers and Proceedings of the Ninetieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association) (May, 1978), 28-32. http://hypergeertz.jku.at/GeertzTexts/Bazaar_Economy.htm

Douglas A. Irwin, ‘Adam Smith’s “Tolerable Administration Of Justice” And The Wealth Of Nations,’ Working Paper 20636, October 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20636

Monika Karmin, et al., ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Resources, 2015 Apr;25(4):459-66. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381518/

Arthur Lewis, ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,’ The Manchester School, May 1954. https://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/368/368lewistable.pdf

Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Laurent Weill, ‘Is corruption an efficient grease?,’ BOFIT Discussion Papers, (2008) No. 20/2008, Bank of Finland, Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT), Helsinki. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/212633/1/bofit-dp2008-020.pdf

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Duane Ostler, ‘Gain as loss: The High Court’s approach in regulatory acquisition cases,’ Bond Law Review, (2015) Vol. 26: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/BondLawRw/2014/3.pdf

Michael T. Rock, Heidi Bonnett, ‘The Comparative Politics of Corruption: Accounting for the East Asian Paradox in Empirical Studies of Corruption, Growth and Investment,’ World Development, Volume 32, Issue 6, 2004, 999-1017. https://afca.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Rock-Bonnett-2004-The-comparative-politics-of-corruption-Accounting-for-the-East-Asian-paradox-in-empirical-studies-of-corruption-1.pdf

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04375-6

You probably didn't intend this but such analysis is very relevant to the newly emerging "fintech" such as cryptocurrencies. On a conceptual level they exist in the same gray area that is ostensibly outside govt control, but parallel to the formal economy.

I've had a lot of arguments with techno-utopians countering the claim that its possible to have a currency genuinely outside of govt control, even if this were technically producible. My main argument line is that money carries value largely because the state is capable of enforcing debt obligations. (If not the state then at least hired goons). Without such a guarantee whatever financial object used to trade (blockchain or beads) cannot carry value.

Why did you use - coin? - the terms "the Dynasts War" and "the Dictator's War"? If you already wrote a substack about it, Substack search is not being helpful, sorry.