It’s not the deep state, it’s just bureaucracy

About the UK 2024 general election.

I dislike the term “the deep state.” It mystifies what is much more straightforward, even bland: how metastasising bureaucracy is undermining the resilience of Western societies and their political systems.

The British Labour Party has won a massive Parliamentary majority in the House of Commons even though its total votes fell: from 10,269,051 in 2019—32.1% of total votes—to 9,704,655 in 2024—33.7% of total votes. Labour’s massive Parliamentary majority is not a product of enthusiasm for Labour, but the fracturing of the votes of its opponents.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) vote fell dramatically—from 1,242,380 votes in 2019 to 724,758 in 2024. This was largely a casualty of the SNP embracing the genderwoo of Transactivism [and, as a helpful commenter below pointed out, political scandal]. Outside some narrow urban enclaves, no one votes for “woke” but, given a genuine opportunity, folk will vote against it. As Scots have.

The Liberal Democrats did very well, as they have a regionally concentrated vote—which, this time, they targeted properly—and disgruntled (posh) Shire Tories will protest vote Lib-Dem. Clearly, lots did.

The Tories did so badly because their already low vote was further reduced by the Reform vote surge. The Reform vote represented voters punishing the Tories for their failure to do anything they had promised. As political scientist Matt Goodwin puts it:

They failed to control our borders.

They failed to lower legal immigration.

They failed to cut taxes and the size of the state.

They failed to take on woke, exposing our children to ideas with no basis in science.

And they failed to level-up the left behind regions.

It is hard to think of any political Party that has so relentlessly thrown away its political mandate.

So, an angry, unhappy electorate (rightfully) punished two governing Parties (Tories and SNP) and has given Labour a massive majority, with little enthusiasm—almost two-thirds of voters voted for someone else—on a relatively low turnout.

There is, however, a deeper institutional issue underlying these results. Why are voters so disgruntled? Why did the Tories fail so spectacularly?

The answer to these questions is a mixture of how institutions have evolved, the development of media culture, the Anywhere-Somewhere divide and technocratic delusions.

Technocratic delusion

The technocratic delusion is multi-layered. It holds that governing is a managerial input-output problem, government bureaucracy simply implements policy, and that politics is not a motivation and coordination problem.

None of these presumptions are true, so technocratic politics fails. It does not connect to voters and does not understand, or grapple with, the actual institutional landscape.

The technocratic delusion is a way for clever people to be spectacularly clueless. Not the only such mechanism in the modern world.

Anywheres over Somewheres

The Anywhere-Somewhere divide is pervasive: the divide between people whose lives and identities are based on locality (Somewheres) and those whose identity is based on credentials, with networks not based on locality (Anywheres). Technocrats are Anywheres who have no clue that their experience and framings are vastly different from most voters.

The Anywhere-Somewhere divide also deeply influences how dangerously hostile to effective feedback media culture has become and what an alienating structure government (and other) bureaucracies now are. We have Anywhere media and Anywhere bureaucracies that have become deeply dysfunctional and deeply arrogant, and dysfunctional because of their arrogance.

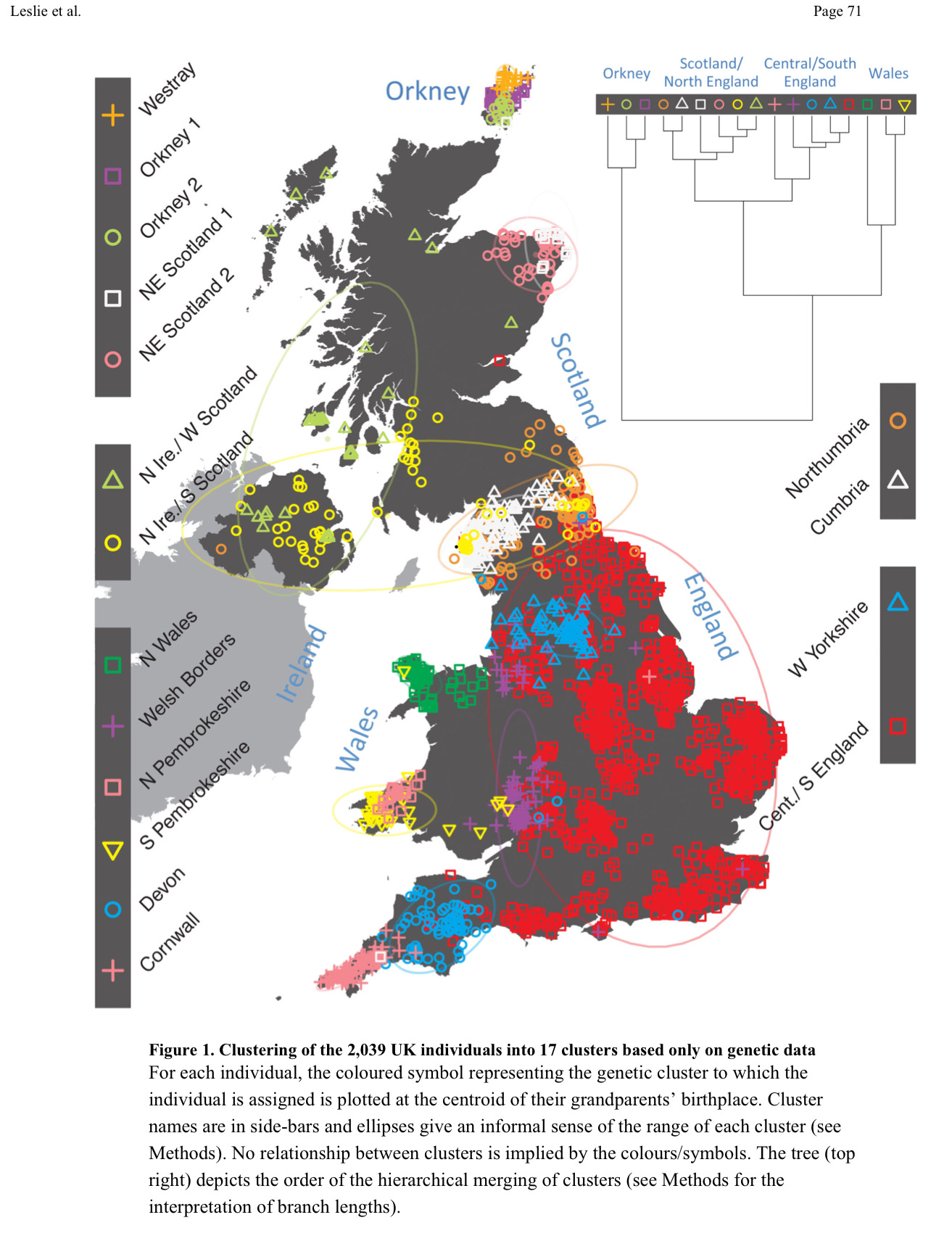

Because Somewhere inhabit localities and create dense networks of local connections, including marriages—genetics has been revealing how remarkably stable European populations have been over long periods of time—ethnicities arise out of Somewheres. These ethnic identities are ruled, suppressed, manipulated, or exulted by Anywhere elites, as convenient.

Nowadays, the default Anywhere response to Somewhere identities and concerns has become derision and suppression. Including the silly lie that ethnicities are somehow modern creations. Certain sorts of mass politics are modern creations, but that is a different matter.

The most dramatic manifestation of the Anywhere-Somewhere split in UK politics is the way the political class has lied to, and misled, British voters to produce a deeply dysfunctional and destructive migration regime that has never had popular support. This has been worsened by the civil service becoming openly resistant to having effective border control.

Comparing the UK to New Zealand, Canada and Australia, the loss of capacity by the British state has become quite marked. In large part, this is the result of 40 years of membership in the EU, where the transfer of functions to Brussels atrophied the UK civil service. It was one of the more powerful reasons why I agreed with Brexit.

But much of the civil service has become Anywhere-arrogant. It clearly has no intention of facilitating policies it does not agree with, and the development of trends in Universities has generated a worship of Theory that generates moral entitlement to so resist. This is another part of the technocratic delusion: no, the UK civil service in particular is no longer a reliable policy instrument.

The effect on the wider electorate is, of course, deeply alienating. They can see their society becoming less functional while an Anywhere-arrogant civil service disconnects what they vote for from what they get and an Anywhere-arrogant media suppresses and derides Somewhere concerns while elevating Anywhere ones.

Creeping credentialism

The spread of University credentialism—which advantages Theory over practical skills—is a large part of what is going on. So we get journalists trained in Theory, rather than their craft, and trained to think of themselves as some moral and epistemic elite compared to voters. We get teachers trained in Theory, rather than their craft, and trained to think of themselves as some moral and epistemic elite compared to parents. We get nurses trained in theory, rather than their craft, so find the bed-pan reality of nursing confronting. And so on.

Even worse, we get folk trained in Theory for pseudo-disciplines where there is no underlying craft, so are only any good at manipulating organisations to push toxic ideas, whose advantage is they have motivational and coordinating power. Hence the non-electoral politics of institutional capture.

Metastasising bureaucracy

A significant part of what is going on is simply metastasising bureaucracy. In the C19th, Western societies adopted the Chinese notion of entry to bureaucracy by examination, to produce meritocratic bureaucracies. It was a response to both the increasing scale of modern life and the increased capacity to measure things, replacing the previous mechanisms of patronage and purchase.

For a while, this worked in the way that early dynastic rule has worked across Chinese history. Western states had effective, largely non-corrupt, bureaucracies that could and did do a reasonable job of carrying out the policies of elected governments.

The trouble is, Western states adopted this Chinese technique without examining Chinese patterns. Chinese dynasties decay, their rule decays, and a large part of this systematic pattern of dynastic decay is that bureaucracy decays in certain ways. That is to say, bureaucracy has certain inherent pathologies that tend to get worse over time.

One is relatively straightforward. Meritocratic selection-by-examination selects for capacity, not character. Over time, it selects more and more for manipulative personalities, who undermine the (prosocial) normative coherence of the organisation and shift it more towards serving the interests of such personalities. With suitable levels of moralising and rationalising of such shifts.

This is related to SciFi writer Jerry Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy:

Pournelle's Iron Law of Bureaucracy states that in any bureaucratic organization there will be two kinds of people:

First, there will be those who are devoted to the goals of the organization. Examples are dedicated classroom teachers in an educational bureaucracy, many of the engineers and launch technicians and scientists at NASA, even some agricultural scientists and advisors in the former Soviet Union collective farming administration.

Secondly, there will be those dedicated to the organization itself. Examples are many of the administrators in the education system, many professors of education, many teachers union officials, much of the NASA headquarters staff, etc.

The Iron Law states that in every case the second group will gain and keep control of the organization. It will write the rules, and control promotions within the organization.

It is, of course, difficult to select for character. That was a major function of duelling: to provide a test of character.1

The useful comparison here is between commerce (business) and command (bureaucracy). Commerce seeks to identify opportunities, assemble and manage resources, deal with risk. Selection is generally for what aligns information and incentives most effectively.

Commerce tends to select against inefficiency, as releasing unused or under-used resources is a profit opportunity. The industrial revolution was not kicked off by academics, or even gentleman-scholars. It was kicked off by jobbing artisans trying to solve technical problems with commercial implications in an institutional environment that allowed that to happen in a cumulative and accelerating way.

One of the larger problems commerce has is dealing with the problems of bureaucracy within firms. Hence the tendency to separate management and control and the rise and fall of corporations—corporate bureaucracies can become highly dysfunctional. They are, however, subject to the pressures of loss and bankruptcy, as well as the market for managerial control—i.e., corporate take-overs.

Notionally, command (bureaucracy) also seeks to identify opportunities, assemble and manage resources, deal with risk. The politicians operate as agents of the voters to provide direction and control, the public service provides the management. Unfortunately, the information and incentive structures are nowhere near as well-structured as those of commerce.

First, the selection pressures within bureaucracy is for more inefficiency, not less, as the more resources are controlled by, and consumed by, the bureaucracy, the better for the bureaucrats. There is also selection for suppressing information, in order to maximise the authority of the bureaucracy: both by elevating what the bureaucracy says and blocking inconvenient information.

There is selection for judging by intention—as that is easy—not actual outcomes. Indeed, much of the cost of bureaucracy is hidden: all the time and effort people have to put in to respond to it, the things that don’t happen because of it. While some of the latter might be good, there is no inherent, systematic feedback either way, so such costs tend to mount over time.

As for risk management, risks are often pushed onto others. Both by consumption of time and effort by others but also because the taxpayer effectively funds and guarantees everything, while feedback about effects is inherently weak and the interest of the bureaucracy is to make it weaker. Bureaucratic self-regulation is not a reliable brake on its incentives for inefficient expansion. Hence much regulation turns out to be more costly than beneficial.

The tendency is for all of this to get worse over time. States are subject to much weaker, and yet more catastrophic, selection pressures than corporations.

Hence you end up with a situation where, for example, a third or more of public schooling employment budgets are taken up by folk who never see a student. This despite there being no significant economies of scale in education, so little for such administrative staff to usefully do.

If a sufficient ax was taken to these ever-increasing bureaucratic overhangs, we could pay teachers considerably more and cut way back on how much of their time is wasted by bureaucratic make-work. Alas, briefly-in-office Ministers for Education have little incentive to engage in such blood-letting: especially when the bureaucracy parades themselves as the Minister’s agents.

All of this is made worse in the current environment, as much of the mainstream media is about blocking feedback, not providing effective versions thereof. A mainstream media that so conspicuously does not identify with most voters, but is in the business of pushing narratives that “establish” those who follow them as being “the (superior) smart good folk”, undermines the feedback that open elections are supposed to provide. Especially when politicians (and especially their staffers) respond to such media framings because they live in media-obsessed information-bubbles and often lack the life experience or social networks that would enable them to break out of said bubbles.

Consuming resilience

I can see how the “forever wars” and the scale of the US national security state led to the development of the notion of the “deep state”. But the term mystifies more than it reveals.

What is corroding the functionality and resilience of democratic states is something that has a long history of doing so—metastasising bureaucracy. Yes, it is made worse by the toxic arrogances of Theory feeding into Anywhere arrogance, both in the bureaucracy and the media. Nevertheless, the alienated frustration of the 2024 UK general election provides an unusually vivid manifestation of the consequences of such dysfunctional, alienating decay of social and institutional resilience.

References

Douglas Allen, The Institutional Revolution: Measurement and the Economic Emergence of the Modern World, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Eugene F. Fama and Michael C. Jensen, ‘Separation of Ownership and Control,’ Journal of Law and Economics, Vol.26, No.2, Corporations and Private Property: A Conference Sponsored by the Hoover Institution (Jun., 1983), 301-325.

Eugene F. Fama and Michael C. Jensen, ‘Agency Problems and Residual Claims,’ Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 26, No. 2, Corporations and Private Property: A Conference Sponsored by the Hoover Institution (Jun., 1983), 327-349.

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989], 1994.

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Timur Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lives: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification, Harvard University Press, [1995] 1997.

Stephen Leslie, Bruce Winney, Garrett Hellenthal, Dan Davison, Abdelhamid Boumertit, Tammy Day, Katarzyna Hutnik, Ellen C Royrvik, Barry Cunliffe, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, Daniel J Lawson, Daniel Falush, Colin Freeman, Matti Pirinen, Simon Myers, Mark Robinson, Peter Donnelly, and Walter Bodmer, ‘The fine scale genetic structure of the British population,’ Nature, 2015 March 19; 519(7543): 309–314.

Robert Jay Lipton, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China, Norton, [1961] 2022.

Robert Jay Lipton, Losing Reality: On Cults, Cultism and the Mindset of Political and Religious Zealotry, The New Press, 2019.

Andrew M. Lobaczewski, Political Ponerology: A Science on the Nature of Evil Adjusted for Political Purposes, Red Pill Press, [2006] 2012.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Benoit Mandelbrot with Richard L. Hudson, The (Mis)behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin and Reward, Profile, [2004] 2008.

Friedrich Meinecke, The German Catastrophe: Reflections and Recollections, (trans.) Sidney B. Fay, Beacon Press, [1946, 1950] 1963.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

The linked paper by Douglas Allen and Clyde G. Reed uses the awkward econ-speak of unobservable social capital. Character is the point.

Just to throw in my shorthand version of this. You don’t need a conspiracy theory ‘Deep State’ when the system has created a self replicating bureaucracy machine. If it follows the rules it has set itself, and it must, then it is inevitable that it will continue to grow and metastasise.

Changing the personnel won’t make any difference, we need to change the algorithm governing the machine.

People love the phrase "deep state" because it implies that there is a locus of control, and to kill the thing they simply need to find and execute that cabal. That all of this happens because of mundane human behavior gives their anger and frustration no target.