Social crowding drives taking up farming, creating states and imperial collapse

Hell is other people, but so are opportunities.

Ever since we became the apex predators — and you are an apex predator when you eat other predators — the main threat to members of the genus Homo have been other members of genus Homo. There is a long history of populations of Homo completely replacing other populations of Homo, and it is not likely that this was ever an entirely peaceful process.

We Homo sapiens are the least reactively aggressive of the primates — so least likely to respond to some action by violence. We are equal with Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) in having the highest level among primates in proactive aggression — our likelihood to plan violence. Homo sapiens are the most gracile of the genus Homo, which suggests that we are the least reactively aggressive version of the genus Homo — we have less need for robust facial protection and more need to express emotion.

It is very likely we are the most gracile (and least reactively aggressive) version of Homo because beta males cooperated to systematically kill the alpha males. In other words — given that reactive and proactive aggression use different brain circuits — we got into a pattern where our high proactive aggression systematically selected for our strikingly low reactive aggression.

Being very good at cooperating — including cooperating to commit acts of violence — would lead us Homo sapiens to be the last version of genus Homo left standing twice over. Being better at cooperating means more effective subsistence and reproductive strategies — so better at competing with rival versions of Homo in extracting food and raising children — and better at wiping rival versions out.

Out-populating and out-warring rival versions of Homo would lead to us being sole surviving version. Indeed, the combination would create a doom-loop for rival versions of genus Homo.

Which raises questions about why it took so long for Homo sapiens to break out of the African bottleneck. Once we did, we spread around the planet pretty quickly.

Indeed, being a migrated-out-of-Africa population was a major advantage, as outside Africa we were vermin — an introduced species without local co-evolved predators, pathogens, parasites or other competitors. Sub-Saharan Africa historically had strikingly lower population density than did Europe and Asia. Only recently has it broken out of its predators-pathogens-parasites-mega-herbivores constraints on the human population.1

Transitioning to farming

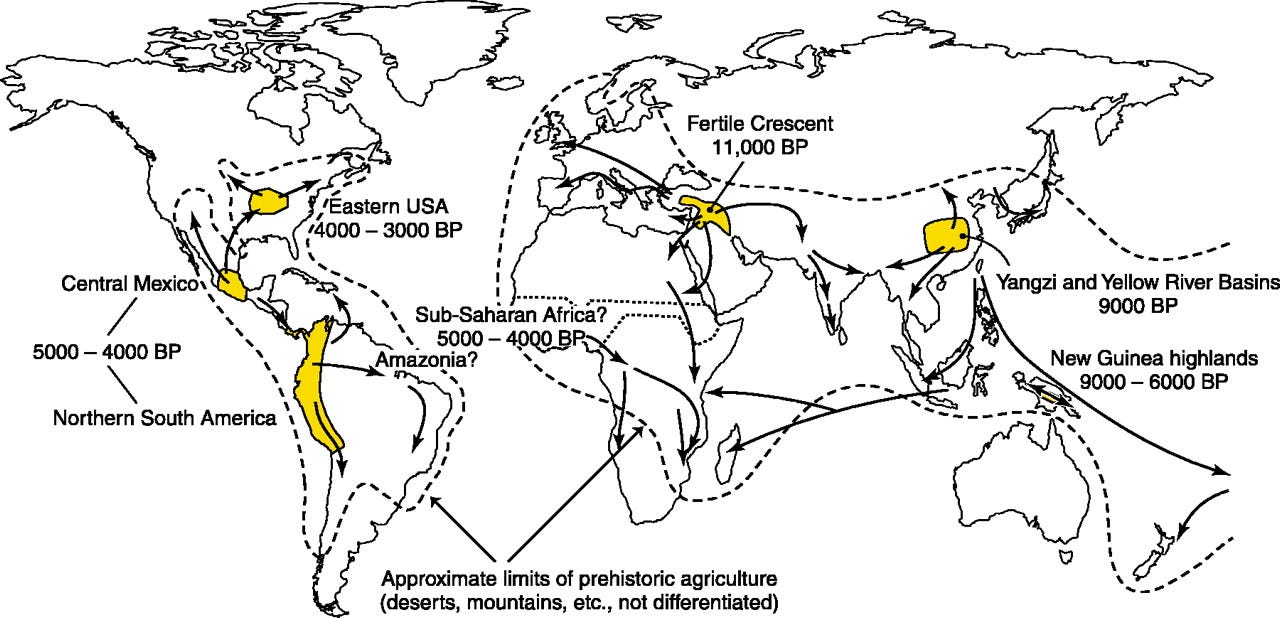

Foraging populations were denser where resources were more plentiful. With the stabilisation of warmer weather in the Holocene, farming developed in dense-food-resources environments (typically in or around river valleys) across the planet.

As there is no sign in the archaeological record of food pressure in the farming-origin areas, the hypothesis of Danish economist Ester Boserup that a lack of alternative food sources led to the adoption of farming is not supported by the evidence. Yet, farming developed again and again around the globe, always in resource-dense — so relatively high population-density — regions.

As the archaeological record is very clear that farming always predates cities, the thesis of economist Jane Jacobs that urbanism lead to farming is also not supported by the evidence. Foraging, even in resource-rich areas, just does not enable the population density required to have anything beyond a (large) village.

Farming sometimes follows, and sometimes precedes, sedentary living. So, sometimes sedentary populations develop farming and sometimes mobile populations do.2

Once populations take up farming, some level of sedentism almost invariably follows. As sedentary living — that is separate dwellings — creates households, sometimes becoming households precedes farming and sometimes it follows it.

In order to take up farming as a dominant subsistence strategy, foragers have to change their attitudes to both time (becoming much more patient) and space (accepting property in land). They also need access to plants that are sufficiently controllable, and sufficiently calorie-dense, to sustain farming. That is to say, plants that are sufficiently domesticated to become crops.

All these processes take time. It is quite clear that the transition from foraging to farming takes centuries.

Social crowding

So, to shift from foraging to farming requires some continuous, generation-after-generation, pressure that operates in resource-dense localities. That pressure, I suggest, is social crowding.

The more crowded a locality, the more likely are encounters with outsiders, so the riskier it is for women and children to forage near the boundaries of their group’s territory. An obvious response is to invest in subsistence that minimises the need to travel to said borders.

Creating denser patches of grains and other edible plants — either around the residences or in the centre of one’s territory — would reduce the need to travel to forage. Over time, selection would lead to more productive plants. This would enable more investment in raising such plants. This would lead to less travelling to forage, but also more access to calories.

The more one relies on such plants, the more investment in skills would shift from foraging to plant-management (farming). This, along with less travelling to forage, would make it easier to raise kids, reducing the need to space one’s births. In other words, less killing or abandoning of one’s own children.

The increase in available food — both from plants becoming more productive and more planting — would enable the consequent increase in fertility. This would increase the social crowding, further increasing all the above effects. Eventually, the population would reach a level such that farming becomes the only way one could sustain your population.3

Farming thus reduces the resource/skill/land area size of human niches and increases the number of such niches. This leads to the population pressure that saw farming populations replacing foraging populations across arable land.

This process of farmers and farming replacing foragers and foraging has been going on for millennia. The last continent it reached was Australia, just over two centuries ago. In parts of Africa, the Americas, and Asia, the process is still going on.

Social crowding thus provides the generation-after-generation pressure that leads to the shift from foraging to farming, even though farming diets were something of a metabolic disaster: a case of our cultural evolution outpacing our biological adaptations. Farming niches that were smaller — so increasing fertility — and more numerous — so further increasing sustainable fertility — won out over larger, and scarcer, foraging niches.

The state response

Social crowding would also lead to other changes. Notably, more trade and more use of ritual networks to sustain peace and cooperation.4 That constructed ritual centres first arise during the transition to farming also fits into social crowding driving the transition to farming. When cities evolve, they are almost always also ritual centres, due to the importance of ritual as a mechanism for social integration and coordination.

As social crowding continues to rise, that leads to more issues in managing coordination goods. Coordination goods are goods such as:

club goods (e.g. group-membership, including ritual societies) where folk can be excluded, but can jointly consume the good;5

common-pool resources (such as feast, fisheries and irrigation systems) where folk cannot be easily excluded, but one’s use of the good precludes another doing so; and

public goods (such as group defence) where folk cannot be easily excluded but can jointly consume the good.

As localities develop various ways of managing such coordination goods, there are created both the pressures — and resulting social structures — that lead to chiefdoms and states. Chiefdoms and states are ways of managing — or creating the social peace that enables — coordination goods, increasing the scale and scope of both.

As a result, state societies systematically have more complexity and capacity than non-state societies. Indeed, a regular consequence of stable imperial rule is significant population growth. This success can have a de-stabilising impact over the long-term, as it can lead to some combination of shrinking farming niches (making taxes increasingly onerous),6 a growing landless underclass (creating an expanding bandit/outlaw problem) and a growing elite (creating increased competition for elite niches).

Polygyny tends to aggravate the latter two problems. For polygyny transfers women up the social scale — creating a no-marriage-prospects, non-breeding, so highly disruptive, male underclass — and increases the number of sons of elite males competing for proportionately fewer-and-fewer elite positions.

These patterns alone are enough to create the Chinese dynastic cycle, which is a particular example of the instability of land-empires. A cycle that operates in a geographically-bounded — hence regularly (re)uniting — civilisation.

Intensified competition for elite positions tends to favour more manipulative personalities. Given that meritocracy selects for capacity but not character, the latter effect magnifies the aforementioned corrosive patterns, as manipulative, morally-disordered personalities are increasingly selected for within the state apparat.

In other words, social crowding also explains patterns of imperial collapse.

States as emergent responses to social crowding

The circumscription model of the origins of states is essentially a localities-with-social-crowding model, where there are systematic reasons that a critical mass of people do not respond to the problems by moving (exit) but evolve local responses (voice). The original model focuses on warfare, but a broader conception of social responses to crowding and coordination issues appears to be more compatible with the evidence.

In particular, irrigation is strongly associated with the origin of states. Irrigation is a common-pool resource that increases the value of land as an asset, so driving up the demand for protection, while its management generates the sort of social complexity from which chiefdoms and states can arise.

There are two possible strategies in creating states: dominance or association. The dominance strategy arises when an elite able to marry together protection and predation — usually with some hereditary ruler at the apex — comes to dominate a territory.

The associational strategy is when folk jointly create a responsive central authority. All the non-autocratic city-states represent the associational strategy. We see this strategy in classical Northern India, with the gana-sangha or gana-rajya states; in Mesoamerica (e.g. the Tlahtōlōyān Tlaxcallan, the Confederacy of Tlaxcala); and in the Classical Mediterranean.

Without a capacity to scale-up representation, the associational strategy is limited to city-states, or other highly localised polities. Autocracy has far less problems in operating at scale. The scale advantage of autocracy sees associational states being overwhelmed by dominance states in all the above regions.7

The Roman Republic shifted from an associational state to a dominance state, though the Principate’s reliance on self-governing cities retained strong associational elements in its administration. That is, until the collapse in Roman silver production meant shifting from a money-tax state, with a very lean administration, to an taxation-in-kind state, requiring a massive increase in the imperial bureaucracy. As this expanded bureaucracy was imperial in all senses, it undermined and largely replaced city self-government, so the late Roman imperial state adopted the full dominance model.8

Medieval Christendom’s development of the representative principle enabled it to generate Parliamentary states at scale, which leads to a revival of the associational strategy. It also led to much more institutional variety in Europe, giving the selection processes of history more to work on, leading to the evolution of unusually effective and capable states.9

Paths to states

Given the variation in local geographies, crops and cultures, it is unlikely there is a single path to the creation of states, whether for the dominance or the associational strategies.

Conquest warfare is rare in independent communities, somewhat more common in chiefdoms and far more common with states. So, conquest warfare seems more often a consequence, than a cause, of the development of states.

Similarly, significant social differentiation generally comes after states. This is because states hugely increase the creation and extraction of surplus, so class differentiation.

On the other hand, coordination goods arise before states, including public goods provision.

Before states, there are chiefdoms. Which raises the question: what do chiefs do?

Africa still has chiefs, and we can observe what they do. They arbitrate disputes that cannot be dealt with by other mechanisms, so risk spiralling out of control.10 They coordinate, particularly local defence. They redistribute, organising the swapping of products and smoothing out seasonal and annual variation. It is typical for folk to be socially ranked relative to the chief.

These functions are about managing the risks and benefits of social crowding. Chiefdoms can grow, so manage social crowding at increased scale, by having sub-chiefs.

If there are powerful ritual societies, the chiefs can be effectively instruments of the ritual societies. Ritual societies seem to be the mechanism by which charismatic shaman are replaced by trained priests.

As both associational states and dominance states have priesthoods, they do not seem to be the key differentiation for whether chiefdoms develop into associational or dominance states.

The key differentiation appears to be in how mobilisation of local warriors develops. In dominance states, they become agents of the ruler. In associational states, they collectively become the decision-makers.

The Greek polis was very much based on citizenship as grounded in fighting for one’s polis. Democracies were typically naval powers, as they gave the demos — who provided the rowers for the war galleys — the vote.

The gana-sangha or gana-rajya states of India are sometimes referred to as Kshatriya republics, because their ruling assemblies were made up of Kshatriya. In Mesoamerica, warriors dominated the ruling council of the Tlahtōlōyān Tlaxcallan.

While we later see commercial republics such as Carthage, Genoa, Venice, Novgorod, the early associational states seem to be all essentially warrior-polities. This makes sense, as the state represents coercive power and which state-building strategy is adopted (associational or dominance) is about how coercive power is applied and by whom.

States and taxes

There cannot be a state without a tax base. While trade was a very important revenue source regarding the scale of states,11 land was the dominant income source for early states: whether by taxing of goods in kind or labour service.

To have effective labour service — especially at any scale — requires stored food. To be able to support a state apparat of any scale requires stored food. This means seasonal crops (grains or potatoes). Seasonal crops both increase the protection problem and provide a tax base.

ALL the early states arose in places with seasonal crops. New Guinea, despite having millennia of horticulture and warfare in circumscribed valleys, never developed either states or chiefdoms. New Guinea had no seasonal crops, so no tax base: not even to support chiefdoms.

At the other end of the imperial scale, labour-service autocracies — such as pharaonic Egypt and the Khmer Empire — tended strongly towards monumental constructions, as labour service has a “use it or lose it” quality. By mobilising labour service each and every year, the authority of the ruler is routinised.

Monumental constructions direct such routinised dominance into enduring monuments of the ruler’s authority. Both pharaonic Egypt and the Khmer Empire elevated their rulers to divine status, supported by localised rituals and ritual centres, radiating out from those centred on the ruler, while using temples as centres of administration. (An excellent podcast on the rise and fall of the Khmer Empire is here.)

Responses to social crowding

So, social crowding leads to the development of farming. In places with seasonal crops — so stored food — social crowding leads to the rise of chiefdoms and then states. If the arbitrating/coordinating/resource managing role of the chief becomes based on control of a warrior elite, an autocratic dominance state develops. If those roles become dispersed among the warriors, then an associational state develops.

Without the representative principle, associational states cannot operate at scale. Autocracies can operate at scale, so autocracies win out over time over associational states. As empires arise, the social peace they impose increases trade and population.

As the population increases within an empire, more social crowding effects arise: including more marginal farming niches, more socially-excluded bandits and outlaws and more intense elite competition. The last tends to encourage more selection for manipulative (i.e., morally disordered) personalities. A sufficient combination of such factors generates imperial collapse.

Commercial republics are generally a later development. Europe’s development of the representative principle allowed the associational strategy to be scaled up. The economic growth and discovery benefits of commerce, operating in and across competitive jurisdictions, eventually created the modern take-off to mass prosperity: including the recent mass shifts out of poverty.12

References

Books

Catherine M. Cameron, Captives: How Stolen People Changed the World, University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Bryan Hayden, The Power of Ritual in Prehistory: Secret Societies and the Origins of Social Complexity, Cambridge University Press, [2018] 2020.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Jane Jacobs, The Economy of Cities, Vintage Books, [1969] 1970.

Robert L. Kelly, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum, Cambridge University Press, [1995] 2013.

Mancur Olson, Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships, Basic Books, 2000.

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, [1990] 2011.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Emmanuel Todd, The Lineages of Modernity: A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus, (trans. Andrew Brown), Polity Press, [2017] 2019.

Peter Turchin, War and Peace and War: The Life Cycles of Imperial Nations, Pi Press, 2006.

Articles, papers, book chapters

Samuel Bowles, ‘Cultivation of cereals by the first farmers was not more productive than foraging,’ PNAS, March 22, 2011, vol. 108, no. 12, 4760–4765.

Gregory Clark, ‘The interest rate in the very long run: institutions, preferences and modern growth,’ Working Paper, May 2005.

Jared Diamond, ‘The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,’ Discover Magazine, May 1987, Pages 64-66.

Jared Diamond and Peter Bellwood, ‘Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions,’ Science, Vol. 300, 25 April 2003, 597-603.

Manuel Eisner, ‘From Swords to Words: Does Macro-Level Change in Self-Control Predict Long-Term Variation in Levels of Homicide?,’ Crime and Justice, 2014 43: 65-134.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77.

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021).

Katherine J. Latham, ‘Human Health and the Neolithic Revolution: an Overview of Impacts of the Agricultural Transition on Oral Health, Epidemiology, and the Human Body,’ Nebraska Anthropologist, 2013, 187, 95-102.

Carlton Martz, ‘Tlaxcalan: The Indigenous Democracy of Mexico,’ BRIA, 37:4 (Summer 2022), 1-5.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144.

Anna Revedin et al, ‘Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing,’ PNAS, November 2, 2010, vol. 107, no. 44, 18815-18819.

David Schonholzer, Pieter Francois, ‘Environmental Circumscription and the Origins of the State,’ July 29, 2023.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021).

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Michael E. Smith, Jason Ur, and Gary M. Feinman, ‘Jane Jacobs’ ‘Cities First’ Model and Archaeological Reality,’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (4) 2014 (April 17): 1525–1535.

Peter Turchin, ‘A theory for formation of large empires,’ Journal of Global History, (2009), 4(2), 191-217.

Lizzie Wade, ‘It wasn't just Greece: Archaeologists find early democratic societies in the Americas.’ Science, Mar. 15, 2017.

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS, January 9, 2018, Vol.115, No.2, 245–253.

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9, 2077.

Julia Zinkina, Andrey Korotayev, and Alexey Andreev. ‘Circumscription Theory of the Origins of the State: A Cross-Cultural Re-analysis.’ Cliodynamics, 7, 2016: 187203.

This historically low population density is why Africa was the slave continent (and the Americas became — after being devastated by the Eurasian disease pool — the imported slave continents). With low population density, scarce labour was perennially more valuable than plentiful land. This leads to human bondage, as exploiting labour generated a better return than landholding. Slavery — rather than serfdom — is used when labour has to be imported, as moving humans at will requires a more intense level of domination. Sub-Saharan states were overwhelmingly slave states.

The Atlantic slave trade — as horrible as it was — was a relative latecomer to slavery in Africa. The centuries older Saharan passage was as horrible as the Atlantic passage. The Islamic slave trade lasted far longer than the Atlantic slave trade, with the added feature of systematic castration of male slaves. Hence — along with the incorporation of the children of Muslim fathers in the Muslim community — the lack of a slave-ancestry diaspora in the Islamic world. Conversely, the Arabic slang for a Sub-Saharan African is still abd, slave or creature (Abdullah = slave/creature of God).

There is evidence of processing of wild grains from 30,000 years ago.

As domestication of food animals is significantly later than that of plants, hunting continued, maintaining the pressure to reduce the foraging mobility of women and children.

Between trade, ritual gatherings, plunder and captives, there was considerable capacity for transfers of different strains, and so the the development of grain hybrids, over the course of the centuries of transition.

Residence in a country is a club good: hence the disputes over border control.

The shrinking of farming niches can be a peripheral phenomena from population pressure leading to the use of land of decreasing productive value; it can come from increasing division of existing landholdings; from environmental degradation of core areas; or from shifts in climate reducing the productivity of land or creating destabilising variability in climatic conditions.

High levels of predation intensifies demand for protection: Mancur Olson’s “stationary bandit” analysis works both ways. High levels of return from predation-and-protection also creates more intense levels of competition to capture those returns:

Despite the small population [of rulers] of just above 1,600 individuals (among whom fewer than one homicide would be expected in contemporary society), the data set has enough statistical power to examine overall trends over time. The reason is that over the entire period, 218 of all rulers were murdered, corresponding to 14 percent of the sample. Calculated as a homicide rate per ruler-year, the risk of being killed amounts to 1,003 per 100,000, making “monarch” the most dangerous occupation known in criminological research … (Eisner, 2014)

The dominance model comes in two versions. The fiscal state, which relies on monetary taxes, and the extractive state, which relies on taxation in kind, including labour service.

The competitive jurisdictions of Europe, with their elevated social bargaining, enabled the development of unusually vibrant commerce, which eventually created the Great Enrichment aka the Industrial Revolution.

If people cannot avoid each other, and the consequences of ignoring a transgression are too high, then private governance/dispute-resolution mechanisms are not likely to be effective.

Including by increasing production via greater specialisation in use of land.

Lorenzo giving insight into why we are the way we are yet again.

Thanks for writing.

"the archaeological record is very clear that farming always predates cities,"

Except for Gobekli Tepe (and maybe Çatalhöyük) where it seems like the city was started before agriculture. But those places seem to be the exceptions that prove the rule as well as having been one-offs and not to have contributed anything to the rest of human history as far as we can tell