Crook and flail

Rulership as a dance of protection and predation.

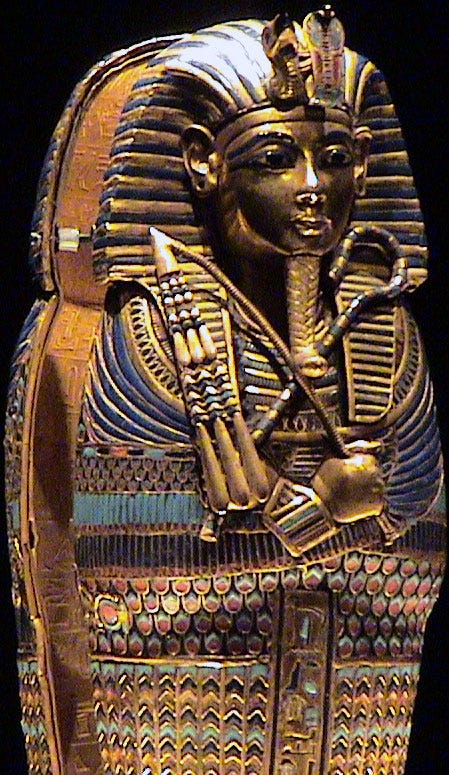

The crook and flail were symbols of the deity Osiris that became symbols of pharaonic authority. They symbolised Pharaoh as protector of his people and the fertility of the land. The crook was a form of sceptre or staff, which has a long history as a symbol of royal or imperial authority.

These are symbols of authority, but they are not weapons, nor implied as such. This is ruler as protector and guide.

Ceremonial maces have been used as symbols of authority. But the more they have been used as symbols of authority, the more ornate, and obviously ceremonial, they have become.

Maces were the first weapons specifically designed to kill other humans. Yet they have less specific association with rulership, with royal or imperial authority, than the staff or sceptre.

There was always a predatory aspect to rulership, but rulership is never just predatory. It also has a protective role. Indeed, the protective role both legitimates, and provides cover, for the predatory role precisely because it is a genuine role.

Order versus chaos

Farming societies, particularly those reliant on seasonal crops — so food stored across seasons: notably grains and potatoes — need a certain level of social order to reliably eat. Periods of serious strife and disorder could be so horrific, that the simple achievement of a stable social order was regarded as being of the highest priority.

The lack of social pacification is universally lamented in such societies. Such as a prayer averting Viking raids:

Summa pia gratia nostra conservando corpora et cutodita, de gente fera Normannica nos libera, quae nostra vastat, Deus, regna.

(Our supreme and holy Grace, protecting us and ours, deliver us, God, from the savage race of Northmen which lays waste our realms.)

The famous lament on the civil strife in England between Stephen (r.1135-1154) and Matilda in The Laud (Peterborough) Chronicle, annal for 1137, is of a similar vein:

⁊ hi sæden openlice ðæt Crist slep. ⁊ his halechen.

(And men said openly that Christ and His saints slept)

Long before the Zoroastrian notion of the universe as a contestation between good and evil gained currency, farming societies — particularly complex farming societies — saw the world as a contestation between the forces of order and the forces of chaos.

Chinese political thought was an evolving interaction between Legalist and Confucian notions of proper social order. Brahmin thought and practice produced a highly mythic and hierarchical notion of order.

Pre-Christian Rome was very much a society concerned with achieving social order. The Roman lack of concern with the monotheist good-versus-evil dichotomy is why this highly ordered society — which created the first great legal order — can seem wildly amoral (or worse) to us.

In pharaonic Egypt, this order-versus-chaos perspective was expressed as the contestation between

Ma’at: truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, justice,

and

Isfet: injustice, chaos, violence; doing evil.

Pharaoh, as the shepherd of his people, was the embodiment of order. Pharaoh was the link between the godly order of the divine and the worldly order of Egyptian society. A society that lived in and from the thin green land of the black earth watered by the life-giving Nile’s annual flood and bordered by the stark desert.

Not coincidentally, all four civilisations took the ordering role of ritual very seriously, as was common in farming societies.

From farming to states

Early states seem to have arise from various mixtures of coercive and associational processes. They arose in highly productive farming areas, that relied on seasonal crops, with some level of ecological circumscription.

The circumscription model for the origins of states was originally proposed by anthropologist Robert Carnerio. It has been further developed by a recent empirical study of the evidence, using the Seshat database of historical societies.

The fertility of the land was needed to support a population dense enough to sustain a state apparat. Highly fertile land generates the level of social crowding that creates the pressures that lead to creation of states.

The development of farming itself is the necessary first step. But farming does not automatically lead to state creation.

Farming means moving from foraging to farming niches. We Homo sapiens are the niche-creating species. In a sense, the niche-breaking species.

Sedentary living — even if the residents are still foraging — makes supervision of children easier, as having separate households creates neighbourhoods and so increased capacity to economise on child-minding. Children can, to some extent, mind themselves. Though neighbourhoods also generate that endless competitor to parental authority, the peer group.

Farming niches are smaller than foraging niches — with children being able to be more productive quicker — so women can have more children. Less resource-expensive children means less killing of their own babies than is common in foraging societies.

Sedentary foraging and farming both arise in resource-dense environments. That means more social crowding. As social crowding increases, concern over women (with children in tow) foraging widely is likely to increase. The more one relies on deliberately cultivated plants, the less women (and attached children) have to range to get food.

Farming enables the creation of more (potentially many, many more) niches for humans in a given territory than foraging does. Even so, moving from supplementing foraging with cultivated plants to relying mostly on cultivated plants takes many generations.

Selection for more productive versions of cultivated plants has to reach a certain level of calories and nutrition. The changing of attitudes to time (patience) and space (land ownership, households) that the shift from being foragers to being farmers requires also takes generational time.

So, there is increased population density and social crowding, but also increased separation into individual households. Possibly, in part, as a refuge from the social crowding.

Coordination problems

The places where states originally arose had some form of irrigation. Irrigation requires coordination, increases production (so population and resource density), and increases the protection problem.

In such environments, there is creation and management of common-pool resources (such as irrigation systems), club goods (such as feasts) and of public goods (such as defence). What we might call coordination goods.

Club goods can include the networking services of secret/ritual societies. Such societies can be effective mechanisms for social predation, including resource extraction. Chiefdoms — proto-states — can be instruments of, or dominated by, such societies.

Whether such ritual/secret societies scale up to form states, or states arise to suppress such societies, is hard to say. Perhaps the former in some cases, the latter in others. Such ritual societies do seem to be mechanisms for shifting from the charismatic shamans of foraging societies to the trained priests of farming societies.

The early states were all based on farming societies. You needed the density of population and resources to support a state, and the social crowding to generate the demand for, and coordination of, common-pool resources, club and public goods, that lead to states. Stored food (i.e. seasonal crops) were required for the tax base, to support a state apparat, while the protection problem that stored food generated increased the demand for public goods.

The tax basis of early states consisted of the products of farming, labour service, and trade. Even when it came to extensive labour service, stored food was required. Labour service could be a tax-in-kind to the state (corvee labour) or some form of labour bondage (serfdom or slavery).

In the latter case, the extraction of surplus (income above subsistence) did not necessarily require a state — slavery existed in pre-state societies. State enforcement was required, however, if labour bondage was to occur on any scale.

The unwillingness of the Western European crowns to enforce the required landlord cartel was why serfdom did not return to Western Europe after the Black Death: a very unusual pattern in human history. Normally, the result of labour being more valuable than land was some form of labour bondage: serfdom if the population was in situ, slavery if they had to be imported.

Since labour being more valuable than land was perennially the case in Sub-Saharan Africa — for that was where Homo sapiens evolved, so it was full of pathogens, parasites, predators and mega herbivores that co-evolved with humans, keeping human population density down — African states tended to be slave states, with slaves being a major trade and state-revenue item.

Pastoralist polities

Pastoralism, which developed later than farming, could also support extensive polities. But pastoralist polities tended to be more super-chiefdoms than conventional states. Just as shamans remained a feature of such societies much longer than in farming polities.

That the mobile assets (herds) of pastoralist societies required investment in effective, and highly mobile, male warrior teams made them formidable warrior societies. It also made them trickier to manage and harder to extract a surplus from. Hence they tended to be more super-chiefdoms than states.

Moreover, the grasslands could only support a certain number of pastoralist niches. Over-production of sons for the available elite niches by polygynous elites tended to make such polities somewhat unstable, as (destabilising) competition for elite niches tended to increase over time.

Trade and empire

Trade across ecological zones encourages the formation of states, as trade provides a taxable stream of revenue and increases the return from social order. The ecological boundary expanded trade possibilities, as people exchanged the varying products of the different ecological zones. Much of the power of Islam came from its ability to coordinate pastoralists and then redistribute the gains-from-trade to more poorly endowed regions.

The ecological boundary zones between farming and pastoralism tended to produce empires, as it selected for military effective states or dynasties that could also encourage, and tax, trade across the ecological boundary.

The most historically significant such trade being the silk-for-horses exchange that was at the heart of the Eurasian trade system from the time of the First Emperor (r.221-210BC) to the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644). From the C16th onwards, it was replaced by the American-silver-for-Chinese-goods system that lasted until the collapse of the Spanish empire in the Americas and the era of railways and steamships.

Ecological circumscription and surplus

From all this, we can see the role of ecological circumscription in the origin of states. Such circumscription increases the capacity for, and benefit of, social coordination.

Ecological borders mean folk have sufficient commonality to have shared structures to deliver/facilitate coordination goods without trying to coordinate over too large or too ill-defined an area. Moreover, as economist Arnold Kling points out, it makes it more likely that folk will invest in connection (voice) rather than just move (exit).

The key dynamic was social, rather than resource, crowding as coordination goods are a human interaction — far more than an extracting-resources-from-the-world — problem. The notion that it was pressure on resources that drove the development of farming is not supported by the archaeological evidence.

Given that coordination has costs (as well as benefits), resource pressures inhibit coordination unless such coordination readily gives access to more resources than its lack would. Social crowding arose well before resource crowding became a problem.

To have a state, farming niches have to be sustainable after taxes are extracted. That means resources are extracted before they turn into extra babies. This means that states create surplus (income above subsistence): indeed, they dominate the creation and extraction of surplus.

The dance of predation and protection

So, we come to the dance of predation and protection that is at the centre of rulership. The return from social order, from social pacification, can be very high, as state societies generate much greater surpluses than do pre-state societies.

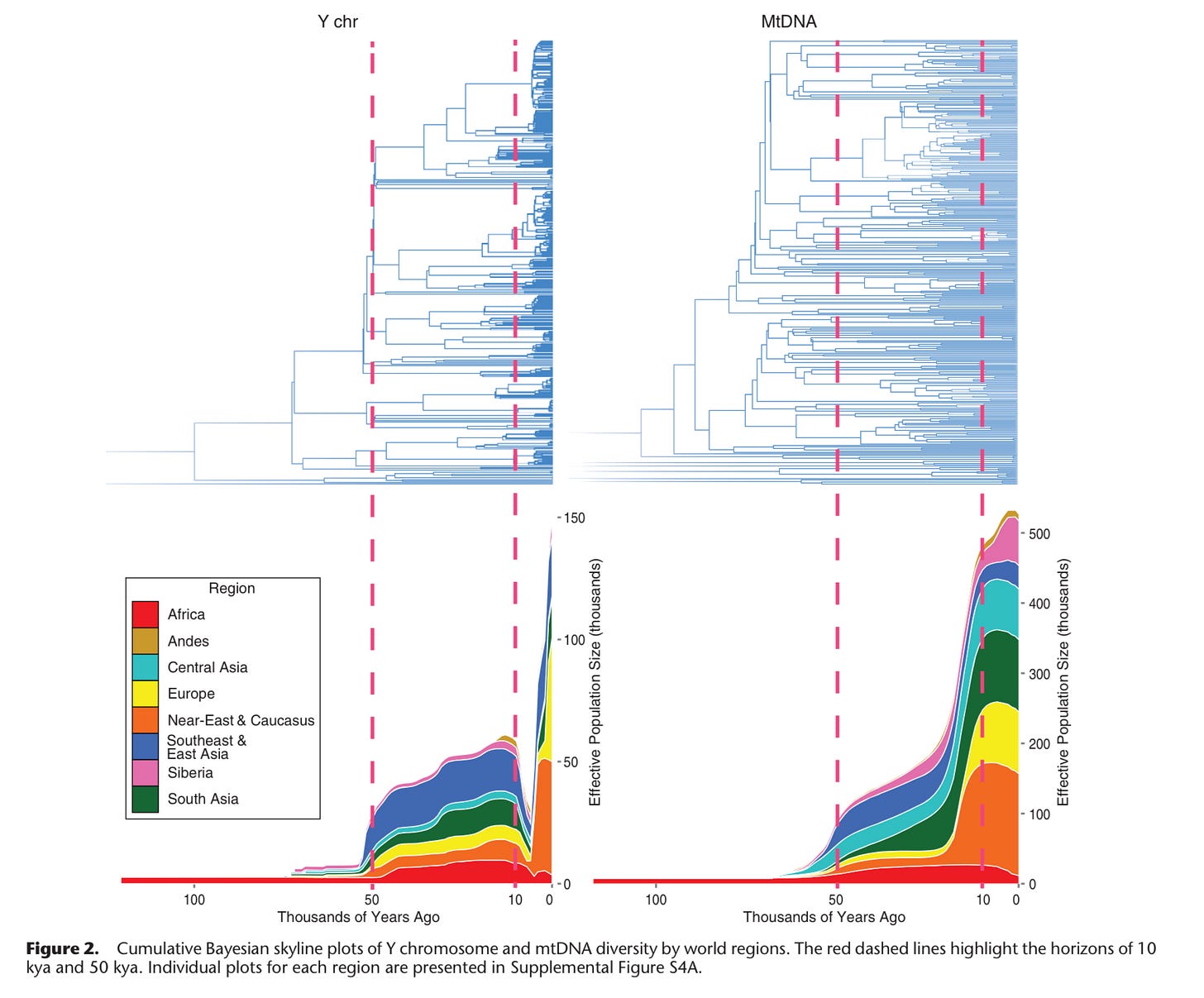

First, there is the straightforward advantage of much less homicide. The harrowing of male lineages, the Neolithic y-chromosome bottleneck, came from the development of farming and pastoralism increasing both population density and assets to be protected (or taken).

The development of clans — particularly patrilineal clans, particularly among pastoralists — increased the social technology of aggression but not the social technology of exploitation. Defeated males would be killed or enslaved and the women appropriated.1

The variation in the degree of the harrowing of male lineages by region suggests that the more strongly the principle of patrilineality was developed, the more intense the harrowing of male lineages, as warriors who grew up together would tend to make more cohesive teams, intensifying the competition and the selection for effective (male) teams.2

The harrowing of male lineages largely comes to an end with the development of chiefdoms, and particularly states. With the development of chiefdoms and states, the social technology of exploitation caught up with the social technology of aggression, as defeated males could be taxed and so become income sources.

In other words, predation-without-protection was replaced by predation-with-protection.

A sign that pastoralist polities were more super-chiefdoms than conventional states is that some harrowing of male lineages continued in the steppes, even after the development of steppe empires.

Pharaoh would be depicted crushing outsiders beneath his chariot wheels, and driving them away, not only to say “I am Pharaoh, fear me” but also “I drive the raiders away”. The shepherd of his people drives the human wolves away. He may even use his dogs to do so.

Rulers would celebrate conquest, not only to show their power, but also because the further the borders were away, the further away were the raiders. Borderlands were dangerous places.

Part of the Ottoman success as conquerors was to regularise Islam’s sanctified aggression against outsiders. Ghazis — holy warriors — would raid non-Muslim borderlands, driving away the population and degrading the productive capacity of said borderlands. At some point, the Ottoman army would move in and conquer the area. Settlers would be brought in from elsewhere in the Empire, and the ghazis would move to the new border: rinse and repeat. This process enabled the Ottoman state to march from inner Anatolia across the Balkans to twice threaten Vienna.

The process was brought to a halt by the Habsburg and Venetian creation of the military frontier: fortified, self-governing villages whose armed inhabitants would raid back. A large reason why medieval Rome and dynastic China ultimately failed against the pastoralists is that their highly bureaucratic state apparats serving command-and-control autocracies would not tolerate the self-armed, self-governing borderers that was the most effective way to hold off the pastoralists.

At the heart of the dance of protection-and-predation is that a protected people in a pacified land could be taxed. This enabled the creation and extraction of astonishing levels of surplus. As the great monumental creations such as the Great Pyramids, Angkor Wat, the Great Wall of China, the Pyramids of the Moon and the Sun, etc., etc. demonstrate.

Whatever other function they served, such monumental constructions operated as rituals of authority, with the labour service that built them being regular, and regularised, manifestations of the ruler’s authority. Or, in more associational states, the power and grandeur of common effort.

Rulers typically allied with the providers of ritual and legitimating services: what political economist Jared Rubin calls propagating agents. Sharia and Brahmin law were constraints only when rulers allied with the ulema (religious scholars) or brahmins. But such alliances could be so useful, that rulers would accept the resulting constraints.

Part of the benefit of law based on revelation to rulers is that it so massively impeded entrenching social bargains in law, it left autocracy as the only operative system of government. In the case of Islam, that led to the adoption of the mamluk (slave warrior) system — warriors separated from any kin networks, so their only local connection was to their master — whose autocratic effects persist to our own day.

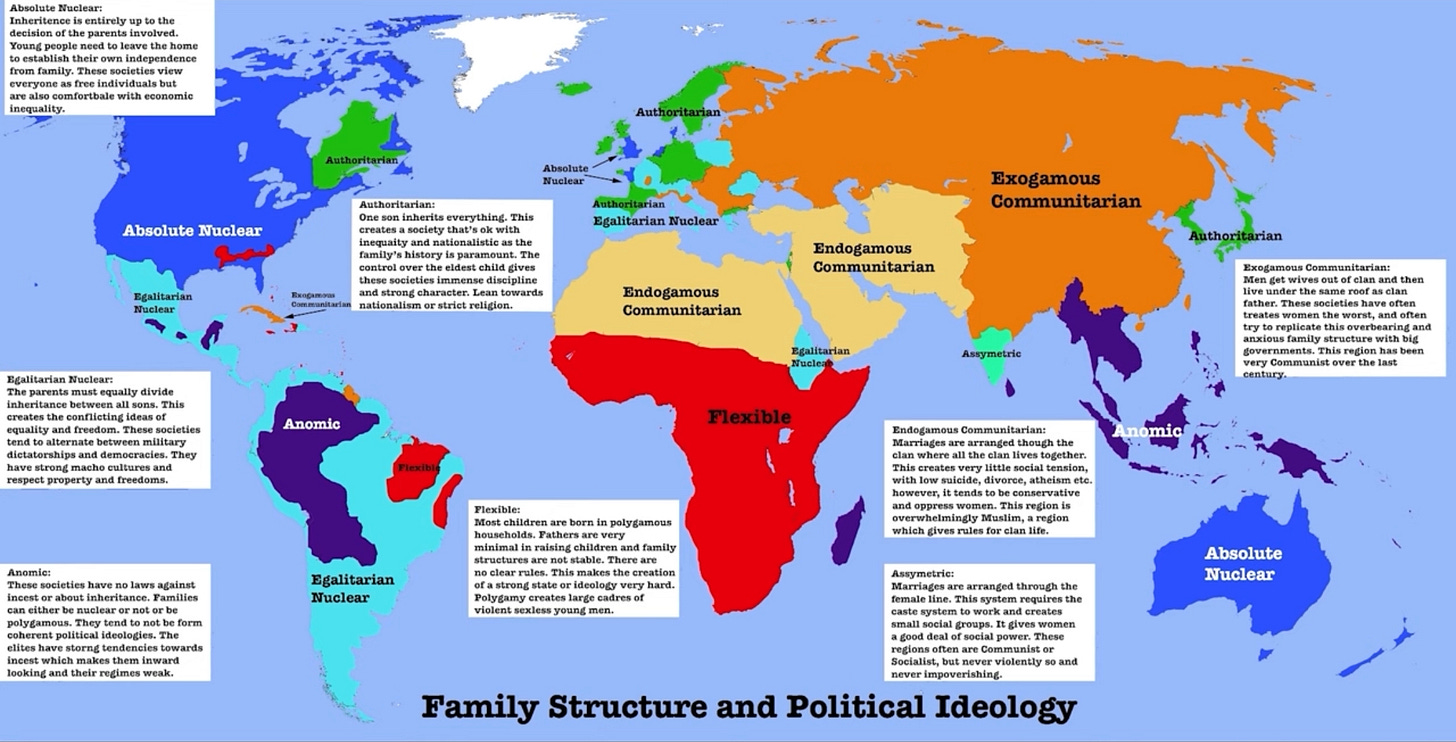

That the mamluk system was a mechanism to evade having one’s instruments of rule colonised by kin groups raises the question of how much of the family and kin-group system — endogamous (cousin-marrying) communitarian families, in anthropologist Emmanuel Todd’s terminology — drives the continuing anti-democratic effects within “conquest” Islam, but not Islam further east or north.

The (under-appreciated) importance of, and social return from, pacification continues to our own day.

The European Age of Exploration led to the creation of network globalisation. The development of steamships and railways, the application of steam engines to transport and so trade, created mass globalisation. Globalisation that led to such a level of integration of markets that we can talk of global prices.

The first age of mass globalisation (1820s - 1914) was based on the Royal Navy’s oceanic hegemony pacifying the world’s oceans. The second age of mass globalisation (1945 - present) has been based on the US Navy’s oceanic hegemony pacifying the world’s oceans. An oceanic hegemony that is even more complete when you add in the US’s allied navies.

Yet the returns of social pacification are so taken for granted, that the role of Anglo-American naval hegemony in enabling mass globalisation continues to be belittled or ignored.

The defund-the-police agitation, and the social destructiveness of “woke” prosecutors, also represent a wilful refusal (at best) to understand the value of social pacification. Societies shielded by oceanic moats may be particularly prone to such views.

Rulership is always a dance of predation and protection. That is what creates the paradox of polities. The words of Muslim polymath, the first and greatest of historical sociologists, ibn Khaldun remains as true now as when he wrote them:

Mutual aggression of people in cities and towns is thus averted by the authorities and by the government, which hold back the masses under their control from attacks and aggression against each other. They are thus prevented by the influence of force and governmental authority from mutual injustice, save such injustice as comes from the ruler himself.

The Muqaddimah, I.2.7.

Were the European nobility a predatory class? Yes. Were they a protective class? Also yes. They couldn’t be the former, as a stable social formation, except by being the latter. But being the latter meant they were also the former.3

Rulership’s dance of protection and predation echoes through history. It has definitely not stopped in our own time.4 The paradox of polities, and its dance of protection and predation, never goes away.

References

Books

Faisal Z. Ahmed, Conquests and Rents: A Political Economy of Dictatorship and Violence in Muslim Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Christopher I. Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, 2009.

Catherine M. Cameron, Captives: How Stolen People Changed the World, University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Norman Cohn, Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith, Yale University Press, [1995] 2001.

Shannon E. French, The Code of the Warrior: Exploring Warrior Values Past and Present, Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

Bryan Hayden, The Power of Ritual in Prehistory: Secret Societies and the Origins of Social Complexity, Cambridge University Press, [2018] 2020.

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Robert L. Kelly, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum, Cambridge University Press, [1995] 2013.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377],1967.

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, [1990] 2011.

Steven Pfaff , Exit-Voice Dynamics and the Collapse of East Germany: The Crisis of Leninism and the Revolution of 1989, Duke University Press, 2006

Jared Rubin, Rulers, Religion & Riches: Why the West Got Rich and the Middle East Did Not, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Emmanuel Todd, The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems, (trans. David Garroch), Basil Blackwell, 1985.

Emmanuel Todd, The Lineages of Modernity: A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus, (trans. Andrew Brown), Polity Press, [2017] 2019.

Peter Turchin, War and Peace and War: The Life Cycles of Imperial Nations, Pi Press, 2006.

Yuhua Wang, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Articles, papers, book chapters

Eric Chaney, ‘Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present,’ Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2012, 363-414.

Eric Chaney, ‘Religion and Political Structure in Historical Perspective,’ Working Paper, October 2019.

Gregory Clark, ‘The interest rate in the very long run: institutions, preferences and modern growth,’ Working Paper, May 2005.

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77.

J. G. Hariri, ‘The Autocratic Legacy of Early Statehood.’ American Political Science Review, (2012), 106(3), 471-494.

Monika Karmin, et al., ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Resources, 2015 Apr., 25(4), 459-66.

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021).

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144.

David Schonholzer, Pieter Francois, ‘Environmental Circumscription and the Origins of the State,’ July 29, 2023.

Manvir Singh, Richard Wrangham & Luke Glowacki, ‘Self-Interest and the Design of Rules,’ Human Nature, August 2017.

Peter Turchin, ‘A theory for formation of large empires,’ Journal of Global History, (2009), 4(2), 191-217

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9, 2077.

Certain aspects of Homo sapien female sexuality make a certain grim sense in light of this history of those prepared to breed with their rapists, and the killers of their male kin, successfully having descendants.

This would select even more strongly for the team-building propensities of Homo sapien males.

Think of the Prussian, Polish, Hungarian and Russian aristocracies. Think of the worst true thing you could say of them. They were still better than the gauleiters and commissars that replaced them.

Post-Enlightenment Progressives (“the woke”) are social predators proclaiming themselves to be protectors. The welfare state colonises social pathologies.

A remarkable break-down, and build-up of what we have today in our complex systems of freedom and trade in the western tradition.

We, who reside between the edges of our homogeneous continents, indeed take for granted our natural shorelines as defensive walls. We forget our geographic luck to our peril.

Beautiful work, Lorenzo.

Great work here!