The expanding burden of the conveniently wrong

If there is no penalty for being wrong, people will be as wrong as it is convenient to be.

Look at anyone making consequential decisions. Ask the question: what penalty do they suffer if they are wrong? That is, what are the consequences for them if they adopt a belief that is not true; if they make a decision hostile to human flourishing; if they retard the operation of the organisation or society around them.

For a horrifying number of people in our modern, highly bureaucratised, highly regulated, highly taxed, highly subsidised societies, the answer is: nothing. Nothing happens to them if they are wrong.

Note, this is different from the question of: did you follow the correct process? It is relatively easy for failure to follow the correct processes to have consequences. The what-if-you-are-wrong question also applies to: what if you follow the correct process and are wrong?

The question of being wrong has lots of layers. Something can simply block good things from happening, but those good things’ lack of happening is typically invisible.

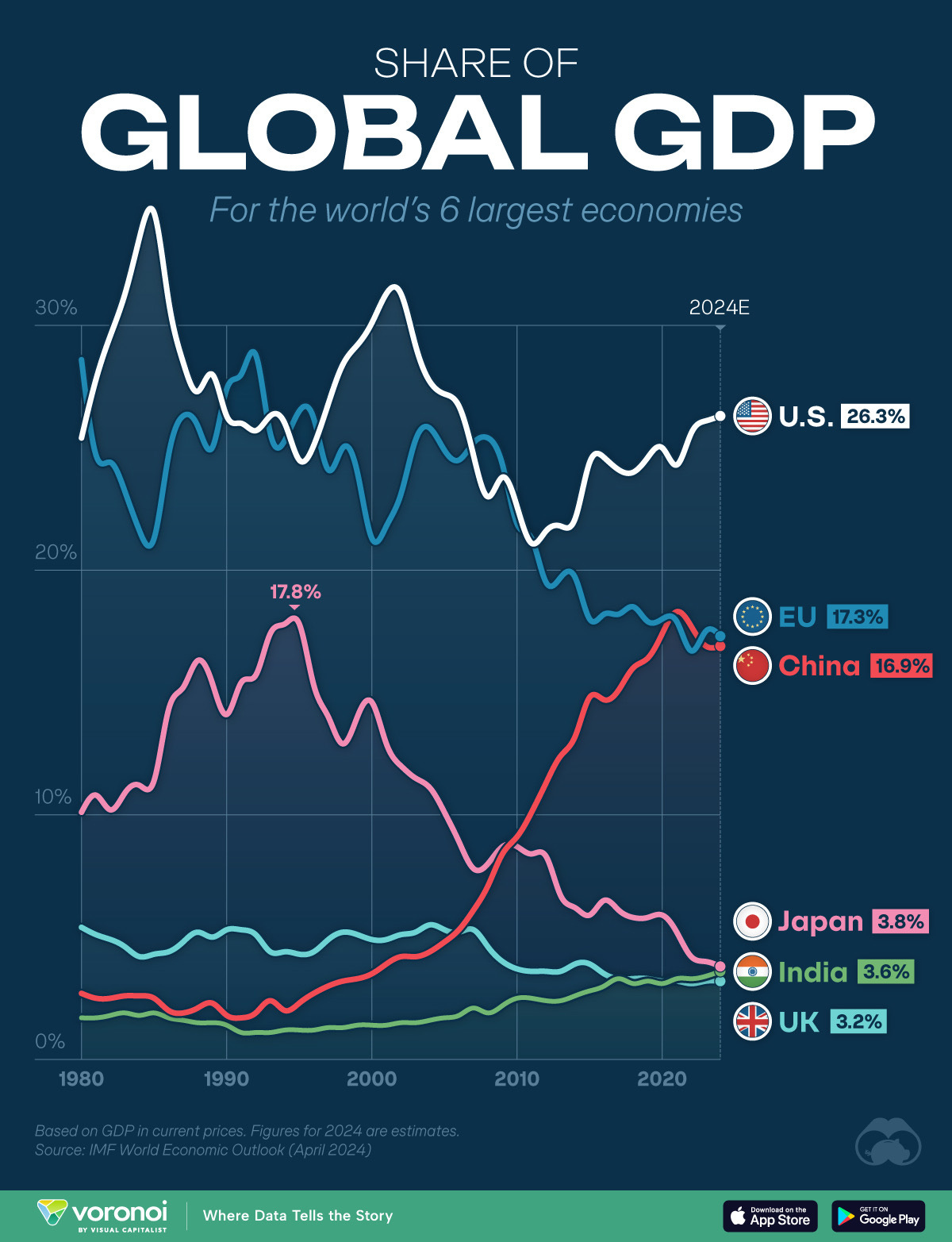

Economic stagnation is a normal condition of human societies, in large part because what is blocked from happening is invisible. Such has become more visible in the world since the 1820s, as mass prosperity has been demonstrated to be an achievable thing. Compare, for example, the post-2008 economic performance of the UK and much of the EU with, say, the US. But such is more visible only by comparison with other societies—we cannot directly observe good things that are blocked from happening.

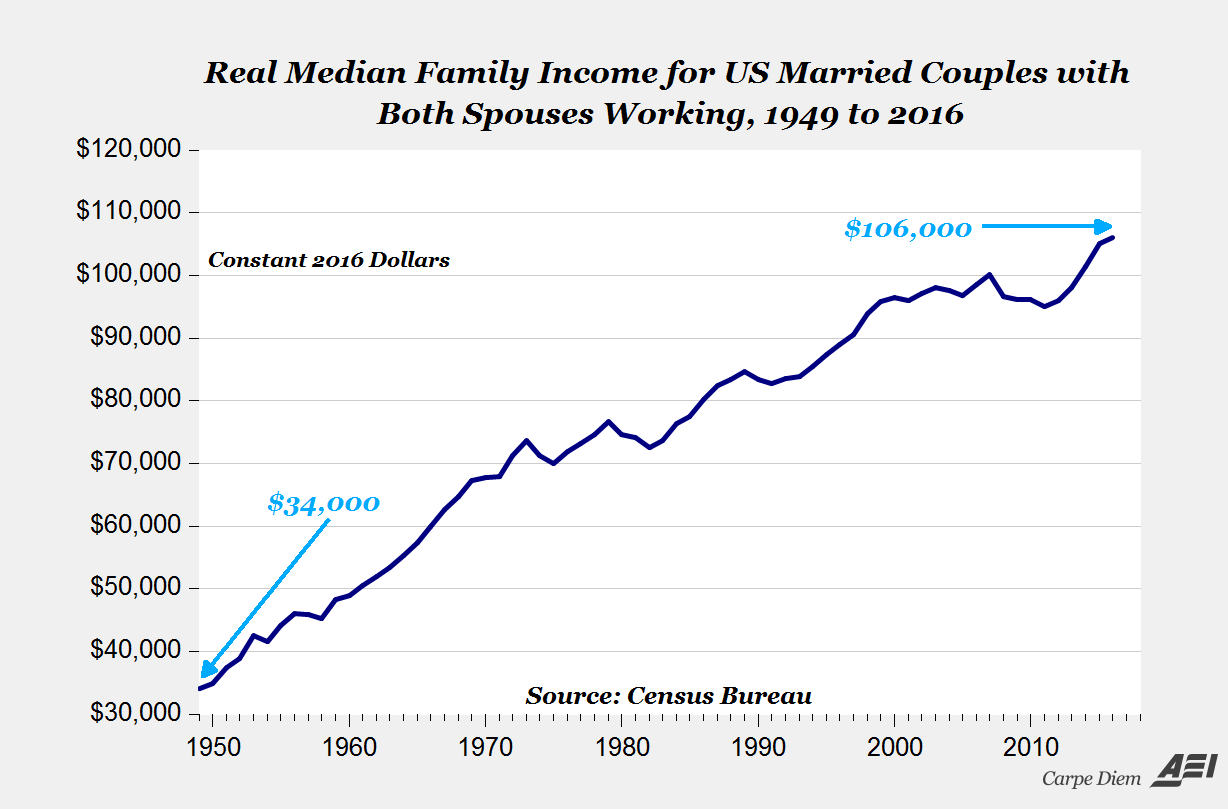

Even in the US, comparing the path of median incomes in different postwar periods shows that there has been a fair bit of blocking of good things from happening.

Moreover, comparison does not always resonate. People can not bother to compare or think that the comparisons do not apply. This time will be different has a great deal of wish-fulfilment appeal.

Across so much of modern societies, the what-are-the-consequences-of-being-wrong? question has the horrifying answer of no consequences to the person being wrong. (Real consequences, but very delayed, is not much better.)

I have already discussed this no consequences for being wrong with regard to the universities. But the same point applies across much of the non-profit world, the apparatus of the welfare state, etc. It applies intensely to UN bodies.

The end of the (anti-Soviet) Cold War in 1991 was a pivotal year in so many ways. Until then toxic ideas within Anglo-American academe—and Western academe generally—had inflicted their worst disasters on countries outside Anglo-America. After 1991, those toxic ideas increasingly infected Anglo-America itself. Yes, being packaged as elite status strategies was a key distribution vector, but it is also clear that the lack of an external existential threat, and the multiplication of people who suffered no consequences from being wrong, reached a certain critical mass, undermining the ability and willingness to fight off conveniently wrong toxic ideas.

The other aspect of the what consequences for being wrong? question is: what are the accountability mechanisms applying in practice? The answer is too often some version of: none, attenuated, weak or haphazard. Even if we ask what feedback mechanisms are operating?, it is often unclear that such feedback is grounded in consequences in a positive-for-human-flourishing way.

If you want a picture of bizarre, demented, feedback patterns hidden from any accountability, listen to Dominic Cummings explain how the Human Rights Act and government lawyers generate pervasive dysfunction within British government.

The delegated state

Let us consider what is known as the administrative state. That is, the issue of regulations by autonomous or semi-autonomous government agencies. It represents legislatures delegating legislative power to subordinate bodies.

Well, bodies that are formally subordinate. What accountability mechanisms do such bodies have? Typically, tenuous and somewhat intermittent ones. Some elected official or officials appoint the heads and boards of such agencies, who are presumed to control the organisation. If the agency’s performance attracts public attention—and if mainstream media does not subordinate its coverage to whatever accepting this makes you a good person narratives they are pushing—then there is some active accountability.

Generally, however, not attracting public attention is all you need to continue doing what you are doing. Which, of course, gives disproportionate leverage to those motivated and able to potentially kick up a fuss about what you are doing. Legislative oversight via Congressional hearings or Australian Senate Estimates committees or similar can provide some accountability, but much of that depends on the quality and motivation of the legislators (and their staff) and is intermittent rather than systematic (though the threat of it has some systematic effect).

Now, consider those regulators. How good is their knowledge base likely to be? No matter how conscientious they are, very limited is the answer. How well are they able to calculate the implications of the regulations they issue? Again, to a very limited degree. How quickly will the effects of those regulations show up? Often, very unclear. They can claim endless notional bad things stopped, but the good things stopped will remain invisible.

So, why does China dominate drone production? In part, because the US FCC banned drones operating beyond line of sight. China just builds drones.

Once you think through the knowledge problems of regulators, and add to that the public invisibility—so inadequate accountability—of a lot of such regulatory activity, the chances that the net effect of such regulation is socially positive is … low. After all, a lot of the reason for legislators to delegate regulating is precisely to make such regulation less visible and, as much as possible, not their problem. This overlaps with providing benefits to some constituency in a way that is insulated from the vagaries of future Legislative majorities: which is also insulation from the vagaries of future democratic feedback.

One should always be sceptical of shifting government activity from the more visible and accountable to the less visible and accountable. One should also be sceptical of shifting such decision-making from those who have to weigh up trade-offs across the society to those who have much more narrow considerations.

A case of this being done right is how Australian monetary policy operates via an agreement between the Treasurer (an elected official) and the Governor of the Reserve Bank. But central banks are unusually prominent agencies, inherently subject to a lot of public scrutiny.

Much of the problem with “technocracy” is that it presumes way more knowledge than is actually held by the technocrats; greatly narrows the consideration of trade-offs; and skirts (or worse) the accountability issues. So often, making things “less political” means either pretending one is not making such trade-offs; being very narrow in your consideration of trade-offs; or making trade-offs that do not bear much public scrutiny.

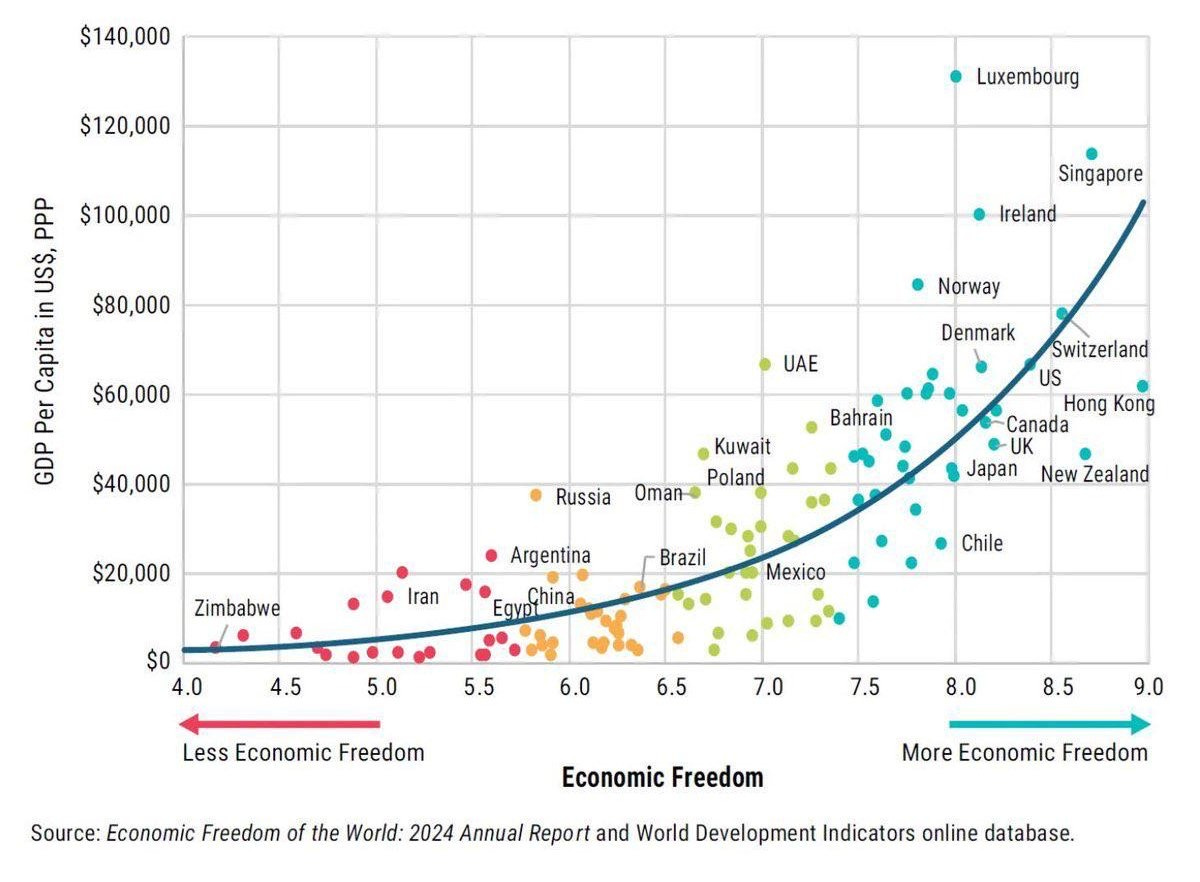

One of the strong patterns in the economic data is the positive connection between economic freedom and mass prosperity and economic growth. That is, the lower the transaction friction in a society—i.e. the easier it is for people to transact with each other—the more prosperous a society is. The lower the transaction friction, the less value-creating things are blocked from happening.

It is eminently possible to have laws that reduce transaction friction, that are transaction-friendly. Indeed, social pacification by the state is a huge boon to transacting. Nevertheless—particularly with detailed and specific regulation issued by subordinate agencies—regulation generally being net transaction-friendly is not the way to bet.

Ask yourself the question: what are the consequences to the regulators of being wrong? Ask the question: how much of the relevant knowledge do they actually have? Ask the question: how well can they calculate the full consequences of any regulation?

Ask yourself those questions, and you become way more sceptical of the regulatory efforts of the administrative state. Ask yourself those questions, and the strong association between economic freedom and economic growth and prosperity makes much more sense.

Being conveniently wrong

Now apply those questions more widely. Think about how many resources are consumed and diverted by people who suffer little or no consequences from being wrong. Think how, if they suffer little or no consequences from being wrong, they might then be conveniently (for them) wrong? Think how many resources can then be diverted to the service of those able to be conveniently wrong (e.g. the homeless-industrial complex).

Much of the malaise of modern societies makes a whole lot more sense if you ask (and answer) those questions. After all, if public health regulators are wrong about, for instance, nutrition guidelines, what are the consequences to the regulators, to the issuers of the guidelines of being wrong? (The US nutrition guidelines have been vastly improved, but the scale of the needed change is revealing in itself. We might also ask whether it is a good idea to have nutrition guidelines at all, given human variation.)1

If nutrition guidelines are wrong in ways that degrades the metabolic health of the population—so drives up public health budgets—how conveniently wrong are those nutrition guidelines likely to be? Especially as we Homo sapiens are very good at being self-deceptive in our own interests, in telling stories to ourselves about our noble motives. We are even better at it if we operate in networks with the same interests and perspectives. We are better still if there are social sanctions for dissenting, or raising awkward questions against, said convenient perspectives.

How many of the mis-steps over Covid were about what was conveniently wrong for the resources, reach, and authority of public health officials? The combined water, power, inflation crises in Iran provides an example of how appallingly dysfunctional a system built on being conveniently wrong can be.

A flourishing society is a balance between law and order; commerce and production; culture and connection. Systems positive for human flourishing systematically turn information into incentives, and incentives into information, in pro-social ways.

State apparats that are both overweening and dysfunctional—where both tendencies increase the other—have become interwoven with a careening techno-commerce without the shared sense of meaning or webs of connection to restrain either. Not least because the universities, publishing, the artistic and literary fields, and mainstream media have been actively sabotaging having such.

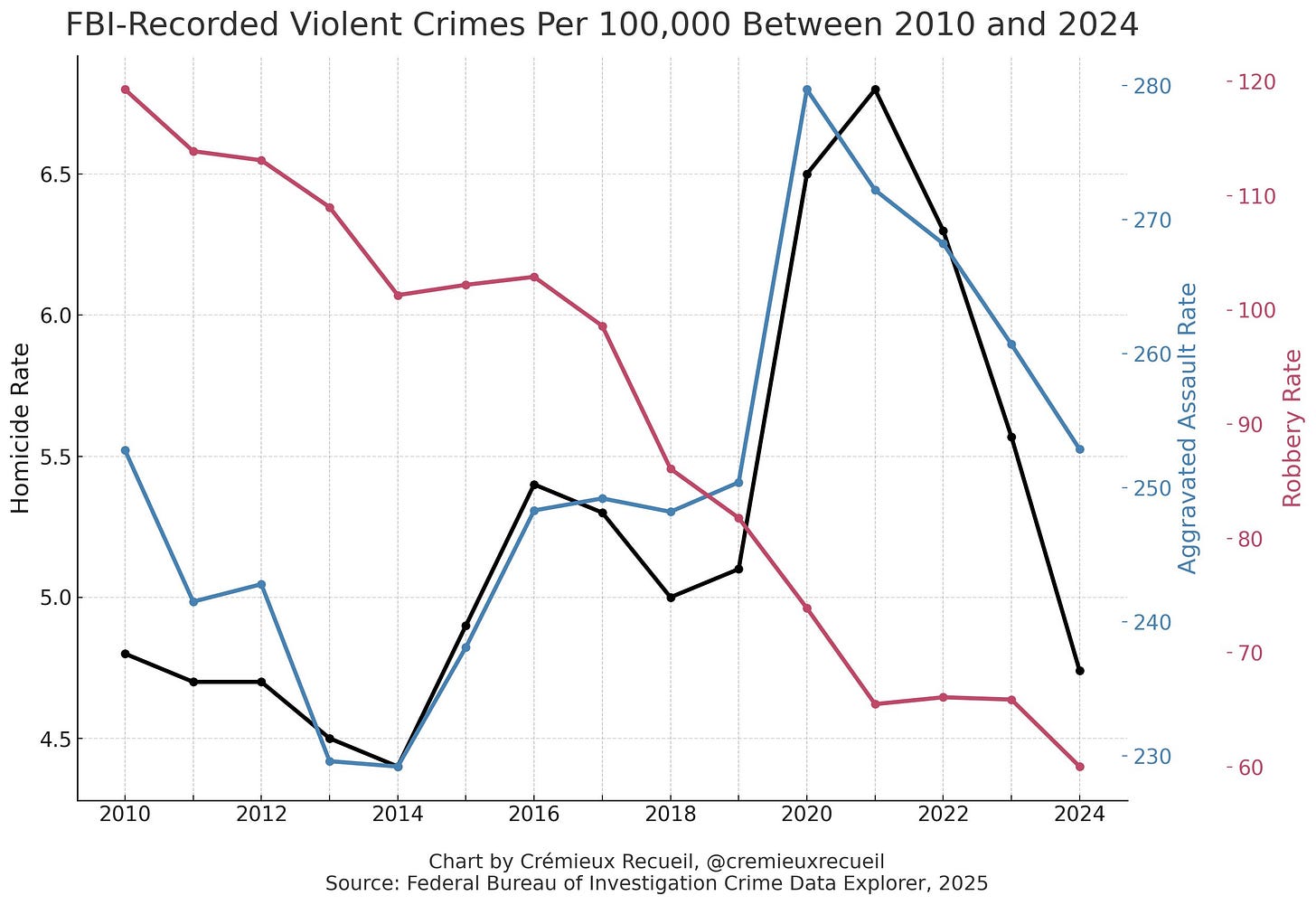

This creates societies both flooded with information and starved of it: full of media silos, information bubbles, and structural ignorances—see the above comments by Dominic Cummings. It creates anarcho-tyranny: states and local jurisdictions that are increasingly burdensome on the law-abiding but lax about crime and readily manipulated by organised minorities.

We live in societies that have been multiplying the range and ambit of people who benefit from being conveniently wrong because we increasingly live in societies of complex density with broken feedbacks that shield people from the consequences of being wrong. How many toxic ideas have come out of the academy—and then colonised government, non-profit and corporate bureaucracies—for precisely these reasons?

There are so many examples—all the Trans nonsense to start with, but also DEI and everything else derived from Critical Theory. The mountain of blank slate nonsense taught by the academy leaves people ill-equipped to apply evolutionary reasoning to, for example, imposing selection effects on a virus by targeting a particular protein or the likelihood of emergent phenomena in Artificial Intelligence.

This is not going to end well.

ADDENDUM: A post making similar points from a systems analysis perspective.

References

Sean P. Alvarez, Vincent Geloso, Macy Scheck, ‘Economic Freedom Matters A Lot More for Economic Development Than You Think!,’ George Mason University Department of Economics, Working Paper No. 23-14. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4368623

Joana Araujo, Jianwen Cai and June Stevens, ‘Prevalence of Optimal Metabolic Health in American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2016,’ Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, Volume 17, Number 1, 2019, 46–52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30484738/

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/137/1/1/6383014

Murray J. Horn, The Political Economy of Public Administration: Institutional Choice in the Public Sector, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

Thomas Sowell, Knowledge and Decisions, Basic Books, [1980] 1996.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011] 2013.

Given the complexities involved, it is hard to do nutrition science well. This makes it easy to do it badly, and even easier to do it to an agenda.

Very nice expansion on Sowell's dictum "It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.".

I am an old fart doing computer security work - which I have been doing for decades. We are all going to be wrong some of the time when we are making calls on incomplete information, but if we are wrong too much of the time we are out of work - deservably. It ends up being a surprisingly small community and your reputation is important - people you have worked with or for in the past remember you and your work. That reputation is important. I am well into my 70's and still going.

And sometimes you build your reputation by getting yourself fired. I once told a client about an issue that they clearly did not want to hear about - but it was in my opinion my responsibility to let them know that they had an issue that they needed to manage. My contract was cancelled the same day. My manager at my consulting company congratulated me - if the shit hit the fan, we could not be blamed for it - and assigned me to another project with a different client.

My youngest daughter is a civil engineer - and they work hard to not be wrong. They have legal liability as well as reputation to protect. Both are important.