Being a cultural species. Bravado in the absence of order (4)

Jens Ludwig’s ‘Unforgiving Places’ and what to do about them.

The previous three posts in this series—here, here and here—were a reworking of an essay published in Aero magazine in 2019. This reworking was prompted by listening to behavioural economist Jens Ludwig discussing his work with economist Glenn Loury and linguist John McWhorter followed by reading his deeply enlightening book. The reworking also incorporates reading and thinking I have done since.

The series concludes with this review of Unforgiving Places and a discussion of policy approaches that one might take in light of Jens Ludwig’s work.

Jens Ludwig’s book Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence is the distillation of decades of research on the patterns of homicide. This was actual on-the-ground research, not sitting in an office, building models from statistics. Jens Ludwig rode along with police; talked to—and listened to—people working in crime-ridden neighbourhoods; took notice of the observations of people who directly worked with the problem, what worked and what did not work; and tried to build explanations that reflected what people did, not what models said they would do.

The most obvious feature of homicide—and violence generally—is how much it is a matter of locality. Different localities in the same city can have hugely varying homicide rates. Simply comparing localities with very different homicide rates is informative. Unforgiving Places uses such comparisons to tease out what factors do, and do not, matter for homicide rates.

The book is very much an exercise in, and advertisement for, behavioural economics, which seeks to build models of human decision-making up from the patterns of human action. This is the opposite approach to that, for example, Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises takes in his magnum opus Human Action.

Behavioural economics has a spotty history. Nevertheless, respecting the constraint that everything social is emergent from the biological drives one to look at our evolved human cognition, and our biologically-given capacities and limitations, not assume disembodied rational calculators.

Jens Ludwig embraces the Thinking, Fast and Slow model from Nobel memorial Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s book of the same name. In the psychological literature, this is the System One and System Two approach. It is the broad approach that Ludwig uses, avoiding under-powered studies and replication issues: his work stands on its own merits.

Proactive and reactive aggression

While Jens Ludwig does not make this connection, this approach in looking at crime—and particularly homicide—works very well with primatologist Richard Wrangham’s analysis of proactive (intended) and reactive (in-the-moment) aggression, which use different brain circuits. Slow, System Two thinking generates pro-active aggression. Fast, System One thinking generates reactive aggression. This sort of consilience across disciplines encourages confidence in Ludwig’s approach.

Wrangham argues that, back in our evolutionary history, beta males got together and applied proactive aggression to systematically kill off the reactively-aggressive alpha males. In other words, our species systematically murdered its way to niceness.

We are the equal most proactively aggressive primate (along with Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes). We are the least reactively aggressive primate.

Less reactive aggression means higher levels of cooperation. Hence we are the most gracile—delicate featured—species in the genus Homo. We increasingly did not need facial protection against blows, but we did need to signal emotion, fostering cooperation.

We are also the only surviving species of genus Homo, because we evolved into the superior cooperators. This includes cooperation in proactive violence.

There is a lot of supporting evidence for Wrangham’s thesis, including male skulls with wounds in the back of their heads and anthropology showing that human foraging societies systematically and actively suppress dominance behaviour—including killing those who did not get the message.

Differing levels of reactive aggression

The other implication of having these two different types of aggression—supported by different brain circuits—is that different human populations, subject to varying selection pressures, will have different propensities to reactive aggression. Violence is very much a power-law phenomenon—it is dominated by a small tail of overwhelmingly males. So, having a larger “tail” of more reactively aggressive males in a set of lineages will generate higher rates of violence.

Women have more gracile faces than men as they are the physically weaker sex with (in evolutionary terms) bubs in tow. Childless women do not leave genetic legacies, at least not directly. What is selected for is successful child-rearing: hence bubs in tow.

Physical aggression against other adults—especially against males with, on average, almost twice their upper body strength—is a losing game for women. So, expressing emotion and signalling fertility is more important, hence the more gracile features of women compared to men and lower levels of physical aggression against adults.

Women do show the same level of physical aggression as men against children. Indeed, the more helpless the child, the more likely that the perpetrator of violence against them is female. Differences between male and female behaviour are a mixture of the innate and the strategic. Men and women are responding to different constraints, including being differently embodied agents.

As a general feature, the more important cooperation with other humans was for a set of lineages, the more reactive aggression would be selected against, so the more gracile faces can be expected to be in those lineages. The Arctic forager origins of East Asians, followed by densely populated irrigated farming and then a non-breeding underclass—due to a polygynous elite, one that came to be selected for by passing examinations—would have strongly selected for cooperation and against reactive violence. East Asians have highly gracile features, for both men and women.

The more important ecological pressures—independent of cooperation with other humans—the less reactive aggression would be selected against and the less gracile a population’s faces can be expected to be. Sub-Saharan Africa—being where Homo sapiens evolved—had lots of co-evolving pathogens, parasites, predators and mega-herbivores able to cope with humans. This kept human population density down and generated weaker selection against reactive aggression.

Lower population density made Africa the continent of slavery—grabbing an able-bodied human was more valuable than grabbing land. That Africa was the continent of slavery undermined trust, making cooperation more difficult. Africa was very much a continent of secret societies—these being mechanisms to solve cooperation problems.

Populations with Sub-Saharan African ancestry can thus be expected to have higher rates of reactive aggression. They also have notably less gracile faces. Similar points can be made about Australian Aborigines—lots of poisonous organisms, challenging foraging, low population density, notably less gracile faces. Both archaeology and observation suggests a high rate of violence among Australian Aborigines, indeed particularly against women.

How gracile female faces are in a set of lineages indicates how high the level of reactive aggression has been among the males in those lineages. The more facial robustness has been selected for in the female expression of genes—so the less gracile are female faces—the higher the level of reactive aggression among males in those lineages. The less facial robustness has been selected for in the female expression of genes in particular—so the more gracile the female faces—the lower the level of reactive aggression among males in those lineages.

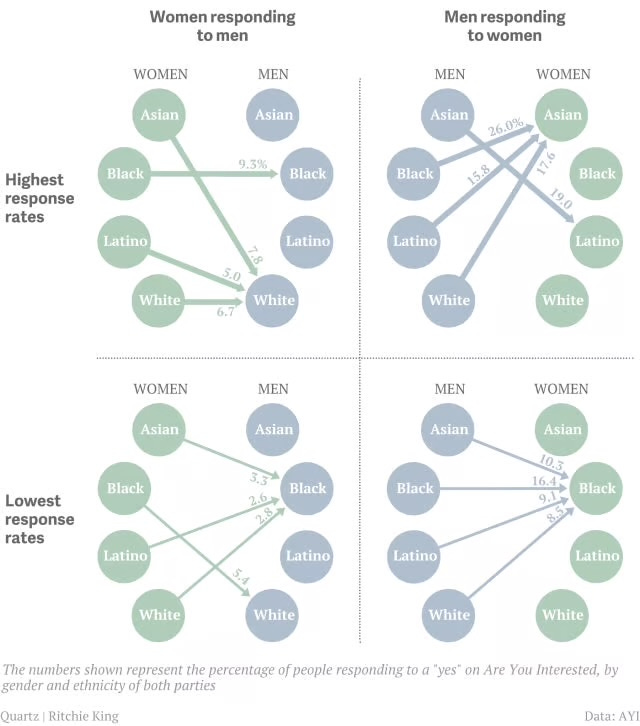

Differences in how gracile female faces are feeds into, for example, patterns discoverable from dating apps. Being “too” gracile is, however, generally not an advantage for males.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Sub-Saharan African diasporas persistently have higher rates of violent crime than do East Asian diasporas. This, however, does not get us very far, as rates of violence among Sub-Saharan African diasporas vary so much across time and place. It does mean that Sub-Saharan African diasporas will be more vulnerable to local failures of public order. There is, however, no reason to think that public policy is helpless in the face of higher rates of reactive aggression.

Note, this is differential selection for (or against) reactive aggression. No one who has studied East Asian history will claim it shows less proactive aggression; merely that East Asian populations are easier to pacify and show a higher propensity for successful cooperation.

The more general point is that instrumental—i.e. System Two/slow thinking/proactive aggression—homicides are greatly outnumbered by expressive—i.e. System One/fast thinking/reactive aggression—homicides. In the US, about 20-25 per cent of homicides are instrumental, the result of previously intended actions. Such violence comes from rationally calculated actions that mainstream economics takes as the staple of human action.

Conversely, in the US, about 75-80 per cent of homicides are expressive, the result of “in the moment” actions that mainstream economics provides very little leverage on but Jens Ludwig shows that well-applied behavioural economics can usefully analyse. Unforgiving Places is very much about taking the actual patterns of homicides and showing using the Slow/System Two and Fast/System one model of human decision-making provides a means to analyse and understand most homicides that mainstream economics—with its rational calculation paradigm—does not.

The structure of the book

Ludwig starts with a Preface that tells you a little of his experience in Chicago, both personal and scholarly, and notes the very different dynamics of particular areas of Chicago. This makes front and centre one of the key features of crime, especially homicide—that it varies so greatly by locality.

Chapter 1 (A New Idea) starts with an incident of fatal violence. Descriptions of such incidents pepper Unforgiving Places. Ludwig notes that the US has a much higher homicide rate than other developed countries—five times higher than the UK’s, for instance. He further notes the importance of shootings in that higher US rate and why mass shootings—even though they make the headlines—are not his focus.

Ludwig brings out that neither high rates of gun ownership (Canada, Switzerland) nor high rates of violence (the UK) generate high murder rates: it is the combination of the two that does (p.4). He then sets out the two conventional views about what drives homicide rates—root causes (poverty, inequality, deprivation, etc.) and violent predators: so bad people or bad circumstances. Following these approaches has had remarkably little success in reducing US homicide rates.

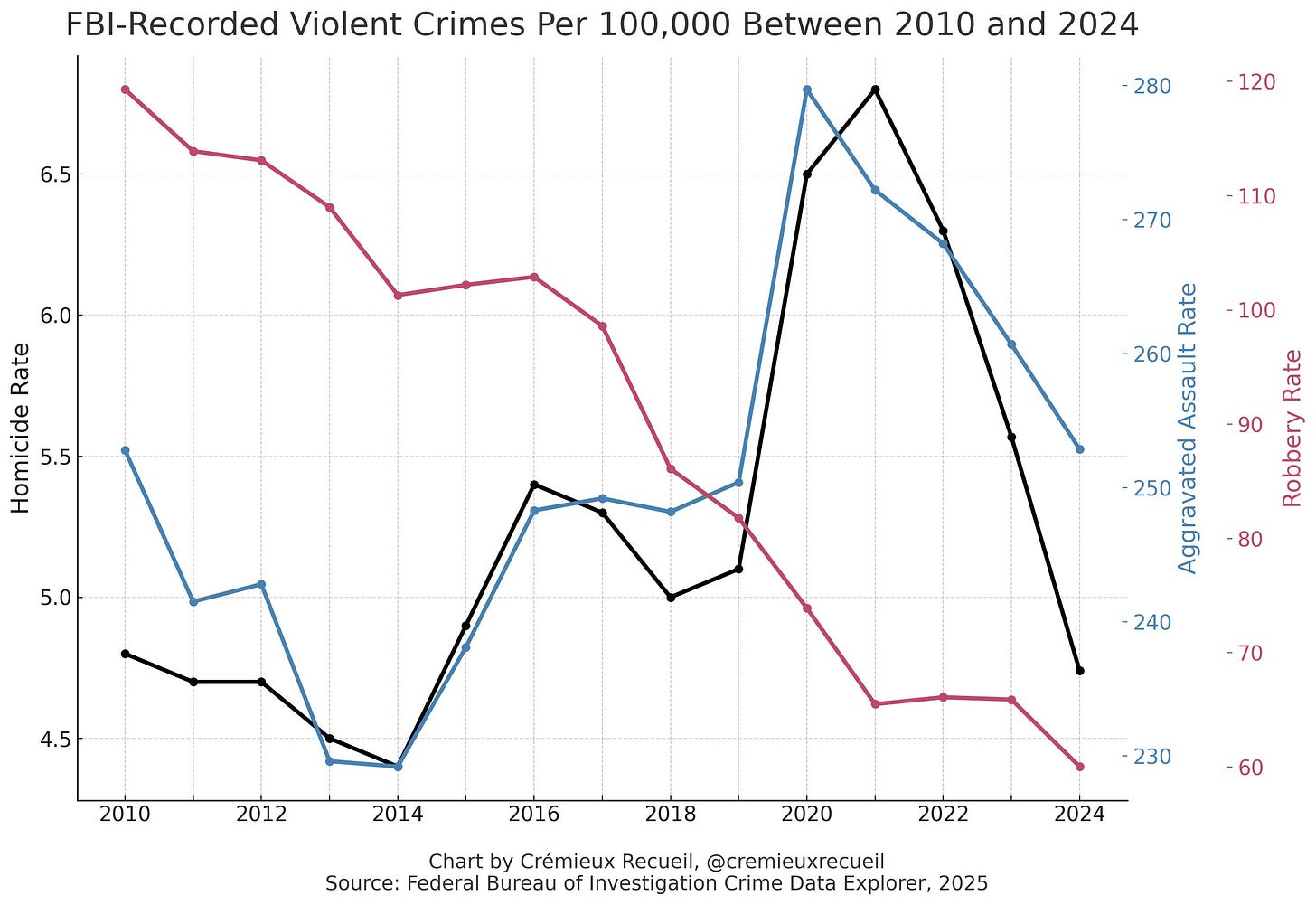

Ludwig compares two adjacent neighbourhoods in Chicago with majority African-American populations within the same police force and court jurisdiction—South Shore and Greater Grand Crossing. The latter has a much higher rate of shooting victims than the former, and persistently so. Indeed, looking at the graph comparing the two localities (p.10), the differences got worse during the post-Ferguson and post-George Floyd homicide surges.

Ludwig uses various deadly incidents described in the text to show that they do not make sense as an act of rational calculation. Nor, as he points out, does how much age is a predictor of homicide: the overwhelming majority of homicide victims, and even more of perpetrators, are young males.

Ludwig notes that both conventional views assume rational calculation, whether the emphasis the bad people explanation puts on deterrence or the bad circumstances explanation puts on incentives. He juxtaposes them with behavioural economics, which provides a handle on how situational so much human decision-making is. Ludwig cites both Nobel memorial Laureate Daniel Kahneman Thinking Fast and Slow/System One and System Two paradigm plus a 1970s “Bad Samaritans” social psychology study which found that the biggest predictor of whether people were helpful in a given situation was whether they were in a hurry or not.

Ludwig then tells a story of himself getting into a rage-filled confrontation and noting that part of why it de-escalated was a security guard intervened. The confrontation took place in a locality that had lots of what journalist and urban theorist Jane Jacobs referred to as “eyes on the street”: people known or expected to be present who could potentially intervene. I remember being in Padua, and a pharmacist came running out calling (I presume) “stop thief!” and every adult male in the area immediately converged on the suspect. Ludwig points out the dynamics of his confrontation does not make much sense in a rational calculator paradigm, but behavioural economics can explain it just fine.

Due to a very different built environment, less-homicides South Shore has a lot more “eyes on the street” than does more-homicides Greater Grand Crossing. Ludwig argues the more stressful and unpredictable a locality is, the more System One thinking is likely to be “overloaded”—and the more it is inclined to catastrophise—and so short-circuit more considered actions, leading to more violent, including fatal, confrontations. Similarly, the older we are, the more experience we have in dealing with situations.

In evolutionary terms, what is odd is not our fast “immediate reaction” thinking, but our slow, considered calculation thinking. Precisely because such “slow” considered thinking is a late developing system in evolutionary terms, we humans struggle with abstract thinking—consider all the junk social “science” and Theory our too-many-midwits universities produce.

As biological beings, our rationality has to be bounded: we are inherently cognitively and informationally limited, yet have to deal with changing circumstances. This means we have to deal with sudden shifts in salience, in what requires our attention.

We are conscious, so we can focus attention. We have a variety of perceptual systems, so we have more ways of assessing our environment, including being warned. We are self-conscious so we can communicate via language; so we can assess, assemble, transmit and receive, packages of information.

Ludwig explains that, while there are precursors in the scholarly literature, what he is seeking to do is to inject the behavioural economics perspective into public policy and public discourse on violence. In particular, he wants to stop public policy from making the situation worse, from creating too many “unforgiving places”. He concludes Chapter 1 by setting out the plan of the rest of the book (Pp27-30).

Chapter 2 (The Limits of Gun Control) critiques focusing on gun control; Chapter 3 (The Origins of Wicked People) critically examines the bad character approach; Chapter 4 (In Search of the Roots of Violence) critically examines the root causes approach; Chapter 5 (Vital Statistics) examines how most killings spring from arguments; Chapter 6 (Behavioral Economics and Gun Violence) looks at how most killings comes from visceral reactions to situations; Chapter 7 (Unforgiving Places) examines how and why localities vary so much; Chapter 8 (Weight of Evidence) presents evidence for the behavioural economics view; Chapter 9 (The Case for Hope) extends this analysis to suicide and police shootings and what all this suggests for public policy.

Perhaps the most striking idea—which Ludwig focuses on in Chapter 9—is that certain localities “overload” people’s cognitive capacities, making visceral reactions much more dominant. These are the unforgiving places of the title. This fits in with the way IQ is negatively correlated with violence: lower cognitive capacity means less ability to cope with unpredictable stress.

The unforgiving places have more confrontations where System One reactions dominate: in particular, more catastrophising System One reactions dominate (p.220). The more visceral reactions dominate, the more one’s propensity to reactive aggression is going to matter.

System One responses include intense feelings that can easily drive actions. This seems to be the dominant pattern in, for example, suicide and suicide attempts (Pp222-3). Suicidal emotional states can last one to three hours, but they typically pass.

So much of our cognition is not conscious, and that includes what drives and shapes our emotions. The more intense our emotions, the harder it is to shift to System Two thinking.

Police shootings also occur in moments of intense emotional arousal. Training police in recognising non-routine situations—and then in being less System One, more System Two in such situations—was found to substantially reduce police use of force, low-level arrests and racial disparities in arrests (Pp223-5).

Ludwig emphasises that the above are not psychological explanations. They are explanations relying on the dynamics of human decision-making (Pp225-7).

Ludwig argues that the behavioural economics focus on the dynamics of decision-making is consilient: that is, it enables the integration of range of explanations and information from a range of perspectives, including across disciplines. Note how easily I can bring primatologist Richard Wrangham’s analysis of reactive and proactive aggression into Ludwig’s analysis.

Part of what Ludwig is offering is an over-arching analytical narrative to hang a series of ideas together (Pp227-31). As he writes:

Environmental design. Violence interruption. Collective efficacy and informal social control. Neighbourhood effects and desegregation and residential mobility and community development. BAM [Becoming a Man], READI [Rapid Employment and Development Initiative], Choose 2 Change. Restorative justice. Gun control. We already have the start of some promising levers on hand. But without some underlying ideas about what drives gun violence, this set of policies can feel like a random grab-bag of things. (p.230, links added.)

Random grab-bags are not persuasive.

The long-term decline in homicide rates since the high medieval period came to an end around 1900 (p.230). Ludwig suggests that we have reach the limit of the general “civilising trend” that psychologist Steven Pinker points to in his writings, riffing off sociologist Norbert Elias’s “civilizing process”.

I would add that part of the problem is that process was significantly interrupted within various localities in the US (see the preceding posts)—and even more so in various localities in the Caribbean and Latin America. It also matters if one imports significant numbers of migrants from cultures who have not experienced the full process.

That we are such an imitative and status-conscious species is why it makes a difference whether immigrants are imported in small packets or large lumps. The former are much more likely to imitate the resident culture than the latter.

The greater the convergence in norms and expectations, the easier interactions become. Being a high-trust society has lots of advantages that poorly managed immigration can degrade. Changing the cultural patterns of a society can significantly increase transaction costs, so transaction friction in interactions.

System One, reactive aggression, confrontations are not very deterrable, precisely because of the intensity of emotions when folk are feeling threatened and tending to catastrophise. Ludwig notes that the US criminal justice system is often dysfunctional by simply being overloaded, so using behavioural economics to generate policies that prevent violence will make the system more functional (Pp231-3). He cites a study which found that simply having lots of police visibly present can increase crime prevention by up to 60 per cent (p.232) and that successful confrontations defusers often work best by appealing to self-interest rather than empathy (p.233).

The insights from Ludwig’s research and analysis suggests that teaching people better ways of thinking about their situations and actions can be effective (Pp 233-7). This can make both rehabilitation effects and schooling more effective. Part of what schooling does is teach better metacognition: thinking about thinking. Evidence suggests, for instance that a 10 per cent increase in school graduation rates can reduce murder rates by 20 per cent (p.236), though I wonder how much that simply comes from keeping excitable teenage males off the streets.

Ludwig argues that, rather than poverty causing violence, violence often causes poverty, using the examples of New York City (declining homicides, static population), Chicago (static homicides, falling population) and Detroit (rising homicides, sharply falling population) to make his point (Pp238-40).

Ludwig points out that many of the policies that have been adopted using bad circumstances or bad people conventional thinking have either failed or made things worse, while US cities are much more dangerous than comparable cities in other developed democracies. Meanwhile, pro-active policing policies in New York and Los Angeles had led to plummeting homicide rates (Pp241-4). There is no reason whatsoever to think public policy is “stuck” in high homicide equilibria.

Mechanisms

Jens Ludwig’s research and analysis fleshes out the mechanisms for the patterns discussed in the preceding posts in this series. When one looks at the level of homicides, gang violence is less important; premeditated violence is less important; so are mass shootings, however horrifying.

What dominates the homicide figures is bravado violence. Homicides that comes from an in-the-moment dispute that turns deadly because one or other of those in dispute has a knife or (especially) a gun, or easy access to either. Anything that interrupts such disputes—and their escalation—reduces homicide rates.

Given that, in the US, about 75-80 percent of homicides are “in the moment” killings, whatever:

makes personal confrontations more likely to happen

makes personal confrontations more likely to get physical;

such confrontations more likely to turn violent; and

such violence more likely to turn deadly,

will increase homicide rates. This is the spiral of violence. Anything that interrupts the spiral of violence reduces homicide rates. The ready access to guns makes the spiral of violence much more likely to be deadly.

Low homicide clearance rates means that more people are literally getting away with murder, which generates an increased incentive to defends one’s personal space, one’s “rep”.

This is why cops “on the beat”—and their relationship with the locals—matter. What cops do that matters most for homicide rates is interrupting the spiral of violence. When cops withdrew in the face of anti-police activism, that means they interrupt the spiral of violence much less, so homicides surge. Anti-police activism thereby kills, in a quite direct fashion.

Evolved decision-making

Where gathering information has a cost, attention is a scarce resource and cognitive capacity is limited, fast-and-frugal heuristics—ways of doing things: aka habits, routines, prejudices, customs, etc.,—are often going to be an advantage, and so be selected for. Indeed, culture can be understood as an evolved series of life-strategies sharing such heuristics. Life-strategies that evolve depending on what is reinforced within one’s social milieu.

Precisely because we have limited cognitive capacity, how we frame a situation is very powerful for how we react to it. This is why culture can matter so much to our behaviour, because our culture affects—often profoundly—how we frame situations. Our culture and experience embeds framings/patterns of belief (schemas) and patterns of action (scripts) into our brains.

We are a highly imitative and status-conscious species precisely because we are such a social species. Cultures that discourage confrontations, discourage confrontations becoming physical, discourage physical confrontations from becoming violent, discourage violent from becoming lethal, will generate very different rates of violent crime than cultures that do the reverse.

When we consider the spiral of violence, it becomes clear why, for example, crime rates vary so hugely between migrants from different cultures. To talk about “migrants and crime” in some general, interchangeable widgets, fashion is extraordinarily unintelligent and observationally wrong. We can see this in how Japanese migrants have a vanishingly low violent crime rate, Somali migrants a high one.

We use status as social currencies of cooperation and interaction. Prestige comes from displays of conspicuous competence, including—often especially—in risky situations. Prestige is a way of rewarding actions with positive benefits for others. Propriety comes from conforming to the accepted norms. Propriety—via stigma—is a way of punishing actions that cause negative consequences for others.

As social currencies of cooperation and interaction, prestige and propriety are mechanisms to get around free-riding problems in social interactions. They overlap—particularly propriety, that uses stigma as an enforcing mechanism—with norms. Norms generate robust expectations about behaviour that anchor social cooperation and interactions.

These are evolved mechanisms to foster cooperation, arising out of our highly cooperative subsistence and child-rearing strategies. The cooperation that makes our species such a spectacular example of the social conquest of the Earth. Different cultures harness these mechanisms in different ways.

Young males—who are the most likely victims of violence and even more so the likely perpetrators of violence—can feel the visceral urgency to defend their “rep”, to elevate their prestige, to stop being victimised, by defending their “social space”. In honour or bravado cultures, such prestige can be protective and a willingness to confront, even to escalate, elevates one’s prestige: feeling or seeking such prestige can, in itself, be emotionally rewarding.

Conversely, in a dignity culture, norms act to discourage confrontations happening in the first place while also providing more mechanisms to defuse them. This is particularly so if there are enough “eyes on the street” so that people, actively or passively, support the norms of non-confrontation and de-escalation.

Unless there is a clear understanding of the mechanisms of violence, policy language can dwindle into lazy sloganeering—e.g. “community policing”. Moreover, gang violence is generally not a large part of the violence problem in US cities. Even violence by gang members is often about personal interactions, though these can spill over into on-going feuds.

This makes the situation in US high-violence localities somewhat different from the situation in, for example, El Salvador, which was much more a matter of gang warfare and substitution of the authority of gangs for the authority of the state. Hence, massive incarceration of gang members has hugely reduced the homicide rate in El Salvador.

Beliefs as (disastrous) moral assets

What is absolutely useless—and worse than useless—is the left-progressive/“woke” approach of taking the “bad circumstances” analysis to the nth degree. Grading people by their “marginalisation”, and then treating them—i.e. excuse-making—accordingly does nothing to generate pro-social patterns of behaviour. Worse, it weakens the barriers against anti-social behaviour. Hence it leads to surges in crime. The most extreme example of this is BLM anti-police activism leading to police withdrawal and so generating surges in homicide in 2014 and 2020.

But “woke” Critical Constructivism “analysis” operates utterly differently from Jens Ludwig’s careful scholarship. It starts with Theory and then selects and grades evidence according to said Theory. Such Theory is selected on the basis of the imagined transformative future, setting up the splendour in their heads as the benchmark of judgement, thereby generating beliefs-as-(moral) assets.

Once the (moral) splendour-in-your-head becomes the basis of your moral judgement and identity, you and yours have a very strong incentive to police information to protect those moralised assets. What works is not the concern. What generates and protects the moralised assets in (left-progressive) heads becomes the concern. That is not going to lead to good policy: indeed, it demonstrably leads to the opposite. Alas, the sense of owning morality due to the moral splendour in your head is very good at motivating and coordinating people in networks primed to dominate organisations and institutions.

Policing

Meanwhile, back in on-the-ground reality: in high-violence localities, it is very important to have police “on the beat”. That means—as much as practicable—police walking or cycling around, rather than riding in cars as if an occupying force. It also means police trained in what works to defuse confrontations and to better manage the confrontations that do occur.

Clearly, there needs to be enough detectives and forensic services for the level of crime in a locality. The higher the homicide clearance rates, the less people get away with murder, the less the incentive there is to “self-help”. The key point to greatly improving homicide clearance rates is not to improve deterrence to commit crimes—though it will do that—but to massively reduce the sense of threat people (and especially young men) have to deal with in their localities.

Policing that interrupts the carrying of guns will encourage confrontations not to be lethal, both in the capacity to kill and in the sense of threat. If the carrying of guns is sufficiently interrupted, the self-protection incentive to carry them will be reduced. A positive downward spiral in over-ready access to guns can be set up. Legal guns are a bit of a lost cause in the US because of the Second Amendment, but illegal guns are not.

Police need to cultivate active connections with the local community to defuse confrontations and interrupt chains of confrontations. This includes identifying, and pro-actively dealing with, what is leading to such confrontations.

Streetscapes

Empty streetscapes are a bad idea. Lots of vacant lots and abandoned buildings are a bad idea.

Streetscapes need to encourage more “eyes on the street”. This means don’t zone so as to destroy diverse use of localities. Don’t create abandoned buildings by rent control. Turn vacant lots into parks and gardens. Don’t allow the streetscape to shout “abandonment”.

Encourage the development of locally-present people who can intervene and defuse confrontations. There is increasing amount of good evidence about what works, which can be spread by training and example.

Massive improvements are possible

Yes, different human populations have different rates of reactive aggression. But that is reactive aggression. The less there are situations that activate reactive aggression, the less violence there will be. Yes, the US in particular needs to actively work to have far fewer unforgiving places in its cities, but this is not remotely a hopeless task. Thanks to Jens Ludwig’s enlightening work, we have a much better roadmap about how to do that, and how to discover more ways of doing that.

ADDENDUM: It may be better to think of reactive and proactive aggression as different cognitive modules.

References

Robert P. Abelson, ‘Beliefs Are Like Possessions,’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 16, 3 October 1986, 223-250. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1986.tb00078.x

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Christopher Boehm, ‘Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy,’ Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No.3. (Jun., 1993), 227-254 (with Comments by Harold B. Barclay; Robert Knox Dentan; Marie-Claude Dupre; Jonathan D. Hill; Susan Kent; Bruce M. Knauft; Keith F. Otterbein; Steve Rayner and Reply by Christopher Boehm). https://lust-for-life.org/Lust-For-Life/_Textual/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp/ChristopherBoehm_EgalitarianBehaviorAndReverseDominanceHierarchy_1993_29pp.pdf

Bradley Campbell, Jason Manning, ‘Microaggression and Moral Cultures,’ Comparative Sociology, January 2014, 13(6):692-726. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272408166_Microaggression_and_Moral_Cultures

Christophe Darmangeat, ‘Vanished Wars of Australia: the Archeological Invisibility of Aboriginal Collective Conflicts,’ Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2019) 26:1556–1590. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10816-019-09418-w.pdf

Manuel Eisner, ‘Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime,’ Crime and Justice, 2003, 30:, 83-142. https://www.vrc.crim.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/manuel-eisner-historical-trends-in-violence.pdf

O¨rjan Falk, Ma¨rta Wallinius, Sebastian Lundstro¨m, Thomas Frisell, Henrik Anckarsa¨ter, No´ra Kerekes, ‘The 1% of the population accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions,’ Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2014, 49, 559–571. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3969807/

Raymond B. Fosdick, Crime in America and the Police, Century, 1920. https://archive.org/details/crimeinamericapo00fosd

Chris D. Frith, ‘The role of metacognition in human social interactions,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2012, 367, 2213–2223. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3385688/

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

Pauline Grosjean, ‘A history of violence: The culture of honor and homicide in the U.S. South,’ Journal of European Economic Association, 2014, 12 (5), 1285–1316. https://www.uts.edu.au/globalassets/sites/default/files/121017.pdf

David D. Haddock and Daniel D. Poisby, ‘Understanding Riots,’ Cato Journal, Vol.14, No.1 (Spring/Summer) 1994, 47-157. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/1994/5/cj14n1-13.pdf

Bryan Hayden, The Power of Ritual in Prehistory: Secret Societies and the Origins of Social Complexity, Cambridge University Press, [2018] 2020.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Books, [1961] 1992.

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Kawalerowicz, Michael Biggs, ‘Anarchy in the UK: Economic Deprivation, Social Disorganization, and Political Grievances in the London Riot of 2011,’ Social Forces, Volume 94, Issue 2, December 2015, 673–698. https://www.academia.edu/7634221/Anarchy_in_the_UK_Economic_Deprivation_Social_Disorganization_and_Political_Grievances_in_the_London_Riot_of_2011

David S. Kirk and Andrew V. Papachristos, ‘Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neighborhood Violence,’ American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 116, No. 4 (January 2011), 1190-1233. http://users.soc.umn.edu/~uggen/Kirk_AJS_11.pdf

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Glenn Loury and Rajiv Sethi, ‘Crime and Punishment in a Divided Society,’ no date. https://www.qmul.ac.uk/sef/media/econ/events/Crime-and-Punishment.pdf

Jens Ludwig, Unforgiving Places: The Unexpected Origins of American Gun Violence, University of Chicago Press, 2025.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Nathan Nunn and Diego Puga, ‘Ruggedness: The Blessing of Bad Geography in Africa,’ The Review of Economics and Statistics, February 2012, 94(1): 20–36. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/nunn/files/ruggedness.pdf

Nathan Nunn and Leonard Wantchekon, ‘The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa,’ American Economic Review, December 2011, 101 (7): 3221–3252. https://dash.harvard.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/7312037d-191b-6bd4-e053-0100007fdf3b/content

Brendan O’Flaherty, Rajiv Sethi, ‘Homicide in black and white,’ Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 68, Issue 3, 2010, 215-230. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094119010000343

Colin Pardoe, ‘Violence and warfare in Aboriginal Australia,’ in Geoffrey Clark, Mirani Litster (eds), Archaeological Perspectives on Conflict and Warfare in Australia and the Pacific Book, ANU Press, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Colin-Pardoe-2/publication/359093125_Violence_and_warfare_in_Aboriginal_Australia/links/6316dca6acd814437f0909aa/Violence-and-warfare-in-Aboriginal-Australia.pdf

Christian Rudder, Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking), Fourth Estate, 2014.

Jonathan St. B.T. Evans, ‘In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning,’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.7 No.10 October 2003, 454-459. https://faculty.weber.edu/eamsel/Classes/Methods (3610)/Old Sections/Fall 2010/Fall 2010 Project/Evans (2003).pdf

Rajiv Sethi, Brendan O’Flaherty, ‘Homicide in black and white,’ Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 68, Issue 3, 2010, 215-230. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094119010000343

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

David Sun, ‘Arctic instincts? The Late Pleistocene Arctic origins of East Asian psychology,’ Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, Online First Publication, March 3, 2025. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2025-88410-001.html

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Richard W. Wrangham, ‘Two types of aggression in human evolution,’ PNAS, January 9, 2018, Vol.115, No.2, 245–253. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1713611115

Nice — going to have to save for later and read the whole thing. Looking forward to binge reading this

This has been an excellent series. As usual, chock-full of insights.