The Newtonian delusion: there is nothing so dated as a vision of the future

Social mechanics or social dynamics?

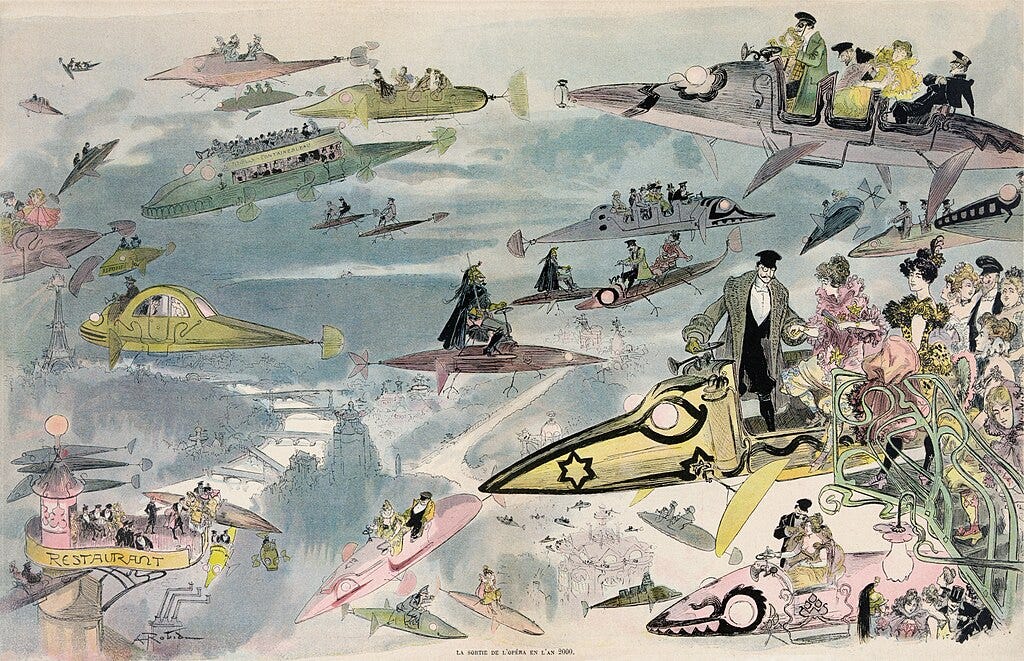

I have been a Sci-Fi guy since I started to read. Fortunately, I read Jules Verne early on, so I grasped as a young lad a fundamental principle of futurism—there is nothing so dated as a vision of the future.

Jules Verne wrote memorable stories, but his future tech (and society) was an extension of the C19th he was living in. It had to be for the reason philosopher Sir Karl Popper gave in his critique of Historicism—we cannot predict the future of knowledge, so of technology, so the social consequences thereof. This is a point that economists have since extended to—you cannot predict what new information there will be.

Jules Verne extrapolated from what was around him. He was a fine yarn-spinner, but his vision of the future is very dated: inevitably so.

Visions of the future are not only Sci-Fi. They can also be social or political visions of the future.

In his enlightening study of the idea of Revolution, The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin, historian Dan Edelstein contrasts the pre-Enlightenment notion of Revolution—a disastrous collapse in political order, so the point was to create a political order that avoided revolution—with the Enlightenment notion of Revolution as a means of creating a political (and social) order that transcends, indeed wipes away, the failures of the past.

The description by the historian Thucydides of the horrors of the Corcyraean disorders (c.436-433BC) cast a very long shadow over Western political thought. Not long enough, it turned out, as various modern revolutions have massively eclipsed their C5thBC precursor in tyranny and mass murder.

Not that the Classicals used the term revolution exactly. When the historian Polybius wrote of the movement—often violent—between forms of government, he used the term anakuklosis (anacyclosis), meaning a repeating cycle.

Classical Greek authors such as Plato and Aristotle saw violent social disorder (stasis) as the thing to most avoid. It was not the same as regime change (metabole). You could have either without the other. These terms were later rendered in Latin as seditio (sedition) and mutatio or transmutatio (mutation) respectively. The term revolution was very much a post-medieval development.

The shadow of Newton

All C18th Enlightenment thinking arose in the shadow of Newtonian physics, a very mechanical view of the Universe. It is known as Newtonian Mechanics for a reason. Precisely described objects responded in predictable way to identifiable forces. Mechanics either denies agency, or uses postulated uniformity to render it predictable.

In Maps of Meaning, psychologist Jordan Peterson nicely defines myth as a forum for action. Alexander Pope’s famous epitath expresses the Myth of Newton:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid by night.

God said, ‘Let Newton be!’ and all was light.

People became entranced by the Myth of Newton as the model for apparent all-encompassing understanding, rather than retaining a sober humility regarding what science was about.

The obvious success of Newton in expanding human understanding of the physical universe generated the notion that other areas of reality—particularly social reality—could be successfully analysed and described in terms of a single Theory. That social mechanics could also be accurately described and analysed in the same way as Newton had with his physical mechanics.

This also implied that social mechanics could be accurately controlled and predicted. Humans simply had to find the truth of these things, put them together in the way Newton had [with physical mechanics], and a future of sublime human felicity could be created.

This not only had scientific urgency, it had moral urgency. For what could be more important than creating that sublime human future? Diderot, editor of The Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts and Crafts), told the world:

Whoever fails to seek truth ceases to be human, and should be treated by fellow humans like a savage beast; and once truth has been discovered, whoever refuses to follow it is insane or morally evil.

How did we know that truth had been discovered? This was the Enlightenment version of error has no rights. This sentiment presages the Reign of Virtue in Revolutionary France enforced by the guillotine.

Newton’s mechanics turned out to be an excellent description of physical reality—except for very large scale and very small scale things. So, it was accurate across a wide range of phenomena, but not all. It is not false, exactly, but it is limited in its range of accuracy. Which made Newtonian mechanics not nearly the all-conquering example it had appeared to be.

Nevertheless, C18th social thought and C19th social science very much grew up in the shadow of the triumph of Newton and Newtonian mechanics. Marx’s pretensions to have unlocked the science of history, and its social mechanics, very much falls within this pattern. He was, of course, wildly wrong, but the ambition is clear; as is why the claims of Marxism had such allegedly scientific resonance. The entire notion of scientific socialism builds on the example, and [misleading] Myth, of Newtonian mechanics.

This sense of unlocking social reality on the Newtonian model also included the emerging discipline of Economics—especially Marshallian Economics, with its equations and graphs. This continued all the way to the Samuelsonian view of Economics as a Social Physics, with humans acting as predictable social particles. This ambition was apparently vindicated by mainstream Economics identifying quite a wide range of robust predictions of general tendency. Concepts such as gains from trade, opportunity cost, and comparative advantage are genuinely enlightening.

Mainstream Economics has, however, a similar problem as Newtonian mechanics, only worse: it does not work for nearly as wide a range of phenomena as it aspires to.

Economic exchange—particularly commerce—has powerful tendencies to common patterns across human societies: far more so than most human endeavours. People are dealing with the same basic factors of production (land, labour, capital); with problems of coordination thereof; problems of information and risk; with the strong feedback pattern of do you end up with more or less valued resources?

You even get similar antagonisms to market-dominant minorities across societies—a mixture of envy; the gains from commerce being sufficiently mysterious to outsiders that they can seem like some sort of fraud, con or parasitism;1 and reaction against the strong interior trust and reputation networks clannishness that make for successful market-dominant minorities in the first place.

The further human endeavours move away from the common patterns of economic exchange, the weaker mainstream Economics operates as an analytical tool. This has become very clear—even catastrophically so—with mass migration.

Treating countries as primarily places where economic transactions happen has proved to be a profoundly inadequate framework for analysing mass migration. In particular, the problems of the social commons—the combination of the institutional commons and social infrastructure—have been almost entirely ignored in conventional Economic analysis of migration, as therefore have most of the actual and potential costs and dangers of mass migration.

An institution is any complex social form that reproduces itself, such as legal systems. They are sets of rules, expectations and supporting norms used by a population to organise repeated activities.

It has become very clear that formally similar institutions can operate very differently in different societies because expectations, supporting norms—and the schemas (cognitive framings) and scripts (patterns of action) that underpin them—can vary dramatically between cultures.

An institutional commons is the interacting institutions within a territory that cover conflicts between institutions, or other individuals or groups, by having default arbitrators (such as rulers, councils and courts) and rules with remedies (law).2 This requires effective social infrastructure: patterns of norms, expectations and social connections that sustain cooperative behaviour, including pro-social institutions.

These can be degraded by mass migration. This is not a mere theoretical possibility. In his study Without Consent or Contract, economic historian Robert Fogel showed how mass migration broke the American Republic along its fault-line of slavery. More recently, Palestinian migration broke Lebanon along its ethno-religious fracture lines.

Especially given the The Loury principle of relations (connections) before transactions—people spend around 20 years or more embedded in connections before they start engaging significantly in economic exchange—culture very much matters. Not least because people can frame the same circumstances very differently. As humans, we cognitively model significance, not facts, and significance can not only vary between individuals, it can and does systematically vary by culture.

This means that people are not economic particles behaving in singular ways. Which means we are not dealing with Newtonian-style social mechanics. What we have instead is social dynamics, full of agents with varying framings, patterns of action and social strategies acting in varying ways even in the same circumstances. Hence formally similar institutions behaving in different ways in different cultures and behaving in different ways if the norms and expectations of the population changes—for example, due to importing sufficient numbers of people with different norms, expectations, framings, patterns of action, life strategies: i.e. cultures.

The technocratic ambition of manipulating social mechanics to a unitary social outcome is a fool’s errand. This even without all the Seeing Like A State problems or the (related) Hayekian problem of coercion suppressing knowledge while choice far more effectively generates, reveals, and uses, knowledge.

This cognitive over-reaching is not some minor failing of the technocratic delusion. It is a recipe for various levels of social catastrophe.

Resilience versus efficiency

Mainstream Economics also suffers the deep flaw—which is particularly salient in its failures to analyse migration correctly—in that it considers social mechanics as being primarily a problem of efficiency, of getting the most from available resources.

The technocratic ambition—of which Marxism is the most grandiose example—moralises a singular future to be achieved by the “right sort” of focused efficiency. Hence Marx’s patron and collaborator Engels extolling the “administration of things”.

Something that mainstream Economics and Marxism have in common—Marxism being the application of Hegelian dialectics to English political economy—is systematically under-rating problems of resilience. This goes back to the way Enlightenment thought was so dominated by the model of Newtonian mechanics, including the notion that social conflict could be resolved with appropriate understanding of social mechanics. As Dan Edelstein puts it:

Where classical philosophers derived constitutional principles from the irreducible divergence of social views, their modern, Enlightenment counterparts would base their theories on the future convergence of public opinion. This projected resolution of differences was a property of the modern view of history in terms of gradual, rational progress. Because the ancients did not think consensus was possible, they aimed to prevent revolution; for the moderns, revolution would bring consensus in its wake. (Pp39-40)

The Classical notion of political order was that social conflicts and tensions were inevitable. The trick was to create a “mixed” political economy that could best navigate the shocks of an unfolding future. This idea was expressed by various Classical authors, such as Thucydides and Aristotle, but most thoroughly by Polybius.

The US Constitution was quite explicitly constructed as such a Polybian mixed political economy, with a “monarchical” President, an “aristocratic” Electoral College, Senate and Judiciary and a democratic House (and juries). This is not a structure for efficiency, but for resilience. It is also not a mechanical model, but a dynamic one—the various forms of distributed power would actively balance off against each other; actively keep each other in check.

Risk management in commerce is also more about resilience—the ability to navigate shocks, changes in circumstances—than efficiency. Resilience and efficiency are often in tension with each other, not least because resilience regularly requires redundancy or some other flattening of variability, purchased at some cost in efficiency.

Just-in-time supply chains can be very efficient. They are not—as was demonstrated during the recent pandemic and its responses—nearly as resilient.

Often, risk management is about reducing the danger of breaching some threshold. Thus, peasants working in societies where it is risky to rely on stores—and even more on loans—to transfer resources and liabilities across time will often have dispersed small fields rather than a large consolidated one.

This is less efficient—their average level of production will be lower, as they are sacrificing economies of scale. But it is more resilient, because a failure in one field is much less likely to occur across all their fields. The risk of falling below the threshold of starvation is reduced by sacrificing efficiency to achieve greater resilience.

Across history, policy makers regularly balanced efficiency against resilience. The obsession that mainstream Economics has with efficiency—and its consequent downgrading of resilience—has done considerable damage to Western societies.

Ignoring Darwin

The power of the example of Newtonian mechanics was invidious in a further way. It meant that the social sciences—by looking to create some sort of Social Physics—almost entirely ignored the Darwinian revolution in Biology.

Biology is not a science of mechanics. It is a science of dynamics based on agents that make varying choices, where efficiency serves resilience.

Biological systems select for good-enough efficiency as they have to deal with constantly shifting circumstances and to avoid fatal thresholds. What is salient to an organism or biological system keeps changing. This is why organisms have a range of perceptual systems and why being conscious—the capacity to pay (and shift) attention—evolved.

A biological system has to be efficient enough to deal with what is currently salient from its available resources but also be able to shift attention and resources to the next salient thing while being robust to various shocks. Achieving such robust responsiveness is not the same as ringing the last bit of efficiency out of a specific biological system.

Good-enough is what is selected for. Hence, biological systems satisfice rather than maximise.3

For instance, organisms vary in how much they invest in different perceptual systems, depending on what works for their particular ecological niche. Hence, human eyes generate much more information, and more precise information, than does our sense of smell.

That much of social science was—implicitly or explicitly—based on blank slate notions of human nature that evolutionary biology demonstrates are false also creates a large barrier to incorporating evolutionary biology, and evolutionary anthropology, into the social sciences. But much of the appeal of such blank slate notions was precisely the support given to notions of a singular, morally transcendent, future achieved by “correct” understanding and manipulation of social mechanics.

The more malleable human nature is, the more that could be achieved by manipulating social mechanics. Media Effects Theory, for example, presumes a hugely overblown level of human malleability.

The more Homo sapiens have inherent cognitive structures and patterns, the less plausible any notion of creating a singular transcendent future becomes, and the better the past is as a guide to the future. The more also social science disciplines would have to defer to evolutionary biology and evolutionary anthropology. This is a fatal blow to the enticing vision from the Myth of Newton—from the example of Newtonian mechanics—of being masters of Theory, and so of social action and social outcomes.

Rather than the grand transcendent future, a far better guide is the Polybian notion of using past experience to construct resilient political (and social) orders. For the basic Polybian claim—that human nature does not change much and the past is the best guide to the future—is vindicated. Those would-be Masters of Theory would not only have to defer to the findings of evolutionary Biology, they would become just part of the parade of history rather than its Masters.

That was the grandest ambition from the example of Newtonian mechanics: to thereby become the Masters of social mechanics—so of the transcendent human future—not “mere” custodians of an evolving but continuing heritage transmitted across generations. Much of the dysfunction of contemporary Western academe comes from the arrogant moral grandiosity of being Masters of History rather than the humility of being custodians serving and transmitting a continuing heritage.

Emergence

Biology is very much about emergent phenomena, another tension with Newtonian mechanics as a model. Everything social is emergent from the biological. The Myth of Newton fed into the top-down visions of social action that extend back to Plato.

Platonism probably is a good way to think about mathematics, as the science of structure that deals with pure archetypal ideas. Platonism is a dreadful way to think about the biological or social worlds. As historian of ideas Etienne Gilson puts it:

Pure ideas … are born within the mind and from the mind, not as an expression of what is, but as models, or patterns, of what ought to be; hence they are born revolutionists. And this is the reason why Aristotle and Aristotelians write books on politics, whereas Plato and Platonists always write Utopias (Pp54-5).

Racism is very Platonic—every individual member is an avatar of some common archetype. The “woke” (Critical Constructivist) notion that teenage males with low melanin content are somehow morally stained by what particular European males did decades, or even centuries, before those teenagers were born is also very Platonic.

Noting that biological complexity has increased over time can easily generate a teleological notion of how biological reality operates that then feeds into notions of History having a Direction to be discovered. In reality, it takes time for the mechanisms to support biological complexity to evolve.

Consider sexual reproduction. It is a complex way to reproduce. That very complexity is an advantage, because each required stage in the process acts as a filter. What makes it through those filters is more likely to be worth the biological investment. Sexual reproduction also means constantly “throwing” the genetic die, enabling species to more explore more widely the strategy space of successful propagation, expanding the “pay off” from biological complexity.

Hence, the evolution of sexual reproduction has meant a dramatic increase in the number and variety of complex organisms. Above a certain level of complexity, species are all sexually reproduced, because complexity is both filtered for and strategy-space-exploration pay-off from complexity increased. But the way lineages go through many different species creates both difficulties in defining species and shows how wrong-headed notions of individual members being instances of some archetype of their species are.

So yes, there is a strong tendency within the biosphere to increasing biological complexity over time. But this is an emergent phenomenon, it is not a result of some inbuilt teleology. While concepts of spontaneous order can be over-done, such order is a feature of both biology and the social emergent from it, however inconvenient that is to the pretensions of the Myth-of-Newton Masters of Theory, of the Proper Direction of History, Platonists.

A mind, not a computer

The Myth and example of Newtonian mechanics has also had a distorting effect on thinking about human cognition. The notion that the human mind is a biological computer that models facts is very much one of cognitive mechanics.

But humans do not model facts, we model significance. We use information to serve our directedness. Indeed, as self-conscious beings, we humans use and package information to serve our intentions. Intentionality is not a matter of mere computation, it is not a mechanical operation.

Physicist Sir Roger Penrose argues that Godel’s Incompleteness Theorems demonstrated that human minds are not just computers. That we can recognise something is true whose truth cannot be demonstrated by computation. Whether or not he is correct, neither intuition nor emotion nor creativity are computational activities.

Conclusion

Newton’s mechanics was one of the great intellectual achievements of human history. But the obvious greatness of the achievement led folk to be over-impressed by it as a model for understanding reality: especially social reality.

As a model for dealing with biology, and everything that emerges therefrom—which includes all social phenomena—Newtonian mechanics has proved to be hugely misleading. Biological beings are not machines; they have dynamics rather than mechanics; human cognition is not merely computational; social dynamics are not social mechanics; humans are not social particles whose behaviour can be predicted by some Social Physics but agents with varying framings, strategies and reactions to circumstances; social resilience matters at least as much as efficiency.

Moreover, Polybius had a point. The trick really is to create resilient political and social orders that can work with human nature, that can deal with inevitable social conflicts, and that can respond resiliently to unfolding events.

Masters of Theory, Masters of social mechanics, technocrats are very much not what you want. Historically-informed folk who can use expertise, while being embedded in effective feedback structures that select for both capacity and character: that is the ticket. Examples of such leaders include Lee Kuan Yew, Sir Seretse Khama and Jose Figueres Ferrer.

This is not, however, what we have in Western societies. Instead, increasingly, we have toxically self-serving bureaucracies that notionally select for capacity and not at all for character—or even have adverse selection for same—plus an academe deformed by far too many self-satisfied Masters of overblown Theory, who are far too grandiosely arrogant to engage in the humility of custodianship, or the transmission of the hard-won wisdom of the past, but instead denigrate and undermine both.

This will not end well.

ADDENDA: Just to be clear, nothing in this post is intended to be a critique of Newton or his Mechanics, which was a profound achievement. One whose positive implications extended beyond Science. A thought-provoking paper argues that the acceptance and spread of Newtonian Mechanics had much to do with why the Industrial Revolution started in Britain.

References

P. W. Anderson, ‘More is Different,’ Science, New Series, Vol. 177, No. 4047. (Aug. 4, 1972), 393-396. https://cse-robotics.engr.tamu.edu/dshell/cs689/papers/anderson72more_is_different.pdf

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Dan Edelstein, The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin, Princeton University Press, 2025.

J. Doyne Farmer, Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World, Allen Lane, 2024.

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989] 1994.

James Franklin, What Science Knows: And How It Knows It, Encounter Books, 2009.

Chris D. Frith, ‘The role of metacognition in human social interactions,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2012, 367, 2213–2223. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3385688/

Etienne Gilson, The Unity of Philosophical Experience, Ignatius Press, [1937] 1964.

Herbert Gintis, Carel van Schaik, and Christopher Boehm, ‘Zoon Politikon: The Evolutionary Origins of Human Political Systems’, Current Anthropology, Volume 56, Number 3, June 2015, 327-353. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581024/

F. A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society,’ American Economic Review, Sep. 1945, XXXV, No. 4, 519-30. https://statisticaleconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/the_use_of_knowledge_in_society_-_hayek.pdf

Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, A Hunter-Gatherer’s Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life, Swift, 2021.

Erik P. Hoel, Larissa Albantakis, and Giulio Tononi, ‘Quantifying causal emergence shows that macro can beat micro,’ PNAS, December 3, 2013, vol. 110, no. 49, 19790–19795. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1314922110

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

D.N. McCloskey, ‘The Open Fields of England: Rent, Risk and the Rate of Interest, 1300-1815,’ in Galenson, D.W., (ed.) Markets in History: Economic Studies of the Past, Cambridge University Press, 1989, 5-51. https://www.deirdremccloskey.com/docs/pdf/Article_50.pdf

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell with Mind And Matter & Autobiographical Sketches, Cambridge University Press, [1944, 1958, 1992] 2013.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Yale University Press, 1998.

Michael Stevens, The Knowledge Machine: How an Unreasonable Idea Created Modern Science, Penguin, [2020] 2021.

Marx, in his theory of surplus value, held that it was parasitism—appropriation by the bourgeoisie of the product of labour. The Nazi and Communist mass murders both claimed to be eliminating malicious parasites from society: defined by race in the first and class in the second.

The Catholic Church, with canon law; Islamic religious scholars, with Sharia; and brahmins, with their rites, mediations and law (such as Manusmriti), provided their civilisations with an institutional commons that extended across jurisdictions. That Christianity did not ground law on revelation—even canon law was taken to be human-made and could be, and was, revised—turned out to be a key difference in the evolution of the respective civilisations.

I would just like to thank my commenters for some very thoughtful, and thought-provoking, comments.

Thanks for the illuminating overview. Linking Newtonian mechanics to Enlightenment mistakes that we still pay for -that’s something I’ll remember. But the analysis of the dichotomy between bio-rooted resilience and modern notions of efficiency - that’s even bigger. At 65 and retired I can look back and see the thread of that going way back, so it’s great to get such a coherent and compact elucidation even at this late date. I was a high school teacher and saw first hand how administrative bureaucrats, blind to their own biases and blinkered perception, were determined to satisfy managerial notions of efficiency under circumstances -particularly in inner-city schools - that were bound to frustrate. Glad that’s over but wish I’d read this awhile ago! Cheers!