The struggles of states, the contentions of classes

International politics and the West’s internal tensions.

US Naval College Professor S.C. “Sally” Paine provides an enlightening distinction between maritime order and continental anarchy as ways of ordering state systems that helps makes sense of the current world order.

The maritime order is based on positive-sum transactions where commercial efficiency is a powerful advantage. By contrast, zero- or even negative-sum resilience is the operative principle of continental anarchy [where the aim is to be stronger than your neighbours, even if you all end up with less].

Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine; Hamas’s vicious attack on Israel of October 7 2023; the Islamic Republic of Iran seeking to destabilise the Middle East in its own favour while surrounding Israel with violently hostile proxies; the much-feared possible CCP invasion of Taiwan—these all represent continental anarchy in operation. NATO and the EU represent—as does the US alliance structure in the Indo-Pacific and more broadly—attempts to institutionalise, expand, and defend the maritime order.

The Ukraine War is very much a clash between the maritime order Ukraine was edging towards and Putin’s continental anarchy geopolitics. As I noted in the earlier post, that Israel seeks support from the maritime order while operating in particularly vicious arena of continental anarchy creates a major informational war problem for it.

China provides a fascinating case, in that the CCP’s concerns for its own resilience creates a division between its continental anarchy approach and the interests of the Chinese people in positive-sum transactions. Meanwhile, class contentions within Western democracies provide much stronger parallels with those divisions in CCP-run China than it is comfortable to contemplate.

A serious vulnerability of the “rules-based international order”, as the maritime order is usually described, is that it has become caught up in the internal Western struggles between—to use social analyst David Goodhart’s differentiation—the transnationally-connected Anywheres and the locally-connected Somewheres and between the accountable (those whose income depends on their performance) and unaccountable (those who are paid for turning up) classes. The latter distinction is from journalist Richard Miniter’s perceptive analysis.

The unaccountable classes include most bureaucrats—whether in the public, non-profit or even much of the corporate sector—government employees and academics. The massive increase in bureaucratisation and higher education has hugely increased the size of the unaccountable classes, their claims on resources and their ability to mould public discourse. French political economist Thomas Piketty has tracked the effect the expansion in higher education has had on postwar politics across a range of Western democracies.

A fundamental difference between the maritime order and continental anarchy is the difference between positive-sum efficiency of the former and zero- or negative-sum resilience of the latter. A difference that operates not only between the maritime order and continental anarchy but also between the accountable and unaccountable classes, though there much of the problem is the West’s unaccountable classes undermining both efficiency and resilience.

The maritime order

The maritime order seeks to promote gains-from-trade—so positive-sum interactions—where commercial efficiency becomes a prime advantage as it builds a society’s income and wealth, so its capacities. Such efficiency enables you to release more resources into the realm of positive-sum, gains-from-trade transactions and so earn more income and build more wealth.

In many realms of human action, how incentives operate can depend powerfully on how they are framed. Such framings can vary dramatically between cultures.

Commerce is a very unusual human activity in that it has very strong feedbacks—do you gain or lose resources?—and is focused on a primal concern—gaining or losing resources. Hence it can have patterns that replicate across human societies far more than do many human activities.

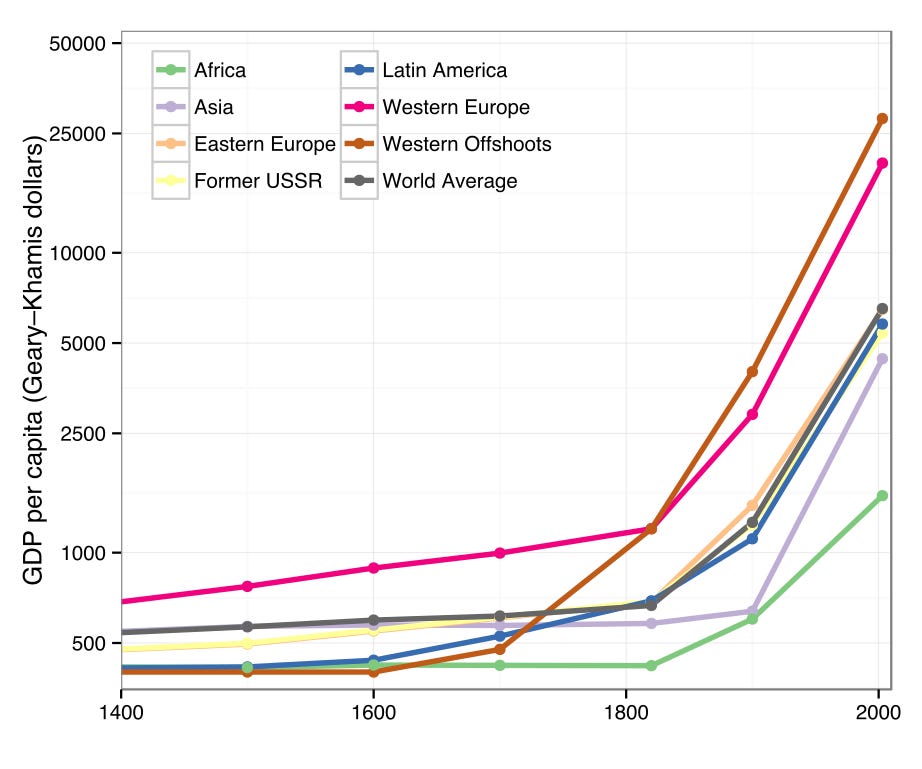

Innovation is primarily about such positive-sum efficiency; about expanding the ambit of such transactions, including greatly expanding what one can use as resources and how one can use resources. This expansion in the range and use of resources from technological advance is the story of the Great Enrichment, the massive increase in wealth and mass prosperity since the Industrial Revolution.

This shift to mass prosperity mostly began with the application of steam power to transport, via steamships and railways, in the 1820s. This created the first age of mass globalisation, which ended in 1914 with the outbreak of the Great War of 1914-1918—what I have sometimes call The Dynast’s War, as it was generated by dynastic regimes who proved unable to control the total war dynamics of the mass societies they were attempting to maintain their dominance of.

Prior to the 1820s, the two basic sources of state revenue were land and trade. Seizing land, seizing (and creating) trade hubs, incorporating them into your pacified territory, was the way to increase state revenue. As the Great Enrichment proceeded, promoting manufacturing and commerce became more and more the dominant path to increasing state revenue. This made the maritime order more and more dominant as a way to organise world affairs.

The first great period of globalisation—from the 1820s to 1914—relied on the pacification of the oceans by the Royal Navy. The second great period of globalisation—from 1945 onwards—relied on the pacification by the US Navy and its allied navies.

In the first period of globalisation, the Royal Navy’s capacity to pacify the oceans came from Britain’s economic power—both in manufacturing and in finances—plus its far-flung Empire that gave it bases around the world. In the second period of globalisation, the US Navy’s capacity to pacify the oceans relies on US economic power—both in manufacturing and in finances—married to an oceans-spanning alliance structure that gives it bases and allied navies around the world.

Continental anarchy

The realm of continental anarchy is about building the resilience of your state and regime—its ability to survive various shocks and change in circumstances—by expanding its territory and power and its ability to dominate those around it. You can win from negative-sum interactions—interactions where there is a net decrease in resources—provided they make you stronger than your neighbours.

This can be true even if both sides have less resources at the end of such interactions, if you are further ahead of your neighbour than you were when those interactions started. Though the danger then is that some third party might be in a position to move in. The most dramatic case of such being the Arab/Muslim break-out in the C7th after the Roman (“Byzantine”) and Sassanid Empires had spent over two decades fighting each other to a standstill. A problem made worse for the Sassanids as they followed up that war of mutual imperial exhaustion with civil war.

Mass prosperity through manufacturing and commerce—that both creates and uses an ever-expanding technological base—meant the retreat of continental anarchy as a mode of state interaction. As noted above, that retreat did not mean continental anarchy’s disappearance.

Hitler’s lebensraum was very much continental-anarchy thinking. So is Putin’s conception of Russkiy mir imperialism, based on spurious notions of state lineage and seeking to continue the long-running pattern of Russian autocracy of domination, incorporation and vassalage that the dominated, incorporated and former vassal countries bolt from as soon as they can. Since 1991, that bolting has included joining the institutional structure of the maritime order, through joining NATO and the EU.

About China

China—Zhongguo, the Middle Kingdom, the Central Realm—provides its own wrinkle on continental anarchy. Since 1949, the armed forces of the CCP have fought border wars with India (1962), the Soviet Union (1969), and Vietnam (1979). Wolf-warrior diplomacy sought to impose patterns of deference and domination on countries in its region. With the notable exception of the Qing-Romanov treaties, China has little past experience of dealing with peer states and its experience of such has mostly not been a positive one.

China’s internal experience of alternating bouts of disunity and unification has deeply affected Chinese outlooks.

The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.

The famous opening line of the C14th Romance of the Three Kingdoms is from the novel set in during and before the Three Kingdoms period from the collapse of the Han in 220 up to the brief Jin unification of China in 280 (that fell apart in 304). The retreat southwards of the Jin regime ushered a prolonged period of disunity, prior to the Sui unification of 589.

China as a civilisational space is bounded by the steppes to the North; deserts, mountains and the Tibetan plateau to the West; jungles to the South; and the East and South China Seas to the East. While the Central Plains (Zhongyuan) of the Yellow River valley is the heartland of Chinese civilisation, its core area extends to the Yangtze and Pearl River valleys. The Han heartland is essentially two large, and one smaller, river valleys, with the two larger river valleys being linked by the Grand Canal.

Being geographically circumscribed in this way meant that China never experienced any equivalent of the European Volkerwanderung or the migrations of peoples into or across the Middle East and Northern India. This has enabled the creation of a Han cultural unity—especially in elite culture—despite the persistence of local languages (“dialects”). A unity greatly helped by a shared writing system.

This geographically-circumscribed region based on irrigated farming has made unity a persistent pattern of Chinese history in a way that is absent from other civilisational regions. The Romans were the only state to unify the Mediterranean world; the Persian (550-330BC) and Caliphal (from the 630s to the 820s) unifications of the Middle East were exceptions to a normal disunity; northern Indian Empires were rarely able to more than briefly rule the South or even unify the North beyond the Ganges River plain; mainland Southeast Asia was never unified. Nor were these regions to ever achieve anything remotely resembling the coalescing of the Han ethnicity and cultural commonality.

The Han heartland has achieved densities and levels of population only rivalled by Northern India. Up to the early C19th, a unified China represented between a quarter and a third of humanity united under a single ruler. Using techniques of mass mobilisation developed during the Warring States period (C5th-C3rdBC), Chinese states fought wars on scales that no other civilisation would rival until the modern era.

Prolonged periods of peace led to significant population increases. Conversely, the collapse of unified rule—whether in rebellion, disintegration into warring states or pastoralist conquest—were demographic disasters on a scale only rivalled by mass pandemics, the Mongol conquests or the World Wars and totalitarian megacides of the C20th. The Chinese obsession with harmony and social order is an entirely rational response to their history.

None of these periods of divided rule were stable in any useful sense. Only successful unification brought stability. Either unification under a single ruler or the war and strife of continental anarchy were the only historical options. Why would we expect the Chinese state—especially an autocratic Chinese state—to operate on any other basis than continental anarchy, than resilience through dominance?

In Chinese history, harmony means unified rule at home and deferential neighbouring states abroad. The tributary relationships that were the standard Chinese model of international relations were far more about acceptance of Chinese primacy by neighbouring states than resource transfers.

This history helps explain why the CCP finds itself in this contradictory geopolitical situation. On one hand, it clearly sees itself as rightfully dominating its region, expecting deference from neighbouring states. Hence it resents the way the American alliance system allows regional states to limit such deference.

On the other hand, the commercial expansion of China since 1978 has turned China into the world’s largest trading nation, the greatest single beneficiary of the US-led maritime order. The CCP resents and resists a maritime order that the society it rules is the greatest beneficiary from.

The weaker its neighbours, the more the CCP can dominate them. The weaker its neighbours, the less they will buy from China. The interests of the CCP and the interests of the Chinese people do not coincide in these matters. The Chinese people do, however, have an interest in the continuation of a stable social peace.

The resilience of CCP rule requires its dominance over its own people. In terms of ability of Chinese people to organise, to pressure, to coordinate, the CCP seeks to repress the capacities of the Chinese people. This is resilience-of-rule-through-repression that sits uneasily on top of a dramatic, decades-long surge, in commercial, positive-sum, gains from trade—especially as the greater the level of positive-sum manufacturing and commerce, the more revenue (and so resources) available to the CCP.

Taiwan exemplifies the contradictions of the CCP regime.

On one hand, Taiwan, like Hong Kong, has been an enormously useful conduit and source for foreign investment in commercialising China. On the other hand, also like Hong Kong, Taiwan represents a liberalising mercantile society in deep tension with the resilience-of-rule-through-repression that CCP domination represents. This is made worse by Taiwan being an active democracy with its own armed forces.

Taiwan becomes both a threat and unfinished business from the Chinese Civil War, given that Taiwan was founded by the losers of the Civil War, who proceeded to do a patently much better job of encouraging human flourishing than did the CCP.

Those who take the liberal, positive-sum interactions of the maritime order as somehow natural persistently fail to grasp the logic of zero/negative-sum regime resilience that the patterns of continental anarchy represent. Patterns that were dominant—indeed the presumptive standard geopolitical mode of operation—throughout the history of human states (and before) and which still operate outside the maritime order.1

The post-1978 commercialisation of China was not begun by the CCP. It came “from below”—starting with spontaneous de-collectivisation of land by the peasants—which the CCP decided not to quash, but sought to manage for its own benefit.

It remains an open question whether the commercialisation of Chinese society is now permanently established or whether it will become NEP (New Economic Policy) Mark II: something that comes and goes. The way Xi Jinping has presided over a dramatic resurgence in the role of state-owned enterprises in the Chinese economy—and has worked to deepen CCP control of, well, everything—points to such a reversal being a real possibility.

Moreover, Marxist ideology is the most redolent version of the technocratic fallacy: the belief that human flourishing is a computational problem (“the administration of things”); that it is a matter of techne, knowledge how. Hence the Soviet delusion that technology could solve the problems of central planning.

The human brain is not a computer. We humans cognitively model significance, not facts, and significance is personal and varied. Nevertheless, it is a natural temptation of Marxist ideology to not only see commerce as wicked (“exploitive”) but dispensable. There is also a long history of the Chinese state being suspicious of anything beyond its own apparatus of rule that connects people across localities, including commerce.

China will continue to have a very large, highly educated, workforce for the next two decades. The labour-force potential for continuing Chinese economic growth is substantial.

Even assuming it does not strangle China’s commercial vitality, how well the CCP can navigate Chinese growth shifting from expanding infrastructure, factories and exports—based on technological catch-up—to growth from expanding domestic consumption, while being far more at the technological frontier, is also an open question. Especially given the debt burden, and the considerable waste, the system of centrally-directed financial repression has generated.

Geo-strategically, there is no China. China does not even have any armed forces. There is the CCP, which has armed forces recruited from within China and maintained by Chinese resources. The armed forces with which it conquered China.

A lot of what drives the CCP is its interests against the people of China. This is greatly complicated by China’s economic success providing the CCP with far more resources, yet commerce is inherently antithetical to CCP’s official Marxist-Leninist ideology. One of the ongoing issues is how much—and how fast—the CCP is intellectually and culturally Sinifying (Marxism is a Western import) and in what ways.

Yes, the people of China are beneficiaries from the positive-sum maritime order. An order that has a great deal to with their mass exit from poverty. The CCP, on the other hand, in its concern for its own resilience, operates according to the zero- or negative-sum dynamics of continental anarchy.

Meanwhile, in the West

So, the maritime order, it’s completely different from such autocratic continental anarchy right? Well, yes the positive-sum, gains-from-trade maritime order does represent a very different mode of interactions between states than continental anarchy. But when we look internally at contemporary Western democracies, the differences with the CCP dynamics are not as stark as many seem to believe.

There is a tension between mercantile positive-sum efficiency and current class dynamics within Western societies. For, within Western countries, there are negative/zero-sum institutional and class dynamics that are neither efficient not resilient for Western societies as a whole, but are very much effective as forms of social aggrandisement.

A model to keep in mind is cancer. Cancer represents cells defecting from cooperating with other cells in a body while propagating effectively within the body. Cancer can be both resilient yet fatal for the body it lives off.

The interests of the unaccountable classes within the West—bureaucrats, activists, academics, public sector workers, and so on—are to expand their authority and the flow of resources to them. This primarily rests on control of discourse, through controlling what is deemed legitimate or not. This means increasing bureaucratisation, increasing activism, propagation of their narratives of legitimacy and increasing censorship. Hence we see private-public partnerships being used to censor and to debank people, to cut them out of ordinary commerce and finance.

It is, for example, in their interests that AI operate in a way that supports their narratives of legitimacy. This is, of course, precisely how the CCP wants AI to operate regarding its narratives of legitimacy.

The Biden Administration using debanking to create an AI cartel makes perfect sense once one realises AI can be—and to a large degree already is—used in such a way. While the “African Nazi” problem from Google’s AI image generation provided an egregiously obvious case, the ability to produce more subtle (or not so subtle) distortions in AI responses is clear. This can come from internal algorithms and/or what material is sourced—either from in-built filters or the legacy of past patterns of online censorship, including self-censorship, or uneven patterns in readily available material.

Party-States, such as CCP China, are centralised networks of Party activists dominating the State and all other institutions while controlling discourse. This is the power of an unaccountable class in its most complete form.

The West does not have such democratic centralism. What it does have is networks of activism pushing in the same institutional and narrative-control domination by the unaccountable classes.

The convergence becomes even clearer if one looks at the history and intellectual origins of DEI (Diversity Equity Inclusion).

The first state to bring a DEI program was the Soviet Union, with its Korenizatsiya program. Mao developed his own version of DEI and notions of privileged/oppressor v oppressed groups (the so-called Black and Red identities). This was an improved version of the Soviet original. North Korea has its own version, the Songbun system. It is not remotely accidental that a lot of DEI training turns into struggle sessions.

When one looks at the—almost entirely spurious—intellectual underpinnings of DEI in the West, it comes from derivatives of Critical Theory, which are themselves derived from Marxism. All those DEI officers, intimacy consultants, sensitivity readers and so forth are the networked-activism equivalents of commissars, who are updated versions of inquisitors. The people who operate on the basis that error has no rights and they can determine error.

The fiscal burdens of Western welfare states are clearly undermining the fiscal resilience of Western states by driving up public debt. But the problem is much worse than that, as the apparatus of the welfare states—which includes both government bureaucracies and NGOs (non-government organisations)—gets more resources and authority the larger the scale of their operations. Those operations expand as social pathologies expand. The homelessness industrial complex very much operates on such a pattern.

Increasing resources and career opportunities from increased social pathologies is a disastrous—indeed, socially corrosive—incentive structure. As investor Charlie Munger famously said:

Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome.

If you have organisations whose incentive is to maintain and increase social pathologies, that is precisely how one must expect them to act. Especially as we Homo sapiens are very good at self-deceptively rationalising and moralising our self-interest. The apparatus of the welfare state must be expected to degrade both the fiscal and the social resilience of their state and society over time.

But it gets worse than that. To be of the unaccountable classes is to be insulated from feedback—that is, information with consequences—from how what they do affects the wider society. Meanwhile, what makes their networks more effective will be selected for. So, there will be selection for both conformity and for beliefs that support coordination within and across such networks.

The selection for conformity flows from them being networks. Network goods tend to be monopoly goods, as the larger the network, the greater the benefit from being in the network. The more conformity in belief there is, the more effectively the network will operate.

But this is conformity in belief within the network. Not across the wider society: on the contrary, coordination works better if there is selection for conformity within the network while also differentiating from those not in the network.

What works in such a way? Selection for beliefs that require greater and greater levels of rationalisation—and so signal commitment ever more strongly—while separating the rationalising believers from the wider society ever more successfully. This means selection for increasingly bizarre and toxic untruths—that require ever more rationalisations—so operate ever more successfully as signalling, loyalty and coordination and separation mechanisms.

Toxic untruths work for these networks because they are of the unaccountable classes, so those insulated from feedback about effects on the wider society. Conversely, the conformity pressures within the networks operate very strongly, as moral status through righteous belief requires the stigmatisation of unbelief. Academe has become more and more conformist, and more and more divorced from the views and concerns of the societies that pay for them, due to such dynamics.

There is no shortage of such toxic untruths:

A person with a penis can be a woman. There is no problem having someone who has gone through male puberty competing in women’s sport. The surgical and hormonal mutilation and sterilisation of minors for gender non-conforming behaviour represents care and compassion. Moralising racial differences is outrageous if you put whites on top but morally laudable if you put whites on the bottom. Words are violence, but silence is also violence. The lab-leak hypothesis was a racist conspiracy theory. Defunding the police would have no effect on homicide rates. A disease whose risks were overwhelmingly concentrated among the metabolically compromised demanded general lockdowns and closed schools. Jews are not indigenous to Israel, so can be treated as settler-colonialists, even when they are refugees from Muslim countries. Meanwhile, Arabs are indigenous to Palestine, despite arriving centuries later.

The signalling, coordination, and status pressures are so strong, they can operate in industries where there is at least some connection between performance and income if the pressure of shared status games from moral status from righteous beliefs—and hence stigmatisation of un-righteous beliefs—is sufficiently powerful to override that, at least in part. Grants provided via members of the unaccountable classes can very much reinforce this.

Marxism is the most dramatic example of the coordinating and differentiating effects of toxic-to-human-flourishing untruths. (This includes selection for those prepared to do what it takes to enforce deference to those toxic untruths.)

Marxism also distills the vicious arrogance of progressivism, whereby the imagined future—and its attendant so-sophisticated mountains of rationalised bullshit built on molehills of truth—is so wonderful that believers see themselves as a moral and intellectual elite. That imagined splendour also trashes any past human achievement, effort or heritage that fails to live up to the believers’ imagined wonders. Indeed, that imagined future—the moral and intellectual wonder in their heads—is so wonderful that any dissent can only be motivated by malice, ignorance, stupidity or psychological deformity while anyone silly enough to defend past heritage and history can be tagged with any sin (real or imagined) thereof.

The realm of the future acts as the realm of divine authority—there is no information from the future, so one is not constrained in one’s claims of authority therefrom. The claims on behalf of the “marginalised” become sacred—the realm from outside of which no trade-offs are accepted. This sacralisation seeks to exempt the claims on behalf of the sacred marginalised from ordinary politics, which are all about trade-offs, hence believers practice the non-electoral politics of institutional capture.

Meanwhile, everything about the existing society—the cultural heritage, the political heritage (e.g. the US Constitution), traditional family structures, and so on—are subject to de-sacralisation. The 1619 Project was all about de-sacralising—indeed, demonising—the political and cultural heritage of the US. The cognitive infrastructure of zealotry is constructed from the divine authority of the imagined future and the attendant patterns of sacralisation and demonisation.

Hence it is hardly surprising that it is derivatives from Marxism—via Critical Theory and its offshoots—that provide the basis for vicious arrogance exemplifying by online mobbing and cancel culture (i.e., purges without labour camps) in propagating coordinating toxic untruths in the contemporary West. This is another point of convergence with the CCP—remembering that things can converge without being identical.

Moreover, any “no-debate” claim must be presumptively regarded as false—well-founded cases do not require protection from debate—and a mechanism for networked domination. The claim that dissent represents moral or other deformity makes such “no-debate” claims much more plausible. (The Leninist version of this is “counter-revolutionary”.)

A significant amount of the employment of the unaccountable classes are in activities that impede commercial efficiency. The most dramatic—and socially destructive—manifestation of all these bad incentives is in destructive migration policies.

The rules-based international order is tied in with how the open society postwar consensus has evolved to include the advocacy and implementation of migration policies that are very much against the interests of the local working classes and of the social and fiscal resilience of Western societies. Such welfarist, DEI, mass migration, advocacy and policy networks are defecting from social solidarity—and from social cooperation—analogous to how cancer cells do.

As the editor of First Things, R.R.Reno observes of the world Western elites now preside over:

1:16:18: What kind of society have we created where the number one desire of ordinary people is to be protected? We’ve created a society where they're under assault all the time: economically, culturally, morally. They feel like everything is being torn apart: they have no home, they have no trustworthy place, they have no role.

A persistent failure of mainstream commentators on the stresses that Trump and other national populists are putting the rules-based international order under, is to completely fail to understand the class contention aspects of what is going on. Once you see those class tensions, you cannot un-see them.

Vice President J.D. Vance’s 14 February 2025 Munich Security Conference speech was formally about free speech and respecting the choices of the voters. It also expressed quite forcefully the class contention in Western democracies between elites who seek to control discourse, and determine whether voters’ choices at the ballot box are “legitimate” or not, and a broadening citizen—particularly working class—revolt against the same.

Such “technocratic” elites very much look to be in the business of converging with the CCP’s dynamics of rule, with its great firewall of China and social credit system. The EU seeing itself as a “regulatory superpower” is not only bad for the commercial efficiency of Europe, it becomes a mechanism for undermining freedom of speech, democratic choices and the social resilience of European societies.

One of the problems regarding support for Ukraine—apart from understandable fatigue with “forever wars”—is precisely to ask why Western elites who will not defend their own borders against influxes that are breaking-up working-class communities, increasing crime, displacing local people’s access to social service, suppressing their wages, and increasing fiscal burdens should be supported when they call for defending Ukraine’s borders. Western elites’s notions of moral legitimacy have increasingly become moral legitimacy against their fellow citizens. Hence the patterns of convergence with the CCP, such as the private-public partnerships being used to censor and to debank people, to cut them out of ordinary commerce and finance.

So, yes, the maritime order is absolutely superior to continental anarchy. But those who are presiding over the degradation of social order within Western countries—and undermining any sense of a resilient social contract with their own working classes—thereby become utterly compromised advocates for an international social order when they are doing such a toxically bad job of maintaining within their own societies a social order that respects and supports the citizens thereof.

References

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances,’ 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

George J. Borjas, We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative, W.W.Norton, 2016.

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Ben Cobley, The Tribe: The Liberal-Left and the System of Diversity, Societas essays in political & cultural criticism, Imprint Academic, 2018.

Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Pelican, 2018.

European Commission, Projecting The Net Fiscal Impact Of Immigration In The EU, EU Science Hub, 2020. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/projecting-net-fiscal-impact-immigration-eu_en

Harry Frankfurt, ‘On Bullshit,’ Raritan Quarterly Review, Fall 1986, Vol.6, No.2. https://raritanquarterly.rutgers.edu/issue-index/all-volumes-issues/volume-06/volume-06-number-2

David Friedman, ‘A Theory of the Size and Shape of Nations,’ Journal of Political Economy, Vol.85, No.1, Feb. 1977, 59-77. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24107762_A_Theory_of_the_Size_and_Shape_of_Nations

Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´inez-Toledana, Thomas Piketty, ‘Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right: Changing Political Cleavages In 21 Western Democracies, 1948–2020,’ The Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Vol. 137, 2022, Issue 1, 1-48. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/137/1/1/6383014

David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics, Penguin, 2017.

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Joe L. Kincheloe, Critical Constructivism, Peter Lang, [2005] 2008.

Eric Kaufmann, Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities, Penguin, 2018.

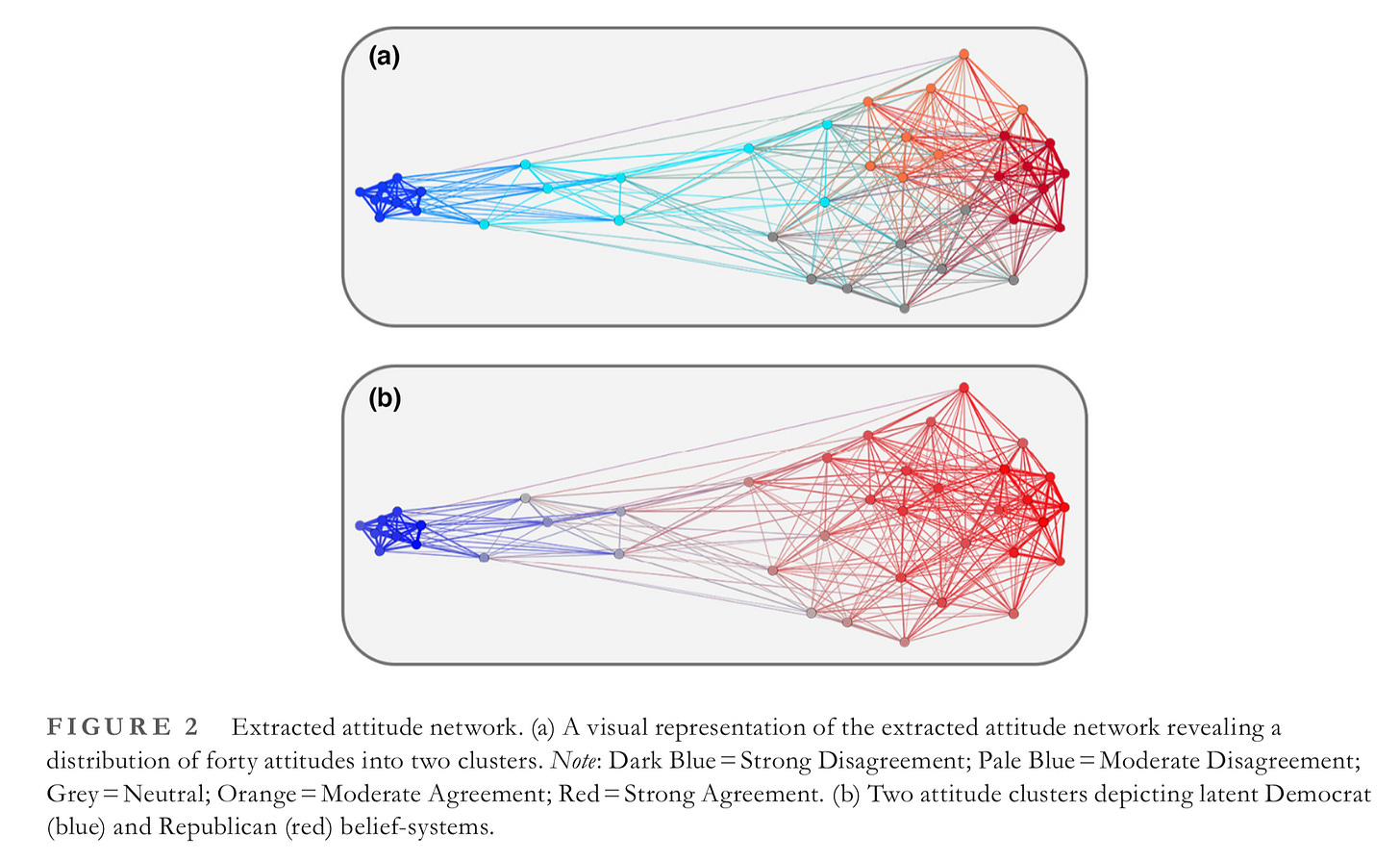

Adrian Lüders, Dino Carpentras, Michael Quayle, ‘Attitude networks as intergroup realities: Using network-modelling to research attitude-identity relationships in polarized political contexts,’ British Journal of Social Psychology, (2024) 63, 37–51. https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjso.12665

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Stephanie Muravchik, Jon A. Shields, Trump’s Democrats, Brookings Institution Press, 2020.

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Jordan B. Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

One of the problems is seeing states as “manifestations” of their societies when states are basic structuring elements of their societies.

This is one of the best things you've written, summing up many other articles as well providing new information. Well done.

Brilliant, as always.