In the shadow of the state (2)

The state structures society, it is not a reflection or product of society.

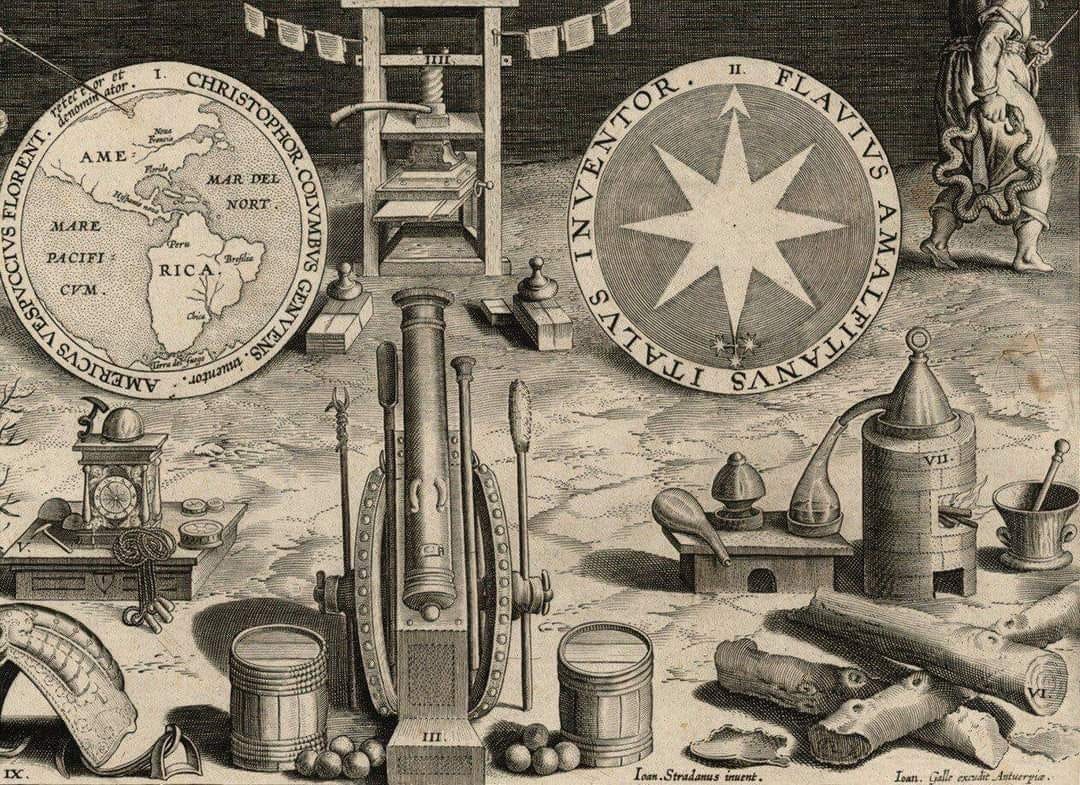

Gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press were the 3 great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society. Gunpowder blew up the knightly class, the compass discovered the world market and founded the colonies, and the printing press was the instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites.

Karl Marx, ‘Division of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery’ in Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, Part 3) Relative Surplus Value.

With this quote we can see what is wrong both with Marx’s notion of the role of technology in social causation and with a very common notion of the relationship between state and society.

The false—but very common—view of the relationship of state and society is that the state is a product of its society, that the state emanates from its society. This gets the dominant relationship almost entirely the wrong way around. It is far more true to say that the state is a fundamental structuring element of the social dynamics of the territory it rules rather than the reverse.

It is perhaps easiest to see this by noting the glaring flaw in Marx’s reasoning. The gunpowder, the compass and the printing press were all originally Chinese inventions. Indeed, Europe acquired—via intermediaries—gunpowder and the compass from China. (Gutenberg’s printing press appears to have been an independent invention.)

Yet, as Marx was very well aware, China did not develop a bourgeoisie in his sense. Indeed, Marx’s notion of the Asiatic mode of production grappled with precisely that lack.1

In 1620, Sir Francis Bacon wrote in his Instauratio magna that

…printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass... have altered the face and state of the world: first, in literary matters; second, in warfare; third, in navigation…

This was true of the effect of these inventions in European, but not Chinese, hands.

Why were these inventions globally transformative in European, but not Chinese hands? Because of the differences in the structure of European state(s) compared to the Chinese state.

Unified China …

The first difference is that the European states were states, plural. Europe had competitive jurisdictions, it had centuries of often intense inter-state conflict. From the Sui (re)unification (581) onwards China was, with brief interruptions, a single polity.2 What the evidence—both Chinese and Roman—shows quite clearly is that civilisational unity in a single polity is bad for institutional, technological and intellectual development.

The second difference is with the internal structure of European states compared to the Chinese state. The Sui dynasty, by introducing the Keju, the imperial examination—refining the use of appointment by exam that went back to the Warring States period—created a structure that directed Chinese human capital to the service of the Emperor.

There were three tiers of examinations (local, provincial, palace). You could sit for them as often as you wished. So a significant proportion of Chinese males devoted decades of their lives to attempting to pass the exams. Over time, the exams became more narrowly Confucian—probably because it required a high level of detailed mastery, so had more of a sorting effect—thereby promoting intellectual conformism.

The Chinese state became a structure that dominated its society, using kin-groups as social structuring mechanisms that enabled the state apparat to economise on its downward reach. There was a functional limit to how large the command-and-control state apparat could get if the Emperor was to have a reasonable degree of control of it. Hence the Chinese state fostered, rather than suppressed, kin-groups to economise on administrative effort. Though it did take steps—such as rotation of officials and barring them from serving their home county—to limit the degree that kin-groups colonised the structures of the state itself.

With the very limited exception of kin groups—or things that functioned as ersatz kin groups, such as tongs, triads and cults—there were simply no rival centres of social power to the state bureaucracy outside the apparat of the state. There was no military aristocracy; no self-governing cities; no armed mercantile elite; no organised religious structures beyond local temples—especially after Emperor Wuzong of Tang (r.840-846) effectively abolished monasticism.

Indeed, it is up for debate how much Imperial China had a society at all. Yes, there were families, and households, kin-groups, temples and commerce. There was social activity. There were even social dynamics. But, organisationally, Chinese society was very thin—apart from kin-groups and kin-group substitutes—especially once you got beyond the village level.

Villages did, however, quite a lot of things themselves, precisely because the state apparat stopped at the county level, with the county magistrate and his (small) staff. Law, and the apparatus of law, was under-developed in China precisely because the centralised, command-and-control state economised on administrative reach, so that other mechanisms of mediation and adjudication developed.

This state dominance of authority, and thinness of organised social structures, left an impact on how Chinese thought. In his fascinating study, The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline, Yasheng Huang observes:

The tenacity [of autocracy] is also rooted in the psychology of the citizens—in norms that axiomatically defer to authority and in an epistemology that views the world in terms of issues, events, and people rather than systems of incentives and constraints. (P.185)

It is a conspicuous feature of Chinese dramas (aka C-dramas) that the stories are all about getting the bad people out, and the good people in, so that all will be well.

The CCP’s suspicion of cults is well-grounded in Chinese history. Likely in part because of the organisational thinness of Chinese society, religious secret societies have been behind major social conflagrations that have killed millions of people and contributed to, or caused, dynastic collapse or withdrawal.

… and divided Europe

Conversely, when gunpowder, the compass and the printing press came to Europe, European states already had a military aristocracy; self-governing cities; an armed mercantile elite; organised religious structures; so a rich array of cooperative institutions. Moreover, kin-groups had been suppressed across manorial Europe, forcing—or giving the social space for—alternative mechanisms for social cooperation to evolve.34 In particular, due its self-governing cities with armed militias, medieval Europe had an (effectively) armed mercantile elites before gunpowder, the compass or printing reached Europe.

Alfonso IX of Leon and Galicia (r.1188-1230) first summoned the Cortes of Leon in 1188. This became the start of the first institutionalised use of merchant representatives in deliberative assemblies. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (r.1155-1190) had tried something similar earlier, but the mercantile elites of North Italy preferred de facto independence, defeating him at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

The first European reference to the compass is in a text written some time between 1187 and 1202, with its use appearing to expand over the 1200s. The first reference to gunpowder in Europe is not until 1267 and it took centuries before gunpowder played a major role in European warfare.

Both the compass and gunpowder really only have transformative effects from the late C15th onwards, which is also when the printing press is spreading across Latin Europe. By that time, medieval Europe has already become a machine culture and it had been for centuries the civilisation with the most powerful mercantile elite. A reality driven by competitive jurisdictions, a rural-based military aristocracy, law that was not based on revelation (so it could entrench social bargains), suppression of kin-groups, and self-governing cities.

Competition between European states was a powerful driver of the transformative use of technologies. But so was the level of striving within such states: adventurers able to mobilise resources—and seeking wealth, power, prestige—had far more room to operate (and receive official sanction) in Europe than in China.

In other words, the differences in the development and use of technology—and in social dynamics and formations—between China and medieval Europe was fundamentally driven by the differences in state structures, in how the relevant polities worked.

Marx’s story of technological social causation is flatly wrong. It is much more the other way: social structures enabled, or not, technological capacities, which then have implications for social structures.

While knighthood in the medieval sense did not survive mass gunpowder warfare, what had been the knightly class transitioned into the gentry and aristocracy of Europe, dominating the officer class of the new royal armies. This could extend to raising army units themselves. The winged hussars of Poland, arguably the most unreasonably successful heavy cavalry in history—regularly winning battles against the odds—were not even much of a transition.

Japan also

Japan provides a particularly clear example of the importance of a different evolution for a state. Early on, the Yamato state adopted the notion from China that the Emperor owned all the land in the Taika Reforms of 645. It even (briefly) adopted the Keju. But Japan’s state structure evolved in a very different direction to China’s. One that, to a large degree, ended up being a convergent evolution with that of Latin Europe.

Japan did not have self-governing cities nor merchant representatives in institutionalised deliberative bodies. It did have a rural-based warrior elite, competitive internal jurisdictions, prosperous merchants with vigorous commerce, significant religious establishments, and political bargaining, both among and with elites who had their own power centres.

Japan at the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868 looked much like Europe in 1468. Hence Japan’s ability to “fast forward” European history so as to catch up with the West in a few decades.

Japan ended up with a political structure, in the lead-up to the Pacific War, that looked very like that of Second Reich Germany in the lead up to 1914-1918. It came a-cropper in much the same way.

Which society?

Another very large difficulty with the “state emanates from society” claim is: which society? The borders of states waxed and waned, expanded and contracted. What is the territorial extent of the “society” from which the state is supposed to have emanated?

Moreover, the first states developed in very specific localities. States typically arose in seasonal-crop river valleys, as the stored food (and seeds) of seasonal crops meant a more intense protection problem and generated the potential tax base required for chiefdoms and states.5

The state is both protector and predator, with the balance between the two shifting over time and between states.

Most of the territories of the globe first had a state imposed on them from outside. Even when a state originally developed locally, a territory and people could end up being ruled by a state imposed from outside.

Egypt was definitely a place where state(s) originated. Nevertheless, between the flight of Pharoah Nectanebo II from the Achaemenid Persians in 340BC to the Free Officers’ Revolt in 1952, Egypt was ruled by foreign dynasties and empires. For over two millennia, there was a state in Egypt, but there was no Egyptian state.

To a large degree, what constitutes a society is precisely what is incorporated within the shared institutional commons the state creates. By institutional commons I mean:

interacting institutions within a territory, where conflicts have default arbitrators (such as rulers or courts) and rules with remedies (law).

Civilisations with law arbitrated by religious scholars—typically based on revelation—could have a civilisational-wide institutional commons, as was the case in Islam and Brahmin civilisation.6

An institution is:

any complex social form that reproduces itself, such as legal systems. So, sets of rules and supporting norms used by a population to organise repeated activities.

Public goods have a scope problem: who is to be taxed/charged? for whom are such goods to be provided? Public and private providers of public goods typically come to the same solution—to bundle them with territory, effectively turning the public good(s) into a club good. An institutional commons is created out of public goods being bundled together so that they have common coverage.

Interactions

Yes, there is clearly interaction between the state and society within the territory it rules. This is particularly clear in the dynamics of Chinese dynastic cycles:

Population expands due to peace and prosperity, this pushes against resources (mainly arable land), creating mass immiseration, peasant revolts and falling state revenues.

Elite aspirants expand but elite positions do not, leading to disgruntled would-be elites who provide organising capacity for peasant revolts.

Bureaucratic pathologies multiply, leading to a more corrupt and less responsive and functional state apparatus, eroding state capacity and increasing pathocracy (rule by the morally disordered).

These processes culminate in regime (and state) collapse. In China, the process usually took around three centuries, with the full cycle showing up under the Tang (618-909), Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. The Song dynasty (960-1279) never entirely unified China, so is a more complicated case.

Highly bureaucratised government tends to undermine the resilience of society.

Western states have been insulated from such patterns of state collapse, at least since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire: not coincidentally, a highly bureaucratised state. Wessex (519-927)7 to England (927-1707) to Great Britain (1707-1801) to the United Kingdom (1802-present) has a continuous state history. It is punctuated by the 1066 Norman Conquest, various civil wars, and the 1688 Glorious Revolution, but there is not the sort of state-and-regime collapse that punctuates Chinese history. Both William I in 1066 and William III in 1688 insisted that their invading army was supporting the rightful succession within a continuing state.

There are other states with very long continuous histories that also do not have Chinese style regime-and-state collapses. Certainly not as regular patterns. While the origins of the Japanese state are disputed, it dates from at least 538. France is a unified state from c.509, Denmark from c.936, the Kingdom of Leon and the Kingdom of Galicia existed from 910 to 1833 when they became part of a unified Spain, and so on.

Since the adoption of Chinese-style meritocratic bureaucracy, Western states are beginning of show signs of analogous patterns to the Chinese dynastic cycle. Having experienced the early-dynastic patterns of effective government based on capable, meritocratic bureaucracy, there are now increasing signs of dysfunction coming from the increase in state (and other) bureaucracy beyond the scale and scope that existing mechanisms of accountability can cope with.

As well, the combination of regulation restricting the supply and use of land for housing plus mass migration is driving up rents and housing prices in a way that is immiserating large parts of the local working, and even middle, class.

The massive over-expansion of universities is degrading the return from higher education and gives new graduates powerful incentive to dispossess older cohorts in the institutions they enter: the purity cycles of Critical Constructivism (aka “wokery”) are very useful for this.

The expanded bureaucracies have evolved—as bureaucracies are so wont to do—increasingly pathologically.

A modern version of the Chinese dynastic cycle is in play, though how it will play out is much less clear.

We can, however, clearly see the creation of socially insular networks of decision-makers. Folk who have clearly adopted or evolved mechanisms for blocking grappling with facts and concerns inconvenient for their own identity and (highly moralised) sense of status, operating inside media silos.

Part of the problem comes from separation, scale and complexity of organisations. Especially when combined with insulation from feedback and intensification of groupthink. If one’s sense of identity and status rests on not-noticing, then a whole lot of not-noticing can occur.

Many of the problems of contemporary democracies come from the evolution of a range of mechanisms to evade accountability. Mechanisms that include using international bodies to launder—typically terrible—ideas so as to give them a spurious sense of authority. The more bureaucracy itself becomes the problem—yet democratic politicians rely on using the levers of bureaucracy to govern and deliver policy—the more broken accountability is likely to be.

Precisely because states are not emanations of their society, it is a continuing struggle to ensure the apparatus of the state is responsive to, and serves, the wider society. There is no final victory where accountability wins forever.

References

Mikael S. Adolphson, The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan, University of Hawaii Press, 2000.

Alberto Alesina, Paola Giuliano, ‘Family Ties and Political Participation,’ Journal of the European Economic Association, Volume 9, Issue 5, 1 October 2011, 817–839. https://docs.iza.org/dp4150.pdf

Philip Bobbitt, The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History, Anchor, 2003.

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Jean Gimpel, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages, Pimlico, [1976] 1992.

Avner Greif, Guido Tabellini, ‘The clan and the corporation: Sustaining cooperation in China and Europe,’ Journal of Comparative Economics, Volume 45, Issue 1, 2017, 1-35. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0147596716300981

Yasheng Huang, The Rise and Fall of the East: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline, Yale University Press, 2023.

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021). https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/alternative-theoretical-framework-economics.

Timur Kuran, The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/workingpapers/2016/twerp_1129_moav.pdf.

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144. https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/153953/.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

Yascha Mounk and Roberto Foa, ‘The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect,’ Journal of Democracy, vol. 27, no. 3, July 2016, 5-17. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/the-danger-of-deconsolidation-the-democratic-disconnect/

Joel Mokyr and John V.C. Nye, ‘Distributional Coalitions, the Industrial Revolution, and the Origins of Economic Growth in Britain,’ Southern Economic Journal, (2007), 74: 50-70. https://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/jmokyr/Charleston-Olson-8.PDF

Robert Neuwirth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation and Social Rigidities, Yale University Press, 1982.

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, [1990] 2011.

James C. Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Yale University Press, 2017.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Yuhua Wang, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Mark S. Weiner, The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom, Picador, 2014.

Xueguang Zhou, The Logic of Governance in China: An Organizational Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Marx was not an honest intellectual reasoner:

As to the Delhi affair, it seems to me that the English ought to begin their retreat as soon as the rainy season has set in in real earnest. Being obliged for the present to hold the fort for you as the Tribune’s military correspondent I have taken it upon myself to put this forward. NB, on the supposition that the reports to date have been true. It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way.

Marx to Engels, [London,] 15 August 1857, (emphasis in the original).

The Song (960-1279) failed to fully unify China, but they were the only significant Han polity. That the Song were effectively within a mini-state system does seem to have affected their policies, including the unusually—for a Chinese imperial dynasty—strong focus on trade and technological development.

Kin-groups had already been suppressed in the city-states of the Classical world, including Rome. They re-emerged with the incoming Germanic peoples, and then were suppressed again by the Church and the manorial elite, remaining in the agro-pastoralist Celtic fringe and Balkan uplands.

Economists Avner Greif and Guido Tabellini define clan (i.e. kin-group) as “a kin-based organization consisting of patrilineal households that trace their origin to a (self-proclaimed) common male ancestor.” They contrast this with a corporation: “a voluntary association between unrelated individuals established to pursue common interests”. They note they perform similar functions: “they sustained cooperation among members, regulated interactions with non-members, provided local public or club goods, and coordinated interactions with the market and with the state”. Triads, tongs and cults can also perform these functions.

Pastoralists also generated states, but more as super-chiefdoms operating as lineage confederacies than as states with layers of officials

Economist Timur Kuran has explored how Sharia—law based on revelation—inhibited the ability of Islam to deal with the Western challenge. The British imposition of common law on India—replacing Brahmin law—enabled India to have full-range political bargains that can then be entrenched in law. India, like the Classical Mediterranean and Mesoamerica, had a tradition of non-autocratic polities. They succumbed to various empires—particularly the Mauryan (322-185BC)—as, without the representative principle, such polities could not scale up as well as could autocracies. The development of Brahmin law based on revelation, as a response to Buddhism and the other sramana movements, meant such polities did not re-appear, as not being able to entrench political bargains in law made such politics not worth the costs.

Or 886 if we count from Alfred the Great (r.871-899) declaring himself King of the Anglo-Saxons. Æthelstan (r.924-939) was the first King to declare himself King of the English (Rex Anglorum) in 927. Rex Angliae (King of England) did not fully replace it as the royal title until John (r.1199-1216).

Marx is wrong, but isn't it amazing how plausibly it reads? It's one of those "simple, neat and wrong" situations.

These are all excellent points LW, however… the dynastic cycles 3 traps which we are most definitely fallen into in America are tied to and superimposed by DC. They’re also funded by DC.

Which means if anything happens to DC and something is happening… those 3 tornadoes are loosed.

The entire meritocratic system is an Imperial One imposed upon the American Federation- which America is and has been since the Iroquois Confederation.

One might well say it’s DC Imperial Forces vs American 🇺🇸 Federation Forces.

I don’t fancy their Map, I mean the Red/Blue county map. Rather grim if it comes to blows.

Trump is certainly sending his Team of Vengeance, Gabbard, Gaetz, Ratcliffe all have suffered injury and lawless abuse at the hands of those they now command, and Hegseth * is a combat veteran, which means he intensely dislikes the Pentagon and probably most Generals.

The ranks don’t care for their Generals or Admirals.

In fact hissing isn’t considered bad form and no Officer will correct you.

*Hegseth may not be known abroad or in Elite circles but he’s well known and respected by veterans.