What is Hamas?

The trouble with fighting networks.

Son of Hamas, the memoir of a son of one of the founders of Hamas, was originally published in 2010. I bought, and read, the expanded version that came out in 2011.

After the recent horrors in Israel, I re-read it. As the life story of the son of a founder of Hamas — so in a sense a Hamas Prince — who grew up in the West Bank under Israeli occupation, became an informer for Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, and converted to Christianity, it is a highly readable ripping yarn of a memoir.

The book is also very revealing about social dynamics and the background to events. What was it like to grow up a Palestinian under Israeli occupation? Oppressive. What was it like to grew up in an environment of endemic political violence? Worse.

What was it like to grow up in a family where your father was greatly respected but also was regularly imprisoned — usually by the Israelis, but also by the Palestinian Authority? A wild roller-coaster, where there was much respect when his father — a revered imam, and the son of a respected imam — was around but then having to endure the poverty from the family’s abandonment by the community when his father was imprisoned, as he frequently was.

The book is also very revealing of how poor much of the Western reporting on the Middle East — and Israel-Palestine — is. Western reporting regularly shows little understanding of Islamic culture and institutions and fails to look seriously at the incentive structures. Very secular Westerners are at a particular disadvantage trying to understand deeply religious sensibilities.

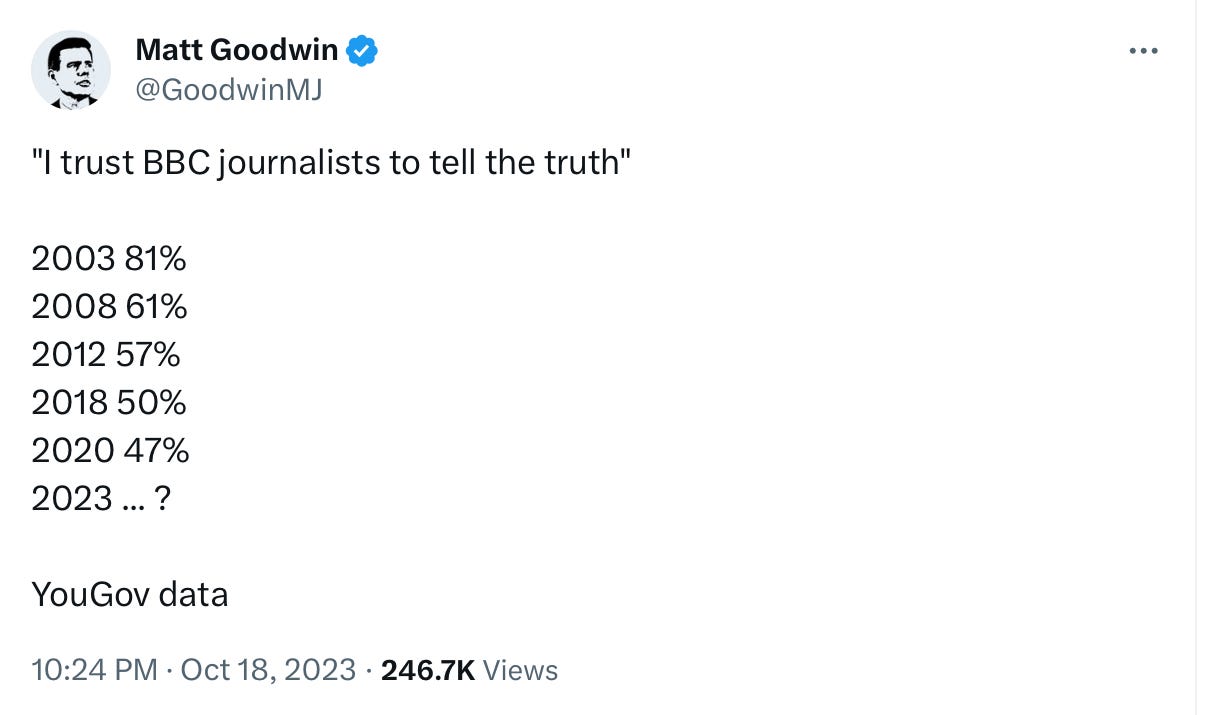

Then again, it is clear that much “quality” Western media is remarkably poor at understanding, and reporting on, their own societies. Why would they be any better at reporting on very different societies? The mainstream media’s retreat into readily available framings that seek to flatter both those propagating them, and those accepting them, makes things worse.

The BBC’s travails over refusing to call Hamas — an organisation officially classified as a terrorist organisation across the Western world and much of the Middle East — as terrorist and its killers, as they kill, often horribly, civilians en masse, terrorists expresses this retreat into congenial framings. Framings that are self-flattering within particular social bubbles but are further burning the BBC’s already falling credibility outside those bubbles.

There are also issues about manipulation of online information. Such manipulation can have intensified effect where it coincides with framings pushed in mainstream media and in universities: with the former often coming from the latter.1

While reading Son of Hamas, it becomes clear that Israeli security services — though unusually efficient — still run into Seeing Like A State problems. The territories and people they are trying to control are not legible to the state in a way that the state needs them to be.

That Israeli security services seem to have been completely taken by surprise by the — clearly well-planned and prepared — attacks on October 7, 2023 was an extreme manifestation of an endemic problem.

It also becomes clear that to think of Hamas as a highly structured organisation is a mistake. It is more like a connected series of networks. Surveying the situation in the years 2003-2006, Mosab Hassan Yousef writes:

…the Hamas military wing consisted of only about ten people who operated independently, had their own budgets, and never met together unless it was urgent. (p.211)

Later, with the original Hamas leadership dead or in gaol, it becomes increasingly a mystery who was actually coordinating Hamas (p.216). It turned out to be very “secular” looking men who worked at the Al-Buraq Center for Islamic Studies (pp220-1).

Revelation as law

Middle Eastern society still very much operates via kin groups. A prisoner who lacks kin is easily bullied by others. Conversely, of a prominent figure in the PLO, Mosab writes:

Al-Natsheh was from the largest family in the territories, so he feared nothing (p.150).

Islam and Brahmin civilisation both developed law based on revelation with religious scholars as mediators and judges. Both developed institutional structures that were civilisation-wide, rather than based on individual states. Both civilisations were ruled by autocracies that came and went, generally leaving remarkably little institutional trace behind them.

Brahmin civilisation was a riverine farming civilisation, subject to waves of invasion by pastoralist peoples. Islam was a highly expansionist civilisation based on sanctifying the pastoralist synthesis of polygyny, patrilineal kin-groups, raiding and enslaving non-believing outsiders, law based on revelation and high levels of cousin marriage.

British rule socialised India into common law and Parliamentarianism. In part, because there was a long history of resistance to Brahmin dominance.

All the Sramana movements — the most notable of which were Buddhism and Jainism — represented resistance to Brahmin social dominance. What we call Hinduism was the Brahmins adapting (successfully) to the Sramana challenge. Even within contemporary Hindutva, Hindu nationalism, there is no serious agitation to bring back Brahmin law.

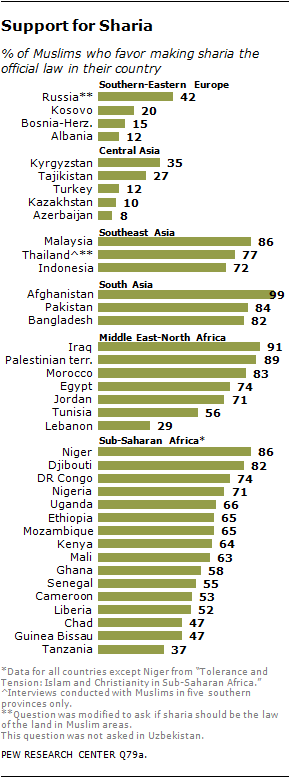

In Islam, by contrast, there is a great deal of support for maintaining the dominance of Sharia. Middle Eastern North African (MENA) Islam, with its very strong kin-groups and long history of slave warrior autocracies — the advantage of slaves being they had no local kin groups, their only local connection was their master — has proved resistant to democracy and Parliamentarianism. Much more so than (pdf) non-MENA Islam.

Kin-group societies find it relatively easy to develop what are, in effect, substitute kin groups, going back to the ritual societies that anthropologists have found across pre-state societies. The tong and triads of Chinese society and diasporas; the jati of Brahmin civilisation; the tariqa (Sufi orders) of Islam, can all operate as substitute kin groups or as mechanisms for generating mutually supporting kin groups.

It is common for a tariqa to have a clan at its core that provides its leaders.2 Muslim religious leadership has frequently been clan based. In Saudi Arabia, while the al-Saud provide the political leadership, religious leadership has been dominated by the al-ash-Sheikh, the descendants of Muhammad ibn Adb al-Wahhab (1703-1792), founder of Wahhabism.

As tariqa come in both militant and non-militant versions, modern jihadi organisations are, to a significant degree, updates of an already existing pattern within Islam. Given that mainstream Sunni Islam is a religion of dominion — it is supposed to be seeking universal submission to the rules of Allah, the sovereign of the universe3 — it is easy to see why militant Islam is associated with so much violence, including organised violence. It is a modern development of deeply embedded institutional patterns.

Toxic networks

As one reads Son of Hamas, and reads or listens to other sources, such as the excellent Conflicted podcast, it becomes clear that Israel specifically — and the Middle East more generally — is suffering from a violent version of what is also plaguing Western societies. That is, the problem of toxic networks. The problem of viral networks that operate as toxic parasites, evolving to infect weaknesses in their host societies and the institutions thereof.

In the period from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, the prime organisational weapon for undoing political orders was the centrally-directed political Party. Bolsheviks, Fascists, and Nazis, all perfected the ability to combine political mobilisation, institutional penetration and violent action via a centrally-organised political Party.

With the increasing development of mass transport and communication — accelerated by IT and social media — and expanding bureaucratisation, the totalitarian political impulse has shifted to mobilising via networks.

In Islam, these networks are overtly religious, pushing the politics of salvation. The 1979 Iranian Revolution showed the power of motivated networks. The cultural revolution currently afflicting Western societies — particularly the Anglosphere — is very much network-driven.

In the Western societies, these networks are implicitly religious, pushing the salvationist politics of the transformational future.4 Both mindsets are driven by folk with that mixture of the search for purity, underlying anger, and fear of loss of control,5 that leads to dangerously self-righteous, controlling, politics.

The key question becomes: how to disrupt the creation, sustaining and replicating of such networks? This includes how to make institutions far more resistant to them.

As we wait for the much-anticipated Israeli ground invasion of Gaza — which has the stated aim of destroying Hamas — the question becomes: if one is dealing with, not a centrally organised Party on the Leninist/Fascist/Nazi model, but a set of self-replicating networks, can a ground invasion destroy such networks?

Clearly, the physical capacities of Hamas can be degraded, and its leaders present in Gaza can be killed or captured. But if nothing else changes in Gaza, will the networks not just replicate once again? Especially as their funding overwhelmingly comes from outside Gaza.

One of the themes that is quite clear in Son of Hamas is how much Palestinians — and particularly their leaders — are paid to, in effect, never make peace with Israel. To the extent that Mosab Hassan Yousef states (p.132) that the Second Intifada was being planned before Arafat went to Camp David to negotiate with Israeli PM Ehud Barak:

Yassir Arafat had grown extraordinarily wealthy as the international symbol of victimhood. He wasn’t about the surrender that status and take on the responsibility of actually building a functioning society. So he insisted that all the refugees be permitted to return to the lands they had owned prior to 1967—a condition he was confident Israel would not accept.

Though Arafat’s rejection of Barak’s offer constituted a historic catastrophe for his people, the Palestinian leader returned to his hardline supporter as a hero who had thumbed his nose at the president of the United States, as someone who had not backed down and settled for less, as a leader who stood tough against the entire world (p.126).

For Arafat, there always seemed to be more to gain if Palestinians were bleeding (p.127).

Can Israel destroy the rule of Hamas in Gaza? Can it hand it over to the Palestinian Authority (PA)? Would the PA accept it from Israel?

It is entirely understandable that Israel has decided it cannot leave Hamas in power in Gaza. Dislodging it from power may, however, be harder than it looks. Destroying Hamas is likely to be harder still. Hence the importance of the question: not who is Hamas, but what is Hamas?

References

Lisa Blaydes, Eric Chaney, ‘The Feudal Revolution and Europe’s Rise: Political Divergence of the Christian West and the Muslim World before 1500 CE,’ American Political Science Review, February 2013.

Eric Chaney, ‘Democratic Change in the Arab World, Past and Present,’ Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, vol. 43(1) (Spring 2012), 363-414.

Eric Chaney, ‘Separation of Powers and the Medieval Roots of Institutional Divergence between Europe and the Islamic Middle East,’ in Masahiko Aoki & Timur Kuran & Gérard Roland (eds.), Institutions and Comparative Economic Development, chapter 6, 116-127, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Eric Chaney, ‘Islam and Political Structure in Historical Perspective,’ in Melani Cammett & Pauline Jones (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies,’ Chapter 2, 33-51, Oxford University Press, 2020.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like A State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Yale University Press, 1998.

Philip Selznick, The Organizational Weapon: A Study of Bolshevik Strategy and Tactics, Quid Pro Books, [1952, 1960] 2014.

Mosab Hassan Yousef with Ron Brackin, Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue and Unthinkable Choices, Saltriver (Tyndale House), [2010] 2011.

Folk—who are allegedly so concerned about Nazis—cheering on Islamic Einsatzgruppen with body cams has revealed how instrumental, so spurious, such anti-fascist posturing is.

This is the aim of Hamas, as a Sunni religious movement engaged in political action. Peace with Israel is obviously incompatible with that aim.

The imagined, transformational future acts as the realm of trumping authority from which there is no feedback (there being no information from the future), so operates as the divine in such politics.

As their “oppression” both expresses and justifies the (divine) authority of the transformational future, marginalised groups become sacred victims. As the sacred is the realm within which trade-offs are rejected, or massively resisted, and as, in this world of structure, we live in a reality of trade-offs, any ameliorative solution — especially if it involves changes in the behaviour of the group in question — is likely to be judged an offence against their sacred status (e.g., “blaming the victim”).

The fear of loss of control is why the practitioners of such politics often focus on matters sexual, as a way of controlling disturbingly chaotic erotic urges.

Thanks, nuanced take. I don't know enough to judge the sources. Yousef's take on Arafat seems a little too tidy a narrative for US, Israel. I defer to Chomsky (the man did read a lot) but despite the corruption of Arafat, I'm open to the idea that it was also a deliberately unpalatable proposal from Israels side. The way I see it it's 3D chess by hawks on both sides.

On another example of kinship networks and dysfunctional institutions, see Eric Stetson's book on the toxic family squabbles of Baha'i leaders (late 1800s, to about WW1). The more pro-unitarian (anti-authoritarian, liberal-secular, western) faction, the majority, was marginalized (more or less ex-communicated) by Abdul-Baha, who defended his claim to being the legitimate hereditary leader. Stetson's material shows the inherent authoritarianism and patriarchal nature of kinship group leadership, even in a "reformist" offshoot of Shi'ism that claimed to be seeking "harmony" of spiritual and modern-rational, scientific perspectives. In reality, the authoritarians set in motion a series of events that led to a long decline into increasing fundamentalism. Weirdly, as a persecuted minority religion in Iran, Bahaism became more fundamentalist under the post-revolution national govt of the mullas. (also see Juan Cole's critiques of Bahaism).