Why we should stop listening to economists on immigration

Unless and until they start analysing immigration like they do monetary policy: that it can be done well, badly, or disastrously.

If economists were intellectually serious about immigration, they would analyse it like they do monetary policy. Monetary policy can be done well; it can be done badly; it can be done disastrously.

Badly done monetary policy includes chronic inflation and stagflation—where both inflation and unemployment are high. Disastrous monetary policy includes hyperinflation—the Zimbabwean hyperinflation being a spectacular example—or some debt-deflation disaster, as in the 1930s Great Depression.

Monetary policy can be done well. Keeping expectations about the value in goods-and-services of money stable, and—directly or indirectly—expectations about the (positive) growth of spending in the economy stable, is good monetary policy. That produces the Great Moderation. Australia, from “the recession we had to have” until the pandemic shock was an example of such monetary policy.

If an economist said “monetary policy is good” or “I favour monetary policy”, they would be rightly regarded as saying something pretty silly, as how monetary policy is done matters so greatly. Yet as sensible an economic commentator as Noah Smith thinks it fine to say “immigration is good” and as perceptive an economist as Scott Sumner thinks he has said something sensible when he says “I favor immigration”.

The fact they think these are sensible statements to make tells us exactly how economists get immigration wrong. These statements treat immigrants as if they are a homogeneous, economically positive, group in all the ways that analytically count—including the implicit claim that the economic effects are all that matter and are reliably positive. That immigration is so wonderful that the net marginal benefits reliably exceed net marginal costs over all the ranges across which immigration happens and across all immigrant groups. That immigrants are the only Homo sapiens in human history who can’t make things worse.

You may claim to be agnostic at the optimal level of immigration, but even that implies it is just a level problem, not a content problem.

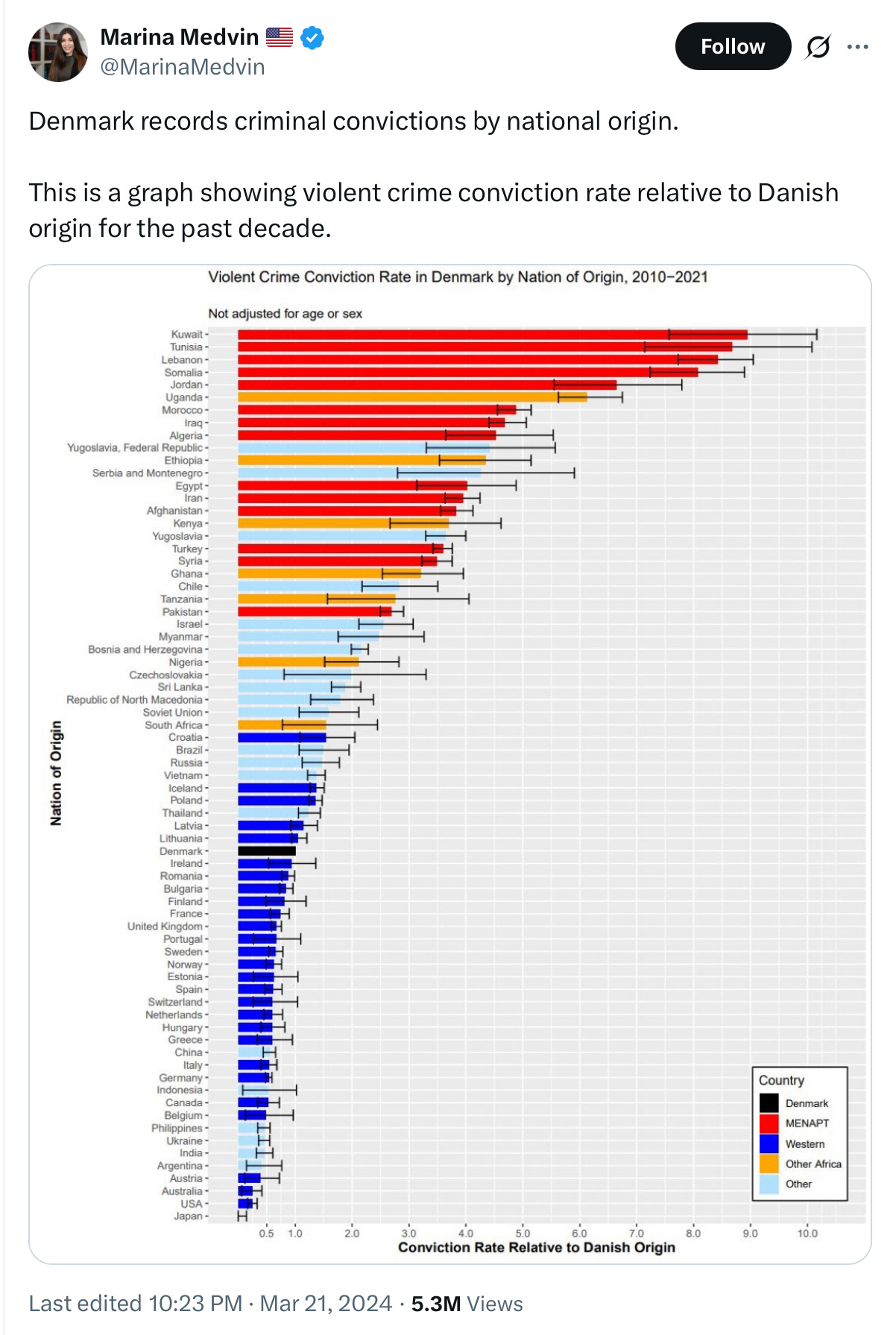

Given that the negative effects of mass immigration include fracturing countries along existing fault-lines leading to civil war—in the US in the 1860s; in Jordan and Lebanon in the 1970s—and mass rape of underage girls (Britain’s problem with “grooming gangs”), this is a deeply silly way to think of immigrants. (Actually, it is an offensively historically illiterate way to think about immigration.)

Immigrants are people. People vary in all sorts of ways that matter for the flourishing of human societies. They also vary quite dramatically in ways that affect how sustainable a liberal society is. People can make things worse.

Neither the costs nor the benefits of immigration are evenly distributed across recipient societies. If one talks of immigration as if it is reliably positive, that not only massively discounts discussion of its costs, it particularly discounts the claims of anyone who suffers disproportionately from the costs of immigration. As that is very much the resident working class—a group whose views and experiences economists rarely have to grapple with, and who they have social-status reasons to discount—this effect is not accidental.

Now, if you think the only things that vary between societies are institutions and policies—that we humans are otherwise interchangeable widgets, so people moving from countries with worse institutions to better ones is unproblematically a net gain—then treating immigrants as if they are interchangeable widgets may make a certain superficial sense. It takes astonishing historical ignorance to think in this way, but if you are the right sort of Theory-fool, it makes a certain superficial sense.

A Theory-fool is my term for what Adam Smith calls a man of system:

The man of system, on the contrary, is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it.

He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it. If those two principles coincide and act in the same direction, the game of human society will go on easily and harmoniously, and is very likely to be happy and successful. If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder. Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).

Yet treating immigrants as interchangeable widgets—to be analysed as if countries are analytically arenas for transactions where efficiency is what counts above all—does not make all that much sense, even in its own terms. If immigrants change the balance of labour and capital in a society, that matters. The level of capital—including skills, i.e. human capital—that immigrants bring with them matters even more if you are running a welfare state that transfers income from high-income folk to low-income folk.

People can make things worse

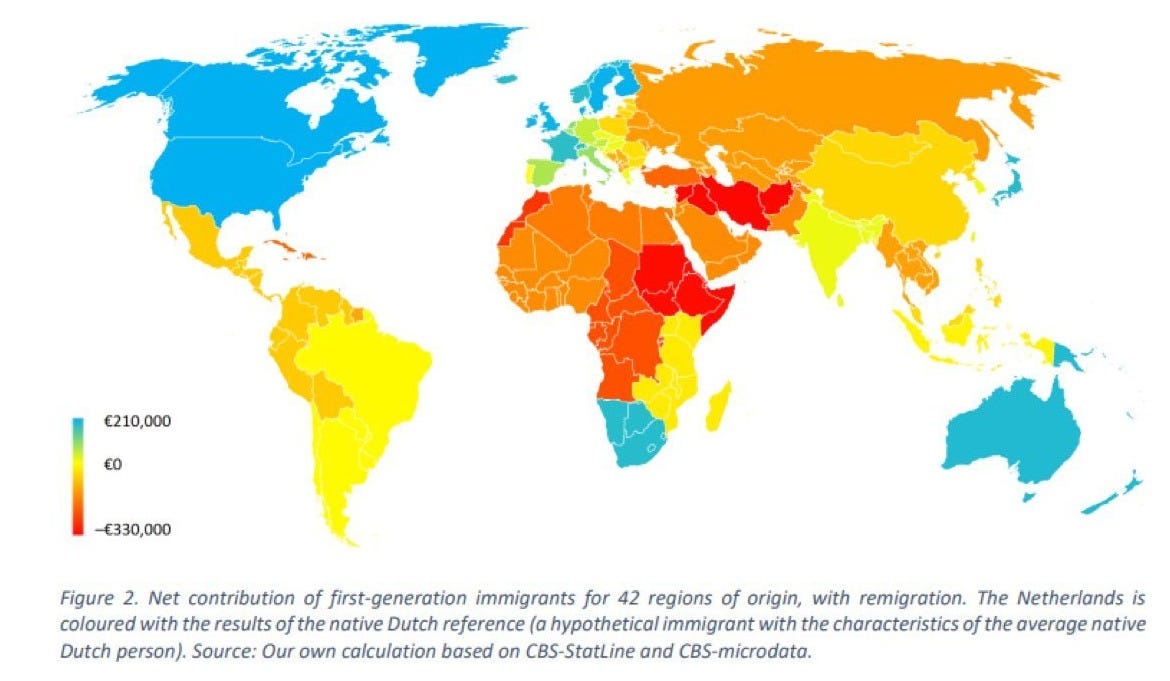

If you are running a welfare state, then importing low-skill immigrants will put increased pressure on the fisc. Importing large numbers of low-skill immigrants then makes one’s welfare state less financially sustainable over time, as copious evidence from Europe is now demonstrating. (Europe is famously 12 per cent of world population, 25 per cent of world GDP and 60 per cent of world welfare spending: of course the impact of immigration on welfare states matters.) This is aggravated if immigrants come from populations that have been marrying their cousins for centuries, driving up their rates of birth defects, increasing their sickliness and so driving up health costs.

But the comments by Noah Smith and Scott Sumner demonstrate something else that is quite conspicuous—how mainstream American commentary on immigration ignores European experience and the European debates over immigration. This is not a pattern one sees elsewhere. In Japan, for instance, the Western European experience of immigration is very much seen as something to avoid. Ignoring the European experience of immigration seems to be a very American arrogance.

Even more basically, the claim that the only things that vary between societies are institutions and policies—that we humans are otherwise interchangeable widgets—is flatly wrong. Any commentary that treats immigrants as homogeneous in all the ways that count is either intellectually negligent foolishness or disingenuous charlatanism.

First of all, relying on institutions to generate convergent behaviour in Western societies requires that their rules and norms are enforced. One of the deep dysfunctions in the contemporary West—particularly in Anglo-America—is that elites are not sufficiently enforcing those institutional rules and norms. This is from a mixture of cowardice, political patronage games, and morally performative deference to favoured (“marginalised”) groups shading into outright subversion of those norms and rules (e.g. “decolonisation”), due to how elite status games have evolved, as I discuss in this review of Musa al-Gharbi’s mostly excellent book.

Indeed, mass immigration can—and increasingly is—setting up downward spirals. The need for immigrant votes encourages politicians not to enforce the norms and rules of institutions in ways that the loudest voices in the immigrant communities speak against. The failure to so enforce the norms and rules then degrades the operation of those institutions. The more immigrants from such sources one gets, the stronger the effect becomes. Minnesota is currently providing an object lesson in this pattern, but you can see it across much of Western Europe. This pattern of moving away from the same rules for all is why UK PM Sir Keir Starmer is known as Two-Tier Keir.

The most appalling example of this—and the most egregious example of “Broken Britain”—has been the serial failure to enforce basic laws, due to “anti-racism”, interacting with Islam’s legitimation of rape, thereby creating a Muslim “grooming gang” problem across multiple decades. Conversely, Australia crushed its local problem by the simple expedient of enforcing its laws. See Louise Perry’s excellent discussion below.

This corrosion of local norms and institutions is absolutely a pattern that is strongest among and from Muslim immigrants. So, Muslim immigrants come to the West to get away from the social dysfunctions of their own countries. Then, due to a mixture of familiarity, religious commitment, Western political convenience and cultural cowardice, the same patterns that made their original countries dysfunctional are increasingly replicated in their new countries. Any public noticing of this pattern, let alone attempt to do anything about it, gets denounced by the normal patterns of moral abuse—racist!, xenophobic!, Islamophobic!

Formal and informal censorship mechanisms are then brought in to punish and deter citizens from publicly noticing any of this. So, the citizens find their institutions being debauched, their authority to speak attacked and their public discourse degraded.

But immigration, it can’t be done badly, it’s just inherently good. I am sorry, why the f#@k do we listen to economists when they talk such f#@k-witted nonsense as immigration is just naturally good? As if immigrants are these saintly folk who can never screw things up? Unlike every other set of Homo sapiens under the sun.

Civil wars, mass rapes, degradation of institutions: we can observe these consequences of mass immigration. Why pay any attention to these Theory-fools that cannot do the elementary thing of analysing immigration like they analyse monetary policy?

It’s the culture, stupid

The bit that is missing from “all folk need to do is move from bad institutions to good ones” is, of course, culture. Analysing culture has had an awful record in the social sciences. There are an enormous number of definitions of culture. People regularly use culture as analytical silly-putty—they define and analyse culture to fit whatever hole in their analysis is required to be filled.

I used to be enormously sceptical about culture as an analytical concern for precisely these reasons. Then I read Kenneth Pollack’s PhD dissertation on Arab military effectiveness, and my analytical world changed. The work of Glenn Loury, James C. Scott, Joseph Henrich, Garret Jones; Jordan Peterson noting that we humans cognitively model significance not facts; all added to taking culture seriously.

Trying to find things that only humans do compared to any other species is surprisingly hard. Finding things we do at orders of magnitude greater levels than any other species is easy.

One thing that we humans do way better than any other species is non-kin cooperation. Medieval Christendom took that advantage, put it on steroids, and came—as Western civilisation—to dominate the planet from doing so.

Due to our incredibly biologically expensive children—it takes almost 20 years to train a forager child to garner as many nutrients as they consume—all humans societies transfer risks away from child-rearing and resources to child-rearing. We organise doing these things via culture.

Yes, cultures generate institutions, but our organisation of our societies to so cooperate starts with culture. That need to organise pervasive patterns of cooperation is why we have both culture and institutions.

Both culture and institutions operate to deal with collective action problems. We are the cultural species par excellence because we are the non-kin cooperation species par excellence.

Institutions are the systematic operation of norms and rules. We can think of families as informal institutions but the reality is we grow up immersed in culture far more than any formal institutions. There are reasons that parents in all cultures are nervous about peer groups.

Moreover, as I have noted repeatedly, we cannot neatly separate culture and incentives precisely because we humans cognitively model significance not facts. Culture is what gives us shared maps of meaning, shared patterns of significance. It is hugely easier to organise and maintain institutions when participants share patterns of significance, and so share norms and expectations.

It has become more and more obvious that how organisations and institutions work—or not—depends greatly on the culture of those interacting within, and without, the institution. Families and kin-networks operate as intermediaries between the same. The Roman Republic, the Greek city-states, the Papacy, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches; medieval Christian rulers; the knightly and noble class; everyone who ran a medieval manor; all participated in the systematic suppression of kin-groups in the Classical Mediterranean, Medieval European and Early Modern European worlds for good reason—to destroy an alternative source of authority and social action.

Rulers come and go. The kin-group is forever. This became not so in the Graeco-Roman Classical World, then European Christendom, as kin-groups were suppressed. This suppression created far more individualistic cultures than the human norm. (Kin-groups held out in the non-manorial, agro-pastoral Celtic fringe and the Balkan uplands, until they didn’t.)

Culture is built on the after-birth mechanisms for transferring information; but cultures also shape that information, they shape what is transferred and how. They are shared maps of meaning; shared patterns of significance; plus the bundles of life strategies that go with the same.

Yes, people can (and do) move between cultures. Yes, cultures evolve. But, just as we are not accidentally or incidentally social beings, we are not accidentally or incidentally cultural ones. On the contrary, the two march together. As a Darwinian psychologist with Jungian predilections says:

Now, being is not the same thing as objective reality. Being is what you experience as a conscious creature. That’s being.

Culture profoundly affects how you view and experience the world. Not in some robotic way, but in a pervasive way—especially when it is reinforced within your social networks.

Liberal universalism is itself predicated on an individualism that is the product of a particular cultural and civilisational matrix and is not remotely a universal perspective among humans. Western liberals are so often unable to see how specific to Western cultures the individualistic maps of significance through which they experience and view the world are.

As the scholarship has made increasingly clear, people from different cultures will react differently to the same circumstances. That is because, cognitively, they are not the same circumstances.

This means that people from different cultures—so with different maps of meaning, different patterns of significance—will react differently to institutions. This is why, what superficially look like the same institutions perform so differently in different cultural landscapes.

Hence we end up with patterns such as the correlation between how collectivist cultures are and how corrupt states are being 0.91. (Somali culture is, of course, highly collectivist and clan-based.)

This is why it is so important for high-functioning societies to insist that the norms and rules of their institutions are enforced. But that takes a strong level of cultural confidence. It does not happen in a period of cultural collapse.

What does cultural collapse looks like? When Western elites fail to enforce the norms and rules of our institutions and cultural heritage is no longer transmitted, but rather is actively debauched, subverted and “decolonised”. A cultural collapse that makes mass immigration way more costly as both cause and effect. Indeed, as we have noted, mass immigration spirals up the corrosive effects, as mass immigration puts those norms and rules under more and more pressure, and immigrants are more and more used as excuses not to enforce the norms and rules of the institutions, that make Western countries attractive places to come in the first place.

This pattern of cultural collapse; when the norms and rules of institutions are no longer enforced; when cultural heritage is not only no longer transmitted but is actively debauched; is what we can observe across the Western world. This is a pattern of cultural collapse largely arising out of our toxically incompetent (to put it “positively”), or deliberately destructive (to put it more negatively), universities.

As said universities are increasingly dominated by a Critical Theory magisterium that explicitly aims at the systematic subversion and replacement of Western culture, institutions and civilisation, the original intent of the core ideas is to be so destructive. What has given them far more reach is the transmutation of ideas from Critical Theory and its derivatives (Critical Race Theory, Critical Pedagogy, Queer Theory, Post-Colonial Theory, Settler-Colonial Theory, etc.) into elite status signals, into elite cognitive assets—what you have to affirm to be a good person; to be of the moral elite.

More and more, the West, particularly Anglo-America, suffers from skin-suit institutions. Institutions that no longer do, or no longer do well, what it says on the tin they are supposed to do, but nevertheless garner resources, and insist on respect, as if they were still doing what they are supposed to be doing. This includes mainstream media that sells narratives of “this is what good people, informed people, believe” resulting in selectively curated information flows, so information siloes and “bubbles”.

Doing mass immigration badly includes fracturing countries along their fault-lines that extend to civil war; serious political fracturing along provincial/metropolitan and generational divides; mass rape, increasing crime in various localities; degrading institutions … Mass immigration can be done really badly. Any analytically serious approach to immigration would grapple with how badly mass immigration can be done.

The trouble is, so many economists are not analytically serious about immigration. They are performing “skin suit” economics. They engage in the superficial forms of economic analysis—and demand respect for doing so—while refusing to get into the meat of the subject. Because, of course, the meat of the subject leads to inconvenient places.

Such places are inconvenient in a social sense. One is clearly Not A Serious Person, Not A Serious Economist, unless you repeat mantras such as immigration is good and you favour immigration.

Limits of mainstream Economics

It is, however, also inconvenient in an analytical sense. To analyse immigration seriously you have to go to places that demonstrate, very clearly, the limits of Samuelsonian “social physics” Economics.

That one can walk into any shop, market or bazaar anywhere across the planet and the same conventions of property operate, is a realm of astonishing commonality in human behaviour. That the loss-gain-risk pressures of commerce are so powerful leads to more commonalities in human behaviour. This enables economists to identify, and make robust predictions of general tendency, in these realms of human action.

Similar pressures operate in, say, military affairs: but only up to a point. It is easily possible to have cultural patterns that get in the way of being military effective. When the British, for example, identified martial and non-martial “races” (i.e., ethnicities) they were observing something real.

Military analyst S.C. “Sally” Paine explains why so much of what seems baffling about Japanese military and strategic behaviour in the Pacific War makes far more sense if you look at Japan’s military culture.

Kenneth Pollack identified features of Arab culture that get in the way of effectiveness in modern conventional warfare because of huge difficulties dealing with the fluidity of modern warfare. A striking example of this was the Toyota War, where the combined forces of mighty Chad—using machine guns on top of Toyota pick-up trucks—crushingly defeated Libyan forces lavishly equipped with every Soviet military item they could purchase.

On the other hand, set-piece defence and attack that they were well-drilled in, Arab forces can absolutely do. See the highly effective Egyptian attack on the IDF’s Suez Canal defences in 1973 or the series of set-piece Iraqi offences against Iranian positions in the late stage of the Iran-Iraq War, or the Iraqi Army’s step-by-step reconquest of Mosul from ISIS.

Being good at set-piece operations and bad at fluid operations in conventional warfare flows quite directly from features of Arab culture. It is how well-trained, well-equipped British and American tank forces—whose armies had not fought any tank battles since the 1950s—could crush Iraqi tank forces in 1991 that had defeated Iran on the battlefield a few years previously. Arab militaries have the same formal institutional structures as do armies around the world, but they operate differently due to cultural reasons.

So, culture matters. The more differences in maps of meaning, in patterns of significance matter, the more culture matters.

Hence the success of mainstream Economics in dealing with the gain-loss-risk patterns of commerce, and similar resource use, is so hugely misleading. Since immigration affects every aspect of the functioning of societies—so every aspect of where and how culture matters—immigration seems to be amenable to conventional “social physics” “economic particles” economic analysis, but is so not.

In fact, it is profoundly an area requiring cultural analysis and cultural politics. As conventional centre-right politicians across the Western world have—again and again—proved to be incompetent at cultural politics, it is mass immigration that is leading them to be pushed aside by national populists. It is why country-club Republicans got Trumped; Gaullists got Le Penned; Forza Italia got Melonied; Tories are getting Faraged; and now the Australian Liberals are getting Hansoned.

It is working-class voters who tend to lead the revolt, as it is their locality-based social capital that gets diluted and swamped by newcomers. It is their rents that get driven up. It is their localities, and access to infrastructure and government resources, that get swamped. It is their localities that have crime rates surge.

But modern economists do not have to grapple with such issues, nor talk to the people who do. On the contrary, they can get their social jollies looking down on such benighted folk from their lofty moral and cognitive heights on top of their Empires of Theory. After all, these people vote for Trump/Le Pen/Meloni/Farage/Hanson, they must be awful. Besides, GDP goes up.

A splendid example of economists being socially-positioning Theory-fools is this paper, whose authors include a future Nobel memorial Laureate in Economics. When you read the paper it is obvious that those quoted therein are complaining about the dilution and loss of their locality-based social capital—social capital as a term appears nowhere in the paper.

The authors of the paper entirely fail to notice this, as the paper does not have the analytical humility to see how things look to its largely working-class subjects, it is about positioning the authors as Very Serious People, who are Very Serious Economists, who can look down on the cognitively and morally benighted working class folk from their Heights of Theory. The authors clearly engage in the necessary level of self-deception to do so. Such self-deception we Homo sapiens are very good at. Contemporary Western academics have brought such moralising self-deception to a peak of perfection.

Mainstream economists have not strangely lost credibility among national populists and other alienated folk, they have pissed their credibility away with their incompetently narrow—and ridiculously Panglossian—takes on immigration. This is the sharp end of a wider over-rating within mainstream Economics of efficiency and under-rating of resilience—the ability to navigate changes in circumstances—even in its Theory-acceptable form of “risk management”.

Hence economists talking as if societies are just free-floating arenas for transacting individuals and firms where maximising efficiency is all we need worry about, not any social cohesion nonsense. If US corporate employers import Africans so they do not have to hire African-Americans, or Indians so they do not have to train Americans, that is just fine. Why do we worry about this citizen silliness anyway?

A large reason why conventional centre-right politicians have proved to be so hopeless at cultural politics—and so have been supplanted by national populists—is precisely because they bought the delusions of economists that immigration was just an economic issue and the economists could tell them what’s what.

No it isn’t and no they can’t.

Mainstream economists then whine about this shift, taking absolutely no responsibility for their role in it. The problem was not that conventional centre-right politicians did not listen to economists, it is that they did.

This analysing-culture-incompetence of too much of mainstream Economics, coupled with immigration becoming something with such strong social desirability bias—after all, we cannot possibly agree that the Western working class might have a point, or several points—is why economists do not analyse immigration as if it was monetary policy: as something that can be done well, badly or disastrously.

It is also why economists should be ignored on matters immigration unless and until they do. Until they stop with the skin-suit economics, and start looking at the entire picture, not just what their Theory tells them to look at. But serial analytical incompetence—provided one plays the correct academic status games—works across so much of contemporary Western academe, why should economists be any different?

ADDENDUM: The Lotus Eater boys discuss the horrors of mass rape across decades as a cost of mass immigration and the callous malfeasance of so much of the managerialist British state. The effects of mass immigration are not some theoretical exercise, they are what happens given the people imported and given how the state actually performs.

References

Robert P. Abelson, ‘Beliefs Are Like Possessions,’ Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 16, 3 October 1986, 223-250. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1986.tb00078.x

M. Ajaz, N. Ali, G. Randhawa, ‘UK Pakistani views on the adverse health risks associated with consanguineous marriages,’ Journal of Community Genetics, 2015;6(4):331-342. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4567984/

Plamen Akaliyski, Vivian L. Vignoles, Christian Welzel, & Michael Minkov, ‘Individualism–collectivism: Reconstructing Hofstede’s dimension of cultural differences,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2025). Advance online publication. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398587882_Individualism-Collectivism_Reconstructing_Hofstede’s_Dimension_of_Cultural_Differences

Alberto Alesina and Paola Giuliano, ‘Culture and Institutions,’ Journal of Economic Literature, 2015, 53(4), 898–944. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.53.4.898

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Prey: Immigration, Islam, and the Erosion of Women’s Rights, HarperCollins, 2021.

Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, Richard Davis, ‘Sacred Barriers to Conflict Resolution,’ Science, Vol. 317, 24 August 2007, 1039-1040. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1144241

Roy F. Baumeister, Is There Anything Good About Men?: How Cultures Flourish by Exploiting Men, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Jan van den Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, ‘Borderless Welfare State - The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances,’ 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371951423_Borderless_Welfare_State_-_The_Consequences_of_Immigration_for_Public_Finances

Jan van de Beek, Joop Hartog, Gerrit Kreffer, Hans Roodenburg, The Long-Term Fiscal Impact of Immigrants in the Netherlands, Differentiated by Motive, Source Region and Generation, IZA DP No. 17569, December 2024. https://docs.iza.org/dp17569

Abdulbari Bener, Ramzi R. Mohammad, ‘Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population,’ The Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 18 (2017) 315–320. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110863017300174

Joyce F. Benenson with Henry Markovits, Warriors and Worriers: the Survival of the Sexes, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

George Borjas, ‘Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature,’ Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013. https://cis.org/Report/Immigration-and-American-Worker

George J. Borjas, We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative, W.W.Norton, 2016.

Maarten Boudry, ‘A Spiral of Silence: How Academia Enforces Orthodoxy,’ Maarten Boudry’s Substack, Jan. 31, 2026.

David Card, Christian Dustmann and Ian Preston, ‘Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities,’ Norface Migration Discussion Paper No. 2012-13, February 2012. https://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/immigration-wages-compositional-amenities.pdf

European Commission, Projecting The Net Fiscal Impact Of Immigration In The EU, EU Science Hub, 2020. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/projecting-net-fiscal-impact-immigration-eu_en

Jean Ensminger (ed.), Joseph Henrich (ed.), Experimenting with Social Norms: Fairness and Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective, Russell Sage Foundation, 2014.

Mohd Fareed and Mohammad Afzal, ‘Genetics of consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease,’ Annals Of Human Biology, 2017 Vol. 44, No. 2, 99–107. https://www.academia.edu/33934871/Genetics_of_consanguinity_and_inbreeding_in_health_and_disease

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989] 1994.

Musa al-Gharbi, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, Princeton University Press, 2024.

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties,’ American Journal of Sociology, Vol.78, No.6, (May 1973), 1360-1380. https://snap.stanford.edu/class/cs224w-readings/granovetter73weakties.pdf

Mark S. Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

James Hankins, ‘Why I’m Leaving Harvard,’ Compact Magazine, December 29, 2025. https://www.compactmag.com/article/why-im-leaving-harvard/

M.F. Hansen, M.L. Schultz-Nielsen,& T. Tranæs, ‘The fiscal impact of immigration to welfare states of the Scandinavian type,’ Journal of Population Economics 30, 925–952 (2017), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00148-017-0636-1

Joseph Henrich, The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, Penguin, 2020.

Joseph Henrich, The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter, Princeton University Press, 2015.

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Hillard Kaplan, Jane Lancaster & Arthur Robson, ‘Embodied Capital and the Evolutionary Economics of the Human Life Span’, in Carey, James R. and Shripad Tuljapurkar (eds.), Life Span: Evolutionary, Ecological, and Demographic Perspectives, Supplement to Population and Development Review, vol. 29, 2003, Population Council, 152-182. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/46603844/Embodied_Capital_and_the_Evolutionary_Ec20160618-27827-pd0oin-libre.pdf

Robert L. Kelly, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum, Cambridge University Press, [1995] 2013.

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021). https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/alternative-theoretical-framework-economics

Timur Kuran, Private Truths, Public Lives: The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification, Harvard University Press, [1995] 1997.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Peter McLoughlin, Easy Meat: Inside Britain’s Grooming Gang Scandal, New English Review Press, 2016.

Keri Leigh Merritt, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

Tommaso Nannicini, Andrea Stella, Guido Tabellini, and Ugo Troiano, ‘Social Capital and Political Accountability,’ American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2013, 5 (2): 222–50. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.5.2.222

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Jonathan F. Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan P. Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich, ‘The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation.’ Science 366, no. 6466 (2019): eaau5141. https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~drkelly/SchulzHenrichetalTheChurchIntensiveKinshipGlobaPsychologicalVariation2019.pdf

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland South-East Asia, Yale University Press, 2009.

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Polygamy, the Commodification of Women, and Underdevelopment,’ Social Science History (2021), 46(1):1-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354584406_Polygamy_the_Commodification_of_Women_and_Underdevelopment

Thomas Sowell, Knowledge and Decisions, Basic Books, [1980] 1996.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Robert Trivers, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, Basic Books, [2011] 2013.

Mark S. Weiner, The Rule of the Clan: What an Ancient Form of Social Organization Reveals About the Future of Individual Freedom, Picador, 2014.

Outstanding analysis and pulling together the strings of though into a coherent position as always.

We really need to start a nice big new university just so we can put Lorenzo in charge of it.

I also think the coining of the term Theory-Fool is a piece of genius.

Everything.