De-mystifying money

The Money Multiplier does not exist and other obfustications of monetary jargon.

Economists disagree greatly over money and monetary policy: what money is, how monetary policy operates. They do not even agree on a common analytical language.

Unfortunately, money is treated as requiring a special language plus analysis separate from conventional supply and demand. The notion of the “real” economy—the economy abstracted away from money—manifests this quarantining off of money.

Starting analysis of money with money being a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value means that analysis starts with separating money from standard supply-and-demand analysis. Let us, instead, look at why money exists, at what money fundamentally does.

At its simplest, money is what you use to transact more easily with people you have no other connection with. Money minimises the required information. You do not have to search for something specific the other transactor wants, you just pay in money.

Money starts with commodities used as an exchange good—something you hold to exchange for (other) goods and services. The following have all been used as money:

Beads (whether made of stone, shell, glass or whatever), beeswax, buffaloes, camphor, cattle, cloth (from silk to wadmal, a coarse wool fabric), coca leaves, cocoa beans, coconuts, strings of coconut discs, dye cakes, feather coils, gold dust, weighted gold, grain (notably barley and rice), human heads, logwood (mahogany), tool metals (iron, copper, tin, bronze) in various shapes, plaited palm-fibre rings, pigs, porcelain jars, balls of rubber, salt (including stamped salt cakes), seeds, shells (especially cowries), silver in lumps or shaped, animal skins, slaves, carved stone (a tool material), tea (including in bricks), teeth, tobacco.

The list was compiled from A. Hingston Quiggin’s 1949 monograph, A Survey of Primitive Money. This is a list of commodity money—something used as money that has other uses. But coins or notes that are tokens—that only have value because of their branding as money—are also exchange goods. Indeed, that is all they are.1

So, money is an exchange good: something you use and hold to exchange for other goods and services. The price of money is what you can get in exchange for it, what we can call its goods-and-services-value or output-value.2

A money allows you to transact readily with folk you have no other connection with. Thus, using money means that the economy—as measured by the number and scale of transactions—is larger than it otherwise would be.

Precisely because money has an economic function, and is an (exchange) good, we cannot expect money to be neutral in its effects on the wider economy. It is not an economic epiphenomenon that can be abstracted away from with no other consequences, at least in the short run.

On the other hand—beyond enabling a (much) higher level of transactions than there would otherwise be—money’s information-economising, transaction-facilitating functions may well have less and less differential effect across longer time frames. The evidence does suggest that the long-term neutrality of money on the economy—i.e. if all the money prices changed by the same percent, the rest of the economy would proceed on unchanged—is a reasonable analytical heuristic.

Money being an exchange good that you can use in the current time period means that it is also an asset that can be held for future use. The ability of money to be both an (exchange) good and an asset makes it something of a hinge between the output economy and the asset economy.3

That money can be an asset, can be held for future use, means that Say’s Law—production creates demand—does not work across a single time period. Folk can be paid in money. They can then sit on that money, so you can get a general glut of (other) goods and services—what we call a recession.

Such a glut of goods and services means that transactions to purchase those goods and services are not happening. Another way to think of recessions and depressions is a significant, sustained, fall in transactions.

Money held for future use may or may not also be a liability for someone. If money is simply coined bullion (gold or silver), it is not a liability for anyone. If it is notes exchangeable for bullion, it is a liability for whoever is promising the swap the bullion for the notes. If it is notes exchangeable by the monetary authority for other notes (so token or fiat money), it is not a liability in any binding sense. Hence the tendency of fiat money to having falling output-value over time—what we call inflation.

Since money can be used as payment, it can be used to buy goods or services, to buy assets or denominate future obligations. That money is usually both a medium of payment and a measure of obligations means that money is typically a medium of account. Indeed, that is the best test of whether something is money: if it is an exchange good used as a medium of account, it is unambiguously money.

If we replace medium of exchange with exchange good (and medium of payment), we can both apply normal supply and demand analysis and be clearer about money’s functions—including, as we shall see, what else can perform those functions. If we do not treat the notion of unit of account as some free-floating feature but connect it to its wider roles, we get a clearer role of money’s evolved functions. If we do not talk of store of value but instead analyse how money can either be an exchange good or an asset held for future use, we can consider in a more considered way—connected to normal supply and demand—how money functions.

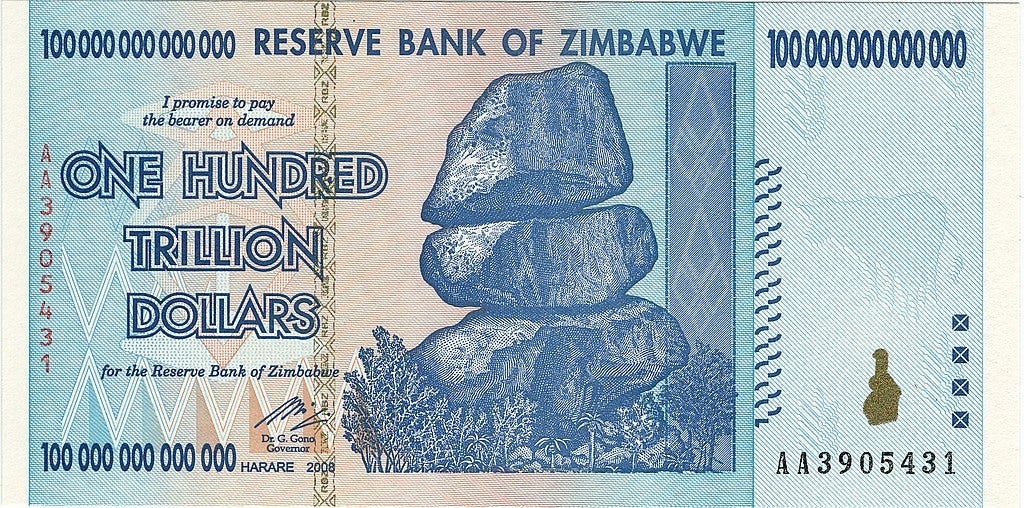

Hyperinflation is a useful corrective here. In conditions of hyperinflation, money is, by orders of magnitude, the worst store of value in the economy. Consequently, no one uses it as an asset. On the contrary, folk get rid of money via exchange as soon as possible. Yet, folk still use money because it still functions as the easiest way to transact with other people.

Inflation and deflation are monetary phenomena

That money is not neutral, at least in the short run—that money is a functioning part of the economy that is used for good (economic) reasons—does not mean that inflation and deflation are not monetary phenomena.

Inflation and deflation are monetary phenomena, being continuing shifts in the output-value of money. They occur for straightforward supply-and-demand reasons.

For instance, if money is an appreciating asset, more and more of it will be held as an asset, so less of it will be used as an exchange good, so its supply as an exchange good will shrink relative to output of other goods and services, so money’s output-value will rise. We call that deflation—falling money-prices for output.

The classic example of money as appreciating asset was when France went back on the gold standard in 1928. The franc was under-valued—gold bought more in France than it did elsewhere. So, gold flooded into France. The Bank of France effectively “sat” on the gold, pulling it out of the monetary system. That meant the gold remaining in the monetary system became scarcer, so more valuable in terms of goods and services. That meant that the money of every country on the gold standard began to appreciate in value. It became a more and more valuable asset. More and more of it was held as an asset, so less and less of it was spent, so spending (and so incomes) spiralled downwards while the burdens of debts rose (as folk had less and less income). This led to a wave of bankruptcies and financial collapses. This was the 1930s Great Depression, which countries only exited when they left the gold-standard system the Bank of France had turned into a deflation-debt downward disaster spiral.

If the supply of money used as an exchange good expands faster than output, its output value will fall. We call that inflation—rising money-prices for output, for goods and services.

A persistent fall in the output-value of money is inflation. A persistent rise in the output-value of money is deflation. Both are monetary phenomena—they are about the shifts in the interaction of the use of (supply of) money in exchange compared to the output offered (demanded) in exchange.

In a monetised economy, money is one side of (almost) all transactions. So, we can think of output of goods and services as aggregate supply and the use of money to buy goods and services as aggregate demand.

The existence of frictions in shifting resources between output of goods and services can matter, particularly over the longer-term. But, for short-term analysis, such frictions can usually be abstracted away from.

This is not a good analytical habit to get into, however, as it encourages assuming away a lot of social frictions. Standard models of economic growth—and approaches to foreign aid derived from them—generally underestimate the significance of transaction frictions. It also encourages the endemic tendency of mainstream economics to elevate efficiency to the extent of undermining social and institutional resilience. Both recent supply-chain issues and seriously underestimating the potential costs of migration have displayed these failings.

The reality that inflation and deflation are monetary phenomena does not require that money be neutral in its short-run effects on the wider economy. Indeed, both inflation and deflation come from money having economic functions generating supply-and-demand interactions that affect the wider pattern of transactions.4

Expectations matter

As, in a monetised economy, money is one side of (almost all) transactions, money gets used again and again. Economists call the rate at which money turns over in given time period its velocity. In physics, velocity = speed + direction of motion. Velocity is measured in distance per hour, while what economists mean by velocity of money is more like revolutions per minute.

The more you use money in transactions, the less you are holding it as an asset for future use. The more you are holding it as asset for future use, the less you are using it in transactions. So, the demand to hold money (k) is the reciprocal of its velocity (V). Hence k = 1/V.5 Time is continuous, but it is usually helpful to distinguish between immediate and longer-term decisions.

This spend/hold choice is where expectations matter most in inflationary and deflationary spirals. The more one expects money to lose output-value, the more incentive you have to spend it in the current time period and so to not hold it as an asset. The more one expects money to gain output-value, the less incentive you have to spend it in the current time period and so the more incentive to hold onto it as an asset.

The ability to print money in excess of output—i.e. impose an “inflation tax”—is attractive if ordinary taxation cannot keep up with what governments wish to spend. It also undermines feedbacks between government policies and effects on commercial activity. This has been a perennial problem in Latin America. It is possibly not a coincidence that the Great Enrichment of the C19th took off under various bullion standards—paper notes being backed by gold, silver or both (bimetallism)—that restrained the issuing of money, so elevated the significance to government revenue of commercial activity.

Both the first (Song dynasty) paper money and the second (Yuan dynasty) paper monies had periods of hyperinflation.

In the case of hyperinflation, as the output-value of money spirals downwards, people try to unload it quicker and quicker. So V heads towards infinity as both k and the output-value of money spiral towards zero.

This is why hyperinflation events are typically ended by replacing the hyper-inflating currency with a new currency—both because the hyperinflation expectations have to be broken and because the quantity of the old currency in circulation is so high.

If people believe a currency will stop being used without being swapped for a new currency, a hyperinflation spiral will be created as people unload the currency as quickly as possible before it stops being usable in transactions. This happened to the Confederate dollar at the end of the American Civil War.

For monetary policy, both the expected future output-value of a money and the expected future direction of total spending matter. If the monetary authority successfully anchors the expected value of money, but not the expected level of total spending (so, expected income), one can get major transaction crashes as folk stop spending as a precautionary measure because their income expectations have fallen. This is what happened in the Great Recession.

If, even worse, monetary authorities generate the expectation that the future output-value of money will rise, but do not anchor expectations about future spending, one can get a spiralling downwards deflationary collapse of spending, incomes and bankruptcies: a debt-deflation spiral. This what happened in the 1930s Great Depression.

If, however, the monetary authority manages to anchor both expectations about a stable output-value of money and expectations about future spending, then you can largely recession-proof your economy. You will still get a business cycle, just a much flatter one than there used to be. This is how Australia avoided the Great Recession and experienced the longest ever-recorded period without a technical recession.

If, however, there is a massive supply shock—for instance, imposing lockdowns that stop a lot of economic activity—even if there is lots of compensatory government spending, you will get a fall in transactions regardless. Once the lockdowns were over, folk will start spending their extra money—both because they can, and because they are working again. You will then get a surge in inflation, until the monetary authority takes the extra money out of the economy.

Credit is not money

Where thinking about money gets muddiest is in its interaction with credit. Credit is an obligation across time generated by borrowing.

A loan is an asset to the person lending and a liability to the person borrowing. But it is only an asset to the degree that the person borrowing does actually pay it back, along with the price charged for the use of someone else’s asset. Credit is therefore an asset that can simply evaporate.

Interest rates are the price of credit, the price of using someone’s asset denominated in money, including a risk premium against the possibility of the asset evaporating. Interest rates generate the base price of (financing) capital as other uses have to compete with the safest form of credit.

Credit is typically denominated in money, in the medium of account. Credit can also be a payment medium, as IOUs can be transferred. Thus transfer of funds via the banking system is payment by transfer of credit denominated in the medium of account.

We can thus see that a payment denominated in the medium of account need not be money. It can be a transfer of credit, of IOUs. That you pay from your bank account in something denominated in money makes it easy to think of that as money, but it is not, it is credit. How can we tell? Interest is paid on it.

The bank holds your money, [We talk of having “money in the bank”. We don’t. There is no set of notes and coins the bank is holding that is “yours”. (Unless such is in some safety-deposit box.)

What we have is credit with the bank, in the sense of Bank-OUs registered with the bank on which the bank pays interest. They are an asset for us and a liability for the bank. Those deposits of Bank-OUs can be used as payments. We transfer (as “money”) the Bank-Owes-Us to the person we are purchasing whatever from as a means of payment.

This is why I dislike defining money as a medium of exchange: credit is also a medium of exchange: or, even better, a means of payment. When folk say “money is credit” what they are identifying is that Bank-OUs are a medium of exchange denominated in a unit of account.]

The bank uses it, paying you for doing so, and promises to give it back to you on demand. Transfer between bank accounts is a transfer of [Bank-]OUs.

The terms outside money and inside money is where I find conventional language of monetary economics most unpersuasive. The conventional view is that some money is credit (and some is not) and some credit is money (and some is not). I agree that some credit is used as a means of payment, but prefer to keep credit and money more conceptually distinct.

So, I would agree that outside money is, generally, money. Inside money is, however, credit: it is credit generated within the banking system. Banks used to create money, when they issued banknotes, but that is no longer the case—apart from central banks and their local agents.

Thus, if one insists on that sharper delineation, then the so-called money multiplier is no such thing. It is simply the rate at which credit is generated within a banking system. It is the multiplication of obligations denominated in the medium of account that can be used as payment.

Money is not the only medium of payment. Credit can also be a medium of payment. Just because something is used as a medium of payment, and is denominated in the medium of account, does not mean it is money.

Money is an exchange good, something held to pay for other goods and services. Credit is a promise—one that can be used as payment—that is typically denominated in the medium of account.

The problem of bank runs occurs precisely because bank accounts are credit, are obligations to pay on which interest is charged for the use of someone else’s asset. If demands to pay overwhelm its capacity to pay, the bank collapses. There is a difference, however, from a bank being illiquid—not having the cash on hand to pay its obligations—and being fully insolvent—having liabilities in excess of its assets. The former is a temporary crunch that can be dealt with via outside support. The latter is a much more fundamental problem.

Coins and the branding premium

Historically, gold and silver often became the preferred form of money—the preferred exchange good(s)—as they are scarce, stable in supply and durable. This became even more true once coins were developed.

Coins generated output-value beyond their gold or silver content by being, in effect, branded bullion. They were standardised amounts of gold or silver. If folk could trust the branding, then the coins need not be checked for their bullion content. That increased their transaction utility, by increasing the information value of the branding, increasing their exchange value.6

The point of coining bullion was to generate that branding premium. This is, rather unhelpfully, called seignorage, but branding premium is a clarifying way to think about it.

Such coins could be predominantly be used within the jurisdiction of the coiner or they might be used substantially outside that jurisdiction. If they were predominantly used with the jurisdiction of the coiner—where the coiner had the authority to fix at least some output/obligation coin exchange rates—then there was an incentive to debase the currency. To attempt to use less bullion to pay off obligations or make other payments. Such debasement meant that the coins lost content stability, so the branding premium degraded.

This then creates the Gresham’s Law phenomenon: bad money driving out good [when there are some fixed rates of exchange]. That is, folk would economise on the use of bullion to make payments. So, the coins with the least bullion content would circulate while those with the most bullion content would be held onto—including their bullion being transferred to other uses.

As uncalculating cooperation turns out to be a costly and reliable signal of trustworthiness, people are likely to vary in their behaviour depending on who they are transacting with. This fits in with evidence that changing the framing of a transaction—particularly which conventions or other normative framings apply—can change people’s behaviour. Hence, who you are transacting with can also affect willingness to check coins.

This is also why cultural differences can really matter, as different cultures will apply different schemas (patterns of belief)7 and scripts (patterns of action) to the same set of interactions. Thus, when and if money is an appropriate gift varies markedly between cultures.

Incentives facing coiners can also vary. If coins were substantially used outside the jurisdiction of the coiner—so outside the capacity of the coiner to fix output/obligation exchange rates—then the branding premium became much more important to the coiner.

A particularly good example of this phenomenon was Imperial Spain. Imperial Spain operated as an an empire within a competitive European/Atlantic state system. Imperial Spain was an ongoing fiscal disaster—regularly running up debts it defaulted on. Imperial Spain was, however, a highly reliable coiner of silver, with its silver coins retaining stable silver content over long periods of time.

Imperial Spain used its coins externally to a very high degree. That is, it used coins extensively to transact with people it could not fix output/obligation coin exchange rates for. Hence it relied on generating a branding premium from branding reliability (i.e. silver-content stability). It proved able to be a reliable coiner of silver even when its silver mines and mints were an ocean away from its capital on another continent.

Imperial Spain then lost its Latin American holdings, which successfully revolted against imperial rule. The use of coins by the independent former colonies became dominated by their internal use, where output/obligation coin exchange rates could be fixed. Debasement of their coins set in.

Meanwhile, silver coins previously produced by Imperial Spain continued to circulate in China. Those coins came to increase in goods-and-services (output)-value, as demand for the branding reliability of the coins increased relative to their fixed supply.

Even though the silver content of Spanish coins were stable for long periods of time, they still lost goods-and-services (output)-value over time from the late C15th to the late C17th, as increases in production of silver—first from technological advancements in Central European mining, then from the silver mines of the Americas—steadily outpaced increases in the output they were exchanged for. This was the so-called Price Revolution: a monetary phenomenon.

Just-the-branding money

Money that is, in effect, just the branding premium—the branded medium has no other use—is fiat money. Fiat currency is branded tokens. Such money dominates the contemporary monetary universe.

There is an alleged paradox in fiat money. All fiat monies are finite: they will come to an end. At that point, the tokens constituting the money will have no exchange-value. Folk know this. Yet, fiat money continues to be used, it continues to have exchange-value.

The simple answer—a given fiat money may simply be then swapped for another money, as has happened many times—just puts the problem off, if one fiat money is swapped for another.

In reality, it is a false paradox. We have no idea how long any given fiat money will last, there being no information from the future and no life-span pattern for fiat monies—unlike, for example, living organisms, such as ourselves, that have specific life expectancies.

If we have no information that differentiates one time period from another on a particular matter, we have no reason to change our behaviour regarding that matter from one time period to another. Anything whose end-point is completely unknown is operationally eternal.

Until, of course, we do acquire information about the end point. At which point expectations about that end point really, really matter.

Economising on cognitive effort

Conscious calculation involves considerably more cognitive costs than unconscious calculation. Much of the point of training is to eliminate or minimise the need for conscious calculation.8 If reliable branding of money can dispense with the need for conscious calculation about each note or coin, that reduces the costs of transacting quite directly.

The use of money as means of payment and denominator of prices and obligations generates money illusion: calculative inertia based on economising on cognitive effort so that folk continue to use the branded denomination (“nominal value”) rather than its output-value (“real value”). To put it another way, the schema or framing applied to money simply uses its denominated (nominal) value. Money illusion is another manifestation of bounded rationality.

Economising on cognitive effort and information costs is basic to the appeal of money. That is where the branding premium comes from.

If folk are used to money having a stable value, they may not think to calculate changes in its output-value. They then rely on the branded denomination rather than its output-value.

If shifts in the output-value are small, the incentive to calculate such shifts—and to react accordingly—may be weak. The incentive, and the capacity, to adjust to changes in output-value varies.

Not all in-kind payments are barter

An annoying bit of sloppy thinking is when economists refer to manors as barter systems. They are no such thing. Manorial systems are structured around in-kind obligations, as were the temple and palace complexes of ancient Mesopotamia9 and Egypt.

Barter is a negotiated exchange not using a medium of account. Yes, it is an in-kind transaction, but not all in-kind transactions represent bartering.

Manorial systems use in-kind transfers based on what are typically customary obligations. There are some implicit or explicit bargains involved, but they are not continually re-negotiated in the way barter implies.

Thinking things through

My working presumption on matters monetary—including monetary history—is that, on such matters, Milton Friedman is presumptively correct. That is, it is fine to disagree with Milton Friedman, if you have good evidence assembled in a good argument.

That being said, his most famous bit of economic analysis—which included that social science rarity, successful prediction (that you could get both persistent inflation and high unemployment)—was a case of not thinking his thoughts all the way to the end. In his famous Presidential Address to the American Economic Association, Friedman critiqued the use of the Phillips Curve—that less unemployment meant more inflation, less inflation meant more unemployment—as a policy mechanism, trading off more of one for less of the other.

Friedman argued that purchasing a bit less unemployment via a bit more inflation (or vice versa) would collapse if folk learnt what you were doing and so shifted their behaviour. That is, leaning on the Phillips Curve statistical regularity for policy purposes would eventually mean the statistical regularity would disappear as folk changed their behaviour. (The evidence is clearly that the Phillips Curve comes and goes.)

Friedman’s policy solution was a stable rate of monetary growth. The problem with that is that this policy also relied on a statistical regularity—stable rates of holding money as an asset. The response to adopting such a monetary rule was for folk to change their behaviour, so that the demand to hold money was no longer stable—the statistical regularity went away when lent on for policy purposes.

This led to the formulation of Goodhart’s Law:

Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.

Market monetarism represents a response to this. It is the view that money policy is fundamentally about managing expectations—which folk generate from available information, including the policy stance of the central bank—without attempting to rely on (unreliable) statistical regularities.

So, my working presumption on matters monetary—including monetary history and monetary policy—is that Scott Sumner is presumptively correct. In the above, I depart from the ways mainstream economics talks about money, but I still regard my fundamental outlook as a market monetarist one. Fortunately, Scott Sumner has also joined Substack.

References

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

David Chilosi & Oliver Volckart, ‘Good or Bad Money? Debasement, Society and the State in the Late Middle Ages,’ LSE Economic History Working Papers No. 140/10 May 2010, eprints.lse.ac.uk/27946/.

Irving Fisher, The Money Illusion, Start Publishing LLC, [1928] 2012.

Milton Friedman, ‘Role of Monetary Policy,’ American Economic Review (March 1968), Vol. 58, No. 1, 1-17, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/1161/item/2352.

Milton Friedman, Money Mischief: Episodes In Monetary History, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1992, 1994.

Dror Goldberg, ‘Money with partially directed search,’ Journal of Monetary Economics, 54, 2007, 979–993, www.drorgoldberg.com/monetary_theory

David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years, MelvilleHouse, 2011.

Robert L. Greenfield & Leland B. Yeager, ‘Money and Credit Confused: An Appraisal of Economic Doctrine and Federal Reserve Procedure,’ Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Oct. 1986), Pp. 364-373, www.jstor.org/stable/1059419.

Philip Grierson, ‘The Origins of Money,’ Research in Economic Anthropology, Vol. 1 1978, 1-35, docs.google.com/file/d/0BwXoQMQ7Va5_ODI0MGZkMTEtMTdlNS00YmY4LTgyNTctZjI1NDBmMTFmMDAx/edit?hl=en.

Hanhui Guan, Nuno Palma, Meng Wu, ‘The Rise and Fall of Paper Money in Yuan China, 1260-1368,’ September 2022, Updated January 2024, Economics Discussion Paper Series EDP-2207, School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Robert E. Hall and Thomas J. Sargent, ‘Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of Milton Friedman’s Presidential Address,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 32, Number 1, Winter 2018, 121–134, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.32.1.121.

Cameron Harwick, ‘Money and its institutional substitutes: the role of exchange institutions in human cooperation,’ Journal of Institutional Economics (2018), 14: 4, 689–714. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2707833.

David Hume, ‘Of Money,’ Essays Moral, Political and Literary, Liberty Fund, [1752] 1987.

Uri Gneezy, and Aldo Rustichini, ‘A Fine is a Price,’ Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1, January 2000. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=180117

J.J. Jordan, M. Hoffman, N.A. Nowak, D.G. Rand, ‘Uncalculating cooperation is used to signal trustworthiness,’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2016, Jul 20; 113(31): 8658-63. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1601280113#

Nobuhiro Kiyotaki & John Moore, ‘Evil is the Root of All Money,’ Clarendon Lecture, Lecture 1, 26 November 2001, www.princeton.edu/~kiyotaki/papers/Evilistherootofallmoney.pdf.

Arnold Kling, Specialization and Trade: A Re-Introduction To Economics, Cato Institute, 2016.

Thomas McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, Allworth Press, 2002.

Christopher M. Meissner, ‘A New World Order: Explaining The Emergence Of The Classical Gold Standard,’ NBER Working Paper 9233, October 2002. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9233.

Robert Mundell, ‘The Uses and Abuses of Gresham’s Law,’ August 1998, paper prepared for Zagreb Journal of Economics, Volume 2, No. 2, 1998, www.columbia.edu/~ram15/grash.html.

John Munro, ‘The Monetary Origins of the ‘Price Revolution’ : South German Silver Mining, Merchant-Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470-1540,’ Department of Economics and Institute for Policy Analysis University of Toronto, Working Paper No 8, June 1999, revised 21 March 2003, www.economics.utoronto.ca/public/workingPapers/UT-ECIPA-MUNRO-99-02.pdf.

Daniel H. Neilson, Minsky, Polity Press, 2019.

Peter St. Onge, ‘How Paper Money Led to the Mongol Conquest: Money and the Collapse of Song China,’ The Independent Review, v. 22, n. 2, Fall 2017, 223-243.

Joseph M. Ostroy, ‘The Informational Efficiency of Monetary Exchange,’ The American Economic Review, Vol. 63, No. 4 (Sep., 1973), 597-610, www.jstor.org/stable/1808851.

Marvin A. Powell, ‘Money in Mesopotamia,’ Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 39, No. 3, (1996),224-242, www.jstor.org/stable/3632646.

A. Hingston Quiggin, A Survey of Primitive Money: The Beginnings of Currency, Methuen, 1949.

R. A. Radford, ‘The Economic Organization of a P.O.W. Camp,’ Economica November 1945, www.clsbe.lisboa.ucp.pt/docentes/url/jcn/ie2/0POWCamp.pdf.

Walter Scheidel, The Monetary Systems of the Han and Roman Empires, Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics, Paper No. 110505, February 2008, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1096440.

George Selgin, Good Money: Birmingham Button Makers, the Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage 1775-1821, The Independent Institute, [2008] 2011.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Wealth of Nations, Vol.I, Chapter xi, Liberty Classics, [1776] 1981.

Scott Sumner, The Midas Paradox: Financial Markets, Government Policy Shocks, and the Great Depression, Independent Institute, 2015.

Scott Sumner, The Money Illusion: Market Monetarism, the Great Recession, and the Future of Money, University of Chicago Press, 2021.

James Tobin, ‘Commercial Banks as Creators of ‘Money’’, Banking and Monetary Studies, (ed. Dean Carson) 1963, 408-419, cowles.econ.yale.edu/P/cm/m21/m21-01.pdf.

Filip Vesey, ‘Optimal Payment Arrangements: Money vs. Reciprocal Exchange,’ pantherfile.uwm.edu/vesely/www/optimal_payment.pdf.

Harvey Whitehouse, Pieter François, Patrick E. Savage, Daniel Hoyer, Kevin C. Feeney, Enrico Cioni, Rosalind Purcell, Jennifer Larson, John Baines, Barend ter Haar, Alan Covey & Peter Turchin, ‘Testing the Big Gods hypothesis with global historical data: a review and “retake”,’ Religion, Brain & Behavior, (2022).

I dislike the way Austrian School economists such as Carl Menger von Wolfensgrün (1840-1921), Eugen Ritter von Böhm-Bawerk (1851-1914) and Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) talk about the origins of money as being a result of rational optimising by private agents that “naturally” tends toward gold. Money is an emergent historical phenomena that has taken many forms, with silver historically having been a much more important monetary metal than gold. Moreover, as the state is the largest economic actor in any state society—something that, for instance ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) was well aware of—state action is deeply intertwined with the history of money. For a much more anthropologically-grounded analysis of the origins of money and exchange institutions see Harwick (2018).

What economists call the price level (P).

Humans operate across time, both individually and as lineages. An asset is anything of economic value that folk use across time. It may be used for production of goods and services but it may be simply a store of value. Mainstream economics tends to focus a little too much on production of goods and services, and on efficiency, thus under-estimating the importance of resilience—the ability to persist across time—and being somewhat awkward in analysing assets that have value across time but are not used to produce other goods and services.

Historians have an unfortunate tendency to connect inflation with population growth. Sir Niall Ferguson does it here, David Hackett Fischer does it in The Great Wave, various historians do it regarding the Price Revolution. It is nonsense. In 1820, the UK had a population of 21m; in 1913, its population was almost 46m, so had more than doubled. Over that period, its GDP had increased sixfold. Yet, its price level in 1913 was effectively the same as in 1821, when it had gone back on the gold standard. The use of money in exchange had kept pace with the increase in population and output.

There were periods of (mild) inflation from increases in gold production in the 1850s and 1860s—due to the Californian and Australian gold-rushes—and from the late 1890s—due to the Klondike and Kalgoorlie gold-rushes and the South African gold mines. There was a prolonged bout of deflation from 1873 to the mid-1890s as France, Germany, and the US all went onto the gold standard, raising the monetary demand for (and so value of) gold and so the output-value of gold-backed money—gold being the medium of account in a gold standard. An effect aggravated by other countries entering the gold standard (e.g. Austria-Hungary in 1892). The net effect on the UK price level across the entire period was effectively zero: the changes balanced out.

Hence the equation of exchange: Money (M) times rate of use (V) = Price level (P) times output (y). MV = Py. Since the demand to hold money (k) is the reciprocal of its rate of use (V), the equation can also be rendered as M = kPy. If the demand to hold money (k) is stable, changes in the growth of M relative to output (y) will drive the price level (P).

In his deeply historically flawed book Debt: The First 5000 Years, anthropologist David Graeber connects the inventing of coins to the rise of Philosophy. The frequently repeated claim that the Axial Age sees the birth of moralising “Big God” religions is not supported by the historical evidence. That the era sees the simultaneous shift to more systematic and more abstract thinking about the world across various Eurasian civilisations is clearly true. Systematic and abstract thinking that was then applied to religion.

Coins represented a thing that was a physical object, yet had this extra, non-physical property; generated an increase in interactions without personal connections; and did so in the context of conflict between variously organised states. That such circumstances generated the rise of Philosophy in the Greek, Indian and Chinese civilisations is not surprising. Especially given that the Scythian steppe culture a provided potential avenue of contact between these civilisations.

Schemas can also be thought of as (cognitive) framings.

What might be called the Zen and the Art of Archery effect. That so much of our cognition is not conscious is how many of our evolved adaptations operate. This is also where the worship of human autonomy goes wrong. We tend to vastly overestimate how much of our thinking is conscious (as I discuss in my Why Ritual essay). We are technological beings because we are social learning beings and hence cultural beings. A whole lot of stuff gets selected for across social evolution because it works (Chesterton’s Fence at scale). The worship of human autonomy easily ends up shedding stuff that we need in favour of what feels good in the moment. Hence, as Malcolm Collins points out here, those in modern Western societies who most reject embedded these-things-work inheritances end up being the most anxious, unhappy, depressed, etc.

Like medieval manorial Europe, the societies of the ancient Mesopotamian palace and temple complexes also had vigorous commercial activity. Karl Polanyi and Sir Moses Finley’s depictions of ancient Mesopotamian and Roman economies respectively as lacking such commerce is quite false.

Is your summary of the situation with France hoarding gold and exacerbating (or even launching?) the Great Depression another recommendation to go with "flexible" fiat monies instead of "rigid" commodity varieties?

" If, however, the monetary authority manages to anchor both expectations about a stable output-value of money and expectations about future spending, then you can largely recession-proof your economy. You will still get a business cycle, just a much flatter one than there used to be. This is how Australia avoided the Great Recession and experienced the longest ever-recorded period without a technical recession." Yeah, OZ!! Why can't the rest of us learn from your successes??

"If we do not talk of store of value but instead analyse how money can either be an exchange good or an asset held for future use, we can consider in a more considered way—connected to normal supply and demand—how money functions." Perhaps this is some "theory vs. practice" territory. I have long felt that the MMTers and others don't give the store of value function the attention and merit it deserves. Your viewing it as an asset with supply and demand implications is helpful and interesting, but even held as an asset, it is essentially an abstract surrogate place holder for the value previously created or obtained (with that attendant fragility, etc.). Postponing consumption for saving and investing is usually considered a good personal finance practice, even if the economists might like to see velocity increase. Naturally, today we need to recognize that the current $ values of our investment portfolios include both a real wealth added element and a phony inflation added quantity.

"Inflation and deflation are monetary phenomena, being continuing shifts in the output-value of money. They occur for straightforward supply-and-demand reasons." I fully agree with this, but the "adjustments or distortions" you describe reflect the difficulties of trying to manage an economy where the participants (in the US anyway) make 10 to 30 billion purchasing decisions every day.