Understanding the Great Enrichment: how mass prosperity replaced mass poverty

Britain became the first country to do learning-by-experiment at scale.

This post is an interlude, looking at the key breakthrough to mass prosperity, before completing the series on property with the post on how China took off. If you are interested in the history of the Industrial Revolution, I strongly recommend Anton Howes’s Substack, The Age of Invention.

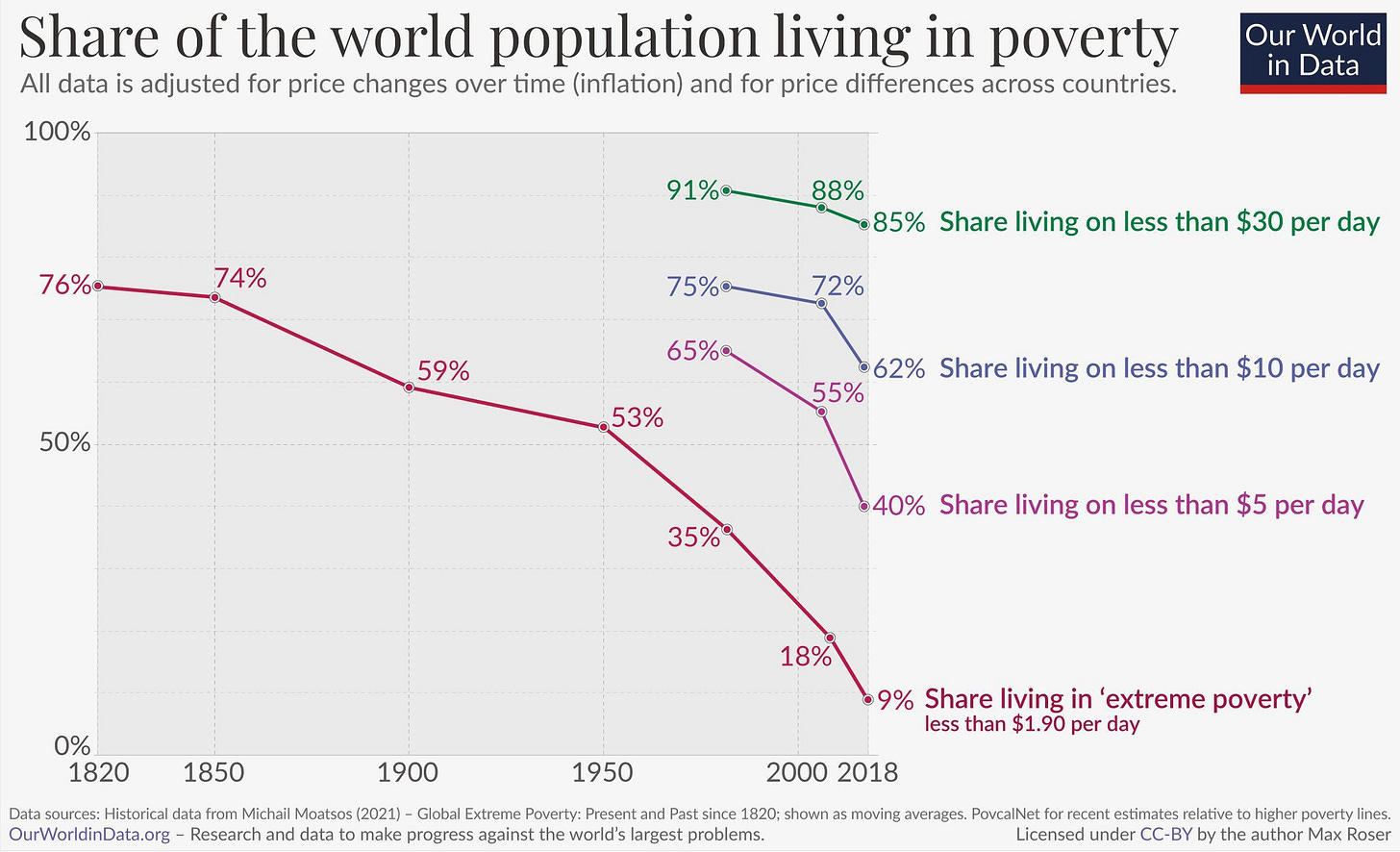

When we talk about the exit from mass poverty—as occurred in China after 1978—we are talking about achieving modern economic growth. This starts with what is often called The Industrial Revolution, but it is better thought of as The Great Enrichment: the rolling replacement of mass poverty with mass prosperity through compounding economic growth. It kicks off as a mass economic phenomenon with the application of steam power to transport (so to trade) via the development of steamships and railways in the 1820s.

The trouble with understanding the causes of the Industrial Revolution aka Great Enrichment is that it starts in precisely one country—Great Britain. A singular historical phenomenon is very hard to analyse successfully, as you cannot readily test different explanations.

This is also a separate question from why Europe developed a set of unusually effective (and adventurously imperial) states. It is easy to conflate the two together but they are quite separate.

By the 1820s, European states already dominated the globe for reasons that are entirely independent of the Industrial Revolution and which reach back into Europe’s medieval history. The great Homo sapien super power is non-kin cooperation, and the evolution of European Christendom had put non-kin cooperation on steroids.

As early as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), great European wars were already world wars. Historian Thomas Babington Macaulay famously wrote of Frederick the Great of Prussia about the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748)

In order that he might rob a neighbor whom he had promised to defend, black men fought on the coast of Coromandel and red men scalped each other by the great lakes of North America.

A quote which leaves out the extensive military operations in India.

When looking at the various explanations that have been offered for the Industrial Revolution, it is hard to see what is culturally and institutionally distinctive about C18th Great Britain compared to other European states—including England itself prior to the 1707 Act of Union with Scotland. Yes, the Glorious Revolution led to significant institutional changes—but they were based on adapting Dutch practices under a Dutch King. England-cum-Britain became institutionally more like the Dutch Republic, not less.

Parliamentarianism, family structures, the Scientific Revolution, central banking, relatively high wages, productive agriculture, being a highly mercantile society: none of these things were distinctive to C18th Britain compared to other European states while many applied to England well before the C18th. Just because both X and Y happened in Britain, it does not mean that X caused Y. This especially so if X also happened in countries where Y did not.

Moreover, there have been various economic “effervescences” across human history. None of them achieved modern economic take-off because none of them achieved technological take-off—specifically, access to new forms of energy at scale. Wind and water power were useful, but not transformative.

Without such technological take-off, Malthusian pressures were sufficient in themselves brought such outbreaks of economic growth to an end. Expanding population coming up against resource constraints would eventually “eat up” the economic growth. This regularly extended to some level of political collapse, due to shrinking social niches creating some combination of popular revolt and internecine elite struggle.

A key difference with modern economic growth is precisely the breaking through of Malthusian constraints—both through technological change expanding resources faster than population and falling human fertility.

The key modern economic take-off was the Energy Take-off: the adapting—starting with steam engines—of new forms of energy to economic activity at scale. The serious take-off was not from steam power in mines and factories—which affected specific goods and services—it was applying steam to transport, via steamships and railways, so touching all economic activity.

Why did that technological breakthrough happen in Britain and nowhere else? Because Britain was the first society to move systematically from learning-by-experience to learning-by-experiment at scale. Even more specifically, it commercially motivated and exploited that learning.

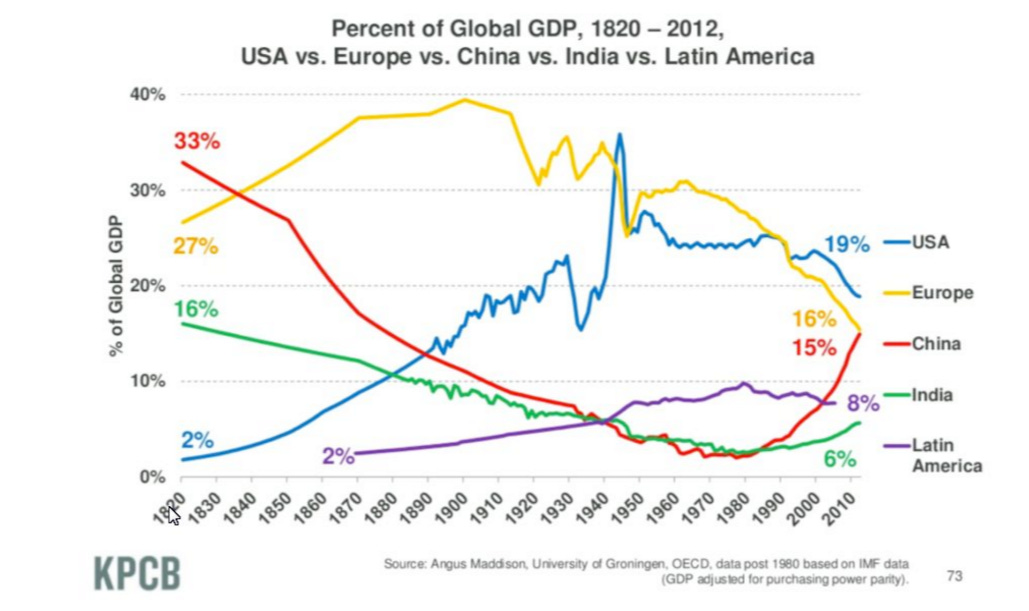

China dominated invention from c.450BC to c.1450AD because it was the most populous civilisation—apart from India—and it was far more meritocratic and culturally unified than India. China therefore dominated learning-by-experience, so invention.

By the mid C15th, Europe had already become better at innovating from learning-by-experience than China. The intense competition between European states clearly had much to do with this, but so did Europe’s unusually empowered merchant elites. By the high medieval period, Europe had already become a place where application of technology to commercial problems had become increasingly prevalent.

Starting around 1500, Europe took the printing press (and paper), the compass and gunpowder—all originally Chinese inventions—and transformed the world with them in a way China did not. Apart from the printing press, these were all tech-transfers from China. The same technology operated dramatically differently in different institutional environments.

None of this operated distinctively in Britain until the C18th, when there was an explosion in jobbing artisans using learning-by-experiment to solve commercial problems via organisational and technological innovation. Why did this happen then, in that place? Because of Sir Isaac Newton and his example and achievement being extolled by the Anglican Church.

Newtonian mechanics were an incredible intellectual and scientific achievement. The visible world could be explained—and predicted—by mathematically expressed scientific principles.

Most European Churches were not thrilled by Newton’s achievement. They preferred a vision of a personal, active in the universe, God. A God you needed to talk to your priest or pastor to know how to keep on the right side of. Newton’s Clockwork Universe was not helpful to this.

The Anglican Church took a very different view. Anglican vicars regularly sermonised on the genius of a God who could create the complexities we saw around us through such elegant principles. Schools took up this idea. Alexander Pope’s famous epitaph expressed this sentiment:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

Newtonian mechanics were not merely elegant principles mapping the structure of the observable world. They were principles found by, and the useful application thereof could be discovered by, experiment.

So people did. Jobbing artisans experimented to find technological solutions to commercial problems, which you could then make money from. This generated a society that—for the first time in human history—was applying learning-by-experiment at scale. This has become known in the literature as broad adoption of engine science, but it is better understood more broadly as learning-by-experiment.

That created the technological take-off, the energy take-off, that we call the Industrial Revolution. Unlike other explanations for the Industrial Revolution, this has a direct connection to the discovery process that led to the energy take-off. As economic historian Jack Goldstone notes:

by 1850 the average English person has at his or her disposal more than ten times the amount of moveable, deployable fuel energy per person used by the rest of the world’s population.

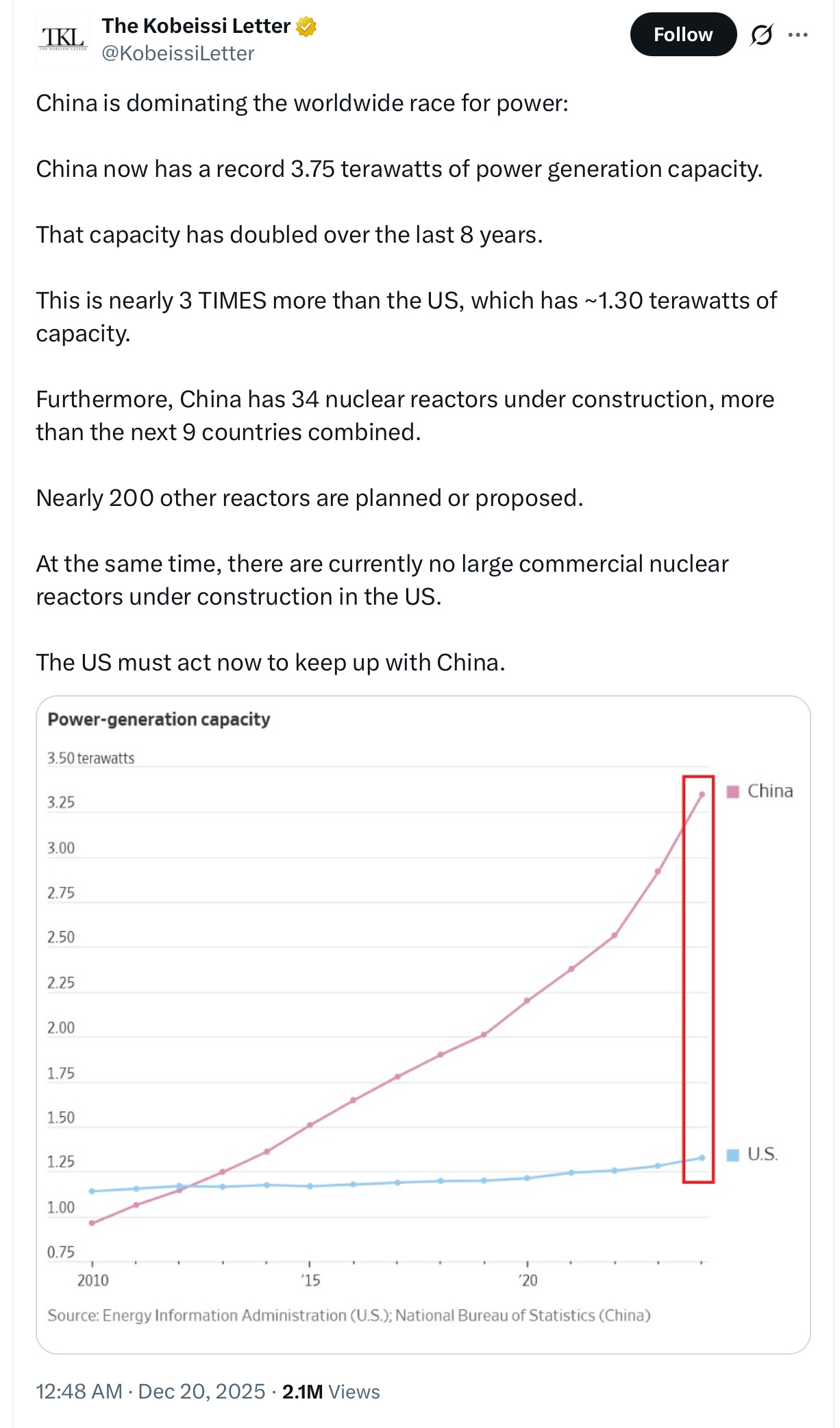

The availability of cheap energy is the single most important thing in economic take-off and mass prosperity. (It is much more important than, for example, free trade.) It is also the indicator that most suggests that the US will lose out to China.

Central to the current economic travails of the UK and Germany is ludicrously expensive energy. Which brings us to the other crucial aspect of Britain’s economic take-off.

No interest group proved powerful enough and motivated enough to block it.

If you want to identify a key feature of Britain’s institutional arrangements, that was it. No one vetoed the take-off.

On the contrary, the British elite increasingly went out of its way to facilitate it. Britain moved from notoriously corrupt politics c.1740 to notoriously honest government c.1880 because the UK Parliament systematically abolished official discretions—by doing what we now, rather clumsily, call “de-regulation”. The British state abolished licensing, monopolies and other regulatory barriers. It thereby systematically reduced the transaction friction that it imposed on economic actors. It also thereby systematically gutted the market for official discretions, so corruption.

The consequence was that the British economy became productive at a scale unprecedented in human history. That gave the British state flows of revenue at rates unprecedented in human history. At the time of the first Opium War (1839-1842), the British state had four times the revenue of the Qing Empire’s central government, despite the Qing Emperor presiding over approaching a third of both humanity and world GDP.

If you want to judge how important it was to have no one able to veto the take-off, I direct you to how the EU—whose Eurocrats have precisely two powers: the power of No and to subsidise—has presided over a striking failure by Europe to match the technological dynamism of the US and China, or sustain the same level of economic activity as the US.

People can find the processes of exploration, experimentation and discovery confronting, especially if it challenges their sense of already knowing. The resistance to even the concept of prediction markets seems to have an element of this.

There is a far more dramatic historical example of vetoing advancement than the EU. Within fifty years of the invention of the printing press around 1440, printing presses had spread all over Latin Christendom. The appeal of having books printed at two per cent of the cost of a hand-written book was obvious.

The first North African printing press for Muslims was established in the 1830s in Cairo. It took almost four centuries for the printing press to move from the Christian north of the Mediterranean to the Muslim south.

Think what Europe did with the printing press across those centuries. Think what Islam did not do.

If you want to understand how the civilisation right next to Europe could fall so far behind it, that’s how. The religious scholars, the ulama, were able to veto the key technology of the printing press for Muslims. Their entire civilisation fell catastrophically behind as a result.

A China that adopts—as it has—learning-by-experiment, has access to cheap energy and has reliable mechanisms to turn discovery into applied technology, can be expected to go back to dominating human invention, as it did from c.450BC to c.1450AD. If India, now even more populous, can overcome its long-term drags on doing so, it may eventually move into first place.

That is the other question to ask—which civilisation currently has the more toxic veto-coalitions: the US, the rest of the West, or China? But that leads us to the next post.

References

Books

Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Crown Business, 2012.

Douglas Allen, The Institutional Revolution: Measurement and the Economic Emergence of the Modern World, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Yoram Barzel, Economic Analysis of Property Rights, Cambridge University Press, [1989] 1997.

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, [1983] 2005.

Jean Gimpel, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages, Pimlico, [1976] 1992.

Eric L. Jones, The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia, Cambridge University Press, [1981] 2003.

Eric L. Jones, Growth Recurring: Economic Change in World History, University of Michigan Press, [1988] 2000.

Eric L. Jones, Cultures Merging: A Historical and Economic Critique of Culture, Princeton University Press, 2006.

Timur Kuran, The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830: Volume I, Integration on the Mainland, Cambridge University Press, [2003] 2010.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830: Volume 2, Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands, Cambridge University Press, [2009] 2013.

Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path, (trans.) Gerard Chapple, University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2010.

Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy (Graz Schumpeter Lectures), Princeton University Press, 2016.

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Harvard University Press, [1965] 1982.

Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation and Social Rigidities, Yale University Press, 1982.

Mancur Olson, Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships, Basic Books, 2000.

Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, Princeton University Press, 2000.

John P. Powelson, Centuries of Economic Endeavor: Parallel Paths in Japan and Europe and Their Contrast with the Third World, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Jared Rubin, Rulers, Religion & Riches: Why the West Got Rich and the Middle East Did Not, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Articles, essays, etc.

Stephen Broadberry, ‘Accounting for the Great Divergence: Recent findings from historical national accounting.’ Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers, Number 187, March 2021. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/accounting-great-divergence-recent-findings-historical-national-accounting

Jack A. Goldstone, ‘Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the “Rise of the West” and the Industrial Revolution,’ Journal of World History, (2002) Vol. 13, No. 2, 323-389. https://culturahistorica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/goldstone-efflorescences.pdf

Meir Kohn, ‘Money, Trade, and Payments in Preindustrial Europe,’ in S. Battilossi et al. (eds.), Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, Spring, 2018. https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-981-10-0622-7_15-1

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021). https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/alternative-theoretical-framework-economics

Paul Lunde, John M. Munro, Caroline Stone, ‘Arabic and the Art of Printing,’ Aramco World [now Saudi Aramco World], issue March/April 1981, 20-35, http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198102/arabic.and.the.art.of.printing-a.special.section.htm

Debin Ma, ‘Rock, scissors, paper: the problem of incentives and information in traditional Chinese state and the origin of Great Divergence,’ Economic History Working Papers 37569, London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History, 2011. https://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/WorkingPapers/Economic-History/2011/WP152.pdf

Joel Mokyr and John V.C. Nye, ‘Distributional Coalitions, the Industrial Revolution, and the Origins of Economic Growth in Britain,’ Southern Economic Journal, (2007), 74: 50-70. https://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/jmokyr/Charleston-Olson-8.PDF

Mieke Molthiff, ‘The Industrial Revolution and a Newtonian Culture,’ Aug 24 2011. https://www.e-ir.info/2011/08/24/the-industrial-revolution-and-a-newtonian-culture/

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Coevolving institutions and the paradox of informal constraints,’ Journal of Institutional Economics, 2021, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/CE95D185B7EA557C5D0066FA7D785BCB/S1744137420000600a.pdf/div-class-title-coevolving-institutions-and-the-paradox-of-informal-constraints-div.pdf

Jan Luiten van Zanden, Eltjo Buringh, and Maarten Bosker, ‘The rise and decline of European parliaments, 1188–1789,’ The Economic History Review, 2012, 65, 3, 835–861. https://www.academia.edu/20611214/The_rise_and_decline_of_European_parliaments_1188_17891

The little appreciated driver of the changes you catalog is England’s unique system of primogeniture. I know, it sounds odd, but by requiring all of an estate to go to the eldest son, it cut loose a bunch of other children who were a) educated, b) used to luxury, c) politically connected, and d) HIGHLY motivated to improve their (newly impoverished) position in life. Couple that animal fervor with cheap energy and you get 1850 Great Britain.

In our times the redistribution of Inflation by pumping the markets with free money has been conflated with prosperity, sort of confounding interest and contracting wealth. Fortunately we’ve begun to come to our senses and are reshoring industries to America.

May all do the same.

Amen