The limits of social science (I)

Networks of people migrate, not robotic workers nor interchangeable economic “particles”.

I recently discovered on a bookshelf a book that I had forgotten I owned and forgot that I had read. (I read a lot, and own a lot of books, it happens.) The book was We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative by noted migration economist George Borjas.

I have since re-read the book. I commend We Wanted Workers to anyone interested in the economics of migration. Re-reading it reminded me just how intellectually disgraceful the open-borders economic advocacy is.

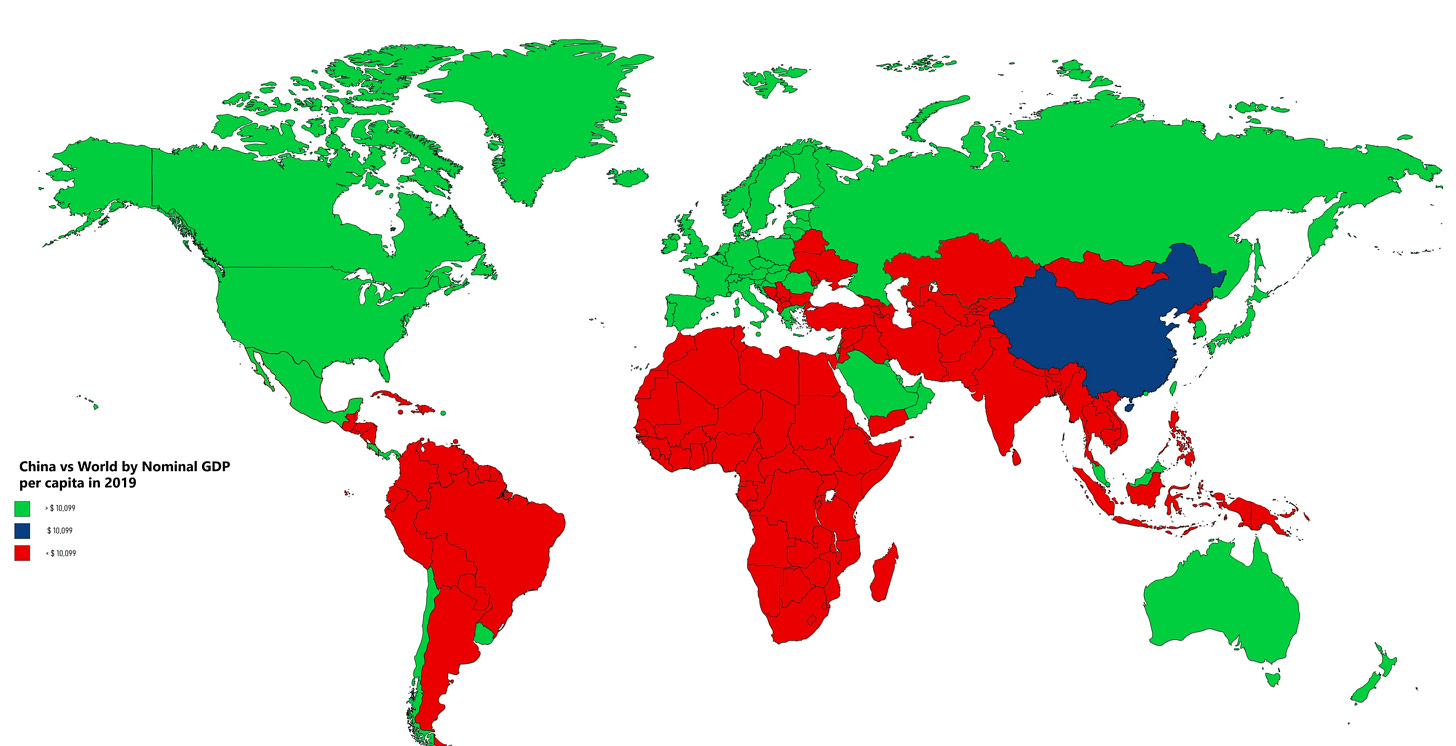

The context that led to the surge in open-borders economics was that free trade was supposed to lead to an equalisation of wages between countries based on significant increases in income (Pp32-3). This was the prediction of Theory. It didn’t happen. Rather than getting into the weeds and work out why it didn’t happen, the open border economists doubled-down on their Theory and decided what was required was even more cross-border flows—of people, not just goods and services (Pp 33-5).

It is hard to over-state how intellectually disgraceful this was. They had a hypothesis—free trade would equalise wages across countries. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) provided a test of the hypothesis. The hypothesis was proven untrue. Rather than working out why they were wrong, they just doubled down on the Theory that had generated the disproven hypothesis.

This is a classic instance of why so much (Social) Theory pushed by academics is crap. The Theory was used to select and assess the evidence, rather than evidence being a test of Theory. When the evidence was unhelpful, they doubled down on their Theory. Just as the grotesque failures of Marxism has generated endless versions of “real Communism hasn’t been tried” here was “real (market) liberalisation hasn’t been tried”.

This double-down on Social Theory pattern goes back to Marx, whose entire system was about using Smithian, Ricardian and Malthusian political economy to support his previously reached socio-metaphysical conclusions; conclusions that then directed his use of such political economy. Marx aped being a social scientist, but his methodology was profoundly anti-scientific. It continues to be the dominant methodology of all the traditions that descend from him, including the various versions and offshoots of Critical Theory.

The reductio of this is Critical Constructivism—which has been taught to trainee teachers for decades across North America and much of the Anglosphere. It claims that the rightness of a theory or claim can be assessed by its (alleged) implications for approved (and unapproved) groups because reality is socially constructed and all such constructions—including science—are expressions of power. Hence, that sex is biological and binary—there being only two types of gametes—is trumped by the implications for the claims of Trans folk, as all “righteous” folk understand.1

This is also why arguing with a Libertarian can be so much like arguing with a Marxist. They use their Theory to select and assess the evidence. If they get into trouble, they refer back to their Theory. They do this as their Theory is central to their identity: making your Theory or model central to your identity is always a mistake if one wants to genuinely understand reality.

The limits of social science

Both Libertarians and Marxists want their Theory to do what social science cannot do. Social science can identify mechanisms—for example, gains from trade, opportunity cost, comparative advantage—and patterns—such as that relations precede transactions or the significance of breaking up local connections (aka social capital).

What social science cannot do is generate an accurate unified Social Theory, as people are not interchangeable economic/social particles, so you can’t generate a Social Physics. In the words of a review article on the effects of culture (Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869):

Although using very different methodologies, the studies all provide evidence leading to the same general conclusion: individuals from different cultural backgrounds make systematically different choices even when faced with the same decision in the same environment. (Emphasis added.)

Investor Charlie Munger made the same point about the impossibility of a Social Physics when he observed:

A great philosopher said 'A man never steps into the same river twice, the man is different and so is the river when he goes in the second time.' That's the trouble with economics. It's not like physics. The same damn recipe done a different time gets a different result.

Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t: change the culture of the people, and different results become far more likely. Adam Smith’s critique of the Man of System continues to be correct:

The man of system, on the contrary, is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess–board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess–board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess–board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it.

Much the same point applies to grand philosophical Theories, as they attempt to Theorise human nature and social dynamics with the same (mistaken) generality. As the editor of First Things, R.R.Reno observes of philosopher Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994), the author of The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945):

1:03:37 I think he [Popper] was a liberal. He tried to theorize liberalism in this grand way and I think that that's always a mistake. Liberalism is a habit of mind, it's a tradition, it's a social tradition. I think when it's overly theorized, it becomes kind of a flesh-eating-dogma liberalism. … it's ever changing [liberalism] … because the protection of human dignity and genuine freedom is always changing because the circumstances of life are always changing. I mean to be a liberal parent means something different when your child is 6, 16 and 60 and 36. [It also means something different in America and Britain] and rightly so. … (Emphasis added.)

Being a Person of System has at least two great appeals. First, it potentially provides the basis for wielding a great deal of power over one’s fellow humans. Second, it elevates one’s moral and cognitive status: one can dismiss those who reject your System, your Theory, as ignorant, possibly stupid, even corrupt or otherwise immoral. It also readily feeds into that deeply corrosive claim “you have to believe X to be a good person” so that the social inclusion/exclusion effects trumps how accurate or inaccurate claims are.

All this is separate from the replication crisis, which is about poor methodology and bad incentives—“publish or perish” and the grants treadmill. The limitations on what social science can do—and can be—are much more fundamental. They come from social science being the study of human agents who are so variant along so many dimensions.

This is without the problem of said agents reacting to what social scientists do when they study people, and to what they say about people, plus the various human blindnesses of social scientists, as well as the feedback effects of such blindnesses on the conduct of social science. The refusal of so much of what passes itself as social science to ensure its analysis is consilient with evolutionary biology, and evolutionary anthropology—when everything social is emergent from the biological—is, in itself, scientifically disabling.

What the replication crisis does tell us is that the claims academics make—particularly about how the world should be ordered—should be subject to massive discounting, precisely because the accountability and reality-tests are so patently inadequate. The attempt to bureaucratise—and so routinise—scientific and other discovery by peer review, citation metrics and government grants has proved to be greatly inferior to a robust culture of scientific inquiry and scholarly endeavour with a sense of custodianship. A sense of custodianship that both modern academic culture and modern managerialism not merely lack, but systematically undermine.

One can make a powerful argument that the pretensions of social science—or what has paraded itself as social science—collectively constitute the most disastrous human endeavour of the last two centuries. From promoting bad policy during the Irish Great Famine (1845-52), to the catastrophes of Revolutionary Marxism, and the disastrously stupid ideas Western academics planted in their non-Western students—African socialism or the Licence Raj anyone? —the downside record has been a ghastly one.

The massive global surge out of poverty in recent decades was far more driven by the power of examples—notably of Japan and the Asian Tigers—than Theory. It was mostly a matter of letting commerce do its thing by rolling back policies originally justified by destructively wrong “social science”, much of which was age-old intellectual prejudice against commerce repackaged to fuel various status-games and power-grabs.

To the extent that Critical Theory and its offshoots (aka “wokery”)—all based on patently false “blank slate” notions of humanity—represent a new pattern, it is a shift to the damage being worst inside the Anglosphere rather than elsewhere. This has much to do with why academe is increasingly losing its social license.

Culture matters

A habit of mind, a social tradition, is not a generic feature of the human condition. That is dramatically true of the liberal habits of mind. So many of the failures of Western foreign, social and migration policy—particularly since 1991—have rested on general Theories of the human condition that are simply not true.

There is also the problem of missing mechanisms: mechanisms that we have not nailed down yet. As I have pointed out before, you cannot predict the full effects of migration without a robust theory of long-term economic growth, which mainstream Economics simply does not have. You instead have to carefully identify what social mechanisms and patterns are in play—all of them, not merely those convenient to your Theory. A great deal more analytical and intellectual humility is in order—particularly, a great deal more respect for the complexities revealed in history—than many economists (with their Samuelsonian delusions of operating a Social Physics) have been willing to display.

American history is often cited as demonstrating the success of assimilation. The US is a “melting pot”. People come from all over and, in a generation or two, they become Americans.

The problem with this claim is that it is both true—yes, there is an identifiable Americanism that draws folk in—and untrue. Not only do cultural patterns continue down the generations, there is no single American culture.

In his 1989 classic Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways, historian David Hackett Fisher identified four British-origin American folkways that continue to generate deep divisions in American politics. Journalist Colin Woodard has updated and extended the thesis. Both Fischer and Woodard argue that much of American politics can be understood as struggles between cultural groups.

The most intense such struggle was the American Civil War. But, as journalist Kevin Philips wrote in The Cousins’ Wars: Religion, Politics, Civil Warfare, And The Triumph Of Anglo-America, the American Civil War was the last (at least so far) of three civil wars—the English Civil Wars (now known as The Wars of the Three Kingdoms, 1639-1653), the American War of Independence (1775-1783) and the American Civil War (1861-1865). This history of violent struggle rather undermines the peaceful assimilation narrative.

In his recent Triggernometry interview, journalist Richard Miniter gives a very accessible account of US politics in terms of the four-way cultural divide outlined by Fischer.

As he points out, networks of people migrate, and people bring their cultural ideas with them. These evolve over time, but show striking persistence as patterns.

The trick with US Presidential politics is to get at least two, and ideally enough of three, of these cultures onside. In 2024, Trump got the Borderers (the Scots-Irish “Hillbillies”), the South (the Cavaliers) and enough of the Middle Atlantic/Midwest (commercial Quakers and other Nonconformists) onside (plus increasing numbers of African-Americans and Hispanics onside), and so defeated Greater New England/Left Coast (the Puritans).

Miniter also makes the excellent point that one can identify at least three African-American cultures—Southern US, Northern US, recent African migrants. I would divide them into in the descendants of American slaves (perhaps also then divided into Northern and Southern), Afro-Caribbeans and recent African migrants. Either way, culture trumps race. Trump’s inroads into the “African-American” vote has substantially come from recent African immigrants and Afro-Caribbeans.

Nor is cultural convergence the only possible pattern. Various commentators have pointed out that second-generation Muslim migrants—who have not experienced the problems of the societies that their parents left—are often more alienated/culturally distant from Western society than their parents.

Nonsense modelling

In We Wanted Workers, George Borjas sets out how chaotically complicated the US immigration system is, with some startlingly long waits for approval (p.56). He also reminds us of how utterly wrong projections about the effect of the 1965 legislative changes to American migration law were (p.57). Borjas juxtaposes two narratives: migrants-as-workers—fitting into migration-as-economic-boon narratives—and migrants-as-people, with a lot more inconvenient complexities.

Those open-border migrants-as-workers models that generate allegedly enormous economic gains from “the full liberalisation that hasn’t been tried” are, as models, neither true nor useful. Borjas points out that they do not include moving costs, nor a range of relevant considerations, and such moving costs must be quite high, as way fewer people migrate than could theoretically do so (Pp69ff)—a point that, as Kevin Erdmann has noted, also applies to internal migration.

As Borjas explains, such patterns:

…suggest that the potential migrant attaches a very high psychological value to the social, cultural and physical amenities associating with remaining where he or she was born, including family, friends and familiarity with old surroundings. It then takes a very large improvement in living conditions to justify the decision to move. (p.72)

Nobody with serious knowledge of the history of migrations would entertain the models generating such alleged enormous economic gains from open borders for a moment. It is worth setting out just how ridiculously inadequate such models are.

First, there is the problem of what Borjas calls robotic workers. That is, workers that are assumed to transact in identical ways and do not make inconvenient choices. Another way to make the same point is that humans are treated as undifferentiated “economic particles” in a Social Physics. This is just flatly false, as the above quote from the review article on behaviour varying by culture makes clear.

As military analyst Kenneth Pollack notes:

… until relatively recently, Western economics and management theory took as a bedrock assumption that universal factors such as the availability of technology and the profit motive would produce similar organizations and methods of operation in any business regardless of cultural factors. This has been challenged broadly by new studies of the impact of cultural preferences on organizations, management, and leadership, such as the massive Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) study of such practices in 62 different countries. The GLOBE study found that societal culture had a far greater impact on leadership, management, and organizational behavior than market forces and industry effects (i.e., industry-wide practices across societies). This and other such studies have increasingly demonstrated that, despite the Darwinian competition of the marketplace (akin to the competition of combat), organizations function very differently in different societies. They have found that this holds true even for businesses nominally owned by foreign entities, which have to take on the patterns of behavior of the host country to survive and thrive. (Armies of Sand, P.408)

Economist Arnold Kling is quite correct, economics should be the study of human interdependence, which is why countries and communities as just-places-where-transactions-happen is such an inadequate basis for analysis. Thus, when renowned economist Milton Friedman stated that:

There is no doubt that free and open immigration is the right policy in a libertarian state … (P.172)

his analysis was hopelessly inadequate, as is explored further below. He then added:

… but in a welfare state it is a different story: the supply of immigrants will become infinite.

That there are no movement costs in open border models is silly, though including such costs would then point to other problems with such models. Much more seriously, the open border models assume that all transactions are unproblematically scaleable, that the benefit of more people doing more transactions in a particular territory is linear in its consequences. There are no increasing marginal costs, nor decreasing marginal benefits, affecting the consequences of migration [other than those implied by standard labour supply and demand elasticities]. Something that Milton Friedman did not believe, at least not for welfare states.

The scale of migration is demonstrably a crucial factor in its consequences, whether or not the welfare state exists. Both scale in terms of overall level of migration and in terms of whether it is “large lumps” migration—as in Western Europe, the UK, the US, recently in Canada—or “small lumps” migration, as in Australia.

The models also assume that the advantages of a society are independent of its population—as they are undifferentiated robotic workers/economic particles. This has been classed as the “Magic Dirt” hypothesis—once migrants hit the “magic dirt” of the West, they will act like Westerners—but I would call it the perfectly resilient institutions hypothesis.

If you do not think resilience—the ability to deal with changes in circumstances—matters, then you are saying that all social arrangements are as resilient as they need to be and nothing you are proposing will adversely affect that. Yet another huge potential cost of migration is thereby completely ignored. It is very clear that allegedly equivalent institutions operate quite differently in different cultural contexts, so of course importing folk with very different cultures will affect how your institutions operate.

Moreover, mass migration can break polities. Economic historian Robert Fogel set out how mass migration broke the American Republic along its fault-line of slavery.

Lebanon was broken along its ethno-religious fault-lines by Palestinian migration. Jordan suffered a short civil war from Palestinian migration, Kuwait found that its Palestinian migrants supported the Iraqi invaders. None of these were welfare states.

When one looks at political decision-makers in history, it is striking how many of their decisions are about resilience, are about having arrangements that can cope with shocks and increase stability by making shocks less likely or smaller. Yes, improving efficiency is a persistent theme in policy, but so is resilience, and decision-makers often struggle with the tensions between the two. What is efficient is not alway resilient, and vice versa. Much of risk-management is about resilience, not efficiency. In We Wanted Workers, Borjas pushes back against economists’ worship of efficiency (Pp201-2).

The open border models also ignore distributional effects. Which is an analytical and moral nonsense. The distributional effects matter deeply for how people will react and for the social stability—i.e., the resilience—effects of what is proposed. It matters that migration typically transfers income and wealth from resident workers—albeit more by suppressing wages than cutting them—to migrants and holders of capital, plus to owners of land (via higher rents).

The last effect is aggravated as new people migrating in both increases the return on, and the pressures for, regulation to restrict housing supply and land use—the NIMBY (not in my backyard) effect. The combination of higher rents, inflated house prices and increased tax take being well-nigh irresistible. You can see the migration-fosters-restriction cycle in the UK, the Antipodes, Canada and the Zoned Zone US. California generated BANANA (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone), using restrictive regulation to extract rents from the tech boom, a process made both easier and more intense from migration. Jurisdictions that have largely avoided the effect—notably Texas and Germany—had pre-existing institutional barriers to going down that route.

Finally, the implicit or explicit notion that borders are arbitrary—so have no moral or appropriate-to-policy significance—is also nonsense. All polities have boundaries, they are all based on specific territories. It is such a universal pattern, it must have powerful reasons behind it.

States are providers of public goods. That is, goods that are non-rivalrous (the enjoyment of one does not impede the enjoyment of another) and non-excludable (folk cannot be blocked from enjoying the good if it is provided). Protecting and facilitating productive taxpayers enables states to extract revenue.

But public goods have an scope problem: whom do you tax and whom do you protect? The solution that both public and private providers of public goods come up with is to tax and protect a particular territory. In others words, they bundle public goods together in a specific territory, turning them collectively into a club good—a good that is non-rivalrous but is excludable. The bundle of public goods applies to residents of a particular territory and (in a more limited fashion) to citizens living outside the territory.

Thus, at the heart of the Holocaust was stripping Jews of any—or any functional—citizenship, thereby stripping them of a fundamental protection. Just as the most effective rescuers of Jews were diplomats, who could extend the protection of a state to them.

The protective role of the state shows up in the genetic record. The development of farming and animal herding (i.e., pastoralism)—so, contestable productive assets with increased population density—led to massive purges of male lineages in the Y-chromosome Neolithic bottleneck. This purge of male lineages was largely brought to an end by the development of chiefdoms and states, who had an interest in protecting those paying tribute and taxes. Though this was less so among pastoralist societies, as the mobility of animal herds—and protecting such mobile assets—meant that all free males were warriors, while there was no capacity to increase how productive grasslands were, creating both more binding resource constraints and more difficulty in taxing such assets. Hence, steppe states were essentially super chiefdoms rather than full states, with more brutal competition among male lineages than in farming states.

The borders of countries are “arbitrary” in the same sense that a property boundary is “arbitrary”. Yes, all sorts of boundaries are possible—they have no specific necessity to them—but that does not remotely make them morally arbitrary nor of other than great significance to human flourishing and good policy. The scope problem in funding and supplying public goods is real.

Creating (and destroying) institutional commons

States create institutional commons. That is, an interlocking structure of institutions that depend on the order—and the surplus—extracted, created (see below), and enabled by the state.

Like any commons, institutional commons have the problem of folk over-extracting from them and under-investing in their health and maintenance. Constructing and maintaining a resilient and efficient institutional commons is actually quite difficult.

That difficulty is at the heart of why countries vary so dramatically in their economic performance, and why such variations in performance are remarkably stable over time. Very different cultural, institutional and social equilibria are both possible, and realised. People do not remotely all have the same habits of mind, the same social traditions.

Yes, we are a normative species, as that generates the robust shared expectations that enabled the cooperative subsistence and reproductive strategies required to raise our biologically expensive children. But no particular sets of norms are required. On the contrary, variety in such enables adaptation to a wide variety of circumstances and so highly path-dependent mixes of the same.

Our Pan troglodytes (chimpanzee) primate cousins may be close to Homo economicus, but the ways we are not are key to our hugely greater capacity for productive cooperation. Our economic exchanges rest on us being far more normative than our primate cousins.

Any chest-thumping primate alpha male can do “mine!”. The real trick is default acceptance of “yours”. (A similar example of what really matters is that inventing the wheel does not have much import. It is the axle, and the domesticated herbivores to pull the wheeled vehicles with axles, that makes the difference.)

The millennia-long history of pre-modern frontier walls comes from farmers not being able to trust pastoralists to respect the farmers’ “yours”. What an effective state does is greatly expand the ambit of respect of “yours” in creating its institutional commons. This, along with the taxing by the state creating surplus—originally, by taking resources before they turn into supporting more babies—is why state societies are way more productive (in all senses) than stateless societies.

The aforementioned variance in the quality of institutions, and institutional commons, creates at least two blocks to the (otherwise) usable knowledge of good policy: (1) local institutional resistance, and (2) difficulties in translating that knowledge into a form that is locally resonant and effective—as patterns of behaviour, and so responses to incentives, vary by culture: often because how incentives are framed varies by culture. Such variance in cultural and institutional equilibria deeply affects how much—and for whom—trade raises incomes and whether wages equalise from increased trade.

We can observe the decay of such institutional commons in many countries, with increasingly dysfunctional South Africa being a particularly egregious example. Then again, an increasingly dysfunctional United Kingdom is also an example, if not yet anywhere near as bad.

One of the most difficult things in any political system is to create, and maintain, pro-social feedback mechanisms. The Blair-Brown Government (1997-2010) in the UK quite systematically broke existing feedback mechanisms, which the Tories then did nothing about; hence the UK’s amazingly, and disturbingly, rapid decline as the degradations of activism and the pathologies of bureaucracy became so little subject to effective checks.2 Meanwhile, China is beginning to parallel 1980s/1990s Japan to a remarkable degree, with the centralisation of finance in ways that distorted economic feedbacks being a major factor in creating some strikingly similar economic patterns (and commentary about the same).

An institutional commons is a common good or common pool resource: access to the institutional commons by citizens and other residents at large within the territory of the state is generally not excludable,3 but much of what is provided is rivalrous. Moreover it is a created common pool resource. It can be built up; it requires patterns of adherence and support; it can be drawn down.

Hence, states historically have put a lot of resources into generating various levels of commitment to the polity. The use of norms, rules, rituals, to generate robust shared expectations is crucial to both the functioning—and the resilience—of polities because they require a robust institutional commons. This is true even of—in some ways particularly for—exploitive political orders. There is a reason that autocratic—and particularly totalitarian—states invest so much in grand rituals of loyalty and conformity.

Universities across the West—and Anglosphere Universities in particular—are pumping out systematic attacks on the heritage of their societies: a key social “glue” for any institutional commons. Indeed, precisely because contemporary progressivism is so much the politics of the unaccountable classes4—who can pump out toxic ideas because they do not face strong enough reality tests (because unaccountable)—many progressive policies and projects degrade the institutional commons of Western societies (or, in the case of progressive-run cities in the US, the local institutional commons). The (predictable) surge in homicides from the BLM anti-police activism was a particularly egregious case in point, though disastrous pandemic policies emerging from the unaccountable classes are also strongly implicated.

The New York Times’s The 1619 Project is a quite systematic attack on the institutional commons of the United States. Much of what comes from the universities—and is transmitted through activist networks (including activist media)—is quite deliberately socially corrosive, operating on the basis of the social alchemy theory underlying a lot of Critical Theory and its derivatives—the notion that the righteous thing to do is to burn away the “base metal” of the “oppressive” order so the “gold” of social transformation will emerge from it.

Much nonsense has also been written about citizenship being “morally arbitrary”. Citizen is no more arbitrary than property owner is. All that effort put into generating a loyal and committed citizenry is very far from irrational. It is simply condescending, arrogant, ignorance by Theory-mad Libertarian—or Critical Theory-derived (“woke”)—Folk of System to think, or imply, that it is. Trying to dismiss borders or citizenship as morally arbitrary is a manifestation of hyper-norms: norms that trump all other considerations, even practicality or the basic structure of things, but are very useful for rhetorically grand status-plays and power-grabs.

The Libertarian pushing of ludicrously inadequate understandings of the social dynamics of migration has also been a corrosive attack on the institutional commons of Western societies. A high level of congruent, socially-positive, expectations within a society is central to creating a resilient institutional commons, which migration in the UK and Western Europe is patently undermining.

Indeed, the open border models are so ludicrously inadequate, of such studied unreality, they must be classed as propaganda—as activism parading as scholarship—not serious scholarship and no activist scholarship should receive any taxpayer funding. For the failures of academic incentives—and academe’s inadequate reality-tests—are not specific to any particular intellectual tradition. Authoritarian and totalitarian regimes of all forms—from Nazism to Communism and beyond—have been able to cite plenty of academic writings to support their ideologies.

Continued in the next post.

References

Patricia Balaresque, Nicolas Poulet, Sylvain Cussat-Blanc, Patrice Gerard, Lluis Quintana-Murci, Evelyne Heyer & Mark A. Jobling, ‘Y-chromosome descent clusters and male differential reproductive success: Young lineage expansions dominate Asian pastoral nomadic populations,’ European Journal of Human Genetics, January 2015. https://www.nature.com/articles/ejhg2014285

George J. Borjas, We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative, W.W.Norton, 2016.

Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith, Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Migration, First Second, 2019.

Michael A. Clemens, ‘Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 25, Number 3, Summer 2011, 83–106. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.25.3.83

Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, W.W.Norton, [1989], 1994.

David Frye, Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick, Faber & Faber, 2018.

Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited,’ Sociological Theory, Vol.1, 1983, 201-233. https://www.csc2.ncsu.edu/faculty/mpsingh/local/Social/f15/wrap/readings/Granovetter-revisited.pdf

Joe L. Kincheloe, Critical Constructivism, Peter Lang, [2005] 2008.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800-1830, Volume 1: Integration in the Mainland Mirrors, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels, Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800-1830, Volume 2: Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia and the Islands, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Glenn C. Loury, The Anatomy of Racial Inequality: The W.E.B Du Bois Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2002.

C.F. Martin, R. Bhui, P. Bossaerts, T. Matsuzawa, & C. Camerer, ‘Chimpanzee choice rates in competitive games match equilibrium game theory predictions.’ Scientific Reports, 2014, 4, 5182. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep05182

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Zvika Neeman, ‘Geography, Transparency, and Institutions,’ American Political Science Review, June 2017, 111, 3. 622-636. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/workingpapers/2016/twerp_1129_moav.pdf

Joram Mayshar, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, ‘The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?,’Journal of Political Economy, April 2022, 130, 1091-1144. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356707920_The_Origin_of_the_State_Land_Productivity_or_Appropriability

Tommaso Nannicini, Andrea Stella, Guido Tabellini, and Ugo Troiano, ‘Social Capital and Political Accountability,’ American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2013, 5 (2): 222–50. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.5.2.222

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge University Press, [1990] 2011.

Kevin Philips, The Cousins’ Wars: Religion, Politics, Civil Warfare, And The Triumph Of Anglo-America, Basic Books, 2000.

Kenneth M. Pollack, Armies of Sand: The Past, Present, and Future of Arab Military Effectiveness, Oxford University Press, 2019.

Jeffrey D. Sachs & Andrew M. Warner, ‘Economic Convergence and Economic Policies,’ NBER Working Paper 5039, February 1995. https://www.nber.org/papers/w5039

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, The Bodley Head, 2010.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, HarperCollins, 2016.

Logan Wright, ‘China’s Economy Has Peaked. Can Beijing Redefine its Goals?,’ China Leadership Monitor, Fall 2024, Issue 81, September 1, 2024. https://www.prcleader.org/post/china-s-economy-has-peaked-can-beijing-redefine-its-goals

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck,’ Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04375-6

There are no such thing at Trans folk in the “gender soul” sense that Queer Theory and Trans activism invokes. There are people with various levels and forms of alienation from the cultural expectations of their gender—tomboys; sissies; future gays and lesbians—and various levels and forms of alienation from, or tensions with, the (sexed) physicality of their body (which can include sexually-charged alienation or tension). The adolescent forms of alienation usually pass, if folk are just let be. People can find a gender non-conforming child confronting, hence “Transing the gay away”. The notion that the appropriate response to a gender non-conforming child is to hormonally and surgically mutilate and sterilise them is evil nonsense. Unfortunately, it is very well funded evil nonsense that helps the socially-imperial welfare state apparat undermine parental authority.

The rapid decline of the universities also represent the interaction of the degradations of activism with the pathologies of bureaucracy, aggravated by the downsides of feminisation in institutional milieus with poor reality tests and inadequate accountability pressures colonised by sets of ideas that actively block reality tests and accountability.

Prisons, labour and concentration camps are mechanisms of exclusion. So are various (other) forms of segregation and discrimination.

Richard Miniter defines the accountable classes as all those whose income depends on their performance and the unaccountable classes as those who are paid for turning up. As he points out, the Tech bros/Silicon Valley shifted away from the Democrats when they came to realise that the unaccountable classes were their enemies. The corrosive effects of DEI on organisational effectiveness; as well as the end run around the First Amendment—and particularly the de-banking—lawlessness of the Biden Administration made that very obvious. (The systematic gaslighting of the American people over the cognitive decline of President Biden did not come from nowhere.)

Always impressed because you are always able to hit the nail directly.

The context that led to the surge in open-borders economics was that free trade was supposed to lead to an equalisation of wages between countries based on significant increases in income

Free-trade doesn't mean open immigration between nations. Free trade means that goods move across borders without taxation or tariffs. If your best and hardest workers aren't in your country, how can you have any type of trade?

They had a hypothesis—free trade would equalise wages across countries. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) provided a test of the hypothesis. The hypothesis was proven untrue.

I live in Texas and I've been watching this for 30 years. If you want to increase wages, you need to increase the means of production. That means US businesses putting factories in Mexico and South America. Instead of fostering growth on our own continent, we pushed those factories into China.

When the evidence was unhelpful, they doubled down on their Theory. Just as the grotesque failures of Marxism has generated endless versions of “real Communism hasn’t been tried” here was “real (market) liberalisation hasn’t been tried”.

Marxism always works as intended. The mass starvations, gulags, re-education, loss of productivity and loss of wages is a feature, not a bug. Marxism is meant to fail.

Being a Person of System has at least two great appeals. First, it potentially provides the basis for wielding a great deal of power over one’s fellow humans.

That is why Marxism/communism always works as written. It gives a great amount of power over everyone else. That's not a bug, it's a feature. It's why communism always fails spectacularly.

Second, it elevates one’s moral and cognitive status: one can dismiss those who reject your System,

Has anyone else noticed that the ongoing rant is "Our democracy," as if their democracy is different from general democracy.

…suggest that the potential migrant attaches a very high psychological value to the social, cultural and physical amenities associating with remaining where he or she was born, including family, friends and familiarity with old surroundings. It then takes a very large improvement in living conditions to justify the decision to move.

If you move someplace to improve your life, why bring all those troubles with you? If a place is better, changing it to where you are from doesn't work. You might as well have stayed home.

One again, from a Texas perspective. I've worked with green card immigrants. They work hard, they learn the language, they follow the laws, and when they get permanent citizenship, they are the most pro-American people I've ever seen.

This has been classed as the “Magic Dirt” hypothesis—once migrants hit the “magic dirt” of the West, they will act like Westerners—but I would call it the perfectly resilient institutions hypothesis.

If this were the case, migrants hitting the shores would instantly learn the language, follow the laws, and be good citizens. But they don't, not always. Some never learn the language, and some don't obey the laws, and some stand at protests waving the flag of the country they came from.