How China did it

On Acknowledged Possession (5)

Some time ago, I was intrigued by how China managed to have a massive commercial take-off well before it legalised private commercial property (in 2004). I therefore wrote a 12,000 word essay on the origins and dynamics of property. That is far too long for a Substack post, so I have broken it up into a series of posts.

The first post established that property predates the state or the law. The second post examined how property could operate outside—or even against—the law. The third post looked how pervasive conventions are, the uses of law, pacification, and different institutional paths. The fourth post covered owning people and animals plus regulation as the control of attributes of owned things. An interlude post looked at why the Great Enrichment—the shift from mass poverty to mass prosperity—started in Great Britain. This fifth and final post seeks to answer the original question of how China did it.

It is useful to distinguish between the level of commerce (buying and selling goods and services, whether produced by yourself or by others) and the level of trade (any exchange of goods and service, especially over distances). Command economies—which existed well before modern Communism—engage in trade while supplanting or repressing commerce. As rulers—and their agents—were often major participants in trade, pacification could drive up the level of trade more than it did commercial activity.

When China was unified, the Emperor would be the world’s largest international trader, through the exchange of silk for horses. Some of these exchanges were vast, involving tens of thousands of horses and over a million bolts of silk (Beckwith, p.22).

But the Son of Heaven could clearly not be a mere merchant, despite a considerable amount of imperial revenue coming from the Emperor’s salt monopoly (along with—depending on the period—tea, alcohol and perfume monopolies). So such silk-for-horses exchanges were presented as the Son of Heaven making gifts of silk and receiving tribute of horses. At least some of the Chinese tributary system operated as a congenial re-characterisation of the trading activity of the Emperor and his agents. Some of such also was a conduit for commerce, both Chinese and foreign.

Since Chinese emperors were dynastic autocrats, they operated as sole proprietors of their monopolies. They sought to maximise returns and minimise costs, including managerial costs. Under an attentive emperor, their monopolies could be quite operationally efficient.

Moreover, it was the sale of the products of the monopolies that generated revenue. This gave Chinese emperors an interest in flourishing exchange. One could reasonably argue that—especially given administrative limitations—such imperial monopolies were more favourable to flourishing economic activity than an equivalent tax regime would have been.

It is also clear that administrative simplicity was a major consideration in what taxes were levied. Indeed, across civilisations, simplifying taxes and expenditure was often a major motivation for rulers in encouraging monetisation.

To recap earlier discussion in these series of posts, elevating the frequency and scale of exchange—and production for the same—is the core economic benefit of effective systems of legal property rights. Clarity of property rights—of rights-to-decide-over-what—ease of adjudication, and reliability of their protection, all lower transaction costs, potentially dramatically.

Transaction costs are costs entailed in making an exchange or other interaction. Specifically, they are search and information costs; bargaining and decision costs; policing and enforcement costs. Transaction friction is the degree or rate at which transaction costs impede transacting. (Money is a highly effective transaction-friction reducing mechanism, hence why societies keep evolving some form of it.)

The haggling and information hoarding that is a feature of bazaars arises from the patterns of dealing in hand-made goods and the significance of intensely personalised connections for flows of information and trust. Conversely, conventional mechanisms such as hue-and-cry work much more poorly in a world of standardised, machine-produced items than they did in one of hand-made (so more distinctive) items. Hence mass production and modern policing arose in tandem.

Commerce generally aims to reduce transactions costs, to seek ways of exchange with the least transaction friction. Indeed, commerce tends to reduce inefficiency: to find resources currently “locked up” and make money by releasing them for wider use. Motivated discovery is a major factor in commerce.

This is in stark contrast to bureaucracy, with its incentive to accrue resources to itself, adding to the expense (and inefficiency) of processes. If bureaucrats are paid to complete processes, then they have an incentive for such processes to continue indefinitely or, even better, expand. Hence bureaucracy can easily profit by increasing transaction friction, by people being forced to deal with it.

This is especially true if bureaucrats can then sell official approval. As is discussed in the second post in this series, corruption is the market for official discretion. The more official discretions there are, the larger the potential market for corruption.

President Xi Jinping is attempting to simultaneously increase Chinese Communist Party (CCP) control over, well, everything while rooting out corruption. He is thus increasing the potential value of CCP-official discretion while attempting to crack down on the sale of it. This is, fairly clearly, a losing game—hence the apparently endless purges.1

The tendency of bureaucracy to hoard authority—including seeking to de-legitimise other forms of action or sources of information—and to evade the complexities of competence, can also lock-up resources and increase transaction friction. Avoiding state-generated transaction frictions is why informal exchange—using the conventions of property and exchange while evading state authority—happens within, and across, the territories of states and can grow into extensive networks.

The lower transaction costs are—including the lower the risks involved in transacting and in having assets, plus the greater the clarity in who has what rights and claims—so the lower the level of transaction friction, the higher the scale of transactions are likely to be and the more willing people are going to hold, and invest in, commercial assets at scale. The state-revenue and economic growth advantages of this situation are likely to be very large.

Thus, the biggest single factor in explaining the difference in economic trajectories between Latin America and Anglo-America is that state action in the former imposes high transaction friction through complex, time-consuming and expensive property use, registration and transfer rules compared to the latter. Consequently, the scale of transactions—so economic activity—has been systematically greater in Anglo-America across centuries, with large (compounding) effects. It is also why the informal sector is so much larger in Latin America than in Anglo-America.

While the advantages of the reduction of transaction friction through an effective legal system are very real, this is—as we have also seen in earlier posts in this series—very different from stating or implying that such a happy situation is required for commercial activity to occur. It is perfectly clear—from history and anthropology—that such a well-functioning system of property law is absolutely not necessary for commercial activity, even considerable levels of commercial activity. Hence, as economist Douglas Irwin notes of the economic scholarship on property rights:

A regular finding is that informal norms are more important than formal rules in protecting property

As, of course, the case of black and other informal markets starkly demonstrate.

Property established by conventions of mutual acknowledgement—whether or not such is formally ratified by the state—can in themselves support considerable levels of commercial activity. Especially if agents within the state provide functional acknowledgment of property, even if formal ratification is lacking and their acknowledgement is merely passive acquiescence.

The single biggest benefit that a state can provide to encourage people to transact is pacification, is providing a sufficiently peaceful social order. The Chinese economic take-off after 1978 happened in a state well able to impose social order.

The social returns on pacification are large. But a state that can pacify can also predate. The state as protector and predator creates the paradox of polities or the paradox of politics, famously enunciated by the first and greatest historical sociologist, ibn Khaldun (1332-1406):

Mutual aggression of people in cities and towns is thus averted by the authorities and by the government, which hold back the masses under their control from attacks and aggression against each other. They are thus prevented by the influence of force and governmental authority from mutual injustice, save such injustice as comes from the ruler himself. (Muqaddimah, I:2:7)

Principles of China’s reform

In 2002, Chinese economist Yingyi Qian published a very revealing working paper (later expanded into a book) on the post-1978 Chinese economic take-off. When examining that take-off there is both the public, and the surreptitious, story—what was happening “under the hood”.

The early stages of economic commercialisation were not supported by the Party. But the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) had so disrupted Party control in the countryside, that the CCP found itself fighting a losing battle against peasant-driven de-collectivisation and commercialisation. In the Chinese countryside, the old patterns of avoiding entanglement with the State re-asserted themselves. Over the post-1978 reform period, the CCP shifted from resistance to acquiescence to active embracing of commerce—provided its dominance was never threatened.

It is clear from the scale of prosecutions for commercial activity—all of which were then illegal—that, even during the Cultural Revolution, there was a lot of commercial activity happening, despite the collectivisation of productive assets and commerce being illegal. This was the operation of property, and exchange, against the state, as discussed in the second post.

The implication of this was that, if the Chinese Party-State simply stopped repressing commerce, some level of commercial take-off was likely. This was especially so given China’s long history of people finding ways to avoid entanglement with the legal apparatus of the state, including its courts, while engaging in extensive commerce, manifesting the power of the conventions of property and exchange. This systematic avoidance was very different from Europe’s institutional development (or, for that matter, Japan’s).

While private commercial activity was not fully legalised until the 2004 Constitutional Amendments, starting in 1988, a sequence of such Amendments signalled the increasing official tolerance of private commerce. Yet, even before 1988, there was already considerable economic take-off and commercialisation.

Economists examining how to achieve economic take-off have typically worked back from what the most historically successful did (or at least apparently did). This ignores differences in starting points—both cultural and institutional. As Prof. Qian notes:

the real challenge of reform facing transition and developing countries is not so much about knowing where to end up, but about searching for a feasible path toward the goal.

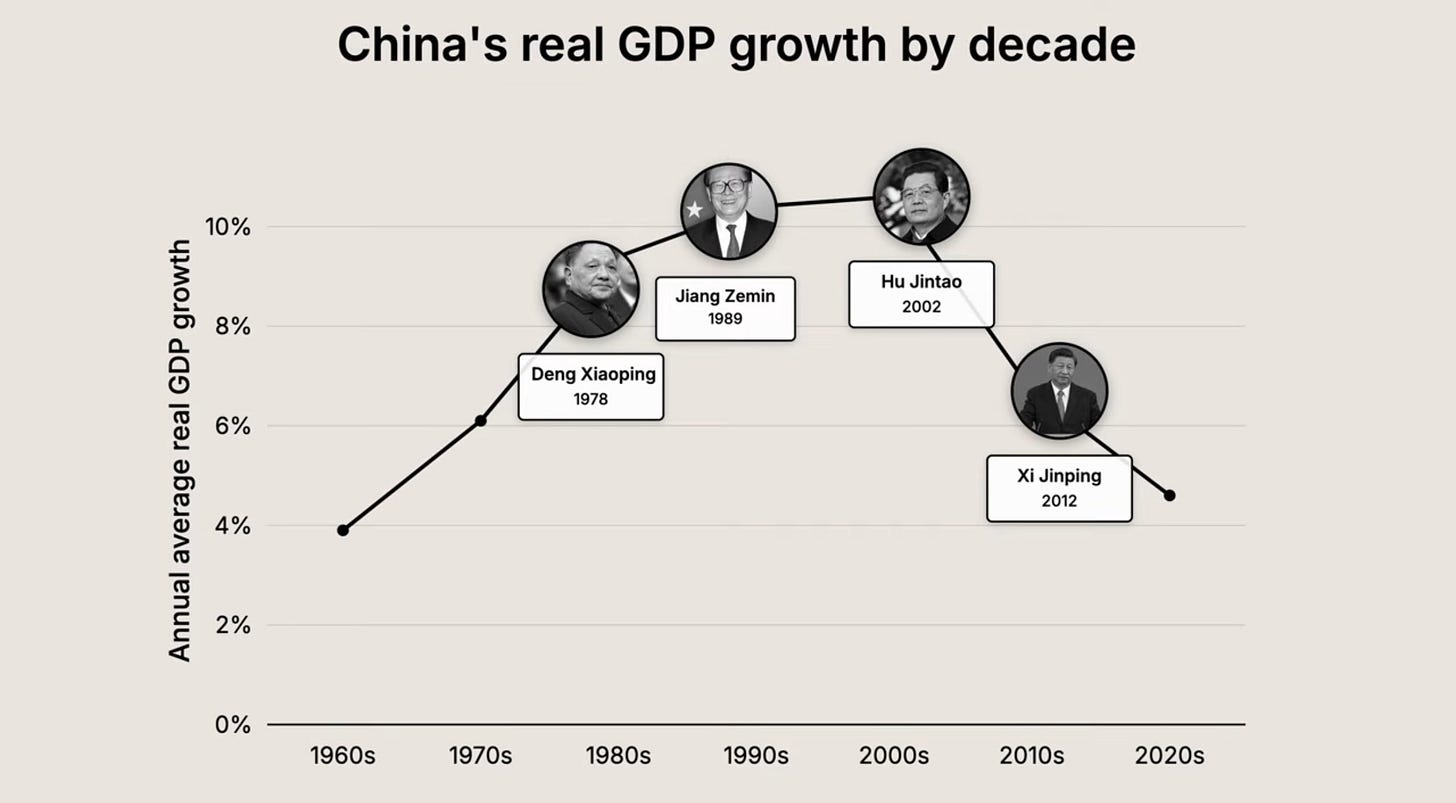

A key insight of Yingyi Qian is that the more inefficient your starting point, the wider the range of what might work to improve economic efficiency—that is, will get more out of what you have. The corollary of this is, economic gains will tend to get harder over time, once the “easier” gains have been made: a pattern that is clear in China’s post-1978 economic trajectory.

The central principles of the post-1978 reforms in China were (1) no losers and (2) align incentives. For instance, the plan continued, but a price-driven, increasingly commercialised, sector was added on. The more successful the latter became, the more the former could be phased out. This was “dual-track” pricing: plan plus market. The switch to requiring a set amount of produce from farmers, they could keep the rest, essentially created a lump-sum tax with zero marginal taxes on their further production.

The other successes were Town-Village Enterprises (TVEs), Fiscal Federalism, and anonymous banking. By devolving a lot of decision-making to local areas, allowing local governments to keep a substantial part of increased revenue, and promoting officials according to economic performance, the capacity and incentive to discover what worked was greatly increased. It also meant corruption tended to work with commercialisation and economic growth, rather than against it.

Anonymous banking, by making private finances opaque to the state, limited predation by state actors. This gains extra poignancy with the rise of de-banking in the West, particularly under the Obama and Biden Administrations.

One of the very strong patterns of history, is that the more transparent to the state economic activity is, the easier it is to tax (or otherwise predate upon). That agricultural production in the Nile valley was highly predictable—the soil was of standard quality and all water came from the annual flood—enabled the state (Pharaoh and Pharaoh’s agents) to dominate resource extraction and allocation. Similarly, the development of the modern factory/workplace/firm made it much easier for modern states to tax economic activity (particularly income).

Feedback systems

The clear failure among the post-1978 policy changes in China was the attempted reform of the State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Even the economically reforming “engineering state” of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has failed to find a way to make public sector production match the economic efficiency and dynamism of commercial production.

A good social feedback system generates and uses information by turning information into incentives, and incentives into information, in a pro-social way. Central planning destroys, suppresses, and fails to use, relevant information. This both creates, and is aggravated by, poor incentives, creating profoundly inadequate feedback systems.

The price mechanism of commercial exchange economises very efficiently on information but—even more to the point—it turns available information into incentives, and incentives into information, to create value: including by active searching for value-creating opportunities, while the operation of loss and bankruptcy steers resources away from value-destroying activities. China managed to use commerce to progressively replace central planning.

Value is not an intrinsic quality but represents the interaction of human judgements of (positive and negative) significance with some particular set of constraints and opportunities. Hence the economic calculation problem—the importance of the interaction of information and incentives for how well any economic system operates.

Managers of State-Owned Enterprises typically get little benefit from successful discovery, but are likely to suffer if they try something that does not work. The safest thing to do is to follow the set processes. Such processes will not, in any strongly responsive way, reflect the interaction of information and incentives that expands (or even maintains) value.

An attentive dynastic autocrat—supervising a small number of commercial monopolies—can hope to achieve efficient production. This is not a mechanism that is reproducible at scale.

During his rule of the Soviet Union, Stalin used competing information flows—Party, Government, Secret Police, all reporting to him—along with purges that broke up local cliques, as information and control devices. Thus, he could squeeze far more out of the smaller population and territory of the Soviet Union for his purposes than Tsar Nicholas II could for his out of a larger Russian Empire.

Even Stalin, however, could not generate high quality production at scale. Thus, the much-famed T-34 tank was somewhat mechanically unreliable and part of why the Soviets valued British and American trucks, rolling stock, etc that they received en masse during the Great Patriotic War was that it was much more mechanically reliable than their own stuff. Without the purges, and the economic surge that comes from shifting peasants to factories, the patterns of corruption, stagnation and increasing dysfunction asserted themselves as the years passed. (Gorbachev sacked officials at a similar rate to Stalin’s removals of officials: it did not save the Soviet economy.)

The problem with the State-Owned Enterprises was that they were State-Owned Enterprises. As this was not a status that the reform process in China was willing to change, the SOE reforms failed.

How to China a Great Enrichment

China was confronting two problems in 1978. (1) How to make its economy much more efficient. (2) How to update its technology—both physical and social. With the latter, it had the advantage that lots of countries had, by that stage, moved from the mass near-subsistence living which is normal in human history to mass prosperity. Moreover, in Hong Kong and Taiwan, China had prosperous and mercantile Chinese-population neighbours whose capital and expertise could be tapped.

Even more basically, the technology already existed. It could be adopted and adapted. As noted above, “catch up” economic growth when you are a long way from the production-possibility frontier is a lot easier than “new discovery” economic growth when you are at the production-possibility frontier.

So, the problem for 1978 China became to synergistically improve efficiency while adopting and adapting available technology. Some foreign investment; some sending people abroad to learn; some negotiating tech transfers, enabled the latter. (Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) can be over-hyped, as key decision-makers are not embedded in local concerns and connections.) Improving efficiency required aligning incentives towards increased efficiency.

The two principles that Yingyi Qian identified of (1) no losers and (2) align incentives, became crucial. No one was motivated and able to veto the take-off, except in the SOEs. The SOE reforms failed for the normal reasons public sector firms are comparative failures—they could not positively align information and incentives sufficiently and there were folk motivated and able to veto change: so the two reform principles Prof. Qian identifies did not apply.

The CCP had an extra reason to avoid creating losers. It was Communist. It was very easy for potential losers from market-oriented, commercialising reform to cite the ideology of the Party itself if they wanted to veto change. The no-losers principle minimised the incentive to block change (except in the SOEs).

Creeping commercialisation

A large part of the story, particularly early on, was creeping commercialisation simply from the CCP increasingly not even attempting to repress commerce. This came to be reinforced by the sequence of Constitutional amendments from 1988 on that increasingly signalled CCP acceptance of private commerce, culminating in its full legalisation in 2004.

This was a process where functional property rights were morphing into legal property rights. Various state actors were also becoming officially involved in commerce via the Town-Village Enterprises. Over time, many of these enterprises were themselves privatised.

Post-1978 China demonstrates that such acknowledgement within the state apparatus can be sufficient to engage in commerce at scale even though private commerce and ownership is formally illegal, as it was in China until 2004. Especially as the Party-State —due to the fraying of its local control due to the disruptions of the Cultural Revolution—had already proved itself unable to stop village-level commercialisation.

China in the period 1978-2004 was not so much a matter of black markets—the state was at first failing to, and later simply not, enforcing its bans on private property and exchange in anything remotely resembling a systematic way. It was more informal markets becoming increasingly formal over time. Markets whose existence and exchanges were formally banned, but functionally permitted: grudgingly at first, but then more actively.

That such markets could operate at all points to the key role of mutual acknowledgement in functioning property and exchange systems. It shows the power of conventional (or economic) property rights even in the absence of legal property rights.

Culture and convention

The fact that anyone of us can walk into a market, a shop, a bazaar, anywhere in the world and proceed to apply the conventions of property and exchange that operate across human societies has misled many economists in two ways. The first is that very unspoken ubiquity led many to not fully notice that property is pre-law, is pre-state, so to underestimate how important functional—rather than formally-recognised—rights-to-decide are. Black markets, the simple concept of illegal possession, show the importance of functional rights-to-decide due to (pre-law and pre-state) conventions of property and exchange.

The second error is—precisely because of the ubiquity of the conventions of property and exchange, and how powerful profit-and-loss commercial incentives are—to over-estimate the commonality of human motives. Because we humans cognitively model significance, not facts, the further we move away from the basic incentives and conventions of property and exchange, the more those judgements of significance are likely to diverge between cultures. This applies particularly as we move away from exchange to connections and to insider/outsider interactions. Transnational corporations have discovered that culture matters for their internal operations (which, of course, are all about connections).

We cannot neatly separate culture from incentives, as cultures generate varying judgements of significance, so varying incentives. That is why people from different cultures will make different judgements—and so act differently—in the same circumstances. Because they are NOT cognitively the same circumstances, as the maps of meaning being applied differ. For instance—due to different history, institutions and culture—Russians and Westerners look at politics very differently.

When looking at the apparently astonishing levels of welfare fraud in Minnesota, the Somalis involved were just acting like, well, Somalis—people from a highly clannish and collectivist culture who sharply differentiate between in-group and out-group. There is a reason there is such a striking correlation (0.91) between how collectivist a culture is and how corrupt the state is.

The problem in Minnesota was—as it so often is in the contemporary West—the systematic mismanagement of mass immigration by the resident political, media and bureaucratic elite, leading to the undermining and corrupting of American institutions by people with an incompatible culture.

The wider patterns of mismanagement of mass immigration are aided by the tendency of mainstream Economics—with its utility-maximising, complete-rationality paradigm—to default to treating people as interchangeable widgets, as “social particles”, thereby ignoring or trivialising cultural differences.

The biggest single failure of liberal universalism is to fail to understand how much liberal societies rest on evolved norms that are not remotely shared across cultural groups. Successful local adaptation is crucial to economic and other development: as China itself is a prime example of.

People do not become good liberal citizens merely by being translated to some “magic dirt” in liberal societies. Even less do they do so because occupying forces attempt to wave liberal policy-transformation wands and hand-outs.2

Understanding how patterns of connection and deference work in rural China to manage interactions without the involvement of the state does much to explain how peasants could de-collectivise and commercialise from below once the Cultural Revolution had disrupted CCP control of the countryside. That long history of avoiding entanglement with the organs of the state, and using accepted conventions to manage interactions, mattered. The ubiquity of the conventions of property and exchange interacted with Chinese traditions, and the disruptions of the Cultural Revolution, to produce expanding functional commercialisation well before the shift to formally-recognised commercialisation even began.

Prospects

As discussed in the second post, command economies—given their profound incentive and information problems—tend to generate both grey and black markets. Such adjustments to, and exploitation of, the limitations of command economies readily emerge via the conventions of acknowledged possession.

It turns out, that if you have a Cultural Revolution that massively disrupts the local reach of the Party-State, new social and economic possibilities emerge. A Leninist state can then preside over a massive surge in commercialisation. It remains unclear how stable a political equilibrium a Leninist Party-State with mass commercialisation is.

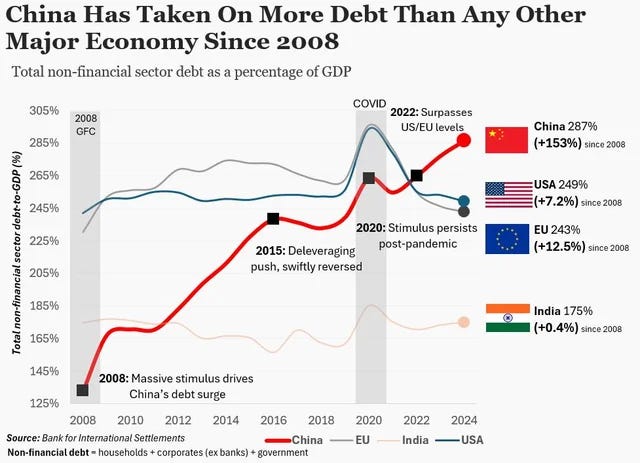

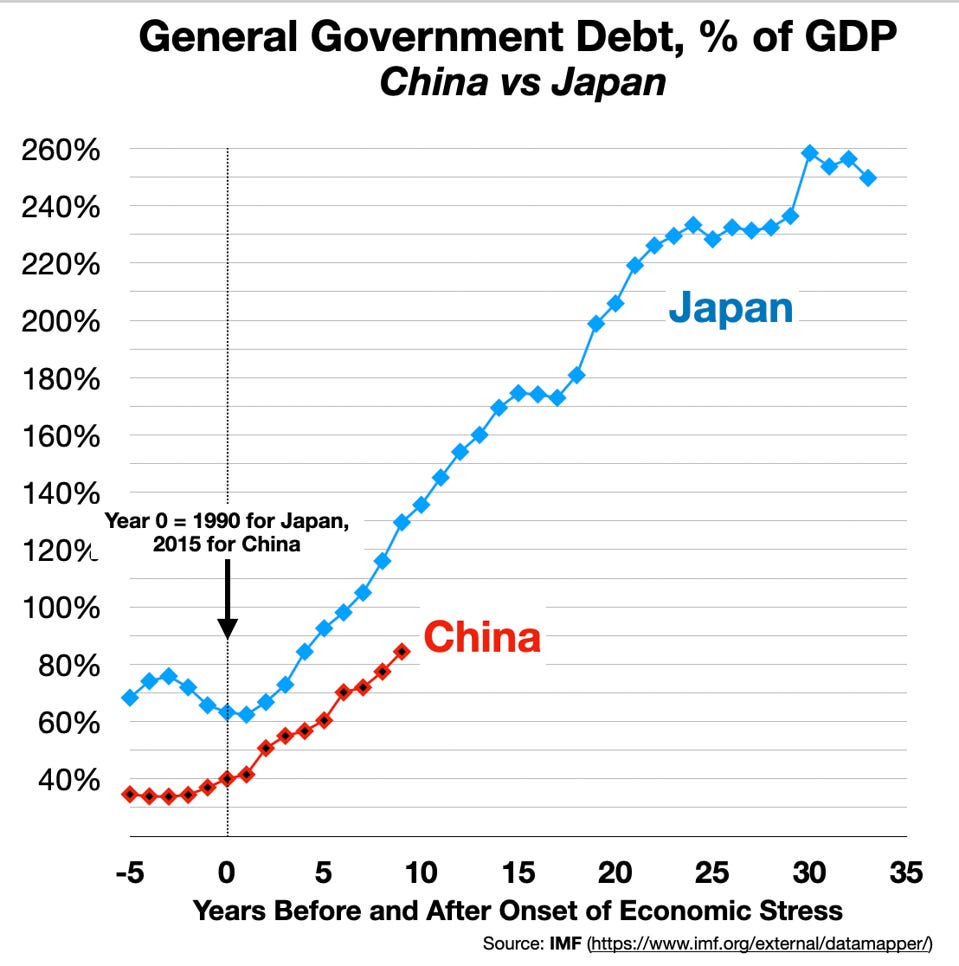

What is a little startling is how much China is currently replicating Japan after the c.1990 collapse of Japan’s “bubble” economy. Both Japan and China had dramatic growth surges. Both had an interestingly pragmatic—even exploitive—approach to foreign investment. Both became the second-largest economy in the world. Both Japan and China fuelled that with centrally managed financial repression (suppressing interest rates and directing lending). Both had massive property bubbles that collapsed. Japan lost a bundle on its overseas investments. China has the dubiously performing assets of its Belt and Road Initiative. Both had huge debt overhangs. Both had fertility collapses.

Japan then went into the “lost decades” of economic stagnation. But Japan did that as an already a highly developed, wealthy, mass-prosperity country with a political system that has strong feedback mechanisms. China is still a middle-income country and Xi Jinping has been busy doing the autocrat thing of suppressing feedbacks and having no clear succession mechanism. This in a China where there is already considerable scepticism about the reliability of its statistics and so how large its economy actually is.

You look at a very populous country of highly educated people, adopting learning-by-experiment at scale, able to pull off a massive surge in commercialisation, building up huge cheap energy capacity, with considerable cultural confidence, and the positives are clear. And yet, even Japan slid into economic stagnation. It is unclear that the CCP Party-State can do better, even with the technological dynamism it is now displaying (which, btw, Japan still displays).

The trap of Communism

It is precisely because Marxist Theory does not value the coordination, discovery and risk-management roles of commerce—and that command economies have serious information and incentive problems—that the Communist attempts to replace commerce have been such failures. Conversely, Communist Parties that have let commerce happen have presided over dramatic economic take-offs.

Geopolitically, Communism—that is, Marxism as operationalised by Lenin—was the best thing that ever happened to the US, as it crippled the two countries which had the most potential to rival the US: Russia and China.

That Marxism was a disaster for Russia and China is obvious from the historical record. Apart from the demographic, cultural and scientific devastation that Marxist regimes have unleashed on their own countries, the comparative prosperity experiment has been run repeatedly: East Germany to West Germany; North Korea to South Korea; Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan to pre-1978 China.

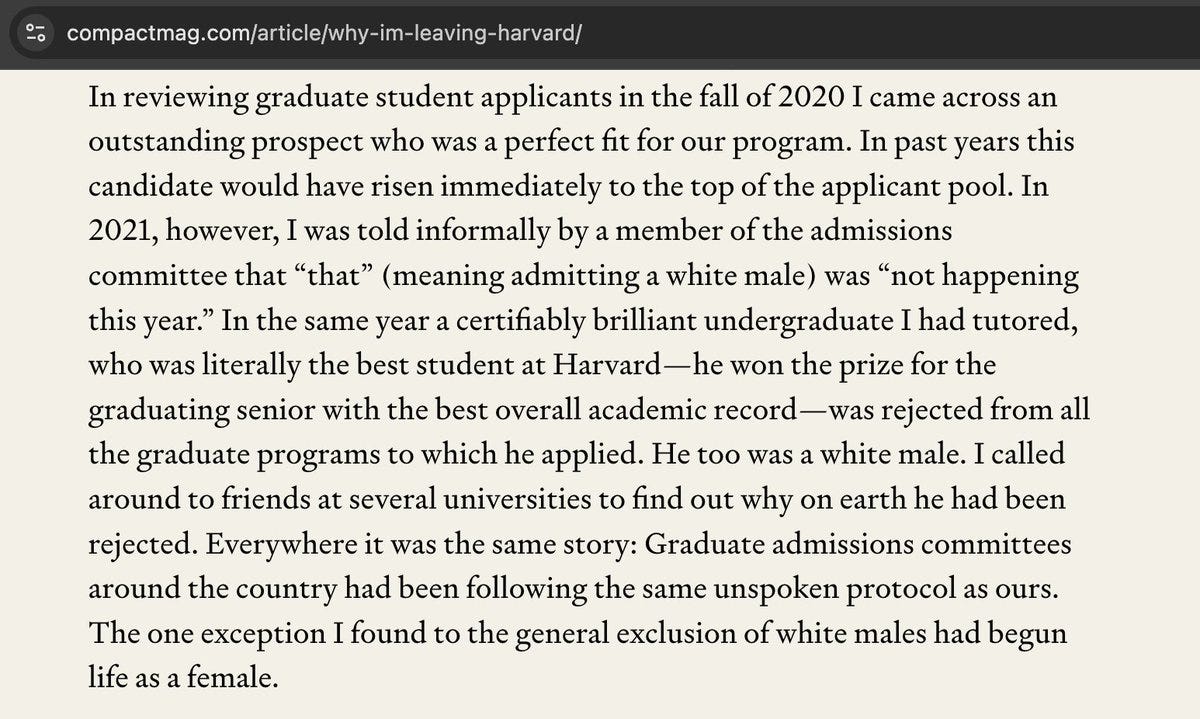

Both Russia and China would be more populous, more prosperous, more scientifically and culturally dynamic, if they had never had Marxism inflicted upon them. Yet ideas, derived in large part from Marxism, are now more influential in the US than they have ever been—remembering that “woke” is the popularisation of Critical Theory, and Critical Theory is derivative from Marxism.

Moreover, in their updated form and mode of operation via networks of activism—rather than via some centrally-directed Party—these ideas are increasingly institutionally degrading the US and the other Western democracies via the mad ambition to redistribute status. So, such networks are doing a new version of cultural, discourse and institutional degradation that Marxist ideas had previously done to Russia and China.

If you think that is overstated, networked Zhadonivism has been creating a vicious conformity in the arts and literary fields. Such intolerant zealotry has been spreading: into comedy, advertising, workplaces, schools, universities, professional associations, media, journals, sport, fiction, entertainment, games, hobbies … . Activist Lysenkoism has been corrupting science publishing in service of genderwoo and other Critical Theory spinoffs.

The first three states to adopt some version of DEI were the Soviet Korenizatsiya program; Mao’s so-called Black and Red identities; and North Korea’s Songbun system. Activist DEI commissars (aka diversity officers, bias response teams, sensitivity readers, intimacy consultants …) have been operating on the inquisitorial principle that error has no rights and they can determine error while generating “training” that is often not much more than struggle sessions. Diversity statements are used as norm-loyalty recruitment-screening devices. The US, and the West generally, has been afflicted by activist-networked versions of classic Leninist—i.e. operationalised Marxism—social control mechanisms, justified by Critical Theory derivatives of Marxism.

Elite vetoes

As we have seen, the key thing in Britain’s original economic take-off—and China’s post-1978 economic take-off—was that no-one was able to veto the take-off. In both cases, mass access to cheap energy was central to the take-off, mattering way more than, say, free trade. Though, as with the Asian Tigers, access to the US consumer market was central to the Japanese, and Chinese, export surges.

In the contemporary US—and across Western democracies generally—there are a whole set of elite-vetoing networks. We see elite networks vetoing cheap energy; vetoing employing people based on competence and capacity; vetoing the expression of inconvenient concerns, especially on immigration.

Commentator Douglas Murray’s acid observation applies:

0:30 Do the students on American campuses realize that, whilst they are being expensively educated into idiocy and uselessness, for each of them, there’s a dozen students in China working their socks off to get a lifestyle that these kids in America seem to think is their birthright. It ain’t their birthright. It’s not inevitable.

The centre-left political Parties are increasingly the Parties of the unaccountable classes—the classes of people paid to turn up, not for their performance: including our increasingly disastrous universities. They are the classes whose claims on authority and resources both fuel—and are fuelled by—these elite-veto networks. If you vote for centre-left Parties, you are—with very few exceptions, such as the Danish Social Democrats on immigration—voting for the entrenchment and expansion of such elite-veto networks.

You are voting for the self-righteous politics of no you can’t. For the politics of the blue-haired HR scolds. For public discourse shifted away from words as mechanisms of information and persuasion to words as control-and-status “magic spells”: uttering the right words to signal and raise one’s status; uttering the right moral abuse control words to make others do what you want; uttering the right curses to cast wrongthinkers out.

Yet, if one votes for conventional centre-right Parties, you are not voting for the lifting of those elite vetoes. On the contrary, at best you are simply not voting for their further expansion and entrenchment. Often, not even that is true.

These elite-vetoes are, to put it mildly, toxic. All the formal property rights and rule of law in the world will not save us from their effects.

Even less so when such elite vetoes are used to defy the law—as we see with “diversity hiring” in the US and pro-Trans defiance of the UK Supreme Court sex-means-biology ruling in the UK. For if you believe you and yours own morality—with all the sense of righteous authority that entails—then such constraints, legal or otherwise, are an insult to righteousness. The rule of law also rests on conventions.

But property rests on conventions of mutual acknowledgement. You don’t own morality, if others refuse to defer to your pretensions. The question then arises: why have conventional centre-right Parties within Western democracies deferred so much to these toxic vetoes?

References

Books

Douglas Allen, The Institutional Revolution: Measurement and the Economic Emergence of the Modern World, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Yoram Barzel, Economic Analysis of Property Rights, Cambridge University Press, [1989], 1997.

Christopher I. Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, 2009.

Cristina Bicchieri, The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, 2017.

Michael J. R. Crawford, An Expressive Theory of Possession, Hart Publishing, 2020.

R. H. Coase, The Firm, The Market and the Law, University of Chicago Press, 1988. Includes ‘The Nature of the Firm’ (1937) and ‘The Problem of Social Cost’ (1960).

Ronald Coase & Ning Wang, How China Became Capitalist, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Yasheng Huang, The Rise and Fall of the East: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline, Yale University Press, 2023.

Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford University Press, 2023.

Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N J Dawood, Princeton University Press, [1377] 1967.

Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Cosimo, [1921] 2005.

Dieter Kuhn, The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China, Harvard University Press, [2009] 2011.

Robert Neuworth, The Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, Pantheon Books, 2011.

Mancur Olson, Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships, Basic Books, 2000.

Jordan Peterson, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Routledge, 1999.

John P. Powelson, Centuries of Economic Endeavor: Parallel Paths in Japan and Europe and Their Contrast with the Third World, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position And How We Use It, HarperCollins, 2022.

Edward Peter Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Yuhua Wang, The Rise and Fall of Imperial China: The Social Origins of State Development, Princeton University Press, 2022.

Xueguang Zhou, The Logic of Governance in China: An Organizational Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Fei Xiaotong, From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society, trans, with an introduction and epilogue by Gary G. Hamilton and Wang Zheng, University of California Press, 1992.

Articles, essays, etc.

Plamen Akaliyski, Vivian L. Vignoles, Christian Welzel, and Michael Minkov, ‘Individualism–collectivism: Reconstructing Hofstede’s dimension of cultural differences,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (2025) Advance online publication. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2027-01517-001.html

Stephen Broadberry, ‘Accounting for the Great Divergence: Recent findings from historical national accounting.’ Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers, Number 187, March 2021. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/accounting-great-divergence-recent-findings-historical-national-accounting

Arthur L. Corbin, ‘Legal Analysis and Terminology,’ The Yale Law Journal , Vol. 29, No. 2, Dec., 1919, 163-173. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9effd79b-398b-4935-aff7-45394cde96e8/content

Harold Demsetz, ‘Towards a Theory of Property Rights’, American Economic Review, Volume 57, Issue 2, May 1967, 347-359. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/38c0/4ebc14c2f5fc70a61f4521f6568522413a92.pdf

Adam K. Frost, Zeren Li, ‘Markets under Mao: Measuring Underground Activity in the Early PRC,’ The China Quarterly, 2023, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/markets-under-mao-measuring-underground-activity-in-the-early-prc/FCED40169CCA6DEEF21B48012BC4D38C

Yegor Gaidar, ‘The Soviet Collapse: Grain and Oil,’ AEI, April 2007, 2007-09 #21440, compiled from a lecture delivered by Yegor Gaidar at AEI on November 13, 2006. https://www.scribd.com/document/428148552/Grain-and-Oil

Clifford Geertz, ‘The Bazaar Economy,’ The American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Suppl.: Papers and Proceedings of the Ninetieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association) (May, 1978), 28-32. http://hypergeertz.jku.at/GeertzTexts/Bazaar_Economy.htm

Jack A. Goldstone, ‘Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the “Rise of the West” and the Industrial Revolution,’ Journal of World History, (2002) Vol. 13, No. 2, 323-389. https://culturahistorica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/goldstone-efflorescences.pdf

F. A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society,’ American Economic Review, Sep. 1945, XXXV, No. 4, 519-30. https://statisticaleconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/the_use_of_knowledge_in_society_-_hayek.pdf

Douglas A. Irwin, ‘Adam Smith’s “Tolerable Administration Of Justice” And The Wealth Of Nations,’ Working Paper 20636, October 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20636

Monika Karmin, et al., ‘A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture,’ Genome Resources, 2015 Apr;25(4):459-66. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381518/

Meir Kohn, ‘Money, Trade, and Payments in Preindustrial Europe,’ in S. Battilossi et al. (eds.), Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, Spring, 2018. https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-981-10-0622-7_15-1

Meir Kohn, ‘An Alternative Theoretical Framework for Economics,’ Cato Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 2021). https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/alternative-theoretical-framework-economics

Stephen Kosack and Jennifer Tobin, ‘Funding Self-Sustaining Development: The Role of Aid, FDI and Government in Economic Success,’ International Organization, (2006), 60: 205-243. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4854295_Funding_Self-Sustaining_Development_The_Role_of_Aid_FDI_and_Government_in_Economic_Success

Arthur Lewis, ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour,’ The Manchester School, May 1954. https://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/368/368lewistable.pdf

Debin Ma, ‘Rock, scissors, paper: the problem of incentives and information in traditional Chinese state and the origin of Great Divergence,’ Economic History Working Papers 37569, London School of Economics and Political Science, Department of Economic History, 2011. https://www.lse.ac.uk/Economic-History/Assets/Documents/WorkingPapers/Economic-History/2011/WP152.pdf

Debin Ma & Jared Rubin, ‘The Paradox of Power: Principal-agent problems and administrative capacity in Imperial China (and other absolutist regimes),’ Journal of Comparative Economics, (2019), 47(2), 277-294. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/esi_working_papers/212/

Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Laurent Weill, ‘Is corruption an efficient grease?,’ BOFIT Discussion Papers, (2008) No. 20/2008, Bank of Finland, Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT), Helsinki. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/212633/1/bofit-dp2008-020.pdf

Nathan Nunn, ‘Culture And The Historical Process,’ NBER Working Paper 17869, February 2012. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17869

Yingyi Qian, ‘How Reform Worked in China,’ William Davidson Working Paper, Number 473, June 2002. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=317460

Harold Robertson, ‘Complex Systems Won’t Survive the Competence Crisis,’ Palladium: Governance Futurism, June 1, 2023. https://www.palladiummag.com/2023/06/01/complex-systems-wont-survive-the-competence-crisis/

Michael T. Rock, Heidi Bonnett, ‘The Comparative Politics of Corruption: Accounting for the East Asian Paradox in Empirical Studies of Corruption, Growth and Investment,’ World Development, Volume 32, Issue 6, 2004, 999-1017. https://afca.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Rock-Bonnett-2004-The-comparative-politics-of-corruption-Accounting-for-the-East-Asian-paradox-in-empirical-studies-of-corruption-1.pdf

Dani Rodrik, ‘Feasible Globalizations,’ NBER Working Paper, 9129, September 2002. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9129

Safeguard Defenders, 110 Overseas: Chinese Transnational Policing Gone Wild, October 29, 2022. https://safeguarddefenders.com/sites/default/files/pdf/110 Overseas (v5).pdf

Daniel Seligson and Anne E. C. McCants, ‘Coevolving institutions and the paradox of informal constraints,’ Journal of Institutional Economics, 2021, 1–20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/CE95D185B7EA557C5D0066FA7D785BCB/S1744137420000600a.pdf/div-class-title-coevolving-institutions-and-the-paradox-of-informal-constraints-div.pdf

Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘Size and dynastic decline: The principal-agent problem in late imperial China, 1700–1850,’ Explorations in Economic History, Volume 54, 2014, 107-127. https://conference.nber.org/confer/2011/CE11/Sng.pdf

David Sun, ‘Arctic instincts? The Late Pleistocene Arctic origins of East Asian psychology,’ Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, Online First Publication, March 3, 2025. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2025-88410-001.html

Jordan E. Theriault, Liane Young, Lisa Feldman Barrett, ‘The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure’, Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 36, March 2021, 100-136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32008953/

Chenggang Xu, ‘The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development’, Journal of Economic Literature, 2011, 49:4, 1076–1151. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227363166_The_Fundamental_Institutions_of_China’s_Reforms_and_Development

Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw, & Marcus W. Feldman, “Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck”, Nature Communications, 2018, 9:2077. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04375-6

Yes, there are surely political considerations also, nevertheless the sackings and prosecutions are presented as corruption cases. Both are aggravated by the lack of checks and balances in the system.

The internally-evolved political structure of Somaliland is something of a standing rebuke of the US attempt to clone itself in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"When looking at the apparently astonishing levels of welfare fraud in Minnesota, the Somalis involved were just acting like, well, Somalis—people from a highly clannish and collectivist culture who sharply differentiate between in-group and out-group. There is a reason there is such a striking correlation (0.91) between how collectivist a culture is and how corrupt the state is." Realisation of this appears to be gaining ground - for example in our grooming gangs - Pakistani muslims just acting like Pakistani muslims.

> When looking at the apparently astonishing levels of welfare fraud in Minnesota, the Somalis involved were just acting like, well, Somalis

It's not just that. Somalia itself now runs on a similar principle wrt foreign aid.

https://freemarketsandfirepower.substack.com/p/anarchy-state-and-somalia